Clyde Barrow Almost Had A Completely Opposite Life

The stolen car bumped its way down the rural road outside of Sailes, Louisiana. It was before dawn on May 23, 1934. Next to the road, law enforcement officers from Texas and Louisiana under the command of Frank Hamer, a retired Texas Ranger, hid in the bushes, waiting. When the car, a tan Ford V8, appeared, the officers let loose a volley of bullets — 107 rounds — that killed the occupants, the notorious bank robbers Bonnie Parker and Clyde Barrow.

Dr. James L. Wade's autopsy report on Barrow — which he wrote later that day — mentions a tattoo on the inside of Clyde's left arm. The anchor and shield design included the initials "U.S.N." It was a U.S. Navy tattoo. But Barrow had never been in the Navy. So why did he have someone use indelible ink to permanently mark his body with this particular design? And how would his life have changed if this legendary criminal had instead become an unknown seaman?

Born into a poor farming family

Clyde Chestnut Barrow was born on March 24, 1909, the fifth of seven children of Henry and Cumie Walker Barrow, poor tenant cotton farmers in rural Telico, Texas. His mother would later recall that as a child Clyde was "a good boy, playful and full of life," via "Bonnie and Clyde: The Making of a Legend." Although, he did love to pretend he was the infamous Wild West outlaw, Jesse James, learned to use a gun, and was known as a good shot. The family was poor and the children had little to eat and had to sleep on makeshift beds in the tiny three-room home.

By the time he was a teenager, Clyde stood just under 5-foot-6 inches and weighed in at around 125 pounds, possibly related to his meager diet growing up. He left school at 16 and the next year decided to join the U.S. Navy., but it was not to be.

A Navy man

In a photograph dated 1925, Clyde Barrow stands next to his sister, Nellie Barrow. He's wearing what appears to be a Navy uniform with a medal pinned to his chest. He was 16 and couldn't legally join the service until the next year. He looks into the camera with a slight smile on his face, and it's obvious that he's enjoying playing dress-up. He even went and got a naval tattoo in preparation for what he assumed would be his career.

By then the family was living in West Dallas, and the various factory jobs the teenager had held down didn't satisfy him. The military offered a way for a young man of little means to advance up the social ladder. But the Navy rejected Barrow based on the after-effects of a childhood illness. With that avenue of advancement blocked, Barrow found another way to make it in the world.

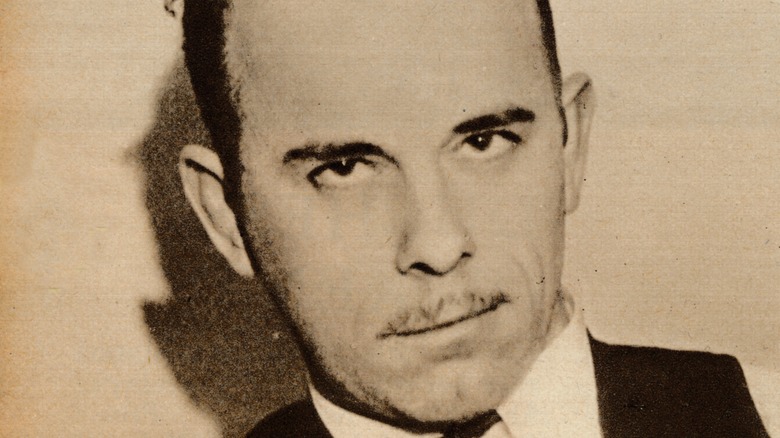

John Dillinger

It's always interesting to imagine how someone's life might have turned out if they had taken another path. One that historians often point to is Adolph Hitler's failed attempt to get into art school. But in the case of Clyde Barrow, we have the benefit of looking at the life of another iconic criminal of the same period who actually served in the U.S. Navy before beginning his infamous career as a bank robber: John Dillinger.

Dillenger joined the Navy in 1923 to avoid charges for stealing a car in Indiana. He served on the battleship U.S.S. Utah as a fireman, third class, for a total of 22 days before he went AWOL for the first time. After less than a year, the Navy dishonorably discharged him. For some, the rigors of the military and its hierarchical and rigid framework just don't work. If, like Dillenger, the Navy hadn't changed Barrow's particular criminal arc, how about his other passion?

Clyde Barrow, musician?

Besides his apparent love for the Navy, Clyde Barrow's other passion was music. He taught himself to play the guitar as a child. "He liked music better than anything," his mother recalled, per "Bonnie and Clyde: The Making of a Legend." "His first ambition was to be in some kind of a band with other boys." He also loved to dance the Charleston. In West Dallas, Barrow's brother-in-law taught him how to play the saxophone, and Barrow often played guitar and sang for his friends. But music wasn't lucrative. By the time Barrow was 20, he'd already racked up a number of crimes under the influence of his older brother, Buck.

Bonnie Parker, who Barrow met in 1930, might have been a poet — she often sent her poems to the press while they were on the run from the law — or an actress. She performed in school plays and sang in talent shows when she was younger. Instead, when the two got together, all hell broke loose. They left a trail of bodies in their wake from February 1932, when Texas paroled Barrow, until May 1934, when law enforcement officers gunned the couple down in Louisiana.

The life he chose

By the time they met their deaths on a rural road in Louisiana, Bonnie Parker and Clyde Barrow were blamed for murdering 13 people, nine of them lawmen. The couple, with a rotating crew that included Buck Barrow and one of Clyde's childhood friends, blasted and robbed their way across five states, from New Mexico to Missouri.

Even while committing murders, kidnappings, and holding up banks and stores, Barrow continued to enjoy playing music. On several occasions, the police found Barrow's guitars that he'd been forced to leave behind while escaping from the law. In one instance, he cheekily got his mother to ask for the instrument back from the police, who refused. Inside the Ford in which Barrow died, the police found a saxophone, along with a huge cache of guns. It was too bad for both Barrow and his victims that the Navy rejected him and that his music career never took off.