Robin Hood Myths Most People Believe

Robin Hood legends have been popular for centuries, and books and movies about the daring outlaw in Sherwood Forest outsmarting the cruel Sheriff of Nottingham are still thrilling audiences today. These stories have become so iconic that it can be hard to imagine that there was ever a time when Robin Hood was not the king of the bandits leading his loyal Merry Men to rob the rich to give to the poor.

Legends are not stagnant, however. Folklore changes and adapts over time to reflect the hopes and fears of its audiences. In the hundreds of years that people have been sharing stories about the legendary outlaw, the early ballads and legends have developed into entirely different types of stories. Robin Hood is a staple of modern pop culture, but many of the most basic facts about Robin Hood and the characters that people expect to see in his stories have changed. Many beliefs about Robin Hood that modern audiences take for granted either were not always the case or were never true at all.

Myth: He was a historical figure

Many believe that Robin Hood was a real person. While there's plenty of evidence that the folk stories about Robin Hood and his band of Merry Men are mostly fictional, it's easy to understand where this misconception came from. Robin and his friends are typically described as hiding from the law in Sherwood Forest: a place that really exists. Some of the most famous characters in Robin Hood stories, like King Richard the Lionheart, were real people. The majority of modern Robin Hood books and movies are set in the 12th century. With Robin Hood so firmly anchored into a specific time and place in history, it makes sense that people believe that he was real. In reality, though, Robin Hood was almost certainly a folk hero, with bits of the legend coming from real historical events and older myths.

Robin Hood may be a mythological figure, but some elements of his story are very real. As described in James Holt's "Robin Hood" it's likely that the exploits of the famous outlaws Hereward the Wake, Eustace the Monk, and Fulk Fitz Warin inspired some of Robin Hood's most daring adventures. Hereward led his loyal followers to violently oppose the Norman Conquest. Eustace left his monastery to get revenge on those who had killed his father and spent some time in the woods as a bandit. Fulk was a disinherited baron who rebelled against Robin Hood's most famous adversary: King John.

Myth: Robin Hood is definitely a name

Robin Hood, as he appears in popular culture, is almost certainly a legend, but that doesn't mean that there was never a real bandit called "Robin Hood." In fact, there were many.

Historians like James Holt have discovered many examples of outlaws who have been called not "Robin Hood" but "Robinhood." As described by Professor Graham Black for History, before the year 1400, there were eight different examples in court records of outlaws being referred to as Robinhood. This wasn't their real name – it was likely a nickname or title given to them by the court clerk because they were bandits.

It is believed that this may have been a title or nickname which outlaws gave themselves, too. Medieval criminals may have assumed this identity to protect themselves. Some even believe that these bandits adopted the pseudonym Robinhood as a tribute to a famous and feared outlaw who lived sometime before the first instance of the nickname in the early 1200s, but no evidence of this mysterious figure has been found in historical records.

Myth: He was always heroic

Today, Robin Hood is a heroic character, robbing the rich to give to the poor. He stands up to oppression, fights for the rightful king, gives up his lands and titles, and becomes an outlaw to do what he thinks is right. In early ballads about Robin Hood, he can be a far less heroic figure.

In most popular Robin Hood stories that we know today, Robin Hood's crimes are justified by the corruption of the local sheriff and by the fact that the king in power, King John, is not the rightful king of England. In the older ballads, however, Robin and his followers are not protesting an unjust regent – they're just bandits. Robin Hood and his band of followers do target corrupt wealthy people, but they never seem to have any plans to redistribute that wealth to poor peasants.

Robin Hood stories have been told and retold for hundreds of years, and his stories evolved over time for changing audiences. In the 1400s, the stories became more overtly about class conflict. One of the most popular Robin Hood legends features Robin being turned in to the sheriff by a corrupt monk. Robin Hood's men kill the monk and then assume his identity to free their leader. In general, Robin Hood stories have made him more heroic over time, but in the 1700s it became popular to depict him as a violent criminal, and he was included in titillating books about brutal murderers.

Myth: He was an earl

In modern Robin Hood stories, he is forced to give up his land and title, fleeing into Sherwood Forest. While written references to Robin Hood predate the Canterbury Tales and the character himself is likely even older, Robin Hood wasn't depicted as part of the nobility until 1601, when playwright Anthony Munday released a play about Robert, Earl of Huntingdon, better known as Robin Hood. While Munday's plays about Robin Hood are rarely performed in modern times, his idea that Robin Hood was an earl stuck, and became a part of many modern retellings.

Older ballads depict Robin Hood as a hero for the people. Rather than a noble who tragically lost his title, he is a poor yeoman bandit. He is not even depicted as the captain of the Merry Men, instead, they seem to be a band of equals living in the forest together. This medieval version of Robin Hood was likely social commentary, wish fulfillment, and inspiration for the lower-class peasants who told the stories.

In the 16th century, Robin Hood legends were seen as dangerous to the aristocracy, and making the hero a member of the upper class dulled the edge of Robin Hood's social commentary. Robin Hood legends have managed to remain controversial, however. During the Red Scare in 1950s America, there were calls to remove all references to Robin Hood from Indiana state textbooks due to fears that reading Robin Hood stories would encourage children to be communists.

Myth: Robin Hood was fighting for King Richard

In most popular depictions of Robin Hood today, Robin is an outlaw because of the machinations of the villainous Prince John, who has usurped the throne from his noble brother King Richard the Lionheart. The idea that Robin Hood was an outlaw because of his loyalty to King Richard was popularized by the Elizabethan playwright Anthony Munday, and remains a standard motivation for the character today.

However, as detailed in R.B. Dobson and John Taylor's "Rymes of Robyn Hood: An Introduction to the English Outlaw" there is no reason to assume that, if there ever was a real bandit who inspired the Robin Hood legends, he would have lived during the reign of King Richard I or King John. The earliest ballads about Robin Hood, which emerge a century or two after Richard I's death, make no mention of King Richard. If this early Robin Hood has any political opinions other than violent opposition to wealth and corruption, he keeps them to himself.

Myth: Richard the Lionheart was a great king

Famously, Robin Hood robs the rich to give to the poor. However, in many of the depictions of Robin Hood that are popular today, including the 1938 Errol Flynn adaptation, Robin is saving the plunder from his banditry for someone else: the King of England. Robin Hood is often depicted trying to raise the money to pay King Richard's ransom, which his deceitful brother Prince John is choosing not to pay to keep the rightful king imprisoned in a foreign land. Richard the Lionheart really was captured and exchanged for ransom – but the historical King Richard may not have deserved the unquestioning loyalty he receives in Robin Hood legends.

As recounted in an article by Michael Maekowski published in the "Journal of Medieval History," Richard is often characterized by historians as a selfish and unpleasant person and a terrible ruler, whose only real interest was waging war. He led his army on multiple crusades, attempting to capture Jerusalem for the Pope. Richard I was a brutal battle commander and was believed to have killed thousands of civilians on his quest to capture the Holy Land – which he never did. King Richard nearly bankrupted England when he was actually captured and held for ransom in Germany. It is believed that the myth that Richard was a chivalrous and worthy king comes directly from propaganda created by his mother Eleanor of Aquitaine, which was designed to encourage raising the money to pay his ransom.

Myth: There was a Sheriff of Nottingham

Robin Hood's most famous antagonist is the Sheriff of Nottingham (pictured being portrayed by Peter Cushing in the 1960 film "Sword of Sherwood Forest"). The sheriff is a corrupt and brutal figure, typically depicted as Robin's opposite: taking money from the poor to line his own pockets. It's highly unlikely that this famous villain ever really existed, but that doesn't mean that his cruel exploits weren't inspired by real events.

In reality, there was no Sheriff of Nottingham until 1449, at which point legends about Robin Hood had already been told for decades. Any real bandits who inspired the stories of Robin Hood certainly didn't live at the same time as anyone with the title "Sheriff of Nottingham."

However, there certainly were corrupt sheriffs during the reign of King John, and it is believed that the Sheriff of Nottingham was inspired by them. As described on historian and Robin Hood expert Alan W. Wright's website, sheriffs didn't earn a salary and had to pay the crown for the privilege of calling themselves sheriff, so there was a major incentive to overtax the people. That surplus income went directly into the pockets of the sheriffs. Many took bribes and extorted the people they were supposed to protect with threats of false imprisonment.

Myth: Robin Hood was the only person rebelling against King John

In modern Robin Hood stories, King John is the villain behind all of the corruption and cruelty that Robin Hood and his Merry Men are fighting. While Richard the Lionheart's reputation as a good king is probably underserved, King John certainly earned his reputation as a bad king. Often in Robin Hood legends, it can seem like Robin Hood is the only person standing up to King John's tyranny, but in reality, the majority of English nobles would have been on Robin's side.

As in the legends, the real King John did attempt to take the throne while King Richard was captured. He was unsuccessful but still became king after Richard's death in 1199. Five years into King John's reign, he lost Normandy and Anjou to France. He raised armies and attempted to take this land back from France, but doing so cost England a massive amount of money. He raised taxes dramatically, which led to a major conflict between King John and his barons. In 1215, the barons rebelled against King John and forced him to sign a list of rules that kings would have to follow from then on. This is known as the Magna Carta. While King John largely ignored these rules, it forever changed the future of English politics by establishing the idea that there were rules even kings had to follow.

Myth: He was from Loxley or Huntingdon

In the legends, Robin Hood is often referred to as "Robin of Loxley" and "Earl of Huntingdon." Historians have attempted to track down evidence of Robin Hood in both places, but no real historical Robin Hood has emerged.

A 1600s account claims that Robin Hood was born in "Locksley," which many, including historian and Robin Hood expert Alan W. Wright, believe likely refers to a village in Yorkshire called Loxley. Some believe that it actually refers to another Loxley, located in Warwickshire, where a man named Robert Fitz Odo lived in the late 12th and early 13th century. However, there is no reason to assume this Robert was the inspiration for Robin Hood, or was ever an outlaw.

The earliest Robin Hood legends do not describe Robin Hood as an earl of anywhere, but as later storytellers made him nobility, Robin Hood needed an official title. It is believed that Elizabethan playwright Anthony Munday was the first to declare Robin Hood the "Earl of Huntingdon." This title may have been chosen at random, but the real Scottish earl who controlled Huntingdon during the reign of Richard I does share some interesting traits with the legendary Robin Hood, including losing his title for a decade after rebelling against a king.

Myth: Maid Marian was always Robin Hood's love interest

One of the characters most associated with Robin Hood is Maid Marian. Sometimes, she is a noblewoman in love with Robin Hood even though he is an outlaw. In other stories, she is an outlaw herself, living in Sherwood Forest and fighting alongside the Merry Men. Today, she is an essential part of the Robin Hood story, but the early Robin Hood legends and ballads don't include Maid Marian or any other love interest.

Both Maid Marian and Friar Tuck became a part of Robin Hood's story through the May Day festival. As described in an article by W.E. Simeone published in The Journal of American Folklore, in the 15th century, Robin Hood became a major part of the May Games, being celebrated throughout England and Scotland for almost 300 years. Robin Hood was a character already known from ballads and songs, but he became immensely popular in May Day performances. In fact, according to Ronald Hutton's book "The Stations of the Sun: A History of the Ritual Year in Britain," Robin Hood was such a popular character in May Day performances that he ended up replacing the king of the revels at many festivities. Maid Marian was an unrelated character in the May Games, likely representing a maiden of the dawn or a sea goddess, but over centuries of the two characters appearing together at festivals, she started showing up as a character in Robin Hood legends.

Myth: He always wore green

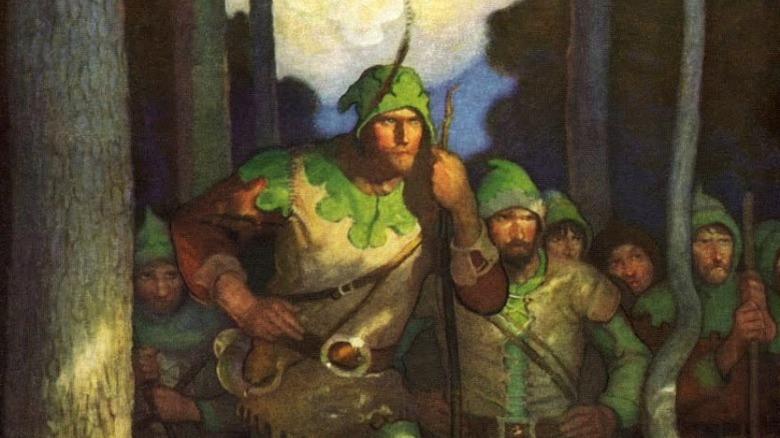

There have been many iconic depictions of Robin Hood which took different approaches to the protagonist, from the noble hero illustrated by N.C. Wyeth in the early 1900s to Errol Flynn's dashing rogue in 1938 or even Disney's tricky cartoon fox in 1973 (pictured). As different as these Robin Hoods are, they all wear green. While the color is closely associated with the character today, Robin Hood used to wear another color: red.

The connection between Robin Hood and green clothes dates back to a traditional ballad called "Robin Hood and Queen Katherine," which was already an old story when it was written down and published by folklorist Francis James Child in the 1880s. In this ballad, Robin Hood is described as dressing his men in the specific shade "Lincolne greene," while he himself wears scarlet red.

Today, a red costume is associated with another of Robin Hood's Merry Men: Will Scarlet. At the time, however, it made perfect sense for Robin to be the one in scarlet. As described by The Lincolnite, the city of Lincoln was well-known in the Middle Ages for making clothing that was dyed light green. Lincoln also had another, far more expensive specialty: Lincoln scarlet. Since at this point, the Robin Hood legend had evolved to depict Robin as a dispossessed noble, it makes sense that in the company of a queen, he would wear red.

Myth: His archery skills were supernatural

In an archery competition, Robin Hood's opponent gets a perfect bullseye. It seems like the competition is surely lost, but then, against all odds, Robin Hood fires his arrow directly into the arrow already in the target. By some accounts, he actually splits his opponent's arrow in two.

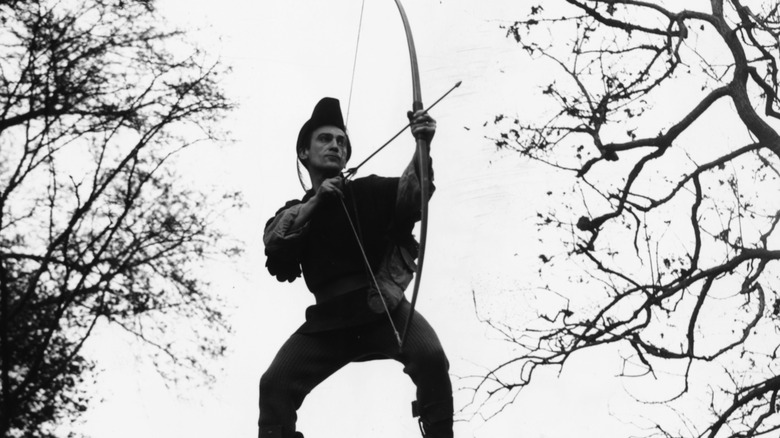

If Robin Hood has a superpower, it's archery. His skill with a bow and arrow astonishes his friends and enemies alike. With the incredible stunts the legendary Robin Hood is able to pull off with a bow and arrow, it makes sense that many assume that in real life they would be impossible.

However, splitting an arrow already in the target with a second shot is not outside the realm of human possibility. Modern archers call this trick shot "a Robin Hood," and it is possible with a tremendous amount of practice and skill. The question of if a Medieval outlaw would have been capable of splitting an arrow is still hotly debated, even today. The Mythbusters attempted to test it and were able to partially split an arrow, though they couldn't completely split it down the center. Some, like historian Thomas Ohlgren (as quoted by Slate), believe that the legend that Robin could split an arrow developed from a more common (but still impressive) test of skill from the era which involved splitting a willow stick in front of the target.