Why Escaping North Korea Is So Difficult And Dangerous

When it comes to listing the most closed-off countries in the world, one nation easily tops the list. North Korea, also known as the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (DPRK), occupies the northern half of the Korean Peninsula. It more or less officially came into being in 1948, after World War II transitioned into the Cold War. Kim Il-sung, backed by the Soviet Union, emerged as the first leader of the nation and began a powerful cult of personality that grew to include his family. The title of Supreme Leader has since passed onto his son, Kim Jong-il, followed by his grandson and current leader, Kim Jong-un.

In a generations-long effort to hold onto power, the Kim family and their loyalists have constructed one of the most authoritarian governments in modern history. Their hold on the nation and its people means that North Koreans have little to no contact with the outside world and often come up against significant issues like widespread malnutrition and a near-complete lack of freedom of expression.

Despite all that control, some North Koreans still decide it's time to leave. Maybe they watch a South Korean show smuggled into the DPRK on a thumb drive. Maybe, overworked and hungry, they hear that economic opportunity awaits beyond the border. Regardless of why it happens, the journey out of North Korea is not easy. Here's what makes defecting from this nation so difficult and dangerous.

The DMZ is treacherous

Of the North Koreans who defect to the south, only a very few attempt to escape through the demilitarized zone (DMZ) between the two nations. Looking at a satellite image of the DMZ, you may wonder why so few choose to make this particular passage. Though it spans the Korean Peninsula, it's only about 2.4 miles wide, making for a far shorter journey than what faces anyone who leaves through China.

Zoom in, however, and you'll soon notice the heavily armed guards on either side of the border. On the North Korean side, the fence is bristling with barbed wire and is even electrified in some sections. The DMZ is also believed to contain over one million landmines left from the Korean War, making every step a risk even when the razor wire is behind you and bullets aren't whizzing overhead.

Of the small number who have managed the crossing, many report that their journey, though short, was terrifying. Speaking to ABC News, former soldier Kim Kang Yoo recalled that his September 2016 flight across the DMZ took hours of navigating a valley, nearly plummeting off a cliff, digging his way beneath North Korean fences, and clambering over South Korean barriers topped with barbed wire. At one point, he said that he was so depleted and hopeless that he considered eating the rat poison he had brought with him.

Anyone who is caught faces harsh punishment

For potential defectors, the threat of being caught surely looms large in their minds. In 2018, defector Scott Kim told Business Insider that he and his mother were returned to North Korea by China after the pair had been living as undocumented workers for about a year. Kim was transported to a detention center, where he was crammed into a cell with 20 other detainees and a single toilet. They suffered regular beatings and were routinely forced to crawl instead of walk. Yet this turned out to be relatively humane, as Kim convinced guards he was a teenager and gained passage to a medical facility. If they had known he was older, Kim may have been sent to a labor camp — where he eventually went after a second escape attempt.

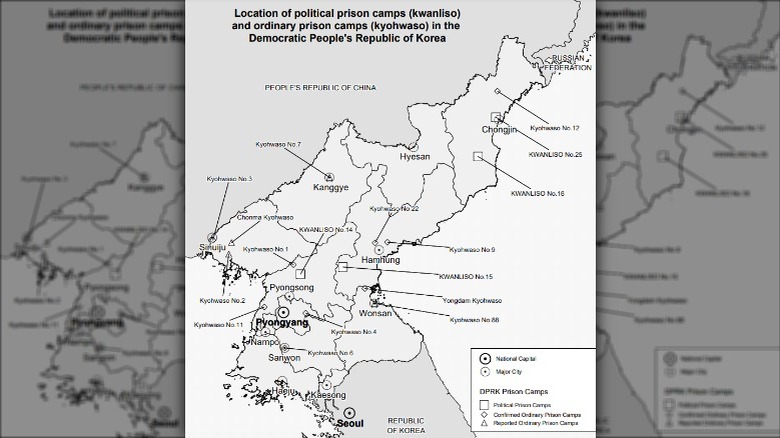

After he was caught a third time, Kim was sent to a facility for political prisoners. These prison camps are believed to be especially brutal, with interminable sentences that can subject detainees to torture, starvation, sexual assault, and forced labor.

Other attempted escapees may face more final punishment. Speaking to ABC News, defector and former North Korean border guard An Chan-il said that he witnessed a fellow soldier shot to death after an escape attempt. An obtained the man's badge and carried it with him on his own successful escape through the DMZ, saying that he hoped something of the man would still make it to the south.

Defecting can run up a hefty bill

Many defectors rely on middlemen commonly known as brokers, who accept payment to ferry people from North Korea's northern border, through China. Many then travel further south to countries like Vietnam and Cambodia, where they can take a flight to South Korea. As defector Um Yae-run told Al Jazeera in 2018, working with brokers doesn't come cheap. Border guards must be bribed, transportation must be arranged, and all is made easier with deep pockets. Um reported that her crossing in 2009 — which included darting across an iced-over river while guards shot at her — cost about $2,800. Nearly 10 years later, she estimated that people crossing the border would need to pony up more than triple that amount, at about $9,300. Anyone with their sights set on South Korea would need to bump that figure up even higher, to an estimated $14,000.

Since then, COVID lockdowns and increased border security have made the crossing all the more difficult and expensive. Because brokers now reportedly face extended prison sentences if caught, their percentages have risen. Defector Hong Gang-chul, a former border guard, told Voice of America that brokers once took a 30% commission out of money sent from defectors to family members left in North Korea. Now, it's more like 50% or even 70% in some cases. As for the cost of leaving, Hong claimed that the overall price for an escape to South Korea cost about $21,000 in 2021.

Female defectors might be trafficked

With no travel documents and oftentimes little money, female defectors are in an especially vulnerable position. Speaking to the BBC, "Mira" said that, though she came from a well-off family, she didn't have all the money needed to pay a broker up-front. Instead, she agreed to work off her debt, assuming that she would find employment in a restaurant. Instead, she was taken to an apartment and pressured to perform sexual acts in front of a webcam.

Along with eight other women, Mira was locked in the apartment and only allowed out for short, closely-supervised trips. She and another woman, "Jiyun," never saw their earnings and eventually ran away with the help of a sympathetic webcam client and a South Korean pastor known for helping defectors.

North Korea is widely considered to be one of the worst nations in the world for human trafficking, with women and children in particular targeted for sex trafficking within the country. Female students and workers may be pressured to engage in sexual acts with authority figures and, if they seek to leave, could face much the same treatment in China. Other than webcam work, they may be coerced into working at brothels or find themselves sold into marriage with men. Given that these women almost always lack the identification needed to travel officially through China and may be returned to North Korea if caught, they are all the more trapped in exploitative and harmful situations.

Defectors may have to navigate harsh terrain

While some peple have been able to leave North Korea with relatively little fanfare or physical effort, other defectors have had to contend with seriously difficult environments. For some, it's all about the weather. North Korea can get intensely cold in the winter, with temperatures in the north of the country hitting a mean of -10 degrees Fahrenheit in January. While this means that rivers often freeze over and allow for crossings on foot, it obviously makes other parts of the passage more difficult, especially if defectors have poor cold-weather gear or are suffering from malnutrition. Yet it may not be better to stay put, as defectors may already have been struggling with a harsh existence while still in North Korea, where people in poor rural communities suffer during frigid winters.

Two defectors, "Mira" and "Jiyun," told the BBC that, after escaping a years-long sexually exploitative situation in China, their journey onward to South Korea involved tremendous physical effort. At one point on their long journey, they undertook a five-hour mountain climb that left them exhausted and bloodied by the time they finally reached a South Korean embassy. Other defectors may likewise find that they have to trudge or hike long ways on foot, or endure long journeys by car and bus. Defectors who aren't used to auto travel may find this car sickness-inducing part of their trip especially hard to bear.

Border guards have allegedly been ordered to shoot on sight

While some defectors have been able to make it across the border undetected, increased patrols in recent years have made such a feat more and more difficult. And it's not just that anyone fleeing the DPRK may be caught, handled roughly, and then turned over to a prison camp for back-breaking labor. They may simply be shot with little warning.

The issue came to broader international attention after Daily NK posted a photo of a poster that allegedly claimed anyone caught intruding into North Korean territory over its northern border would be shot on sight. The letter raised the concern of watchdogs in many quarters, including the United Nations, though North Korean officials have never made it clear if these are genuine orders.

Yet multiple defectors claim to have been fired upon by guards at either border. In November 2017, video footage of Oh Chong Song's defection across the DMZ shows him running while under fire. Though he was hit five times, Oh survived and even told NBC News that he didn't blame his fellow soldiers. Oh claims that if he was still a guard and facing the sort of pressure they were under, he would have taken up a gun, too.

Families of defectors can face serious consequences

With increasingly tight border controls and draconian security measures put in place throughout North Korea, many defectors have come to accept that they may never see or even communicate with their families again. Yet that may seem bearable, so long as their family doesn't suffer the grim fate of other defectors' loved ones.

According to Radio Free Asia, families of defectors have faced harsher punishments in recent years as the North Korean government seeks to quash hopes of leaving the tightly-controlled country. A source told RFA that, in July 2022, families with two or more escapees were rounded up and moved to rural areas with few resources. With defectors now labeled as traitors to the regime, their families' punishments also reportedly include prison time for taking money from escaped family members or even simply saying nice things about them in public.

Some families may even face terms in prison camps for the offense of being related to a defector. A source told Daily NK that one family was caught receiving money from a member in the south. After they were turned in by a broker, security officials arrested them and declared that they were all spies who had been accepting payment from South Korea in exchange for intel.

Surveillance makes it difficult to defect

According to the South Korean Ministry of Unification, the number of defectors from North Korea has been plummeting. The highest recorded number of defectors came in 2009 when 2,914 North Koreans sought refuge in South Korea. A mere 229 came to the country in 2020. Only 63 did the same the next year.

One increasingly prominent reason for this fall in defection is surveillance. Many North Koreans are observed via inminban, or "people's groups." Inminban leaders are well-situated to control and observe their neighbors through regular meetings. They report their local goings-on to higher-ups within the government. The Ministry of State Security may also pay others in the community to keep tabs on everyone. Practically anything is subject to observation and suspicion, from travel to financial activity, to what someone reads or watches in the seeming privacy of their own home.

As the DPRK moves into the 21st century, technology has taken on a larger role in controlling North Koreans and discouraging defection. Anyone with a smartphone is now required to install the Kwangmyong app to access the country's intranet or to get quarterly communications licenses, as an in-country source told Radio Free Asia. Yet the app also allows officials to track users' locations and activity. While some have simply refused to install the app or use Chinese phones smuggled across the border, this technological advance still makes it all the more difficult for someone seeking out resources to flee the country.

Chinese authorities may return defectors

While leaders in the DPRK already make it hard for people to defect, anyone who finds themselves over the border and in China isn't out of danger just yet. In past years, Chinese authorities have turned a bit of a blind eye to North Koreans moving across the border, but more recent reports indicate that those days are over.

In 2021, China began returning North Koreans held during COVID-19 border lockdowns, with Human Rights Watch reporting that a minimum of 1,170 North Korean defectors were detained as of July 2021. Defector Lee Seongmin told New York magazine in 2017 that China had already been pressuring embassies in Beijing to turn away North Koreans for years. Officials reportedly feared raising tensions with the DPRK if they allowed defectors to pass through the country.

While Human Rights Watch and other groups argue that defectors are refugees fleeing an oppressive regime, China doesn't agree. Instead, defectors are deemed "economic migrants" who are to be rounded up and deported to the DPRK. However, as escapees who are sent back to North Korea face sentences in prison camps that could arguably be called torture, China may well be violating the United Nations Convention against Torture and other international refugee agreements.

North Koreans may have a hard time acculturating to South Korea

Though North and South Korea were once part of a single nation, the effects of Japanese occupation and World War II tore the country apart, leaving it as two proxy states by August 1945. That division has led to serious cultural differences between the two nations. In communist North Korea, media consumption, clothing styles, freedom of expression, and more are all strictly controlled by the government. South Korea, by contrast, is a capitalist nation with open Internet access and a thriving entertainment industry. As a result, defectors can experience significant culture shock upon their arrival.

To alleviate this, many find themselves routed to the Hanawon resettlement center. There, they go through a three-month course meant to acculturate them to South Korean life. For many North Koreans, this may be the first time they are asked to manage a bank account, operate an unhindered cell phone, or log onto the Internet. Other workshops focus on women's rights and mental health, topics rarely discussed in more patriarchal and conservative North Korea.

Even language may present a barrier. While everyone on both sides of the DMZ speaks Korean, the dialect of the DPRK is often immediately noticeable in the south. South Korean words that have been adapted from English don't make crossing this linguistic border any easier, nor do Soviet-inspired ones from the north. A growing body of translation apps and north-south dictionaries can help, but defectors often still need language courses.

COVID restrictions increased border controls

With the arrival of the COVID-19 pandemic in early 2020, North Korea quickly moved to close its borders, all in an apparent attempt to keep the virus from burning through its population and stressing the country's poorly-maintained healthcare system. Yet this also provided a convenient excuse to crack down on anyone crossing into China illegally, as well as domestic travel within the DPRK. This followed years of increasing control after current leader Kim Jong-un came to power, increasing the difficulty and danger of defectors' journey with more physical barriers and a tightened surveillance network.

While North Korean leaders claimed that the near-total lockdown of its borders was necessary to contain the spread of COVID-19, others have argued that the measures have gone too far. North Koreans who were thinking of defecting once only had to consider frozen rivers and gun-toting guards, at least at some points along the Chinese-North Korean border. Now, that border is increasingly packed with sturdier fencing, watchtowers, and increased patrols. Besides discouraging defectors, these measures have also hit the black market economy in the nation, which allowed for the smuggling of food, medicine, foreign media, and other goods into the DPRK.

Life in South Korea can be full of discrimination

Once North Korean defectors have gone through a resettlement center, they are allowed to begin their lives in South Korea. But while the Hanawon and similar programs may seek to ease the transition, North Koreans can still face significant issues in their new home. Finding employment may be difficult when defectors are pitched against South Korean job applicants who have more standard educational backgrounds and may have already gone through interview processes before. As a result, defectors tend to have lower incomes and higher unemployment rates than those born in-country, though South Korea does provide a free college education for many of them and the income gap is reportedly closing.

They may also face social discrimination. Whenever Kim Jong-un or other North Korean leaders have fired missiles or are engaged in another round of warlike posturing and incendiary rhetoric, defectors may find themselves subject to extra scrutiny from their neighbors. Even North Korean children may face bullying in South Korean schools because of their backgrounds and accents. For some defectors, this is enough to push them beyond South Korea and into settling in other nations. A small number may even feel compelled to do something that sounds truly drastic after everything they've been through — return to North Korea.