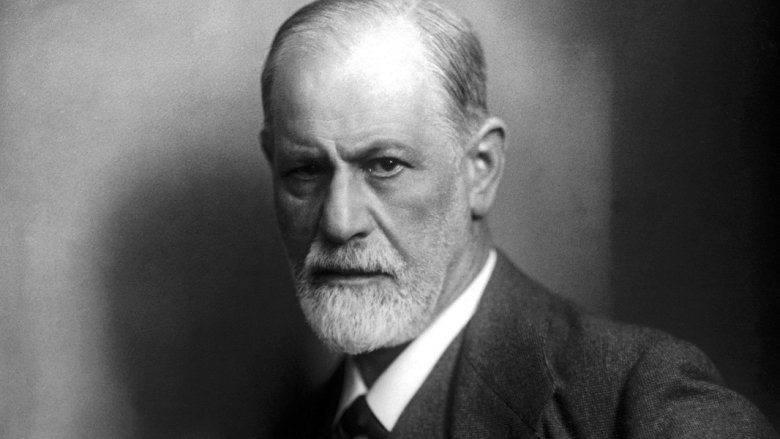

The Freaky Truth About Sigmund Freud

In 2018, a woman named Kathy McVay attended a baseball game and got whacked between the eyes by a hot dog shot from a cannon. In her words, "It just came out of nowhere. And hard." If Sigmund Freud had been alive to analyze that, he probably would have called it a subconscious simulation of intercourse. Not because it made sense, but because his brain was pretty deep in the gutter.

Throughout his life Freud consistently bucked convention. Born in 1856 to a Jewish family, he rejected religion and placed his faith in science. He spent most of his life in Vienna, Austria, where prevailing attitudes toward Jews constrained his main career options to doctoring or lawyering. He opted for medicine but considered the prospect of practicing it "slightly repugnant," per PBS. So he converted his aversion into innovation. Freud trained to treat hysteria with hypnosis but eventually developed a new approach. He had patients relax and relate their thoughts in a stream of free associations. Between those interactions and his introspections, he invented psychoanalysis.

During the early 1900s Freud began rattling off ideas that rattled the public, including the theory that babies have carnal impulses. He also pushed pioneering notions about the subconscious and told his friends and family to take cocaine. Today many people dismiss Sigmund Freud as a creepy cokehead who pulled nonsense out of his associations. But he was a captivating cokehead with an outlandish life story.

Freud's blown job

Freud could insert a wiener into any situation because he saw them everywhere. He claimed "all elongated objects" that pop up in dreams "represent the male member." Fittingly, his first huge breakthrough in dream interpretation arguably occurred because he compared noses to flesh hoses. According to medical journal JRSM, he made that connection thanks to his friend and physician Wilhelm Fliess. Fliess thought noses were neurologically linked to people's privates. Freud found the notion cogent because he saw similarities between nasal tissue and a male's excited blood sausage.

This spelled calamity for Emma Eckstein, a patient who Freud felt pleasured herself excessively, per the Guardian. In 1895 he tried to cure Eckstein by having Fliess remove a bone from her nose. She spurted blood like a geyser for days before a doctor discovered the cause. Freud recalled in a letter that Fliess had left "at least half a meter of gauze" inside Eckstein's face. Once it was removed, a "flood of blood" gushed from her nasal cavity, and her pulse temporarily stopped. She bled intermittently for months, and according to medical historian Howard Markel, the surgery mangled her face and caused a life-threatening infection.

Freud "felt sick" about the incident and had a harrowing nightmare he named "Irma's injection." Biographer Peter Gay observed that it served as the first dream Freud ever systematically examined. He concluded that he subconsciously wanted to mitigate guilty feelings, inspiring the theory that dreams symbolically fulfill wishes.

Freud's nasal fixation

Freud's interest in noses wasn't restricted to those of his patients. Around the same time he arranged for Fliess to rearrange Emma Eckstein's face, he also had work done on his own nose. As the New York Times described, Freud had chest pain and migraines, and his nose oozed "ample amounts of pus." He hoped Fliess could alleviate all of it by slicing into his sniffer. But the plan blew up in Freud's face like upside-down nostrils.

Freud's issues were nose-related. But surgery couldn't fix them because they stemmed from a nasal fixation. He had been hooked on cocaine for over a decade, and his body was beginning to buckle. Medical historian Howard Markel explained that Freud began dabbling in cocaine in 1884 in hopes of helping his pal Ernst von Fleischl-Marxow kick a morphine habit. Instead, Fleischl-Marxow kicked the bucket after developing a serious coke dependency in addition to his morphine addiction. Unfortunately, Freud didn't appreciate the danger because he held cocaine in high regard. He recommended it as medicine and praised it for improving his mood and aiding in his analyses.

During the mid-1890s Freud's health declined, and he had Wilhelm Fliess cauterize regions of his nasal cavity. To his dismay he found "thick, old pus in large clots" the next day. Even so, his drug use continued, and Fliess encouraged it. Freud's dependency grew and grew until he purportedly quit in 1896.

The marriage canceller

During his cocaine phase Freud directly wrecked at least two lives. That's the opposite of a doctor's duty, but at least those tragedies were accidents. When Freud destroyed Horace Frink's marriage, however, it was totally intentional. Per the LA Times, Frink was an American surgeon who put down his scalpel to study psychoanalysis in 1909. He also grappled with depression and later went to Vienna for Freud's help.

According to the New York Times, Freud diagnosed Frink with repressed homosexuality and advised him to seek a new wife. Not just any new wife, but a millionaire heiress who already had a husband and also happened to be Frink's patient. After Frink left Vienna in 1921, Freud selected him to lead the New York Psychoanalytic Society. In other words, he personally appointed a patient to an important position while pressuring him to make an exceedingly unethical and life-altering decision.

It gets sleazier. Frink apparently didn't think he liked ding-a-lings, prompting Freud to tell him, ”Your complaint that you cannot grasp your homosexuality implies that you are not yet aware of your phantasy of making me a rich man." Freud basically acknowledged he wanted money from Frink once he ditched his wife and wed his wealthy patient. He also personally urged the heiress to leave her husband and marry Frink. And it worked ... but not for long. Frink's first wife died soon after they split and Frink went insane, driving his wealthy new wife to divorce him.

Anna Freud's beat-and-meet

Maybe Freud saw wieners everywhere because he was one. If so, that could explain why he the screwed with the lives of Horace Frink and his wives, and arguably the life of Frink's daughter, who witnessed her dad's divorces and mental decline. Or maybe Freud was just a terrible therapist. Who knows? Emma Eckstein's nose, probably. But not all of Freud's patients had such traumatic experiences. His daughter Anna, for example, just had really weird ones.

As Psychology Today detailed, Freud psychoanalyzed Anna in 1918 and 1924 because she purportedly tickled her lady pickle too much. This particularly troubled Freud because he considered DIY lovemaking a masculine activity. Determined to make her more ladylike, Freud spent years discussing Anna's past. As it turned out, around age 6 she began having what she called "beating fantasies." She pictured herself as a man who'd been tied up by a knight. The fantasies reached their peak when the knight brutally beat the man for refusing to tell "family secrets."

Anna was 23 when she revealed these thoughts to her father. That's super weird — especially since Freud learned people's family secrets for a living and believed patient-therapist interactions were inherently erotic. Anna didn't seem bothered, though. She grew deeply attached to her daddy (to the point that it disturbed him) and later became a renowned psychoanalyst. Freud, meanwhile, updated his ideas on male envy after dissecting his daughter's fantasies.

The Oedipus link

Sigmund Freud's idea of a "your mom" joke was probably, "My mom is so hot — oh wait, I slipped up." That's just how he rolled: in the hay with the mother of his dreams. No, really, he dreamed about his mom. Per PBS, as a boy Freud had a nightmare about "beloved mother with a peculiarly calm, sleeping, facial expression being carried into the room by [people] with bird beaks." He awoke weeping and wailing and then woke up his parents. According to clinical psychologist Martin Bergman, that jarring imagery followed Freud his whole life. It also guided his life's work.

Freud believed the key to deciphering the beak sequence was the word "vogeln," which means "birds" in German but also crudely alludes to the birds and the bees. His nightmare contained bird-like people and furthermore featured the word for bird. Freud construed the imagery as a Hitchcock horror scene without the "Hitch." However, the Oedipus complex wasn't truly born until after Freud's father died in 1896.

According to PBS, Freud briefly believed one of his dreams suggested that his dad molested him and some of his siblings. But he abandoned that avenue and remembered how as a boy he competed with his father for his mother's love. He soon believed that every boy dreams of marrying his mother and consummating the marriage, creating animosity toward the father. However, Freud admitted to having to convince patients that their seemingly meaningless dreams masked Oedipal urges.

Freud's massive heart-on

It's easy to see Freud as a lewd dude who pursued taboo obsessions through sham psychology. But his original impetus was marriage. PBS pointed out that Freud initially wished to become a scientist. He wanted to do lab research, not search for the roots of neuroses. However, at age 26 he met Martha Bernays and became utterly smitten. Freud treated Martha like a queen (presumably Jocasta). He romanced her with roses, lavished with love letters, and wooed her with nose candy.

Freud fell for Martha around the same time he started tinkering with cocaine, and according to the Guardian, he excitedly sent her packets of the stuff. He even combined his two passions, Martha and coke, in an 1888 love note. Per NPR, he wrote: "When I come, I will kiss you quite red and feed you until you are plump. And if you are forward, you should see who is the stronger — a gentle little girl who doesn't eat enough, or a big wild man who has cocaine in his body."

Sadly, it wasn't all sunshine and snorting. Freud was a possessive partner who barred Martha from ice skating because he didn't want her locking arms with a male skater. He also didn't trust her around artists, who Freud feared could easily seduce her. Plus, he was broke. Lab work wasn't lucrative, and Freud couldn't provide for a wife. So he became a doctor in order to become Martha's husband.

Like a hump on a log

For Martha Freud cocaine smelled like happiness, but she thought psychoanalysis stunk. According to the Guardian, she regarded it as smutty entertainment. Perhaps it was. Freud and Martha didn't knock boots often. And after having their sixth child Martha basically stopped wearing boots. In personal letters Freud acknowledged "living in abstinence" at times. Then again, some scholars suggest Freud found relief with his sister-in-law.

Historians have long speculated that Freud and his wife's sister, Minna Bernays, performed the nocturnal Viennese waltz together. The New York Times reported that the first hanky-panky claim came from Freud's former pupil and later opponent Carl Jung. Jung said a sobbing Bernays confided in him in 1907, confessing that she and Freud played doctor. Jung later implied Freud impregnated her. However, since he seemingly had an ax to grind, few people believed him.

Die-hard Freud fans have a hard time believing that the man who ruined two marriages would cheat on his wife. Biographer Peter Gay noted that letters between Freud and Bernays suggest a special closeness, but nothing overtly inappropriate. Freud shared some of his marital woes with her, but not necessarily his marital bed. However, some historians cite a two-week trip Freud and Bernays took to the Swiss Alps. They stayed at a hotel honeymoon suite, and Bernays was listed as Freud's wife in the hotel log book. Researchers drew naughty conclusions, which author Albrecht Hirschmüller painted as "premature" conjectures.

Napoleon gyno might

Freud's life now sounds sort of sordid, but it didn't before the mid-1980s. Up to that point official biographies largely lionized the psychoanalyst and downplayed his downsides. But partly thanks to Freud's patient, protégé, and personal friend Princess Marie Bonaparte (above), people know the darker parts of his existence.

The New York Times described her as "an unlikely analyst." The great-grandniece of Napoleon, Bonaparte had an unfulfilling love life. She married a Greek prince who was in love with his own uncle, had string of disappointing mates, and wanted to mate with her equally eager son. She was the perfect patient for Freud, who discouraged bedroom-based mother-son bonding. But he encouraged her to become a psychoanalyst, and they became buddies.

In 1936 Bonaparte purchased a bunch of Freud's personal letters from a bookseller, per the New York Times. Those writings spanned 17 years, and when they were finally published in the 1980s, they revealed many of Freud's flaws. They proved he used cocaine for roughly a dozen years instead of three like people used to think. Freud confessed to falling asleep during sessions with patients. There's even evidence that he "borrowed" multiple theories from his physician Wilhelm Fliess.

Bonaparte didn't just save Freud's embarrassing admissions; she saved his life. As The Atlantic elaborated, in 1938 the Nazis took over Austria and started persecuting Jews. They detained Anna Freud and burned her father's books. Bonaparte lobbied for Anna's release and helped Freud's family escape.

The hate escape

1938 was an intensely terrifying time for Freud. He faced advanced jaw cancer and advancing Nazis, and the Nazis were metastasizing quickly. Doom loomed as the Gestapo rounded up Jews, and Freud was targeted due to his ancestry and the salacious nature of his work. Marie Bonaparte did her best to help him, but the outlook looked awful once Freud was assigned a Nazi overseer whose job was to annex his assets. Fortunately, serendipity intervened.

As psychologist Michael Cohen detailed, Freud got paired with Dr. Anton Sauerwald, "a chemist whose hobbies included bomb-making and gardening." As a Nazi, he knew he was supposed to rob Freud. But as a scientist whose professor knew Freud personally, he felt compelled to read his writings first. Sauerwald was floored by Freud's intellect and elected to help him abscond to London. He concealed Freud's foreign bank accounts and assisted him in obtaining visas for 16 relatives and friends. Furthermore, he persuaded the Gestapo to send many of Freud's belongings to England.

Sauerwald even visited Freud in London and purportedly helped him obtain medical treatment. Nevertheless, he didn't fully renounced Nazism. Author Mark Edmonson noted that when Freud's brother Alexander asked him why he aided their escape, Sauerwald maintained that Hitler was overall justified in eradicating Jews. Freud, however, was a special case. Nevertheless, when Sauerwald was prosecuted for war crimes, Anna Freud and Marie Bonaparte asked the court to show "mercy," which it did.

The tenuous commandments

During the 1930s Freud embarked on a jarring mental journey. Anna Freud recalled that he knew cancer would kill him. As his health dwindled he dwelled on Judaism. However, as author Mark Edmundson clarified, Freud remained an adamant atheist who considered religion a neurosis rooted in "longing for a father." But just like Oedipus, he was complex. Philosophy professor Richard Bernstein pointed out that Freud professed to identify with the "essence" of Jewishness despite disavowing Judaism.

Moved by multiple motivations, Freud wrote Moses and Monotheism. Published in 1939, the book portrayed Moses as an Egyptian who liberated Jews before they murdered him in the desert. Guided by repressed guilt, the Jews supposedly devoted themselves to Moses and merged him with God in their minds. As time progressed, unconscious remorse surfaced in the form of Christianity, recreating the death of Moses through Christ.

Freud littered the book with psychoanalitic suppositions. He called circumcision a "a symbolical substitute for castration" that Moses introduced to the Jews to assert fatherly dominance. He similarly argued that incest avoidance had no rational basis, but rather stemmed from allegiance to "the father" (Moses).

Some scholars see Moses and Monotheism as a partial response to Nazism. Notably, Freud redoubled his effort to finish the book after fleeing Vienna. Moreover, in the work he argued that adherence to illusory religious figures made Jews adept abstract thinkers and thus great intellectuals. He praised Jews at a time when they were under attack.

Siggy tar dust

Be it his trademark cigar or men's trouser cigars, Freud always had oblong objects in his head. Of course, he allegedly said, "sometimes a cigar is just a cigar." Tragically, in his case a cigar was also a sickness. In 1923 he was diagnosed with a severe form of jaw cancer, which a doctor attributed to his smoking, according to The Atlantic. Over the next 16 years he endured approximately 30 surgeries, which chipped away at his face until he needed a prosthetic device to separate oral and nasal cavities.

Anna Freud waited on her father around the clock. Freud also had invaluable help from Max Schur, a doctor recommended by Marie Bonaparte in 1926. Schur scheduled his surgeries, directed his treatments, and treated him like a true friend. He stayed with Freud when Anna was arrested, then went with Freud to London, where he continued treating him. Apparently, the pair also made a grave pact.

In 1939, the year Hitler invaded Poland and Moses and Monotheism was published, Freud had reached the end of his rope. Hopelessly frail and ailing, he grabbed Schur's hand and uttered, "My dear Schur, you certainly remember our first talk. You promised me then not to forsake me when my time comes. Now it's nothing but torture and makes no sense anymore." After receiving Anna's permission, Schur administered morphine. After two injections, Freud slipped into a coma and died. One can only wonder if he dreamed.