The Most Controversial Comic Strip Moments In History

Comic strips, or "the funnies," were considered an integral part of a newspaper's appeal for generations. Indeed, the characters that starred in them — such as Garfield the cat, Snoopy the dog, and Dennis the Menace — are all instantly recognizable to modern audiences.

But as The Week argued in 2015, comics themselves aren't as impactful as they once were. Robbed of the common audience of millions of newspaper subscribers reading the strip on the same day, comics have tended to become less topical and more formulaic in their approach. Today, most comic strips are more suitable for being binged in online archives or coffee table anthologies.

Yet comic strips and the cartoonists behind them have been known to cause controversy down the years. From career-destroying outbursts to strips that outraged readers, and from lawsuits to strips that just haven't stood the test of time, comics have had their moments in history, to the delight or outrage of their readers.

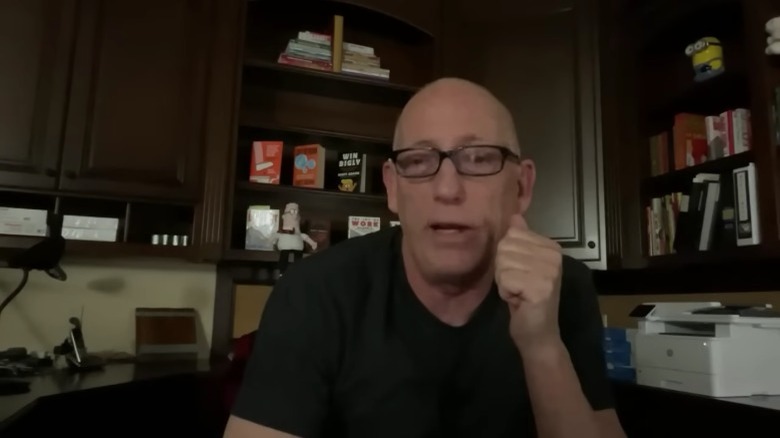

The downfall of Dilbert

The comic strip "Dilbert" has been a constant presence in hundreds of newspapers across the world since being acquired by United Features Syndicate in 1989, finding millions of fans thanks to its witty take on the absurdities and drudgeries of the corporate world and office life. Though its creator, Scott Adams, reportedly had to keep working at his office job for the first six years of Dilbert's existence, it eventually made him a fortune.

But all that came crumbling down in 2023, when Adams made some jaw-dropping comments on his YouTube show "Real Coffee with Scott Adams" that effectively ended his career as a cartoonist. In February of that year Adams was responding to a recent opinion poll in which 53% of Black respondents said they approved of the phrase "It's okay to be white." The phrase has historically had a long association with white supremacy movements. Scott went on to describe Black people who did not agree with the phrase as a "hate group," and advised white listeners to "get the hell away" from them, effectively promoting segregation.

Adams' publishers were quick to act and distanced themselves from Adams' incendiary statements by pulling "Dilbert" from hundreds of newspapers. Adams is yet to apologize for his comments and instead took to his show to dismiss his comments as hyperbole.

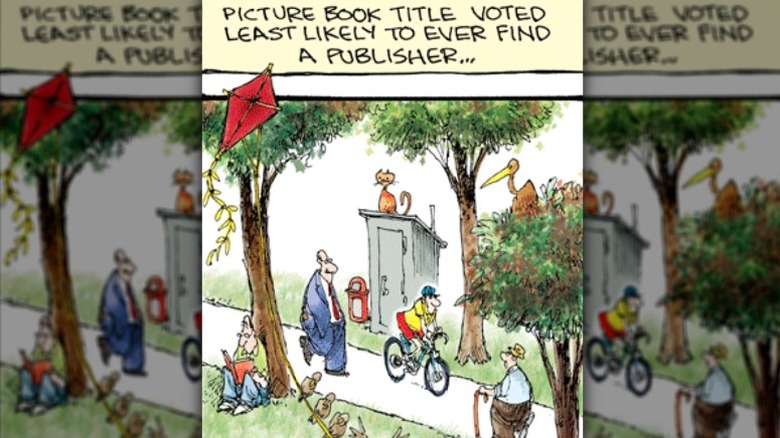

Two Non Sequitur incidents

"Non Sequitur" has been one of the most instantly successful new comics of the last decade, with its creator, Wiley Miller, also known simply as Wiley, earning a Ruben Award for Outstanding Cartoonist of the Year in 2013, the year that "Non Sequitur" was first syndicated. With the strip earning another four awards from the National Cartoonists Society, it soon grew to be syndicated in more than 700 publications.

However, Wiley's work was not without its controversies. In 2010, a comic showing a bustling park captioned "Picture book title voted least likely to ever find a publisher ... 'Where's Muhammad?'" was pulled from several newspapers after editorial fears that it would antagonize Muslim readers. "[T]he irony of editors being afraid to run even such a tame cartoon as this that satirizes the blinding fear in media regarding anything surrounding Islam sadly speaks for itself," creator Wiley Miller told The Daily Cartoonist. "Indeed, the terrorists have won."

In another incident in 2019, "Non Sequitur" was discontinued in one Pennsylvania newspaper after its publisher discovered that Wiley had hidden an "easter egg" in one of his comic strips: a scrawled message which, when read correctly, said, "We fondly say go f*** yourself to Trump."

Pogo was too political

It isn't unusual for modern comic strips to carry a political slant and still be accepted for publication. And arguably, the precedent for this was set by "Pogo," starring Pogo Possum, an enormously popular strip that hit its peak during the 1950s.

As the academic Eric Jarvis writes in his paper "Censorship on the Comics Page: Walt Kelly's 'Pogo' and American Political Culture in the Cold War Era," published in the journal Studies in Popular Culture, the comic was syndicated in 226 papers around the world by 1952, rising to 450 by the middle of the decade. Starring an animal cast who spoke in a Southern dialect, "Pogo" had wide appeal but also grew divisive in some corners for its wry political commentary. This came in the form of "outsider" animals guesting in the strip that were created to represent contemporary political figures. The most famous of these was Simple J. Malarky, a wildcat who worked as a cipher for Joseph R. McCarthy, the notorious senator who spearheaded the campaign against communist sympathizers during the Cold War.

Jarvis claims that such representations were met with strong resistance by many newspaper editors whose publications didn't chime with "Pogo" creator Walt Kelly's liberal politics. Sometimes they would alter his strips or remove "Pogo" altogether. In response to threats that the comic would be dropped should Kelly present a likeness of McCarthy in his strip again, he drew Malarky wearing a klan hood. Jarvis notes that Kelly was also critical of the USSR, but such strips tended to remain uncensored.

Little Orphan Annie's rampant Hooverism

The adventures of red-haired "Little Orphan Annie," who was first seen escaping from her sadistic governesses in an impoverished orphanage, captivated American audiences after the comic strip's debut in August 1924, and remained for around half a century. Even after the death of Annie's original creator, Harold Gray in 1968, his publishers were keen to keep the strip going with new writers and artists. "Little Orphan Annie" eventually came to an end in 2010, by which time the Broadway show "Annie" and its cinematic versions had ensured the character would forever remain in the popular consciousness.

Such was the popularity of "Little Orphan Annie" that during the early years, Gray was successful in leveraging the comic strip to convince readers to provide scrap metal to the World War II munitions effort, making him something a wartime hero. However, Gray's conservative politics often came through overtly in his comic strips. As Bruce Smith describes in "The History of Little Orphan Annie," one of the more famous instances of this came in 1934, when Gray used "Little Orphan Annie" to parody the controversial ongoing Samuel Insull trial. Journalist and future senator Richard Neuberger was highly critical of Gray's parody, describing "Little Orphan Annie" as "Hooverism in the Funnies" in an article for The New Republic.

Doonesbury satirized the anti-abortion lobby

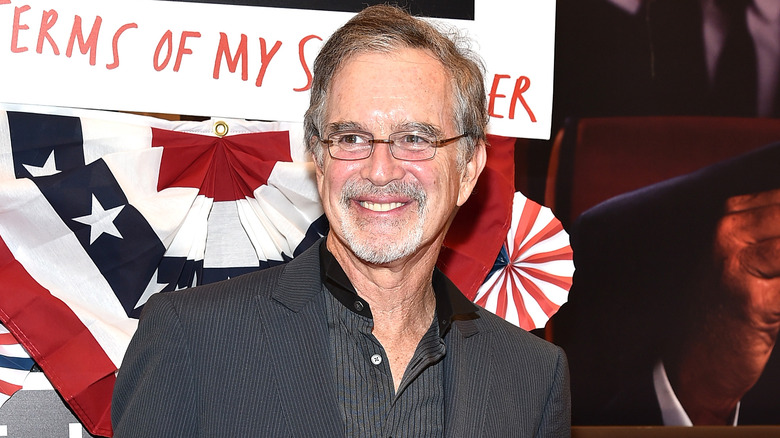

Doonesbury is one comic strip that has always worn its political leanings on its sleeve. Created by Gary Trudeau (pictured) in 1970 and incorporating elements of the counterculture of the 1960s, by 1975 "Doonesbury" was considered an essential barometer of American political feeling and was awarded the Pulitzer Prize.

The strip and its enormous cast have now been entertaining readers for more than half a century, and in that time Trudeau has not been afraid to get his hands dirty when it comes to the subjects he has been willing to tackle. But the most controversial topic Trudeau has made into "Doonesbury" material is perhaps abortion. In May 1985 six "Doonesbury" strips were withdrawn from circulation by Universal Press Syndicate. The strips in question satirized a recent anti-abortion film called "A Silent Scream," imagining a sequel: "A Silent Scream II," in which a fetus' final words are "repeal Roe vs. Wade."

Trudeau revisited the subject in 2012 in response to Republican law changes around abortion access, which led to the strip being removed from several publications, or else being moved to the editorial page by outlets willing to print it.

When The Far Side was unintentionally graphic

"The Far Side" is an instantly recognizable comic strip best known for its absurdist humor, signature single-panel design, and irresistible anthropomorphic gags about animals. Though "The Far Side" was only active for a total of 15 years — it ended in 1995 — it has remained a beloved classic in the hearts of its many fans.

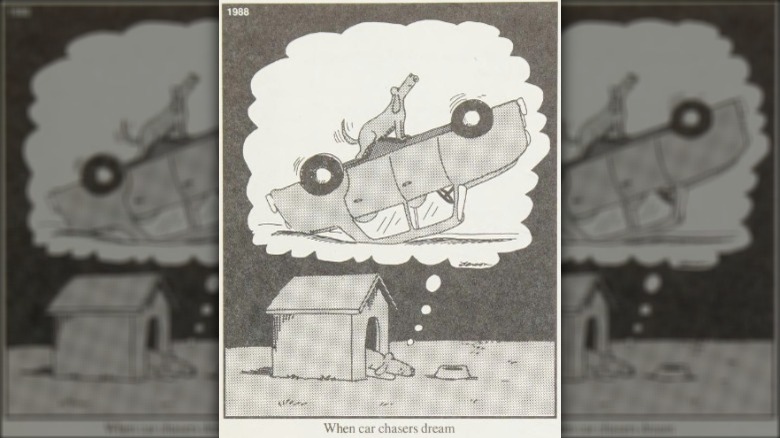

However, Gary Larson, the creator of "The Far Side," has made it clear that his career as a cartoonist hasn't always been a picnic. As he recalled in the 10th-anniversary special volume "The Prehistory of The Far Side," one strip, in particular, got him in hot water with many of his readers. In 1988, Larson drew an image of a dog asleep in a kennel, dreaming that it has finally caught up to a car it has been chasing. In a thought bubble above the sleeping dog's head, a car is flipped onto its roof, and the dog sits atop it, howling up to the sky with glee. The caption reads: "When car chasers dream."

But Larson claims that many people interpreted the panel as the dog dreaming of getting frisky with the caught car, leading to many editors rejecting the strip. From those readers who did see the published strip, Larson claims to have received many critical letters denouncing the joke as "sick." He admits that he can see how his illustration might elicit that interpretation, but that it was not intentional.

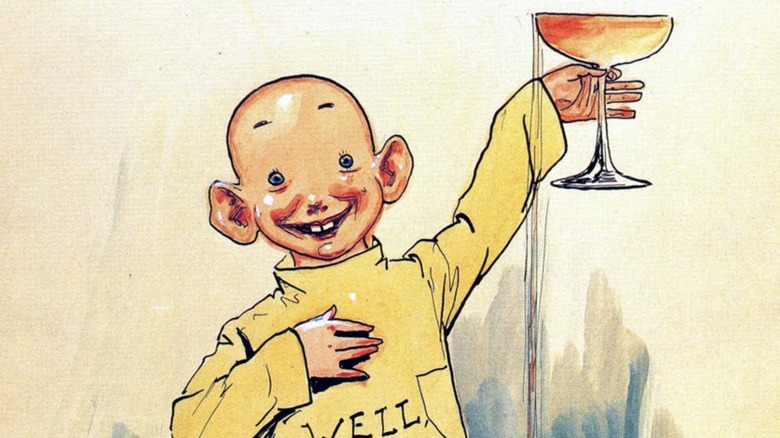

Copyright issues killed The Yellow Kid

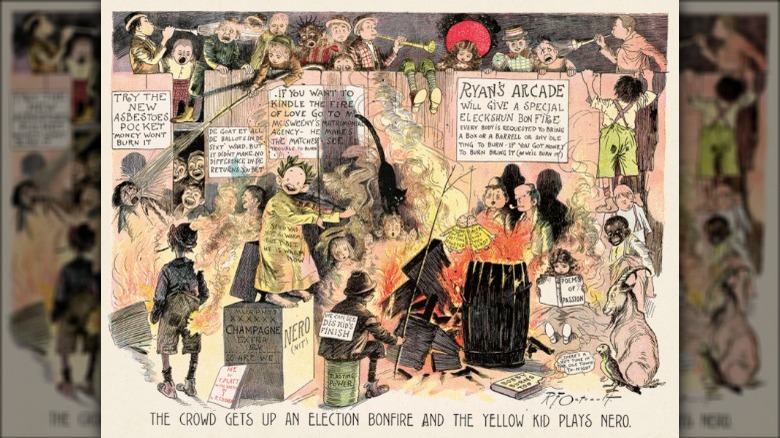

The classic comic strip featuring "The Yellow Kid" is today perhaps known as a "cartoonist's cartoon," but in the early 20th century it was a great mainstream success. The strip was created by Richard Fenton Outcault and first published in the Pulitzer-owned newspaper New York World in the 1890s. Known in the early days as "Hogan's Alley" but later named after its exuberant main character, Outcault's work was notable for showing the gritty realities of contemporary slum dwellings, focusing on the lives of street children in particular. Notably, Outcault's work frequently employed dialect.

The Yellow Kid — named for the instantly recognizable yellow nightshirt he wore — is believed to be how the comic strip wa born. The strip has also been identified as being key in popularizing comics' now-ubiquitous speech balloons.

But the 1890s were a different time, and, Outcault struggled to retain legal control over his famous creation, with the New York World also publishing its own adventures starring The Yellow Kid using a different artist named George Luk. As a result, a frustrated Outcault warned his readers in one caption: "Do Not Be Deceived None Genuine Without This Signature." However, while he applied for copyright, Brian Walker in his book "The Comics" notes that Library of Congress records show he never received approval and thus could never prevent competing comics with his character. He shortly thereafter left to work at the rival Hearst-owned New York Journal. He stopped publishing new strips featuring The Yellow Kid in 1898.

A Hustler strip that became grimly ironic

Hustler, the magazine founded by Larry Flint, isn't particularly well-known for its humor: Its chief appeal lies with the other material that it publishes. Nevertheless, even from the early days of the magazine, Hustler did publish comic strips, which of course were sexual in theme. But while Hustler continues to have an audience in the 21st century, its comic content would certainly cause an uproar were it published today.

In particular, the comic strip titled "Chester the Molester" was an ostensibly ironic strip detailing the misadventures of the titular character as he attempts to assault women and girls. Situated in Hustler, it might be argued that "Chester the Molester" was catering to the magazine's audience. However, the controversial strip spilled out into the mainstream newspapers in 1989, with the grim revelation that its creator, Dwaine B. Tinsley, had himself been charged with sexual assault against a 13-year-old girl, who was later revealed in Brian Levin's book "Most Outrageous" to be his daughter, who claimed that the abuse spanned countless incidents across a total of five years.

Though Tinsley was initially sentenced to six years in prison for the crimes, he was later acquitted on the basis that the jury in his original trial should not have been shown thousands of "Chester the Molester" strips as evidence against him.

A now-unprintable Calvin and Hobbes

"Calvin and Hobbes" has become something of a legend among comic strip fans. A fun, fantastical, but also melancholic work about childhood, imagination, and friendship, "Calvin and Hobbes" was active for just 10 years, between 1985 and 1995, before creator Bill Watterson decided to call it a day.

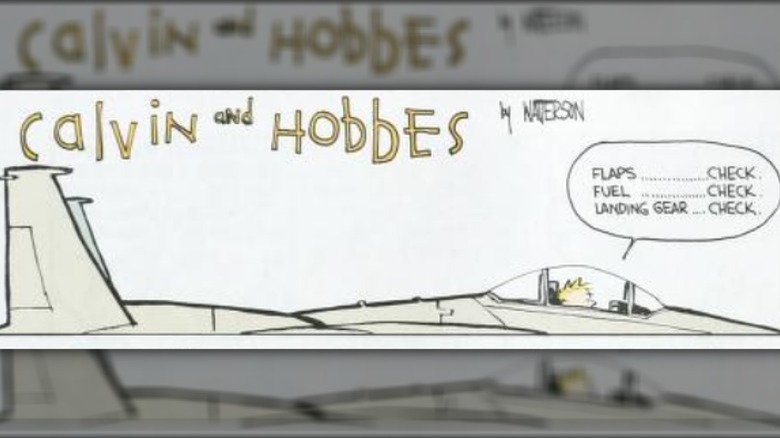

The strip is remembered fondly, but Watterson notes that his strips didn't always land well. In "The Calvin and Hobbes Tenth Anniversary Book" he discusses a certain strip featuring 6-year-old Calvin fantasizing about piloting a fighter jet and blowing up his school. Watterson recalls that he received "nasty mail" as a result, but remained defiant, arguing, "Apparently some of my readers were never kids themselves." Recent fans of "Calvin and Hobbes" have shared their shock and surprise on the internet that such a seemingly out-of-step strip was printed.

As with the entirety of "Calvin and Hobbes," the comic strip in question was syndicated years before the horrifying events of the Columbine Massacre in 1999, and prior to the perpetual incidents of school shootings that continue to plague the United States. It is doubtful that it would be published today.

The Far Side vs. Jane Goodall

If comic strips have feuds with real people, it tends to be politicians and other figures of power whose politics the cartoonist personally disagrees with or finds corrupt, pigheaded, or absurd. So it might be surprising to learn that in 1987 Gary Larson's "The Far Side" got into what appeared to have been a heated head-to-head with a rather benign target: Jane Goodall.

Goodall, a celebrated British naturalist, became famous in the 1980s for her effective activism on behalf of wild animals, especially apes, with whom she frequently bonded, as several documentaries show. In typically wry fashion, Larson, who discusses the incident in "The Prehistory of the Far Side," decided that she would make a good subject for one of his anthropomorphic strips. In 1987, he published a sketch of two apes picking fleas from each other, captioned: "Another blond hair ... Conducting more 'research' with that Jane Goodall tramp?"

The gag was enough for Larson to be served a cease-and-desist by Goodall's legal team. However, she had no idea that action had been taken on her behalf. In actuality, Goodall is a huge fan of "The Far Side," noting in the forward of the 1995 anthology "The Far Side Gallery 5" that she laughed out loud after first seeing the comic, saying "Real fame at last!"

Pearls Before Swine too-topical storyline

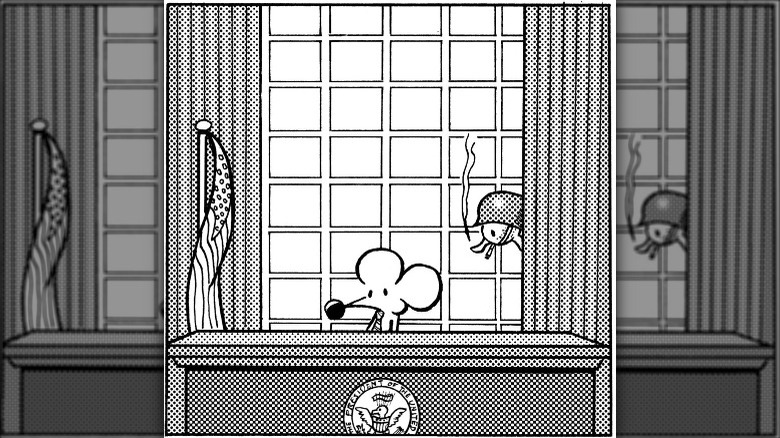

"Pearls Before Swine" is a relative newcomer compared to many of the other comic strips on this list, though it was pitched to syndicates as early as 1999. Creator Stephan Pastis had been working as a lawyer before he got the idea to submit a strip, and had never worked professionally as a cartoonist before. Nevertheless, his hilarious tales about the sharp-tongued, sociopathically ambitious Rat and his long-suffering friend Pig became a big hit. As Pastis himself admits in "Pearls Before Swine: BLTs Taste So Darn Good," this was down to industry support, most notably from "Dilbert" creator Scott Adams.

"Pearls Before Swine" has a large internet following and is syndicated in hundreds of publications around the globe. But following the events of January 6, 2021, in which Capitol Hill was stormed by a mob attempting to block the confirmation of Joe Biden's presidency, Pastis was forced to pull a storyline that was deemed too topical. In it, Guard Duck successfully orchestrates a military coup to remove Rat from the White House.

Pastis took to Twitter to announce the cancellation but explained that the seemingly topical strips were in fact written months before the events they seemed to parallel.

Gasolene Alley's centenarian cast

America's longest-running active comic strip, "Gasoline Alley" has been a constant presence in the funnies since it debuted in The Chicago Tribune way back in 1919. The invention of cartoonist Frank King, "Gasoline Alley" has successfully been handed down to younger artists over the years, who have managed to continue King's unique style and tone.

However, one unusual aspect of "Gasoline Alley" has become somewhat absurd in recent years – King's strip had a very unusual innovation right from the start. His characters aged in real-time. At the launch of the strip, the protagonist, Walter Wallet, was a young man, and as the years passed, readers saw him and his supporting cast grow older, marry, have children, and eventually die. But Wallet himself lives on as a widowed great-grandfather, defying, for now, the comic's own internal logic.