The Rosenbergs: The 1950s Trial And Execution That Shook The World

The Cold War was a time in American history characterized by intense paranoia and division in all spheres of society. The crumbling wartime alliance between the United States and the Soviet Union degenerated into an ideological face-off between western capitalism and the growing threat of communism, which still underpins geopolitical struggles today.

Fears that the forces of international communism would eventually infiltrate western democracy led to some truly harrowing policy decisions by the U.S. government, particularly after the surprising speed with which the Soviets managed to develop their own atomic bomb. They detonated their first successful test in 1949, years earlier than the U.S. expected. Their success with such a small team, compared to the massive American Manhattan Project, raised concerns that the U.S. atomic weapons program — and possibly the wider military research institutions — had been infiltrated by Soviet spies, leading to a wide-ranging investigation to uncover them.

Two of those arrested for espionage in the early 1950s were a New York couple named Julius and Ethel Rosenberg. Not only were they put on trial and found guilty, but they were also sentenced to death in 1951, becoming one of the most sensational and controversial news stories of the decade. Here is what happened.

Who were Julius and Ethel Rosenberg?

At the time of their arrest, the most shocking aspect of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg for many Americans reading about them was that they appeared to be normal everyday people, on the face of it at least.

Born in 1918 and raised in a Polish immigrant household in Harlem, Julius developed a devotion to his family's Jewish faith during his childhood, and, while still a teenager, a deep respect for the labor movement. Later, as an electrical engineering student, Julius' political journey took him farther to the left, and he became a prominent member of the Communist Party of the United States of America.

It was through the Communist Party that he met Ethel Greenglass, a fellow New Yorker two years his senior of similar political beliefs, who helped the fiery young Julius with his engineering homework. According to Sam Roberts' biography "The Brother: The Untold Story of the Rosenberg Case," Ethel had good reason for wanting to see Julius graduate as soon as possible: Her family hadn't taken to him during early meetings due to his vulgar manners at the dinner table, and they were concerned that she would have to support him on her clerk's salary were their relationship to develop. In return, Julius tutored Ethel's younger brother, David, in engineering, and the pair became close friends. With Ethel's help, Julius did graduate, and the pair married in 1939, later having two sons, Michael and Robert. Ethel worked as a clerk, while Julius took an engineering job in the U.S. military.

Julius' journey into espionage

Julius Rosenberg had a long history of radical political activism throughout his student years and beyond, and was known to expound communism to people he met with the use of leaflets, according to "The Brother: The Untold Story of the Rosenberg Case." Nevertheless, when he applied for a position as an engineer in the U.S. military in 1940, he was forced to lie about his past political affiliations and covered up the fact that he had been a member of the Communist Party of the United States of America. Julius was recruited as a Soviet spy in 1942, tasked with recruiting fellow communist sympathizers as spies, and providing his handlers with information regarding American atomic research.

Through a Soviet spy named Alexandr Feklisov, who served as Julius' handler and wrote "The man behind the Rosenbergs," details of the working relationship between Julius and his communist counterparts have emerged. Feklisov claims that through a sizeable network of Soviet sympathizers built by Julius, the Soviets were provided with ample material to aid their weapons program, including a fuse that Julius himself smuggled out of his military research facility by volunteering for garbage duty (per Ronald Radosh's book "The Rosenberg file").

Julius smuggled a huge amount of information out of the research facility in which he worked, as well as considerable material relevant to the Soviet's development of atomic weapons from other spies he had recruited, including Ethel's brother, David Greenglass, who worked on the Manhattan Project.

How the Rosenbergs were arrested

Julius Rosenberg wasn't the first American to be identified as a spy during the U.S. investigation that followed the 1949 Soviet atomic bomb detonation. Rather, the house of cards came crashing down on February 2, 1950, after a German scientist named Klaus Fuchs confessed to investigators in Britain — where he had been working — that he had been collaborating with the Soviet Union. Fuchs had been providing the Soviets with atomic secrets to speed up the development of their own weapons of mass destruction, according to the FBI, who led the investigation into potential spies in the U.S.

Fuchs claimed to have been working with an American contact known only as "Raymond," who was later identified by the FBI as a man named Harry Gold. Through Gold, the FBI secured numerous confessions from people in Julius' spy ring, including his brother-in-law David Greenglass, who said that he and his wife, Ruth, had been recruited to the spy ring by the Rosenbergs. Greenglass' grand jury testimony would later prove to be damning for the Rosenbergs.

A brother's betrayal

The arrest and confession of David Greenglass proved decisive to the FBI's investigations into Soviet spy rings in the U.S. military: ultimately, it would lead them not only to Julius Rosenberg but also to his wife, Ethel, David's sister.

The younger David had grown particularly close to Julius in his adolescent years. As well as encouraging and offering guidance to David in the fields of science and engineering, Julius also influenced his young mind politically and essentially molded him into a communist sympathizer. Sam Roberts has argued in "The Brother: The Untold Story of the Rosenberg Case," however, that while David joined Julius and Ethel in their political activities, he was driven more by a need for their approval than any true heartfelt loyalty to the Soviet cause, which may explain his later actions.

Under oath following his arrest in June 1950, Greenglass agreed to collaborate with the FBI, and testified that Julius was the senior party in the alleged Soviet spy ring. Later, he went a step further, changing his testimony to say that Ethel, too, had been actively involved, typing up secrets that Greenglass had supplied to Julius to pass to his handlers. In yet another hurtful blow, Ethel's family decided to believe Greenglass' version of events, and decisively renounced their daughter for her actions as a result, according to Ilene Philipson's "Ethel Rosenberg: Beyond the Myths."

The Rosenberg's trial

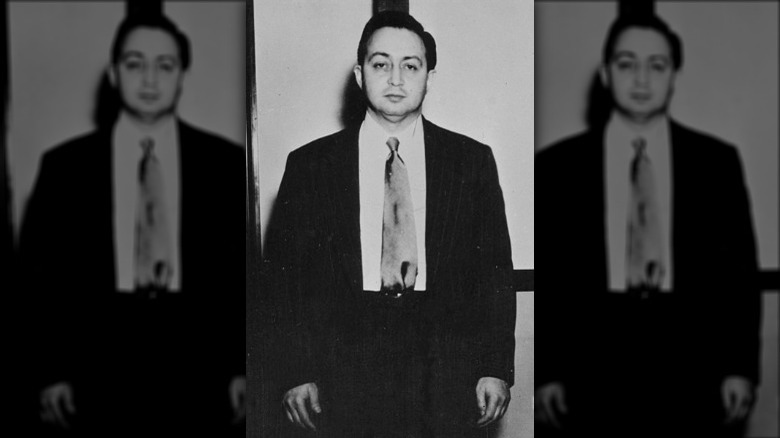

The trial of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, as well as Julius' college friend and co-conspirator Morton Sobell (pictured), began on March 6, 1951, some six or seven months after their arrests. Witnesses included friends and colleagues that Julius was accused of approaching and inviting to join him in atomic espionage, including David Greenglass, who gave a detailed account of his indoctrination and recruitment by the Rosenbergs and the information he later provided to them, according to "Invitation to an Inquest" by Walter and Miriam Schneir. The Rosenbergs maintained their innocence throughout, and refused to name other Soviet sympathizers.

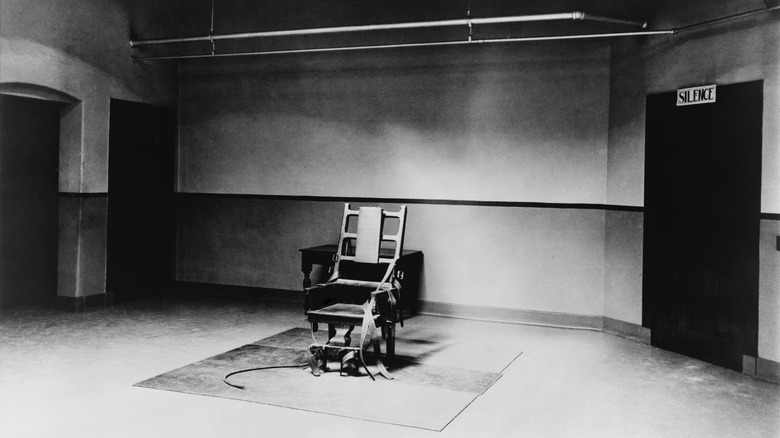

On April 5, Judge Kaufman, who had presided over the case, handed down his sentence. Though espionage usually carried a maximum sentence of 20 years imprisonment, the law stipulated that espionage during the war could be punishable by death. As such, Kaufman sentenced the Rosenbergs to be executed in Sing Sing, and sentenced Sobell to 30 years in prison. His statement during the sentencing was damning. Kaufman described the actions of the Rosenbergs as a "crime worse than murder," and explained his belief that, by aiding in the expediency of the Soviet atomic program, Julius and Ethel Rosenberg had emboldened communist causes in the Korean War (1950-1953), causing some 50,000 unnecessary casualties.

By pleading not guilty and refusing to collaborate, the Rosenbergs were seen as remaining loyal to the Soviet cause even in the face of death, which would leave their two sons, Michael and Robert, orphans. Kaufman addressed their plea with the brutal closing line: "Love for their cause dominated their lives — it was even greater than their love for their children."

The National Guardian

In its final statement before the death sentence was passed down to the Rosenbergs, the couple's defense team outlined why they should be saved from the electric chair. These included their doubts that the information they had supplied to their handlers had directly impacted the Soviet atomic effort, and argued that their performing espionage on behalf of a wartime ally should excuse them from a death sentence. These arguments were maintained by their supporters even after sentencing, along with the belief that Ethel Rosenberg was not involved anywhere near as much as the prosecutors and her brother David Greenglass had claimed.

According to "Encyclopedia of the American Left," one prominent organ that maintained its steadfast support for the Rosenbergs, even after sentencing, was the left-leaning periodical The National Guardian, which became central to an international effort to have their sentences quashed. As well as hard-hitting editorials arguing their case, The National Guardian regularly carried letters from the Rosenbergs themselves, who told readers: "We are an ordinary man and wife ... Like others we spoke for peace, because we did not want our two little sons to live in the shadow of war and death ... That is why we are in the death house today ..." (per "The Rosenberg File").

People protested against the sentence

It is argued in "The Rosenberg File" that direct testimonials from Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, published in the wake of their death sentences, may have hindered their legal team's attempts to appeal their sentences. However, it is certainly true that a groundswell of support for the doomed couple emerged following their arrival on death row and coverage in The National Guardian.

According to Phillip Deery, Emeritus Professor of History at Victoria University, Melbourne, the couple's supporters channeled their efforts into an organization titled the "National Committee to Secure Justice in the Rosenberg Case." This was otherwise known as the Rosenberg Committee, and was formed in October 1951 as a fund-raising and activist collective. Though some historians have claimed that the Rosenberg Committee was nothing more than a front for the Communist Party of the United States of America, Deery claims that the organization was a genuine grassroots attempt by an "organic" affiliation of intellectuals to save the Rosenbergs from an immoral government-approved death.

The movement also garnered support overseas, especially in France, where the existentialist writer Jean-Paul Sartre wrote several spirited tracts attacking the U.S. government over the Rosenberg case. Many of their defenders also made clear that they believed there was an anti-semitic aspect to their conviction and sentencing.

President Eisenhower refused clemency

The Rosenberg Committee had built such a head of steam by the end of 1952 that the Rosenberg's defense team, led by their lawyer, Emanuel Bloch, had submitted an official request to President Harry S. Truman for clemency. Truman, however, had long been battling to prove that his administration was serious about the threat of communism. Though it seemed he was concerned about the political fallout from the unprecedented execution of two married Americans on espionage charges, he never responded to the Rosenberg Committee before the end of his presidential term in January 1953, according to "Invitation to an Inquest."

The responsibility then fell to his successor, Dwight D. Eisenhower. And where Truman had drawn the issue out, Eisenhower was firm and decisive. In what became front-page news, the new President announced on February 11, 1953, that the call for clemency had been denied. His speech echoed the sentiments of Judge Kaufman, that the actions of the Rosenbergs had unjustly threatened the lives of innocent Americans, adding: "There has been neither new evidence nor have there been mitigating circumstances which would justify altering this decision."

The execution of the Rosenbergs

As well as the Rosenberg Committee's direct appeals to the President, they appealed a reported six times to the Supreme Court to have the Rosenbergs' death sentences lifted, with no success. Seemingly from nowhere, however, a hitherto unknown Nashville lawyer named Fyke Farmer succeeded in securing a stay of execution for the Rosenbergs, pushing the date back from June 17 to June 19 at the last moment.

The days before their execution descended into something of a grim farce. The Rosenberg Committee objected to the planned date of the execution — 11 p.m. on Friday, June 19, 1953 — which fell at the start of Sabbath, claiming that it was disrespectful to the couple's Jewish heritage, according to The New York Times. Judge Kaufman agreed, and, instead of another stay of execution, the time of their deaths was brought forward by three hours.

Julius went to the electric chair in Sing Sing before Ethel, where he received three electric shocks and was reportedly dead in an instant. Ethel, who in the minutes before 8 p.m. had attempted once more to appeal to the mercy of President Eisenhower with a handwritten letter — to no avail — then went to the chair. The gruesome reality was that her execution was botched: Having struck her with what was believed to be a fatal dose of electricity, it was found that her heart was still beating. She had to be given a total of five shocks, which a witness claimed caused Ethel's head to smoke in its final throes, according to "Ethel Rosenberg: Beyond the Myths."

The Rosenbergs' impact on the USSR atomic weapons program

Outrage following the deaths of the Rosenbergs failed to lift, especially as Americans came to terms with the fact that the decisions of the justice system had left two innocent children orphaned. The question, then, became whether the death sentence was really justified.

The debate that continued after the Rosenbergs' deaths tended to focus on a central assumption made during their trial: The communist sympathizers had been crucial to the Soviet Union detonating an atomic bomb as early as 1949, and the repercussions this had on the Korean War. The memoirs of the former Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev seem to reinforce the findings of Judge Kaufman, in his appreciative claim that the Rosenbergs "rendered us very essential assistance in speeding up the development of an atomic bomb."

However, other Soviet sources closer to the atomic program have contested whether the Rosenbergs were quite so instrumental as was generally assumed. One leading atomic engineer told The New York Times in 1989 that he believed the that the Soviets gained little from the Rosenbergs' espionage efforts, and that the United States had "sat the Rosenbergs in the electric chair for nothing."

Was Ethel Rosenberg innocent?

In the many decades since the execution of Ethel and Julius Rosenberg, another point of fierce debate is the question of whether the United States was right in handing down a death sentence to Ethel, as well as Julius. In truth, even before the execution, figures such as FBI director J. Edgar Hoover reportedly worried about the optics of sending a woman to her death along with her husband, and leaving her children motherless.

As the years have passed, the Rosenberg's sons, Michael and Robert, have been at the forefront of efforts to have their parents pardoned by the U.S. government. In 2008, the brothers finally conceded their misguided belief to The New York Times, following a new confession from the spy Morton Sobell, that their father Julius did indeed pass information regarding American atomic weapons to the Soviet Union. They have, however, continued to campaign on behalf of Ethel, using FBI documents newly unsealed in 2015 to show that Ethel was used as a "lever" against Julius, in a failed attempt to extract a confession from him (via The Washington Post). However, no pardon has been forthcoming for either of the Rosenbergs.

Could Julius Rosenberg have been saved?

As more and more details of the Rosenberg case come to light, that Julius Rosenberg was an active and seemingly enthusiastic spy for the Soviet Union, before his arrest in 1950, has been roundly accepted . But it has also been argued that his life could have been spared, like those of his numerous collaborators, such as Morton Sobell and David Greenglass.

As noted in Feklisov's "The Man Behind the Rosenbergs," there is reason to believe that the Soviet security services, the KGB, had options for saving the life of their American spy, who had fed them thousands of classified documents throughout the 1940s. Feklisov asserts that the U.S. and the USSR might feasibly have traded captured agents, had the Soviets been willing to admit that Rosenberg had been collaborating with them. If not, they might have at least advised him in some capacity how to proceed in court, to avoid receiving a death sentence. He argues the USSR might even have supplied him with a legal team.

But by the time the USSR had finally conceded that Julius Rosenberg was working for them, he and his wife Ethel were long dead, in one of the darkest and most troubling moments in Cold War history.