Political Cartoons That Enraged Readers

Political cartoons have offered insightful commentary on politics and public life since the early days of newspaper printing. According to the Library of Congress, the roots of the practice in the United States go all the way back to Benjamin Franklin, who foresaw their power in explaining political concepts to large audiences and convincing them of a certain way of thinking.

The cartoons themselves have also proven to be popular among readers, with cartoonists — like tabloid editors today — realizing that courting controversy is a surefire way to boost readership. For more than two centuries, political cartoonists have habitually cut close to the bone in their lampooning of politicians and other public figures — leading to some enormous outrage from offended readers along the way.

Here are some examples, from the early years of political cartooning to the present day, of cartoonists enraging either the general population or specific satirical targets.

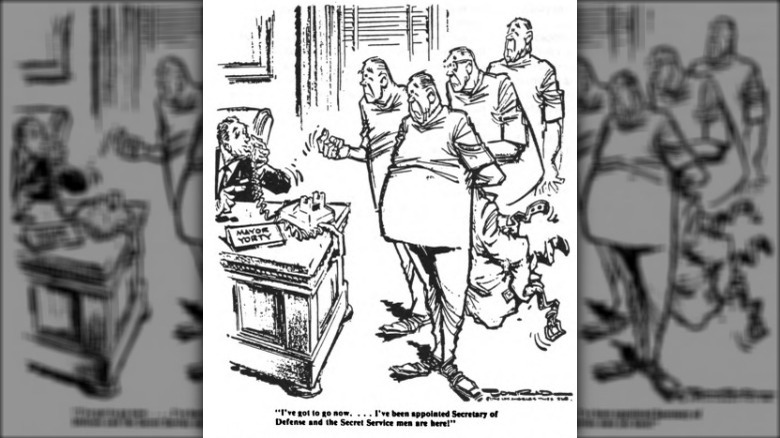

Paul Conrad's infamous LA Times cartoon

Paul Conrad was one of the most respected liberal cartoonists of the 20th century, whose decades of scathing political cartoons in The Denver Post and The Los Angeles Times won him countless fans, three Pulitzer Prizes ... and more than a few enemies. His most notable foe was President Richard M. Nixon, who famously had the cartoonist on his notorious "enemies list."

But while Conrad's tangles with Nixon may be his most famous battle, the most infamous political cartoon he drew was a 1968 piece lampooning the then-mayor of Los Angeles, Sam Yorty. The cartoon in question depicts Yorty on his phone at his desk, opposite four men, and is captioned: "I've got to go now — I've been appointed Secretary of Defense and the Secret Service men are here!" However, the four men standing opposite are actually orderlies from a mental institution who are about to put Yorty in a straightjacket.

Yorty took Conrad's editor Otis Chandler to court, claiming the cartoon was libelous in its implications for his mental health, according to Chris Lamb's "Drawn to the Extremes: The Use and Abuse of Editorial Cartoons." However, the court ruled that the satirical cartoon was not libelous since, by its nature, such works employ "rhetorical hyperbole," a phrase used in previous Supreme Court cases. The phrase has since been employed in other legal defense cases against political cartoons.

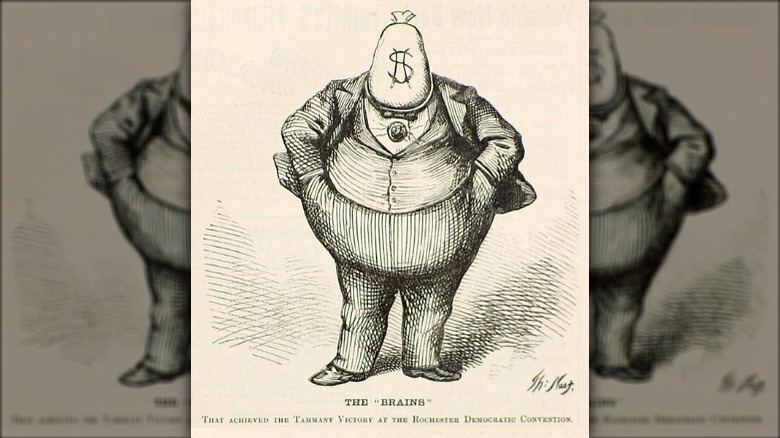

Thomas Nast vs. Boss Tweed

Political cartoonists in the 18th century didn't come any bigger than Thomas Nast, whose witty, biting, and insightful work had the power to sway the opinion of the wider public in a way editorials struggled to.

Nast's most famous campaign targeted corrupt New York politician William "Boss" Tweed, whose "Tweed Ring" of powerful political allies conspired to strip the city of funds through fraud. As described by Albert Bigelow Paine in his early biography "Th. Nast, His Period and Pictures," Nast was appalled by the crimes of the Tweed Ring, and began to vividly highlight them in a series of hard-hitting political cartoons in Harper's Weekly, the magazine at which he spent the majority of his career.

Tweed was reportedly so alarmed that Nast's cartoons were turning Tweed's constituents against him that he and his allies sent death threats to the cartoonist, tried to convince him to leave for an all-expenses-paid trip to study art in Europe, and attempted to bribe Nash to the tune of $100,000. Knowing the Ring's desperation, Nash managed to haggle his briber up to $500,000 before point-blank refusing the payoff. "I made up my mind not long ago to put some of those fellows behind bars, and I'm going to put them there!" he reportedly said. Tweed was convicted in 1873, and though he later escaped prison and fled the country, he was recaptured and died in 1878.

The New York Times' Trump, Netanyahu cartoon

As a reputable and trusted news source, The New York Times isn't often accused of publishing incendiary or offensive content. But in 2019, the newspaper was heavily criticized for a political cartoon that many found badly executed and downright discriminatory.

A critique of then-President Donald Trump's relationship with Israel's Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, the cartoon in question depicted Trump as a blind man being led by a guide dog wearing a collar featuring the Star of David, the symbol of Judaism. In the cartoon, Trump is also depicted wearing a Jewish head covering. The cartoon drew a torrent of criticism online for being antisemitic.

Days later, The New York Times published an editor's note apologizing for the cartoon, which they admitted contained "anti-Semitic tropes," blaming an "error in judgment" for its publication. The note stated that the offensive cartoon had since been deleted from the newspaper's online platforms. But the paper went further, announcing that it would cease publication of political cartoons in its international editions, a decision questioned other outlets such as The Independent.

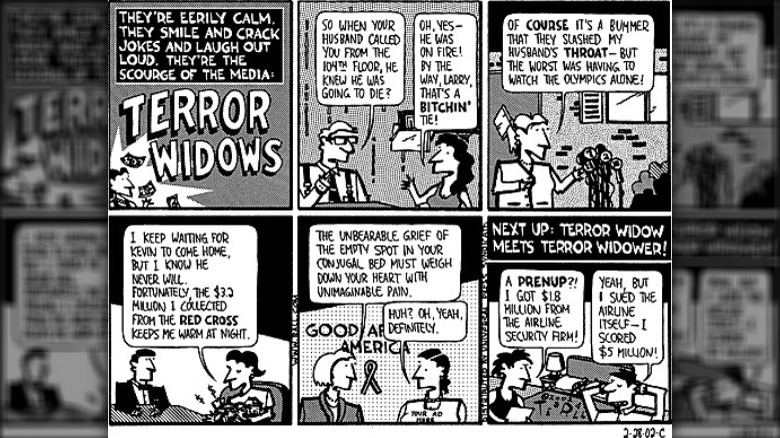

Ted Rall's badly-timed 9/11 comic

The horrifying terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, which led to the deaths of 2,996 people, undoubtedly shook the American psyche to its core. The years that followed were a sensitive time, with the subject of the attacks becoming one of the biggest taboos in public discourse.

So it's no surprise that one particular political cartoon by the cartoonist Ted Rall caused an enormous backlash when it was published in March 2002. The cartoon in question, entitled "Terror Widows," mocks the partners of those who lost their lives in the attacks, describing them as "eerily calm" and the "scourge of the media." Rall's piece also appeared to take issue with insurance payouts received by 9/11 widows, with one figure claiming that, although she lost her husband, "the $3.2 million I collected from the Red Cross keeps me warm at night."

The New York Times quickly pulled the offending cartoon from its website, as described in an article in The Nation. However, Rall was defiant when it came to offering an apology, and The American Association of American Editorial Cartoonists came to his defense, criticizing the censorship of his work in a post-9/11 media landscape that many cartoonists found stifling.

The New York Daily News' drawing of Andrew Yang as a tourist

The New York Daily News attracted a barrage of complaints in 2021 due to a political comic by cartoonist Bill Bramhall, which depicted prominent businessman Andrew Yang, who is Asian American, emerging from the subway station at Times Square, a sight that prompts a shopkeeper selling souvenir t-shirts to comment: "The tourists are back!"

The cartoon was ostensibly a comment on a debate around the authenticity of Yang as he ran for mayor of New York. Yang sought to represent himself as a true New Yorker, having been born in the city. However, critics noted that Yang often resided outside of the city, and had never voted in the city's mayoral elections before. Bramhall seemed to reference an interview with Yang in which he named Times Square, the city's tourist center, as his favorite subway stop.

Many of the cartoon's critics took issue with what they saw as Bramhall's play to racial stereotypes concerning Asian tourists in America. The Hill noted the cartoon was published at when hate crimes against Asian Americans were rising, including an attack on a man who was pushed onto the tracks in a subway station in Queens, New York. In a press conference, Yang decried the hate "tearing our city apart," and criticized the discourse around who ought to be considered a true New Yorker as unhelpful, adding: "None of us is more New York than anyone else. We all belong here."

The Washington Post's satire of Ted Cruz

In late 2015, when Ted Cruz was campaigning for the Republican presidential nomination — which he would later lose to Donald Trump — he and his team released a parody Christmas ad showing the senator reading Christmas stories to his young daughters that criticized the Democratic government under Barack Obama.

To Washington Post editorial cartoonist Ann Telnaes, the inclusion of Cruz's children in a political attack ad was in bad taste. To satirize it, she published an animated cartoon on the newspaper's website of Cruz dressed in a Santa outfit, holding an organ grinder with two small monkeys dancing in front of him. The cartoon was captioned: "Ted Cruz uses his kids as political props."

While Telnaes sought to lampoon Cruz for exploiting his children for political gain, the fact that she had transmogrified them into primates suggested to many that the cartoon was an attack on the children themselves. Telnaes' piece drew a vicious reaction from many who saw it, especially Republicans and Cruz himself, and the cartoon was withdrawn (via The Washington Post).

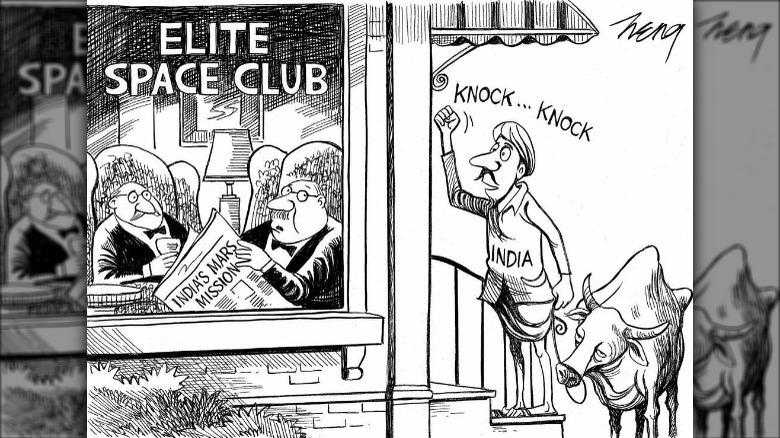

The New York Times' India comic

In 2014, India achieved a major astronomic feat: a probe launched from the Bay of Bengal in 2013 successfully entered orbit around Mars, alongside those previously launched by the United States, Europe, and Russia, according to the BBC. The country's success was greeted with wonderment by many, especially considering the fact that a country with a limited history of space travel had managed to get a probe to Mars on a comparatively minuscule $74 million budget.

In response to the Mars mission, The New York Times published a cartoon showing affluent old white men sitting in a room bearing the sign "Elite Space Club," where they read about India's Mars mission in newspapers. Outside, an Indian man in a turban and sandals knocks on the door with one hand and holds the leash of a cow in the other.

The newspaper's editor Andrew Rosenthal admitted in a statement that the comic had generated a great many complaints from angry readers, and he apologized for the offense caused, stating it "was in no way trying to impugn India, its government or its citizens." The cartoon has since entered the world of meme culture, with followers of India's continued astronomical successes remixing it time and again to revel in their defiance of the West's expectations.

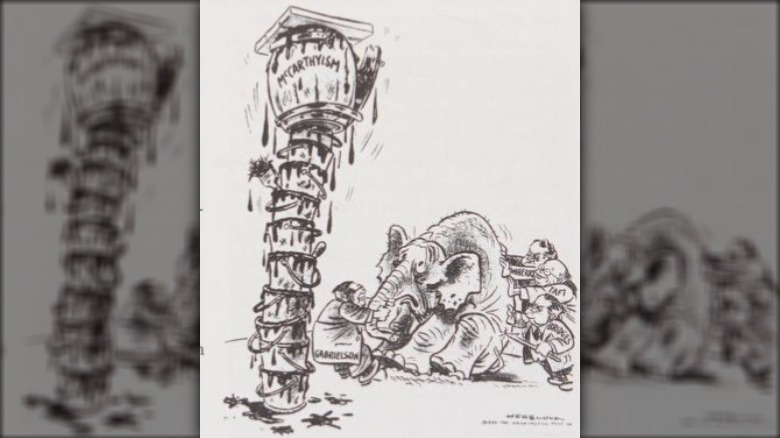

Herblock vs. McCarthy

The triple Pulitzer Award-winning cartoonist Herblock — born Herbert Lawrence Block in 1909 — was so well respected in the field of political cartoons that he was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1994. But Herblock wasn't always so beloved by the political establishment, especially during the decades that he targeted officials as an editorial cartoonist for The Washington Post.

Herblock had many recurring targets, not least Richard M. Nixon, whom he critiqued over the course of 25 years, according to Haynes Johnson and Harry Katz's biography, "Herblock." It was Herblock coined the term "McCarthyism" in his cartoons to describe the actions of Senator Joseph McCarthy, who in the 1950s orchestrated a brutal campaign to uncover communist sympathizers in American public life.

McCarthy featured regularly in Herblock's work throughout the period. His angry cartoons on the senator's attempts to quell "communist subversion" drew the ire of McCarthy's multitudes of supporters, who would occasionally visit Herblock at the offices of The Washington Post to have it out with him face-to-face. Elsewhere, McCarthy himself tried to pressure the State Department to drop funding to have a pamphlet, "Herblock Looks at Communism," printed and distributed.

Herblock himself was widely accused of being a communist because of his criticisms of Nixon and McCarthy, though his biographers argue that he was a true patriot, whose love for his country underpinned the bite in his cartoons.

Zapiro and Zuma's ongoing feud

The political cartoonist Jonathan Shapiro, better known by his alias Zapiro, has gained notoriety in his native South Africa for his brutal takedowns of public figures. Arguably, his fiercest feud has been with African National Congress leader Jacob Zuma, whom Zapiro took to portraying with a shower cap on his head, alluding to comments by Zuma that the HIV virus could be kept at bay by taking a shower.

In 2008, Zuma took Zapiro to court over a cartoon that depicted Zuma's supporters holding down a woman personified as the "Justice System," while Zuma himself stands over her, pants unbuckled, preparing to rape her. The cartoon provoked a huge amount of controversy, which its creator seemed to have partially anticipated. Speaking to the South African Mail & Guardian, he said, "When the idea popped into my head, I thought it was too heavy ... But, later I reversed this thought. I thought, this is exactly what I want to say."

Zuma has long been a controversial figure in South Africa and beyond. The graphic cartoon also makes reference to accusations that Zuma had raped a family friend, charges that were dismissed. Zuma himself dropped his legal action against Zapiro.

If you or anyone you know has been a victim of sexual assault, help is available. Visit the Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network website or contact RAINN's National Helpline at 1-800-656-HOPE (4673).

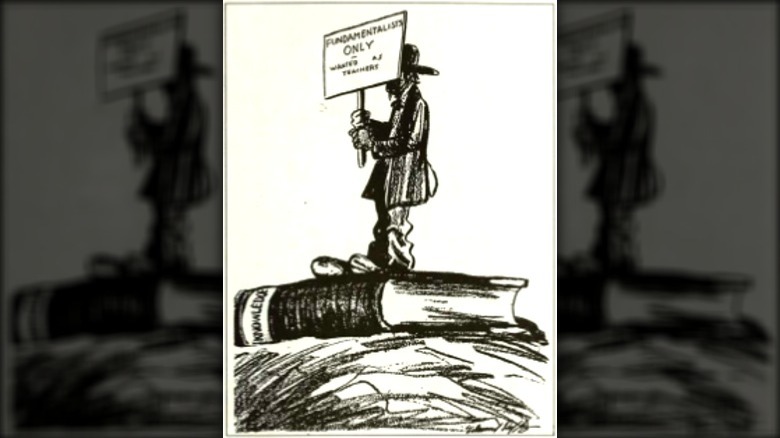

Edmund Duffy's targeting of Tennessee creationists

In July 1925, a Tennessee teacher named John T. Scopes was put on trial for teaching Charles Darwin's theory of evolution to students in Tennessee schools. His lessons allegedly violated the state's Butler Act, which outlawed instruction denying the creation of man by God.

Though the trial was put into motion by Scopes' supporters as a way of legally challenging the backward-thinking Butler Act, what became known as the "Scopes Monkey Trial" and later the "Great Monkey Trial" divided newspaper readers and inflamed tensions between evolutionists and creationists who supported the Butler Act.

The controversy was furthered by Baltimore Sun cartoonist Edmund Duffy, who had previously made a splash with vivid and disturbing cartoons showing the reality of lynchings orchestrated by the Klu Klux Klan. Under the stewardship of his wild and unorthodox editor H. L. Mencken, who penned incendiary editorials about the trial and the people of Tennessee, Duffy created a series of cartoons that reportedly offended readers so much that the Baltimore Chamber of Commerce warned that their continued publication would damage the economy.

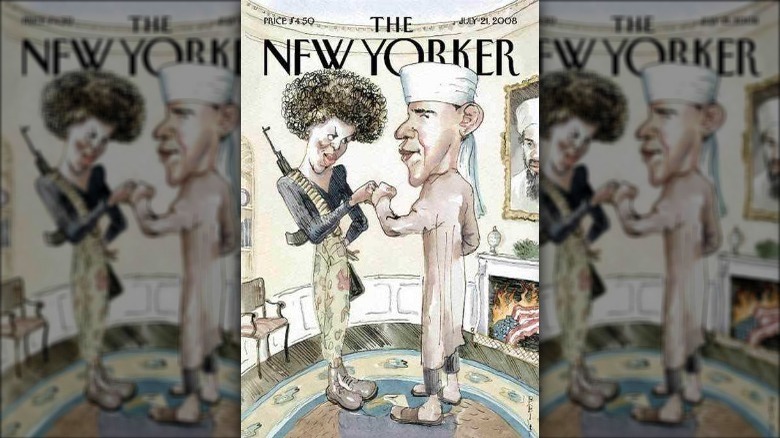

The New Yorker's drawing of Obama as a terrorist

The liberal, left-leaning New Yorker is a publication that embraces tradition with pride. Since the publication of its first issue in 1925, the magazine has purposefully maintained its penchant for elegant and flowery prose, vintage typography, and a consistently light editorial position.

In 2008, however, the magazine seemed to turn on a dime, transforming into a heavy-handed tabloid with its July 21 cover, which featured an image of Barack and Michelle Obama bumping fists in the Oval Office, he dressed in traditional Muslim clothing, and her in army fatigues carrying a machine gun. To top it off, the stars and stripes are shown burning in the fireplace and a portrait of Osama bin Laden hangs on the wall.

The cartoon was intended to be a satire of Republican attacks on Obama, according to the BBC. A statement from The New Yorker says it "combines a number of fantastical images" painted by the right-wing press, which at one point accused Obama of being a radical Muslim sympathetic to terrorists. However, the cartoon drew condemnation from across the political spectrum and from the Obamas themselves, whose spokesman deemed it "tasteless and offensive."

Jyllands-Posten's Muhammad cartoon compendium

In 2005, the Danish newspaper Jyllands-Posten ran a full-page feature containing 12 cartoons of Muhammad. The move was an intentional provocation: Islam forbids the creation and reproduction of images of the prophet. As outlined by The New York Times, the publication occurred in the mid-2000s against the backdrop of anxieties about the immigration of a large Muslim population to Europe, which saw many European countries lurch to the right.

Editorials at the time explained the stunt was meant as a challenge to that specific Islamic rule, which editors and cartoonists said was incompatible with the concept of the freedom of the press, highly prized in countries such as Denmark. The cartoons were published in solidarity by several other European publications.

The fallout from the cartoons was enormous. Within weeks, masked gunmen had intimidated staff at the offices of the European Union in the Gaza Strip, Danish goods had been boycotted, the offices of the offending newspaper were threatened with bomb attacks, Danish embassies were bombed, and protests were held around the globe, resulting in hundreds of deaths worldwide.

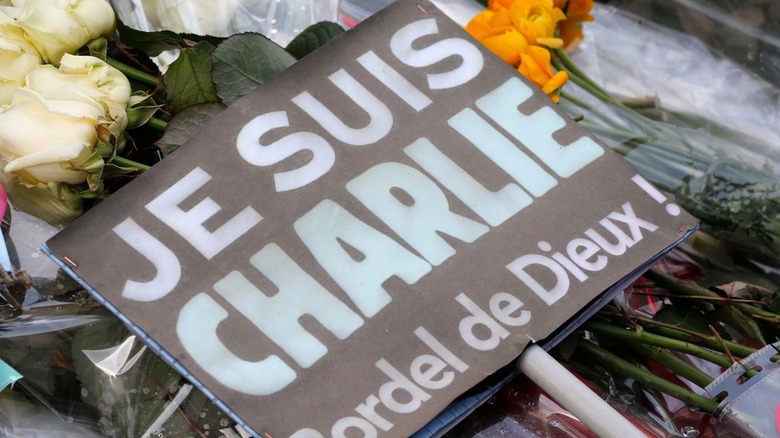

The deadly Charlie Hebdo attack

Ten years after the publication of cartoons of the Prophet Muhammad, Europe once again found itself in the grip of a political cartoon controversy that would have deadly consequences, with a shocking attack on the offices of the satirical French magazine Charlie Hebdo that left 12 cartoonists and journalists dead.

As described by CBC, the 2015 shooting was revenge for the magazine's continuous publication of images of Muhammad in contravention of Islamic law. The atrocity occurred against a backdrop of racial tensions within France, with anxieties about Muslim immigration spurring support for far-right political parties. Soon after, Parisian schoolteacher Samuel Paty was decapitated by a teenage attacker after he reportedly showed the Charlie Hebdo cartoons in class.

After an investigation into what the French government described as "Islamist separatism" in 2020, French courts convicted 14 people in connection with the terror network responsible for the attack on the offices of Charlie Hebdo. As the trial opened, the magazine once again reprinted the offending cartoons.