False American Revolution Facts You Always Thought Were True

No one doubts the gloriousness of America's roots. The American Revolution saw the colonists rising up against their oppressors, the David who kicked the butt of Goliath and then became a symbol of freedom and liberty. These are the stories that make Americans proud of their history. But that sort of romanticism has allowed a lot of myths to perpetuate, too. Stories of battles, liberty bells, minutemen, and a bunch of dudes throwing tea into a harbor are so much more entertaining with a little embellishment, so a lot of what we think we know about the Revolutionary War is either an exaggeration or just a total falsehood that somehow survived long enough to end up in a history book.

So listen, my children, and you shall hear ... not the story of the midnight ride of Paul Revere because you probably already know that one is totally made up. But here are a few others that you might not have known were fabrications — not that the truth is any less glorious than the made-up American Revolution is.

Goliath vs. David (and France, Spain and Holland)

The colonists might have been a bunch of mountain men with a poor sense of fashion and no taste for Marmite, but they weren't naive. They knew that England was big, bad, and had already conquered half the world. According to ThoughtCo, the colonists knew they needed help, so they asked Britain's longtime BEF (best enemies forever) France, which was willing to overlook the whole Protestant, monarch-overthrowing thing if it meant kicking some British butt, even if it was just providing the boots for it.

At first, France didn't want England to know they were helping the colonists, so they invented a fake business and used it to funnel gunpowder, cannons, and clothing to American soldiers. In fact around 90 percent of the gunpowder America used in the two years after the Declaration of Independence came directly from the fake French business.

After it became clear that the colonists might actually win, France became a little more open in its support. The French infantry played a big role in the 1781 victory at Yorktown, and then Spain got involved, too, because Spain was still annoyed at England for beating them in the Seven Years' War. Then Holland got on board, and pretty soon the war was over. America was an independent nation, but it depended on a whole lot of other nations to get there.

Freedom for all, even if you don't really want it

It's hard to imagine that there was anyone in the colonies who wanted to be ruled by an all-powerful, self-absorbed monarch who lived on another continent, but for a lot of people, it was just easier that way. So although we love to think the War for Independence was something everyone was in favor of, the reality was that it wasn't even 50-50.

For those of us who are a little less idealistic there's the one-third myth (thought to have been perpetuated by John Adams) that the split was really three equal parts: Patriots (those who wanted independence), Loyalists (those who supported the crown), and undecided. The problem with those oft-repeated figures is they came from one of Adams' writings about the French Revolution, not the American Revolution.

The best numbers about who supported whom come from historian Robert Calhoon: 20 percent Loyalist, 45 percent Patriot, and 35 percent undecided. So not a minority, but hardly overwhelming support, either.

And just to add to that sense of disharmony, the University of Notre Dame reminds us that there was actual physical conflict between Patriots and Loyalists — in some areas there were even "regional mini-civil wars" that took the lives of Americans who should have been standing together.

The patriots were not a rag-tag band of badass farmers

Early in the war, the middle-class farmers were the backbone of the revolution. And then they were all, "Welp, gotta go home and plant some stuff," and the army found itself without most of its army.

According to U.S. News and World Report, their replacements weren't exactly the same idealistic, determined, freedom-loving souls that preceded them. They were poor, young laborers who were mostly in it because they'd been promised land and money. In other words, they were fighting for the land of the free stuff, home of the bravely fighting for more free stuff. Not that there's anything wrong with being a professional soldier as long as you do your job, but it was hardly an army of idealism.

Once things started looking bad for Washington and his depleted army, Congress decided to offer men who enlisted for "the duration" the generous sum of 20 bucks, a suit, and 100 acres. Farmland in America today is worth on average around $3,000 per acre, so that would be a nice modern bonus if you know how to use it. For comparison, a newly enlisted soldier in today's army can expect a salary of $18,000 to $23,000 a year.

The Liberty Bell was actually about to fall through a rotted building

The image of the Liberty Bell tolling to announce the signing of the Declaration of Independence is an enduring one, and also it attracts a lot of tourists to Philadelphia. But according to the Independence Hall Association, the Liberty Bell didn't ring on July 4, 1776. In fact no bells at all were rung in Philadelphia in that capacity until July 8, when the people were summoned to hear the first reading of the Declaration. But even then there's doubt that it was actually the Liberty Bell that brought people to the town square — the Liberty Bell was way, way up in a wooden steeple that was literally rotting away. For the most part, Philadelphia avoided ringing it because of the very real fear that the whole tower would come down and kill someone.

The story of the ringing of the Liberty Bell didn't even appear in popular consciousness until 1847, and that was in a short story by novelist George Lippard, who called it the "State House Bell." In fact the name "Liberty Bell" didn't stick until after 1876, a couple decades after it was coined. So not only did the bell probably not ring out to declare the newly declared liberty of all (white, male) Americans, it wasn't even associated with the word "liberty" until a full century later.

One shilling a year? Outrageous!

Everyone knows one of the biggest factors in the dispute between the colonies and Great Britain was taxes. So from there, we kind of just assume the tax rate was ridiculously high, like "taxman comes for half your crop or your eldest daughter" high. But according to PBS, the truth is that on average, the colonists had to pay roughly 1 shilling per year in taxes, which is about $3.20. That's in 21st-century money, by the way, not in 1776 money. By contrast, people who lived in Great Britain had to pay 26 shillings a year, which equals about $83.20.

So really, the idea that anyone at all would be whining about high taxes in 1776 seems ridiculous, but that's not the point because the colonists weren't actually whining about taxes — what they were whining about was the fact that they had no representative in the British parliament, despite the fact that they were paying taxes. Sort of like if you had to pay a fee to your cell phone company every month, but you weren't actually allowed to have a cell phone. There, a modern analogy that pretty much anyone can internalize, right?

Happy Third of September

So July 4, 1776, arrived, and the Declaration of Independence was signed, the Liberty Bell didn't ring, and freedom spread across the land. But actually, the only part of that sentence that's true is the part with the signing of the Declaration of Independence. The Declaration of Independence was just that — a declaration, meant to inform the British empire that Americans no longer considered themselves British subjects or bound by British law. And as you can probably guess, the British were not cool with this, so it's not like they got the Declaration in the mail and just shrugged.

According to History, the Declaration of Independence was signed 442 days after the first engagements of the Revolutionary War (the battles of Lexington and Concord), but five years before the actual end of the war. That was also seven years before the U.S. become officially free, when the Treaty of Paris was signed on September 3, 1783. So really, those firework and barbecues ought to happen a couple months later than they do. Plus, they wouldn't always fall in the worst heat wave of the year, but whatever, America.

We hold these truths to be self-evident ... most of us, anyway

By now you might be letting go of the idea that everyone in America liked the idea of independence. According to the Schiller Institute, on June 1776, the resolution for independence was presented to Congress, and four of the 13 colonies were not ready to get on board. The most anyone could get out of them was that maybe someday, if things go well and there are no unexpected roadblocks, and the wind is blowing in the right direction, then maybe we would be kind of ready to be independent. Sort of like when your mom tells you that maybe one day you can have a pony.

So Congress decided to delay the vote until the first week of July so they could put something in writing. Thomas Jefferson crafted the poetic, persuasive document that came to be known as the Declaration of Independence, and on July 2 the other colonies went all fanboy on him and by the end of the debate everyone was ready to sign, except New York because apparently New Yorkers have always liked to stir the pot. New York abstained on the grounds of not having "specific instructions" from their home state. So even when everyone gathered around to sign the document on July 4, New York still wasn't officially on board. New York joined the popular kids a few days later.

Guerilla warfare

One of the most enduring legends of the Revolutionary War is the one in which the colonists, who knew the terrain much better than the British, hid in the woods and picked off the Redcoats with rifles, winning the war guerilla-style.

According to American Heritage, it is true that American fighters did know some things the British didn't. They'd been fighting Native Americans for 150 years, so they not only understood how to fight in the wilderness, they also learned some tricks that had most definitely not been passed down over centuries of traditional European warfare. But that doesn't mean the British weren't familiar with a lot of those tricks — they'd fought the Scots, who lived in similarly wild lands, and they'd even had experience on the ground in America during the Seven Years' War.

So yes, guerilla tactics played a role in the American Revolution, but they didn't win the war. In fact the colonists deliberately exercised some restraint in employing non-traditional warfare, mostly because they didn't like what it said about them as a people — they saw themselves as living in a golden age of civility and wealth, and guerilla warfare didn't jive with that worldview. So they won the war the old fashioned way — out in the field, in formation, just like you do when you're bored and have nothing to do but play warfare games on your iPad.

Minutemen helped win the war

Right up there with Paul Revere's midnight ride (which didn't happen) and Molly Pitcher (who probably didn't exist) is the myth of the minuteman, who was a noble military volunteer: highly trained and terrifyingly accurate with a rifle. Of course by now you know where this is going — the truth is that although minutemen did have more training than your run-of-the-mill militiaman, according to the Revolutionary War Journal, they had no central leadership, very little discipline, and for the most part couldn't hit the backside of a bovine with a hillbilly guitar.

It wasn't entirely their fault — there were very few rifles in the American military at that time, so the minutemen were mostly using muskets, which could turn just about anyone into a crap shot. Flintlocks were available, but achieving accuracy with a flintlock required a lot of practice. And the minutemen couldn't really do that because the gunpowder was mostly being reserved for actual fighting.

Minutemen were said to have played an important role in the battles of Lexington and Concord, but the numbers really aren't that impressive: 73 British killed and 174 injured — compared to 3,763 Americans joining the fight. So that kind of does say something about how good they were at actually hitting a target. Still, we love the idea of a loyal citizen taking up arms for a noble cause, and that's probably why the minutemen have endured as symbols of the American Patriots.

The Boston Massacre was a bar brawl

Something like 250,000 people were killed during the Nanking Massacre of 1937, and 34,000 were murdered by the Nazis during the Babi Yar massacre in 1941. So the first time you heard the words "Boston Massacre," you probably thought it was a bloodbath — hundreds, if not thousands of casualties, which is what you'd typically expect from an event that was labeled a "massacre."

Actually, the Boston Massacre was a bar brawl. Now, that's not to say that the five lives lost there weren't important, but a massacre ... eh ... not really. Here's what History says happened: A bunch of guys at the Customs House in Boston started throwing snowballs at a British soldier. But instead of throwing snowballs back, which is what normal people do in a snowball fight, he called for help and seven more soldiers showed up. Then one of them tripped, and his rifle accidentally discharged, and when it was over five people were dead and three were wounded.

Let's not underestimate the power of words, though. It would have been pretty tough to get the public worked into a war frenzy over the "Boston Bar Brawl," so "Boston Massacre" it was, and today we remember those five deaths as the first casualties of the American Revolution.

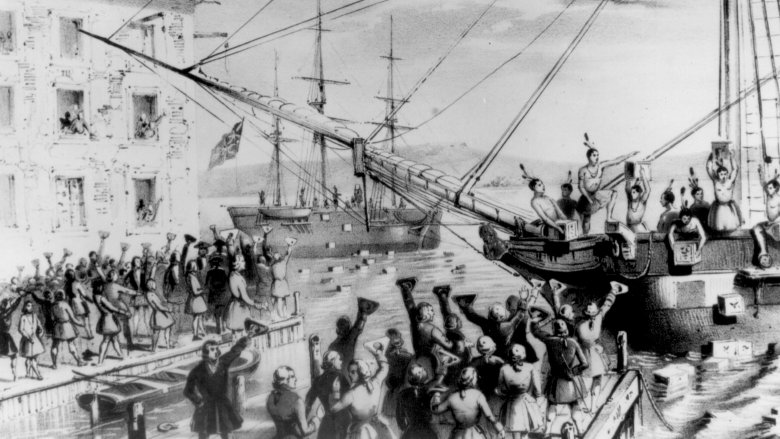

Taxes again

The event inspired a whole political party, albeit a couple centuries later, but was it really the great act of defiance against an oppressive government that history likes to say it was?

According to History Net, on December 16, 1773, a bunch of guys disguised as Mowhak Indians boarded a ship belonging to the East India Company (the people who were after Captain Jack Sparrow) and dumped the contents of 340 crates of tea into Boston Harbor.

Remember that in those days Amercians were still very British, so when they found out, they mostly just gasped and thought, "What a horrible waste of tea!" Most of them were also worried that the act painted the colonists as lawless vandals, which really wasn't good for the noble cause of the revolution. So no one really celebrated the event until long after it was over.

But here's the worst part: The Boston tea party was not an opposition to high taxes on tea, which is what most people think. In fact, taxes on British tea had just been cut, which meant it was now a lot cheaper than it used to be. So what were those Mowhak-clad colonists mad about? Well, the cheap tea was wrecking John Hancock's smuggling business. Yes, the guy best known for his huge signature was also smuggling duty-free tea from Holland, so that cheap British tea had to go. Freedom!