How America's Pharmaceutical Industry Got Out Of Control

For decades, Americans have faced a worsening healthcare crisis; costs for prescription drugs keep rising. Price hikes in a given year can be anywhere from 6 to 5,000 percent, well beyond the rate of inflation, leaving patients with hefty drug bills regardless of insurance coverage. It's a situation that has defied multiple presidential administrations' promises of relief, and left millions of Americans stressed and vulnerable to losing sometimes life-saving medication.

The pharmaceutical industry has maintained over the years that its price hikes are a necessity, lest funding for research into new drugs and cures dry up. They've also pointed to the rebates, coupons, and discounts they offer patients and insurance providers. But these arguments have been difficult for many to accept, not least because America's spiraling drug prices are not seen elsewhere in the developed world. The same drugs, made by the same companies, cost less — sometimes far less — in other countries.

The Asheville Citizen Times described the U.S. pharmaceutical industry, when compared to peer nations, as being in a select unregulated club. While not completely true — there is the FDA, after all — drug companies in America have long enjoyed less oversight of their business practices, and no real controls on how they price their products, all at consumers' expense. And, through lobbying and loopholes in existing law, this lack of oversight has persisted. How did we get here? Here's how America's pharmaceutical industry got out of control.

The pharmaceutical industry skews research

A standard line by the U.S. pharmaceutical industry — that price hikes are needed to fund research into new drugs — runs up against the fact that the federal government subsidizes a large portion of pharmaceutical research. Besides offering tax credits to drug companies and other industries that conduct research and development since 1981, the lion's share of basic research used by such companies is done through public institutions. According to the Los Angeles Times, while publicly funded research has led to innovations, drug companies have long prioritized developing minor variants on existing medications. Their funds are more often directed towards sales and to financial practices meant to boost payouts to shareholders.

Drug companies also invest in education. For decades, it has poured hundreds of millions of dollars into funding opportunities for medical students. But some studies have found that a significant amount of this money has gone into entertainment, luxury, and other enticements rather than on anything directly pertaining to education. Some observers have said that such funding amounts to promotion of the drug companies to those who would be prescribing their products, and a compromising influence on educational institutions. Some schools have moved to reduce their reliance on commercial funding, and others have advocated for reforms to the way companies can make donations. Dr. Murray Kopelow of the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education suggested putting such contributions into a blind trust (via the BMJ).

Drug companies lobby doctors to prescribe their drugs

Many drugs developed by pharmaceutical companies are only available to customers through a doctor's prescription. To boost sales, these companies have long targeted doctors through sales representatives, who frequent doctors' offices carrying slick pitches and free samples of the latest pharmaceuticals. These free samples can then be offered to patients and, if effective or popular, lead to paid prescriptions. Up until 2002 (per DrugWatch), it was also routine for sales reps to socialize with doctors away from work and offer them gifts and entertainment, sometimes on a grand scale.

Studies have shown that, contrary to the claims of doctors and drug companies, this kind of aggressive lobbying has influenced which drugs are added to hospital formularies and which are prescribed by doctors. At times, this has led to unsafe medications going out to vulnerable patients. In 2005, sales reps for Merck & Co pushed arthritis drug Vioxx on doctors, leaving out of their pitch the fact that it significantly increased the risk of a heart attack (per The Washington Post).

Besides lobbying doctors to a point some have called bribery, drug companies have also courted doctors to endorse their products. TV commercials and live panels for other physicians regularly feature paid spokespeople, current or former practitioners, touting the benefits of a company's drugs. These jobs pay well, but the talking points are dictated by the industry, and the doctors hired are not always qualified or credentialed.

The U.S. has no drug price regulation

When critics of the U.S. pharmaceutical industry describe it as unregulated, they are often specifically referring to drug price regulations. In most of the developed world, governments have agencies that directly negotiate with pharmaceutical companies to determine which drugs come onto market, and what their price will be. How different a new product is from existing drugs, any improvement in treatment offered, potential risks, and just how much a country is prepared to pay are all factored into the decision.

In the United States, any drug that passes safety checks can go on the market, and pharmaceutical companies can charge whatever they'd like for it. Negotiations on price are done by private insurance policies, and because of the fragmented nature of the American health system, no one entity has much in the way of power to check a drug company if they decide they want to hike prices. Thus, a prescription for Humira, which cost $822 in Switzerland as of 2018, cost $2,669 in America, despite there being no difference in the drug by region (per Vox).

Drug companies have said that the high costs in the U.S. fuel research, and accuse the rest of the world of reaping the benefits. And treating the U.S. drug market as a utility, as some have called for, might mean some reduction of choice and innovation. But studies have found that regulated markets still make major contributions to research.

Pharmaceutical firms spend more on marketing than on research

While pharmaceutical companies do put some of their profits into research and development, the real investments are made in marketing. Billions of dollars are spent every year on ad campaigns designed to get doctors and customers interested in the latest drugs, and the amount spent keeps rising. A 2019 study published by JAMA found that, between 1997 and 2016, marketing expenditures increased by $12.2 billion, with a hefty percentage of that spent targeting doctors. In the same time frame, the number of TV commercials promoting drugs to average viewers went from 72,000 to 663,000. And the money poured into sales and marketing can be deducted by pharmaceutical firms come tax season.

The design of some ad campaigns has also been suspect. Between 2014 and 2015, the U.S. Senate Committee on Finance investigated Gilead Sciences, Inc. The company had put out a drug to treat hepatitis C, Sovaldi, at $1,000 per pill, and followed it up with a similar drug, Harvoni, at an even greater price. That represented a $5 billion cost to Medicare and Medicaid and spiked their spending on hepatitis treatments. The Senate investigation found that Gilead Sciences had rolled out Sovaldi with an eye to profit above all else, and its marketing campaign was designed with the aim of setting a high bar for another, more expensive drug to clear.

The patent system is abused to keep control of certain drugs

If a drug from one pharmaceutical company is too expensive, why not buy a competitor's version? As it happens, many drugs are monopolized by the company that developed them or bought control of them, thanks to the U.S. patent system. Providing exclusive rights and legal protection to the inventor or creator of something goes back to antiquity, and the modern patent system was designed to encourage innovation into pressing societal problems. But that window of exclusivity was meant to be short; after a given time, inventions and products should become widely available for others to use.

The length of a patent is 20 years, which comes to seven to 12 years for a drug after it clears the approval process. Many drug companies work to extend the life of their patents through loopholes. One trick to that end is called evergreening, where a company makes a small change — sometimes as superficial as the drug's appearance — and gets a new patent on the modified drug. Another practice, thicketing, involves flooding the system with patent applications and legal battles such that the entire process becomes frozen (per USA Today).

Lobbying by pharmaceutical firms to keep imported drugs illegal and public bodies from negotiating prices work with patent abuse to keep drug prices high. And when patents do expire, and generic versions of a drug begin to appear, even that can't always bring down prices: Larger companies simply buy the competition.

The drug industry's lobbying efforts are record breaking

One of the chief reasons the issues with the American pharmaceutical industry have persisted is the amount of influence wielded by that industry in Washington. For decades, drug companies have poured hundreds of millions of dollars every year into lobbying politicians. These campaigns aren't just expensive; they're record-breaking. An investigation by the Center for Public Integrity in 2005 found that the pharmaceutical lobby outspent all other industries (per The Center for Public Integrity), a situation that was still the case in 2021.

A large chunk of the industry's political spending is spent on lobbyists who interact directly with federal and state authorities. But drug companies also spend handsomely on campaign contributions to candidates running for office. Both political parties and both houses of Congress have benefitted from such spending. Between these efforts, drug companies have been able to sway major pieces of legislation affecting their business, either by killing or watering down new regulations, or carving out lucrative provisions and loopholes. Politicians who don't play ball face attack ads.

For all their efforts, drug companies haven't prevented all attempts at reform. The industry's lobbying kicked into overtime throughout 2021 and 2022, as the Democratic-controlled Congress sought to push through a massive bill that would, among other things, introduce some price controls on select prescription drugs. In the end, $142 million worth of lobbying couldn't stop the Inflation Reduction Act, and its provision for limited price controls, from becoming law in late 2022 (per Reuters).

Officials and shareholders from drug companies get government jobs

Drug companies are part of the issue of the revolving door — the movement of statesmen and government employees into private business and vice versa — as much as any industry. Many of the lobbyists that pharmaceutical firms send to Washington are former government workers. Former employees of the Food and Drug Administration, the agency tasked with regulating drug companies, make up a conspicuously large number of hires by the businesses they supervised. The salaries are tempting, not only for rank and file bureaucrats, but for elected officials who've alienated voters.

While some have maintained that government workers going to work in the industries they once regulated has a benefit — they know the requirements that new products need to meet and can ensure all due research has been conducted — it's led to questions of a conflict of interest. "If you know in the back of your mind that your career goal may be to someday work on the other side of the table, I wonder whether that changes the way you regulate," Dr. Vinay Prasad told NPR.

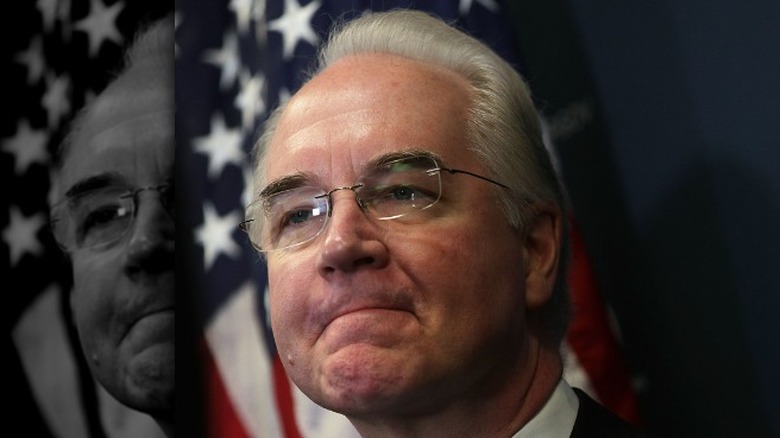

The revolving door swings the other way too; former employees of drug companies, or individuals with a large financial stake in the industry, make it into government. Tom Price, health secretary for the Trump administration, bought $90,000 worth of drug stock while still in Congress, just before he lobbied the Australian government on the industry's behalf (per Pro Publica).

The cost of drugs has no relation to their value

If it's going to cost an arm and a leg to treat the pain in your arms and legs, a drug might as well provide excellent treatment. But paying more for a drug doesn't mean you're getting access to better medicine. Studies that have looked for a relationship between the U.S. price of a drug and its benefits haven't found any.

Some countries practice what's called a value-based pricing scheme, where the cost of a drug is partially determined by the value it provides to patients who use it. Using such a system here, one study found, would bring down the price of most drugs (via the Los Angeles Times). The industry response, as it has been to many lines of complaint about their prices, is to say that the money spent by customers fuels the innovation of new treatments. But prices in America are as divorced from development needs as they are from value.

Besides putting many drugs beyond the reach of those who need them, the disconnect between expense and value can erode public confidence in the quality of their medicine. Proposals to rectify the situation include having the U.S. empower agencies to negotiate drug costs using international reference pricing. Since other countries use value-based pricing, this would affect the reference price and introduce value into American prices (via Brookings).

Some Americans go abroad to get needed medication

With drug prices elsewhere in the world so much lower than those in the United States, it's not surprising that many Americans have turned abroad for their medications. Importing prescriptions from beyond the American border is illegal, but with drugs often being moved via small and inconspicuous packaging, it's difficult to enforce the laws against it. And the internet has made it easier than ever for Americans to order prescriptions through online pharmacies. The risk of fraud or poor quality control when shopping for drugs online is real, but not impossible to manage. And Americans can, and have, traveled to other countries for direct purchases.

The savings can be enormous. NPR reported on a woman who spent ten years crossing the Mexican border to find affordable drugs for her blood pressure and diabetes. A three-month supply there cost her $40. Without insurance, a one-month supply was $120 in her home state of Louisiana. But if costs for drugs are prohibitive for many Americans, so is the cost of international travel. And even for those who can afford to make the trips, being physically present isn't a sure check against quality issues, as some countries have lower safety standards for medication than the U.S.

Many Americans ration their drugs, against doctors' orders

The exorbitant cost of most drugs in the United States isn't just an inconvenience. For millions of Americans, it makes life-saving medications unaffordable, forcing them to make difficult and sometimes dangerous choices in how they manage their health. GoodRX, a regular discount provider, found that over 20 percent of Americans took on more debt or even declared bankruptcy because of how much their prescriptions cost. Over a third struggled to meet their medical bills because of drug prices, and an even larger percentage met that struggle by either finding cheaper medication, skipping doses of their medications, or rationing their supply.

The rationing of insulin has attracted headlines in recent years. Despite being nearly a century old, its cost in the U.S. has risen dramatically since the 1990s, even as prices have remained stable elsewhere in the developed world. Many patients can't afford to take insulin as prescribed, so have resorted to taking less than the prescribed dosage to stretch what they have as long as possible. Taking insufficient amounts of insulin can be fatal: Antroinette Worsham testified to the House Committee on Reform and Oversight in 2019 that her daughter started rationing after losing her job, and died at the age of 22. When not fatal, insulin rationing can still lead to neuropathy and cost sufferers their feet.