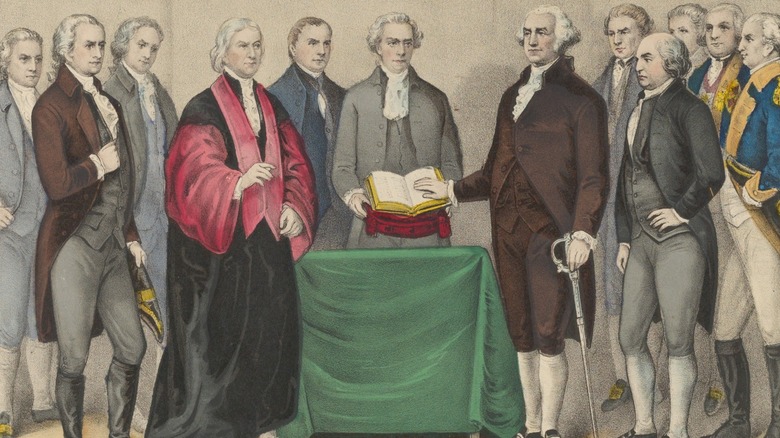

The 14 Men Who Were President Before George Washington

Who was the first president of the United States? Easy question — George Washington, of course. But it turns out, not everyone agrees with that statement. Before Washington, 14 different men led the United States' earliest governmental bodies and also bore the title of president. As early as 1774, the leaders of the American Revolution had established the Continental Congress to direct their efforts against Great Britain, even before they had decided to form their own country. The Continental Congress, in its first and second iterations, continued to meet until 1781. With the ratification of the Articles of Confederation, an early form of a constitution, the Confederation Congress replaced the Continental Congress.

The presidents of these two congresses didn't have the same powers or duties as the president of the U.S. They had no control over the actions of the 13 colonies. They were elected by other members of the congress, not by citizens, and their main job was to preside over congressional sessions. They were also in charge of welcoming visitors and writing letters on the congress' behalf. Because of the timeline of the establishment of the Articles of Confederation and the first use of the term "United States," various presidents of the congresses are sometimes considered to be the first U.S. presidents.

Peyton Randolph

The very first president of the Continental Congress was elected unanimously — Peyton Randolph of Virginia — in 1774. Thomas Lynch, who nominated him, described him as "having great Dignity," according to a entry in John Adam's diary. Randolph also had some serious connections: He was a good friend of George Washington and the first cousin once removed of Thomas Jefferson. Interestingly, Jefferson probably didn't consider Randolph fit for leadership, saying, "He was indeed a most excellent man [but] heavy and inert in body, he was rather too indolent and careless for business" (via Constitution Center). Jefferson later said, though, that "no man commanded more attention" (via The Thomas Jefferson Papers at the Library of Congress).

Randolph was also an important addition to the congress because of his reputation as a political moderate. Prior to his congressional service, Randolph was a lawyer and attorney general of Virginia. He served in the Continental Congress three times between 1774 and 1775 and was its president twice. He died in Philadelphia the night after a congressional meeting. The other members of the congress paused from meeting to show their respect at his funeral.

Henry Middleton

Like Randolph, the Continental Congress' second president wasn't particularly radical: he belonged to South Carolina's unofficial aristocracy. Henry Middleton was a planter with vast land holdings and around 800 slaves, according to South Carolina Encyclopedia. He was supposedly rich enough to pay for an entire revolutionary regiment (via Dictionary of American Biography). He married three times, gaining land and political connections through each marriage. His third wife — who he married during the Revolution — was the daughter of a Scottish earl. Her goddaughter described Mary Mackenzie Middleton as a practical person: "not handsome but elegant, very clever and shrewd, a staunch friend and a capital woman of business" (via Middleton Place).

Middleton was president of the Continental Congress for less than a month in 1774. His singular act of signing congress' "Declaration of Rights and Grievances," in response to the so-called Intolerable Acts passed by Britain earlier that year, set forth the idea that American colonists were equal to any other British citizen and should not be taxed without parliamentary representation.

Afterward, however, Middleton resigned from the congress because he opposed declaring independence. When the British captured Charleston, S.C., he claimed their protection. However, he wasn't punished by the U.S. government after the war, probably because of his contributions to the revolutionary movement. Middleton's home is now a museum hosting events, including some Revolutionary War reenactments, according to The Post & Courier.

John Hancock

John Hancock is better known for his famous signature than for being president of the Continental Congress, but in fact, the two things are related. Hancock was president of the congress at the time the Declaration of Independence was written and signed. The earliest copy of it only includes his name and that of the congressional secretary, Charles Thomson. Signing it was part of his duty as the president — and also an incredibly dangerous, treasonous act.

Before the revolution, Hancock was a politician and merchant, and his rebellious tendencies probably began when British officials impounded one of his boats in Boston Harbor, claiming he hadn't paid taxes on his cargo, and thus making him a wanted man for alleged smuggling. Before the Continental Congress, he was president of the Massachusetts Provincial Congress. He also fought in the war and later became governor of Massachusetts.

Hancock is widely recognized as the first signer of the more famous copy of the document, which includes 56 signatures. Supposedly, when he signed, he said, "There, John Bull can read my name without spectacles, he may double his reward, and I put his at defiance" (via National Archives). John Bull was a fictional representation of England. In other versions of the story, Hancock wanted the king to be able to read his signature.

Henry Laurens

Henry Laurens may be better known these days as the father of "Hamilton" hero John Laurens. He was, however, just as prominent a member of the revolution as his son. Like Henry Middleton, he was from Charleston, South Carolina, a planter, and a slave owner. His import-export business became so successful, he expanded into slave trading. Initially he appeared to be a moderate when it came to revolution — instead of supporting protests of the Stamp Act and more violent actions, Henry encouraged more passive resistance. However, this attitude didn't stop him from being critical of British interference in the colonial economy. As a merchant, he stood to lose.

Henry was Continental Congress president in 1777 and later became ambassador to Holland in 1779. On his way there to negotiate an alliance, he was captured by the British. According to his papers (via the Journal of the American Revolution), he tried to dispose of important documents before capture, but the British found some anyway, one of which led them to declare war on Holland. Henry Laurens was thrown into the infamous Tower of London and stayed there for more than a year, under severe conditions, until the U.S. traded Lord Cornwallis, a British general in the war, for his release. Ironically, Cornwallis was John Laurens' prisoner, after Cornwallis had surrendered at Yorktown.

While in the Tower, an old friend offered Laurens a pardon if he would admit fighting for the rebels was wrong. Laurens declined, saying, "I am afraid of no consequences but such as would flow from Dishonorable Acts," as per his papers (via the Journal of the American Revolution).

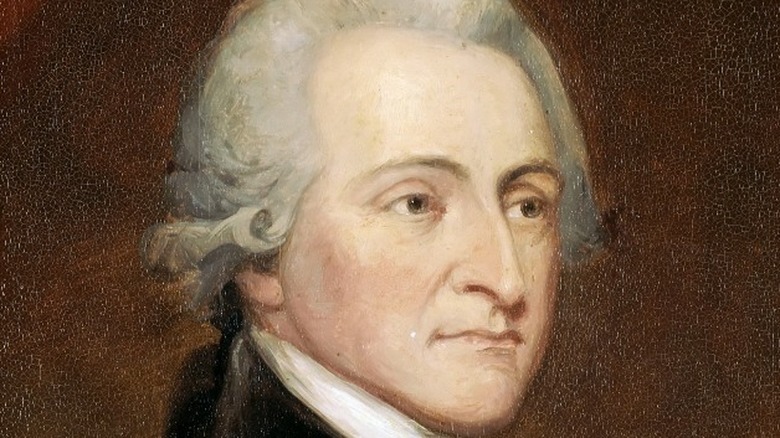

John Jay

John Jay has other claims to fame besides his Continental Congress presidency — namely, being the first chief justice of the U.S. Supreme Court. He chose that over any other position in George Washington's cabinet — Columbia University notes that Washington reportedly offered him his pick before anyone else. Jay held an impressive array of offices during his political career. He also helped negotiate two major treaties — the Treaty of Paris that expanded American territory and the Jay Treaty, which established peace with Great Britain. He wrote some of the Federalist Papers, explaining and defending the U.S. Constitution. In them, he warned against foreign influence and lack of national unity, saying "a band of brethren, united to each other by the strongest ties, should never be split into a number of unsocial, jealous, and alien sovereignties" (via Library of Congress).

John Adams said Jay was "of more importance than any of the rest of us" (via PBS), referring to the nation's founders. However, he's less well known than many, which PBS attributes to his quiet personality and absence at important moments like the signing of the Declaration of Independence. Despite his retiring nature, Jay also established the first counterintelligence agency in America in 1776, notes the CIA, with New York's Committee for Detecting and Defeating Conspiracies. It was a combination of politicians and militia men, and its doings were top-secret. They even foiled an assassination plot against Washington. Compared to all that, his stint as Continental Congress president was relatively uneventful.

Samuel Huntington

Samuel Huntington is one of the men sometimes called the first U.S. president. In fact, NPR interviewed the president of the Norwich Historical Society in Connecticut, which in the aughts was working to get him recognized as one of the first leaders of the country. The society contends that, because he held the position when the Articles of Confederation were established in 1781, and that document contained the first written reference to the United States, he deserves the title as the first instead of George Washington. In his hometown of Norwich, Connecticut, the historical society president campaigned to raise $10 million to build a presidential library for Huntington -– even though he admitted not many documents or artifacts have survived to put in it.

Huntington was a member of the revolutionary congresses for eight years and president for two. He held multiple political positions in Norwich before the war and afterward was the state's first governor and chief justice of its Supreme Court. One of the tensest moments of his governorship was Shays' Rebellion, an uprising over the post-war economy. The governor of Massachusetts wrote Huntington asking for help suppressing it, and Huntington replied that he'd send soldiers. In his response, Huntington offered assurances that Connecticut would remain stalwart: "I am happy to acquaint your Excellency that there is reason to expect good order & Government will be Supported in this State, & the disaffected in Massachusetts will derive no aid or Support from this quarter" (via Maine Historical Society).

Thomas McKean

Thomas McKean is unusual, because he held office in two states at once. He was one of the new state of Delaware's delegates to the Continental Congress while also chief justice of the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania. McKean went back and forth in many aspects of life, including switching political parties multiple times, which made him a divisive figure in Pennsylvania. Nonetheless, he later became the state's governor. He also briefly acted as president of Delaware — the equivalent of governor — when its president was captured during the war. McKean also signed the Declaration of Independence, although according to G.S. Rowe in "Thomas McKean: The Shaping of an American Republicanism," McKean couldn't actually remember when he signed the important document.

In the midst of all this, he also served in the war and wrote letters back to his wife about the harrowing experience. To him, the British soldiers on the other side were "Enemies of Mankind." His service was short-lived; he wrote his wife that he "wish[ed] to be rid of all public employments."

Nonetheless, he went back to the Continental Congress. He was its president when the British surrendered at Yorktown, effectively ending the American Revolution. After the war, he was a proponent of a strong judiciary and of the concept of judicial review, meaning the U.S. Supreme Court could determine whether or not a law was constitutional.

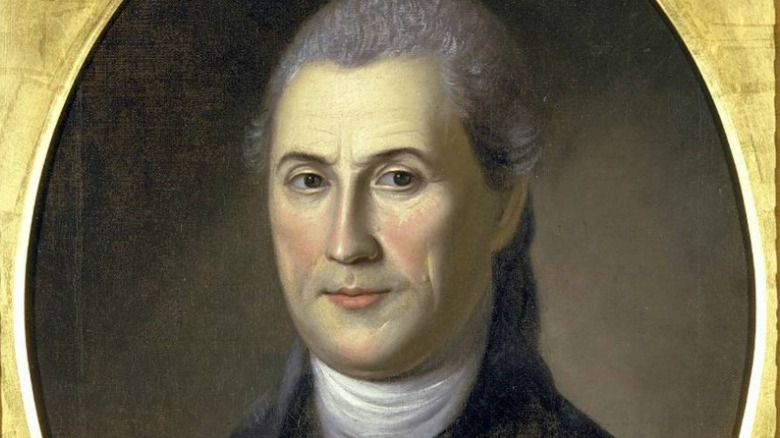

John Hanson

John Hanson is also sometimes considered the first president of the United States. As the first president of the Confederation Congress, he was the first to act under the laws of the Articles of Confederation, a precursor to the U.S. Constitution. However, at this point, the president was still part of the legislature, not an independent position. It wouldn't be separate until the Constitution was ratified in 1789, about nine years after Hanson's tenure as president ended. Hanson's position, and that of other Confederation presidents, was more like the British prime minister's job.

Hanson was part of Maryland's revolutionary government, which wrested state control from the British. In June 1776, Maryland was reluctant to declare independence, so Hanson brought forward resolutions for independence and gave an impassioned speech to the Maryland Convention about why the "resolutions ought to be passed and it is high time" (via "Remembering John Hanson," by Peter H. Michael). He turned the tide: The resolutions were passed a week later. Maryland was the last state to consent to independence.

Hanson died in 1783, only about a year after his presidency ended. His obituary in the Maryland Journal described him as "a servant to his country in a variety of employments" (via "Charles County Gentry").

Elias Boudinot

Elias Boudinot, ninth president of the American congresses, was from Philadelphia. He later served as the director of the city's national mint from 1795-1805. However, in the Continental Congress, he represented New Jersey. He was also a member of the U.S. House of Representatives for six years.

Boudinot was an ardent Christian. He wrote and published "The Age of Revelation" to demonstrate his opposition to the writings of Thomas Paine, whom he called an "infidel author." Boudinot felt the need to defend his faith in light of Paine's anti-Christian arguments. Interestingly, in this work, Boudinot also stated his belief that laws should be elastic. He wrote, "There is no other instance (than that of the Mosaic code [Ten Commandments]) of a body of laws being produced at once, and remaining without addition afterwards."

Late in life, Boudinot was also president of the American Bible Society, which is what brought him into contact with the young Cherokee leader Gallegina. Highly impressed with Boudinot, Gallegina took Boudinot's name from then on.

Thomas Mifflin

Thomas Mifflin's early revolutionary career was marked by a scandal. In 1775, he became one of George Washington's aides and was quickly promoted to quartermaster general. In this position, he made sure soldiers received their uniforms and equipment. Richard Henry Lee, another future congress president, wrote to Washington, "I think you could not possible have appointed a better Man to his present Office" (via National Archives).

Mifflin was rapidly promoted in rank. However, he mismanaged the Quartermaster Department financially. Worse still: He plotted to replace Washington with Horatio Gates as commander of the troops. He was eventually investigated for misconduct and had to resign in 1779.

None of that prevented Mifflin from serving in the Confederation Congress or being elected its president in late 1783. Ironically, in this role, he accepted Washington's resignation as commander when the war was ending. He also oversaw the ratification of the Treaty of Paris, which established peace between the U.S. and Britain. He would go on to be Pennsylvania's first governor.

Richard Henry Lee

Richard Henry Lee was a member of one of Virginia's most powerful families (it eventually produced Robert E. Lee too). Richard Henry Lee and his brother Francis Lee held many different political positions in the state. Before the war, they made waves (and enemies) in the House of Burgesses.

Later, they did the same in the Continental Congress. Allied with John and Samuel Adams, they clashed with Silas Deane of Connecticut, whom they believed to be using political clout to advance his business interests. Richard Lee wrote to then-president Henry Laurens, "there is so much rottenness at the bottom and in every part of their System," referring to Deane and his party (via University of South Carolina). He asked they be investigated. The feud and resulting divisions in the congress led to both Laurens and Richard Lee resigning.

Before all that, though, it was Richard who proposed the resolution to separate from Great Britain, declaring to the Continental Congress "that these united colonies are and of right ought to be free and independent states" (via National Archives). Years later, he joined the Confederation Congress and became its president from November 1784 to November 1785. He left public service definitively in 1792 because of poor health.

Nathaniel Gorham

Nathaniel Gorham started turning heads during the revolution because of his work on Massachusetts' Board of War, helping defend the state's coast and supporting military expeditions into Canada. This earned him a place as a delegate to the Confederation Congress, where he rose to the presidential position.

Having contributed to the writing of Massachusetts' constitution, he was appointed to the national Constitutional Convention where he advocated for a strong central government. He wrote to James Madison in 1789: "It appears to me that one of the greatest mistakes the old Government ever made was the frequent applications to States and in some instances when there was no real necessity for it; the Congress itself having sufficent power in the case — the consequence was that at length they became afraid to use some of their Constitutional Powers" (via National Archives).

Gorham was congressional president during Shays' Rebellion and had seen how helpless the national government was, relying on state militias to crush it. He thought things would only get worse without a strong executive. That's why he proposed making the king of Prussia king of the Americas as well — unsurprisingly, not a popular or successful plan. He was nonetheless optimistic about George Washington as a leader, writing to him that his presidency "may be an event conducive to the wellfare of the People and of happiness and honor to yourself is my most earnest wish" (via National Archives).

Arthur St. Clair

Like Thomas Mifflin, Arthur St. Clair was one of George Washington's aides during the Revolutionary War and eventually became a major general. According to Mount Vernon's website, Washington was a big fan after St. Clair's advice led him to win a battle at Princeton, New Jersey. However, St. Clair made a lot of military blunders later on and ended up on trial for them multiple times, including when he lost Fort Ticonderoga, a strategic location that American forces had captured in the early days of the war. St. Clair was court-martialed for abandoning the fort, but Washington still defended him.

St. Clair was the Confederation Congress' president in 1787, after which the congress named him governor of the Northwest Territory. In that capacity, he tried to remove Native Americans from the area, which led to a major military defeat where he lost more than 900 men. According to Col. Tobias Lear, St. Clair had definitively lost Washington's good opinion at that point, with Washington saying, "He's worse than a murderer ... the blood of the slain is upon him" (via "Washington in Domestic Life," by Richard Rush).

When an inquiry began into the campaign, St. Clair protested to Washington: "I am not conscious that any thing within my power to have produced a more happy Issue, was neglected" (via National Archives). Washington was kinder in his reply than when speaking to Lear, saying St. Clair's "desire of rectifying any errors of the public opinion ... [was] "highly laudable" (via National Archives).

However, despite defending his actions and being exonerated, St. Clair resigned at Washington's request. Surprsingly though, he stayed governor of the territory.

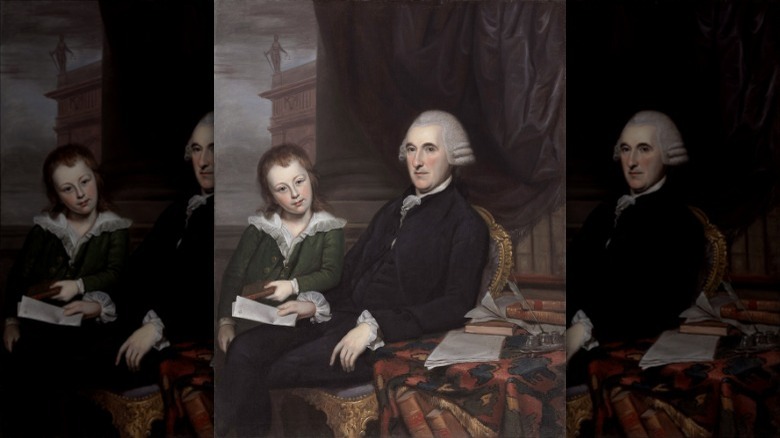

Cyrus Griffin

Cyrus Griffin was the last president of the Confederation Congress before the Articles of Confederation were replaced by the American Constitution, but he wasn't originally in favor of American independence. In 1775, he wrote a "plan of reconciliation" for Britain and the colonies, explaining to the colonial British secretary of state, the Earl of Dartmouth, "I am convinced that a plan of this sort is the only way to bring about a happy and permanent accommodation" and decrying what he considered a disaster for the country (via The Journal of Southern History). However, by 1778, Griffin was a member of the Continental Congress. He left it in 1780 to become a judge but returned and became president about eight years later.

One of the most interesting episodes of Griffin's life had nothing to do with politics. While studying law at the University of Edinburgh, he met the daughter of a Scottish earl and eloped with her. When he returned to England a few years later, it wasn't to deliver his proposal to Dartmouth — it was to make sure he got his fair share of the earl's inheritance, notes the Washington and Lee Law Review.