The Tragic Cocoanut Grove Nightclub Fire That Killed Nearly 500 People

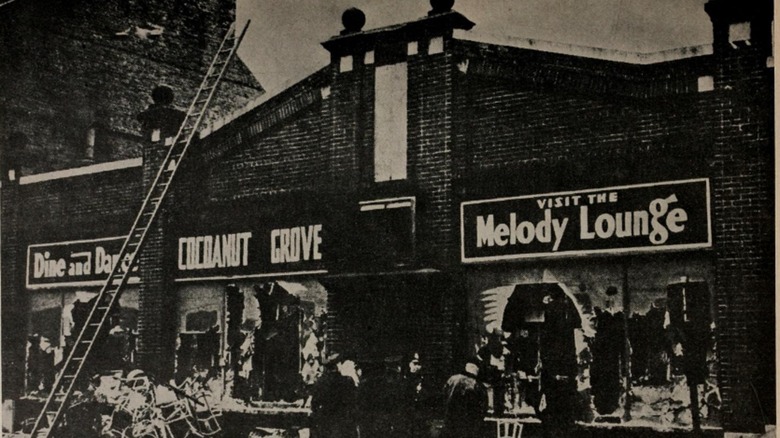

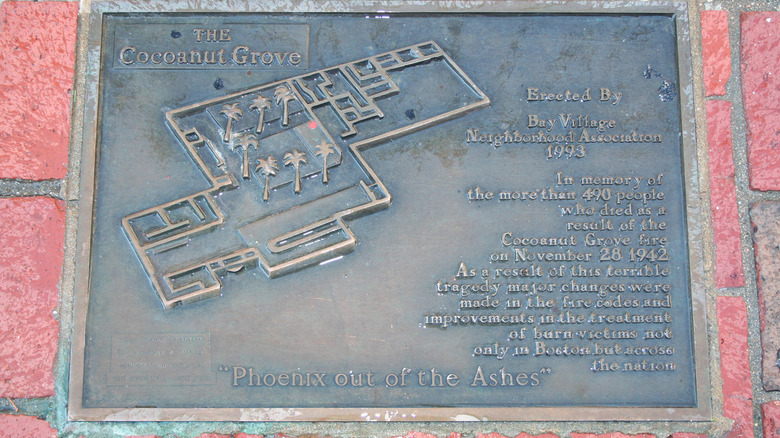

Boston, Massachusetts was witness to one of the most tragic nightclub fires in history. On the evening of November 28, 1942, at 17 Piedmont Street, 492 people died as a result of a sudden inferno at Cocoanut Grove, a downtown nightclub.

The National Fire Protection Association maintains a list of the deadliest fires and explosions in U.S. history. The Cocoanut Grove fire ranks as number seven on the list, just below a forest fire that killed 559 in Minnesota in 1918. Of building fires, Cocoanut Grove is the third deadliest, below the 1903 conflagration at the Iroquois Theater in Chicago, which killed 602, and the September 11 attacks on the World Trade Center, which killed 2,666 people.

The most tragic element about the Cocoanut Grove fire is that many of the deaths were preventable. People were the victims of human avarice and negligence. Yet it was because of this tragedy and the scrutiny over safety that followed that many lives in the ensuing decades were saved. Let's take a look at one of the most horrid events in U.S. history, the Cocoanut Grove fire.

The following article includes depictions of mass violence. If you have been impacted by incidents of mass violence, or are experiencing emotional distress related to incidents of mass violence, you can call or text Disaster Distress Helpline at 1-800-985-5990 for support.

Cocoanut Grove was owned by a gangster

As Stephanie Schorow recounts in "The Cocoanut Grove Nightclub Fire," the club first opened its doors on October 27, 1927. The club owners in those early years were divided over whether to illicitly sell alcohol during Prohibition since the club was having financial difficulties. The matter was settled in 1931 when the club fell into the hands of the gangster Charles "King" Solomon for an unrefutable offer of $10,000. Aside from bootlegging, Solomon was neck-deep in the illicit drug trade and loansharking.

Solomon was assassinated in 1933. The club then passed from Solomon's widow to the hands of his lawyer, Barnett "Barney" Welansky, who began to expand, refurbish, and reshape the venue to the form it took in the 1942 fire. The Boston Fire Historical Society possesses a collection of documents concerning the disaster, one of which is a floor plan of the establishment. Patrons visited the first floor, which featured dining rooms, a dance floor, a bar, and a cocktail lounge. There was also a lower level called the Melody Lounge, which the book "18 Tiny Deaths" tells us featured a revolving stage as well as ubiquitous tropical décor of paper, bamboo, and rattan. In other words, the bar was made up of pretty flammable materials.

What started the fire?

On the evening of November 28, 1942, Cocoanut Grove was bustling. It was the Saturday after Thanksgiving, and roughly 1,000 people jammed into the club.

At about 10 p.m. that night, a lightbulb went out in the downstairs Melody Lounge. Apparently, a patron had unscrewed it to create a more intimate ambiance for him and his paramour. A bartender ordered Stanley Tomaszewski, a 16-year-old busboy, to go replace the bulb. To do so, the teenager lit a match in order to be able to see. Tomaszewski blew out the match, but within moments a fire burst out amid the ceiling's palm tree decorations.

Tomaszewski was blamed for starting the inferno, and it may very well be that it was the cause. However, in the fire's official report, the cause was deemed indeterminate, and Tomaszewski was mainly exonerated. This was little consolation for Tomaszewski, who stayed at a hotel for months under an armed guard. "The Cocoanut Grove Nightclub Fire" explains how for the rest of his life, until he died in 1994, he would be subjected to all forms of harassment, including being spat upon and receiving threatening midnight phone calls. Before his death, Tomaszewski reportedly said, "I don't have a sense of guilt, because it wasn't my fault."

The Cocoanut Grove fire spread rapidly

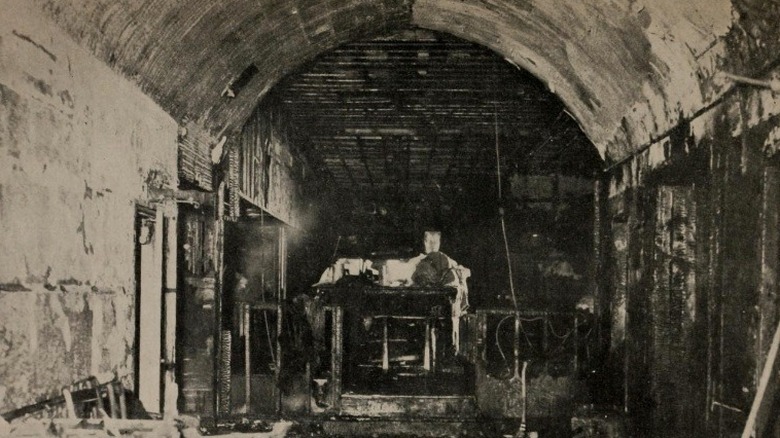

The fire was a wonder of death. "Egress Design Solutions," which analyzed the disaster, pointed out that the artificial plant décor in the Melody Lounge was so combustible that the fire instantaneously became an inferno despite the efforts of some waiters to put out the initial flames. The fire got into the ceiling, shot through corridors as a fireball, and then rapidly spread through the entire first floor, leaving victims panicking.

One patron, Henry Gaw, who was on the first floor, recounted, "A cloying, blinding, impenetrable pall of smoke dropped instantly from above and sounds of panic erupted from all directions." The ceiling burned, casting bits of fiery debris upon the victims.

As noted by "The 100 Greatest Disasters of All Time," fire trucks arrived at 10:20 p.m., at which point the club was already a burning, smoky wreck. There is no doubt that the responding firefighters would suffer more than a lifetime of nightmares from the horrors that they saw that night. One responder noted that the victims were so burned that "tongues [were] split open." Bodies were unrecognizable. And there were a lot of them. Firefighters entered masked and found the entryway "knee deep in bodies and they were like jackstraws, arms and legs and hands ... And some of the people's heads were right through the first section of wall, like through the plaster."

Its revolving door was a door of death

The final number of deaths from the fire has been tallied at 492 — an extremely high figure considering that the flames were extinguished within an hour. Most of these deaths were due to poor fire safety practices. One prominent deathtrap was the main entrance, which was serviced by a revolving door. When panic ensued, people rushed toward the entrance both from the basement and the main floor, converging and causing a bottleneck. After a couple of people escaped, it became jammed. This was worsened as the crowd behind was crushed against those by the door. The bodies stacked up rapidly.

What is very notable is that the revolving door was the only way in or out at the main entrance on Piedmont Street. There were no other doors available for people to escape. It is estimated by the Journal of Light Construction that at that location, approximately 200 people died in a heap. Furthermore, "Rescue Men" states the seating capacity of Cocoanut Grove was 460 and the general capacity of the club was 600. Yet the estimated total number of people in there that night was 1,000.

Poor fire safety at Cocoanut Grove led to the deaths

There were numerous problems with the club. Other exits in the building were obscured behind decorations or blocked by false walls. In some of these cases, the doors were locked. Ultimately, the only people in Cocoanut Grove who used these doors and knew of their existence were the staff.

A report from litigation over the fire highlights these problems. It noted, as an example, that although other exits were possible, they were totally confusing to navigate and one was sealed with a wooden bar. This was hardly desirable emergency egress and the report stated, "It is evident that an emergency escape from the Melody Lounge ... would be difficult for a patron not thoroughly familiar with parts of the premises not open to him."

Furthermore, the report stated that aside from the main entrance, there were five possible emergency exits to the building, some of which were equipped with panic bars. However, it was found that doors were locked on purpose, nonfunctioning, blockaded, or not visible.

The refrigerators came into play in multiple ways

It may sound odd, but the massive refrigerators and meat lockers at Cocoanut Grove may have proved critical both in the spread of the fire as well as a means of survival. There is a theory that due to war shortages, the club used methyl chloride as a substitute for Freon in the refrigeration units. It is theorized that the gas leaked from the unit, and being a flammable accelerant, caused the rapid spread of the fire through what is presumed to be an electrical short. This theory is supported by testimony from victims who said they felt sluggish and that they detected a sweet odor — which are common symptoms and traits of methyl chloride respectively.

However, there are discrepancies, particularly since the ceiling burned first and methyl chloride, being a heavy gas, would have been at floor level. It is also interesting to note that in the fire commissioner's official report, the fire appeared to be gaseous in character. Again, it is unlikely the cause of the fire will ever be truly known, but it likely enjoyed a perfect storm of factors that made it so deadly.

On the other hand, the refrigerators offered a chance of survival for escaping victims. Five, in fact, avoided death with the help of staff who locked themselves in one of the walk-in refrigerators.

Each survivor had a different tale of horror

It seems that any person who escaped that night had a different harrowing tale. One couple, Ferd Bruck and Cleo Lambridis were in the Melody Lounge but fortunately on the end closest to the corridor. They were one of the first to arrive at the revolving doors even with the heat of the flames behind them. Both managed to push through the revolving doors although they were burned. A taxi driver took them to Boston City Hospital, but the driver refused payment and stated he was going to return to the scene to help.

In another survivor's account, a teenage singer at the club, Dorothy Myles recounted how she was passing near the stairs leading down to the Melody Lounge when she saw light and heard a massive explosion. She was knocked down. Upon recovery, she made her way through the panic-stricken crowd in the dining room where she was crushed and broke her nose on a table. The crowd was trampling her but she managed to creep and crawl until she fell under a pile of the dead and dying. She was miraculously rescued although she was at the bottom of a sea of corpses. In her recovery, she underwent 10 skin grafts since she was so tremendously disfigured by the fire. While she eventually recovered, her career in entertainment did not.

The disaster at Cocoanut Grove was a five-alarm fire

The response to the fire was swift. An alarm was raised at 10:15 p.m. in response to a small automobile fire in the vicinity of Cocoanut Grove. After the firefighters extinguished the blaze, they saw smoke issuing from the club. From this point, the rising crisis resulted in more alarms until it became a five-alarm fire. That basically means the fire department called in more recruits and resources due to the scale of the fire. In the end, the battle against the fire resulted in 18 hose units being employed against the flames. These immediate responders were then soon joined by others, including Mayor Maurice J. Tobin, who coordinated the work of relief agencies such as the American Red Cross as well as civilian defense units. Members of the U.S. Armed Forces also assisted.

It seemed as if all bodies in the city had mobilized to help in the rescue and relief efforts. But for these responders, it was a grim scene. The fire commissioner found that the chief cause of death was the rapid spread of fire and the lack of workable means of egress.

It resulted in advances in medical treatments

Any significant disaster usually has the unwanted silver lining of subsequent advances. Some of these advances were medical, and others were psychological. First, there were burn treatments. The British Medical Journal reported that plastic surgeon Bradford Cannon abandoned the use of tannic acid and dyes to treat burns since they did more harm than good. Instead, he turned to the use of gauze with boric acid and petroleum jelly.

Second, psychologists started studying the impact of the fire on the victims. The New Yorker reported that Harvard psychiatrist Eric Lindemann studied numerous survivors from Cocoanut Grove to analyze how they coped with the grief of losing loved ones who were with them during the disaster. This has informed our modern theories of how humans deal with grief.

Closely tied to this is the study of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Alexandra Adler examined victims after the fire and studied how the disaster caused anxiety and depression. This information was used during World War II to develop treatments for shell-shocked soldiers.

If you or someone you know needs help with mental health, please contact the Crisis Text Line by texting HOME to 741741, call the National Alliance on Mental Illness helpline at 1-800-950-NAMI (6264), or visit the National Institute of Mental Health website.

The owner of Cocoanut Grove was convicted of manslaughter

Naturally, there was immense public outrage over the fire, which led to criminal charges. "Crimes of the Centuries" explains that in the court proceedings, the grand jury levied indictments on 10 people, including owner Barney Welansky, his brother, a wine steward, and the manager on the evening of the disaster. Fire department personnel, administrators, and building officials were charged with negligence for the failure to inspect and perform duties. Even the architect and designer were both levied charges of conspiracy to violate building codes.

The court proceedings featured 130 witnesses. In the end, only Welansky was convicted of 19 counts of manslaughter. He was sentenced to up to 15 years but was pardoned in November 1946 by Governor Maurice Tobin after Welansky had contracted cancer. He would die shortly after.

Tobin was the mayor of Boston at the time of the fire. But Welansky and Tobin had a relationship. An electrician testified that Welansky claimed he could skirt fire codes since "Mayor Tobin and I fit." Later witnesses claimed that Welansky had stated, "They owe me plenty."

Fire codes changed and were enforced

Interestingly, there is a perception that prior to the Cocoanut Grove fire, building codes were in shambles. At the time, the National Fire Protection Association already had codes and had even gone so far as to condemn revolving doors. But there was an enforcement issue. Surprisingly, an NFPA Case Study reported that a mere eight days before the fire, inspectors had found no serious violations of the fire code.

The result of the fire was that governments took the implementation and enforcement of those codes far more seriously. Massachusetts, in fact, created a Massachusetts Board of Fire Regulations to apply strict adherence to rules and regulations. Author Stephanie Schorow commented in her book, "Thus, the legacy of the Cocoanut Grove fire for national and safety codes was, in large part, centered on civic consciousness and renewed commitment to safety; the fire made lawmakers more willing to adopt national recommendations."

New rules required better exit strategies

Aside from increased militancy in enforcement, there were important changes to fire codes made. One of the most impactful was that nightclubs became classified as places of assembly, a status they had not had before. This change put nightclubs in the same category as theaters, meaning rules and regulations would become stricter.

In addition, according to "The Fearless World of Professional Safety in the 21st Century," exterior doors started to be required to swing outward instead of inward. While revolving doors were initially banned, they were reintroduced with the requirement that there be exterior doors on the sides as an additional means of egress. Speaking of egress, this was improved by the requirement that all buildings classed for assembly had to have two separate and remote points of egress, plus a sufficient amount of emergency exits.

Furthermore, emergency lighting within a building had to be wired separately from normal lighting since Cocoanut Grove plunged into complete darkness during the inferno. The new NFPA code also called for the limitation of flammable interior decorations, like those in abundance at Cocoanut Grove. These changes undoubtedly saved countless lives over the decades since the disaster.

A Cocoanut Grove memorial is overdue

As of April 2023, it had been eight decades since the tragedy struck the heart of Boston in 1942. There have been repeated calls over the decade for a fitting memorial for the victims. The Cocoanut Grove Memorial Committee, founded in 2015, has led the most recent efforts to create a monument. It seems that this effort might finally bear fruit. In 2022, Boston.com reported that the city has been working with the committee. The group is in the process of reviewing designs for the memorial and the project is officially in the contracting phase.

Perhaps this will be the final act that will bring decades of trauma to final closure. Boston25 News reported the mayor of Boston, Michelle Wu stated, "Not only will this memorial uplift the memories of all those lives we lost and the first responders who rushed to the scene, it will remind us of what we as a city have always done in moments of great sorrow and struggle — we come together, we unite as a community.

[Featured image by Tomtheman5 via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled | CC2.5]