The Nazis' War Against 'Degenerate Art'

Though typically emerging as a conservative movement, fascism tends to have little interest in conserving very much at all. Instead, such movements as those that took power in several European countries in the early twentieth century tend to be on a mission of destruction and resurrection.

Fascism is inherently warlike, as proven by Adolf Hitler's National Socialist (Nazi) regime in the late 1930s, which sought to expand into other European countries to establish German domination over the continent.

But the Nazis and their ilk didn't only go to war with other countries: They went to war with their own, targeting established institutions, racial ethnicities, and even culture itself. Beginning in May 1933, the Nazis held regular book burnings, destroying works by Jewish writers, those aligned with communism, and any other books which they deemed incompatible with their dream of establishing a purely "Aryan" race of Germans, whose society would be governed along totalitarian lines. But their propaganda campaign went further, with an all-out war against modern art, which they described as "decadent" and characterized as depraved and a reflection of sick minds working in a sick society. Here is the true story of how the Nazis tried to destroy art itself.

The modern art explosion of the early 20th century

In the decades before the Nazis came to power, European art had been enjoying a significant period of evolution and innovation. Indeed, the art that Adolf Hitler and his supporters sought to take steps against was, in general, a part of a single major movement: modernism.

Modernism, a movement that occurred in all forms of art from painting to literature, has proven a difficult concept to define, but it is generally considered a period during which artists knowingly attempted to break with the past amid the conditions of modernity. In visual art, these breaks took the form of various waves of experimentalism known as "Secessions" — breaks from the past — which took place throughout Europe around the turn of the 20th century. The Vienna Secession, for example, was spearheaded by the work of art nouveau practitioners such as the now-iconic Gustav Klimt, whose lustrous, gold-embossed works sought to reflect organic forms and were unapologetically sexual. Other secessions occurred in cities such as Munich and Berlin, encompassing a multitude of new styles and subject matter, which pushed the boundaries of art as it had been practiced in the 19th century.

This generation of art, and the next, was what Adolf Hitler and the Nazi party would later consider dangerous. But opposition toward modern art wasn't anything new in Germany.

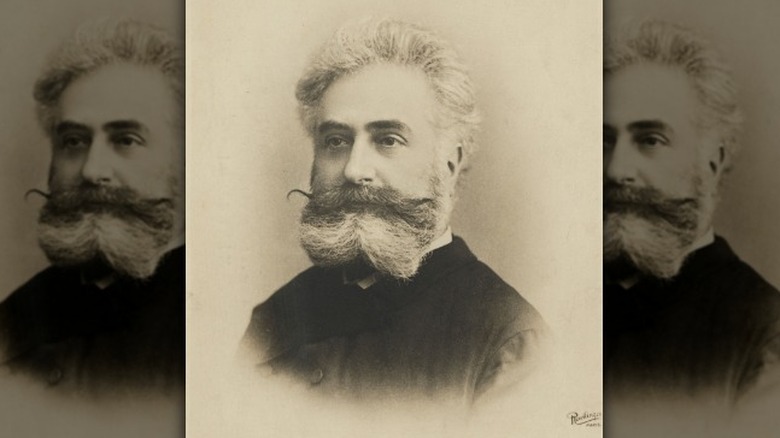

Max Nordau and the theory of degeneration

It is not often that the ideas of an academic trickle into the wider public consciousness and come to frame the anxieties of an era. But that is precisely what happened in the late 1800s, when a controversial work by the Hungarian thinker Max Nordau was published and became highly influential.

The book, "Degeneration," first published in Germany in 1892, presented a reading of the era's culture as ultimately neurotic and unhealthy. Nordau argued that the philosophy and literature that had taken hold during the period threatened European morality, which had first been established during the Renaissance, and that the art emerging at the time was a symptom of societal decline, or degeneration. Nordau's views were controversial, but reflected a growing suspicion around all forms of modern art that was fomenting long before the Nazis rose to power. Indeed, new modes of painting, such as impressionism, had been widely derided by critics and the public all the way back to the middle of the 1800s.

Adolf Hitler: failed artist

The factors leading to the rise of Nazism and the party's crackdown on modern art are manifold. Nevertheless, art historians have often pointed to one specific life story in the fascists' turn against "decadent" artists: that of Adolf Hitler himself.

As a teenager, Hitler dreamed of becoming an artist. In 1907, at the age of 18, the future Führer moved to Vienna, where he attempted to enroll at the Academy of Fine Arts. He took the entrance examinations but was rejected by the admissions panel. Hitler's artistic dreams were fading, and he was forced in the years that followed to live a hand-to-mouth existence in the city he'd found himself in, selling simple scenes he'd painted for small sums of money. It was perhaps this training, coupled with his own resentment toward the art establishment that had rejected him, that made Hitler develop a fundamentalist attitude toward what good art is. Namely, that which accurately represents the world around us, and which is consumable by everyday people — the exact opposite of what was happening in the world of modern art, which was consuming the academies at the time.

Hitler later relocated to Munich, where he continued to paint for a living, before signing up to join the Bavarian Army following the outbreak of World War I. He received both commendations and injuries during his time as an infantry courier and was enraged by Germany's ultimate defeat, which he blamed on "degenerate criminals." He decided to forget about art ... and instead turned to politics.

World War I created a generation of pacifist artists

Germany's defeat in 1918 instilled in many young men — such as Adolf Hitler — an extremist hatred that would ultimately lead to the creation of a fascist state. Nonetheless, others persevered with art in an attempt to express the horrors they had endured during four years of atrocious violence and chaos.

One of the most prominent German artists that went on to capture their experiences of the Great War was Otto Dix, a machine gunner during the bloody Battle of the Somme, who later suffered from nightmares about what he'd seen. Dix's 1924 collection "Der Krieg" ("The War") captured in grisly detail the gruesome realities of trench warfare, including rotting corpses and human skulls stripped of their flesh. Other artists, such as Max Beckmann and Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, suffered severe mental breakdowns.

Such artists returned from World War I avowed pacifists, which was strongly expressed in the works they went on to create. Years later, these anti-war sentiments would be a significant thematic motif in modern art — which would see them condemned by the jingoistic Nazi Party.

The Nazis' idea of purity in art

An overwhelming pacifist sentiment detectable in much modern art of the early twentieth century drew the ire of the rising Nazi Party. But several other complex factors led to some of the period's greatest artists being denounced as "degenerate" and immoral.

The Nazis drew a parallel between aesthetic purity and national pride. Adolf Hitler himself, whose views on art are found in his book, "Mein Kampf" ("My Struggle") and numerous speeches given to his followers, railed against modern art. He denounced it as a dissolute aesthetic practice concocted by enemies of the state — the intelligentsia, whom the Nazis portrayed as culturally Jewish in nature — and echoed Max Nordau in his belief that such works would lead to irreparable moral and societal decline.

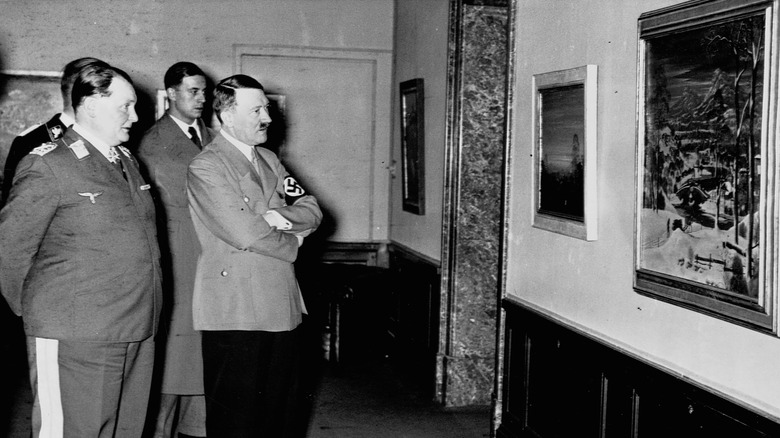

What the Nazis proposed instead was a vision of art as a reflection of racial and societal purity, glorifying the "Aryan" race, whom Hitler claimed was the driving force behind the cultural glories of ancient peoples like the Greeks and Romans. He believed the genetic lineage of these civilizations was carried by "pure" bred Germans, who must glorify their own nation again through a nationalist art through which a new Germany could be idealized, as opposed to a cosmopolitan, disjointed vision of the world as offered by the modernists. What resulted was the "Great German Art Exhibition" in Munich, an annual event that from 1937 presented to visitors the idealized, antiquity-inspired art of which the Nazis approved.

The Nazis vs. Bauhaus

As well as being a frustrated painter, Adolf Hitler often expressed to those around him that he was also something of a frustrated architect, having developed a taste for opulent, imposing buildings during his years as a street artist in Vienna and Munich. He later took great pleasure in expressing his imperial aspirations for Nazi Germany through the construction of classically-inspired buildings.

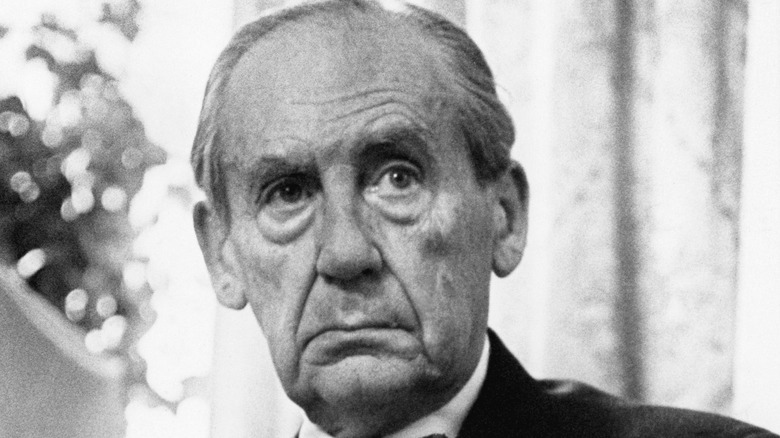

Hitler also instigated a concurrent attack against the breeding ground of a new form of architecture and art: the Bauhaus. This school was founded by the influential German architect Walter Gropius (pictured), who in his manifesto of 1919 implored a new generation of creatives: "Let us strive for, conceive and create the new building of the future that will unite every discipline, architecture and sculpture and painting, and which will one day rise heavenwards from the million hands of craftsmen as a clear symbol of a new belief to come." The Bauhaus comprised several of the most celebrated artists of the period, including Wassily Kandinsky and Paul Klee.

But the Nazis took aim at the idealistic vision at the core of the Bauhaus movement, describing it as Bolshevik and socialist, and in 1933 the Bauhaus headquarters in Dessau was permanently shut. Though its individual practitioners attempted to resurrect the Bauhaus in other locations and to minimize actions that may be interpreted as overtly political, the movement eventually relocated overseas.

The crackdown on modern art

The Nazis' assault on "decadent art" escalated throughout the 1930s, as they shut museums and galleries, fired curators and professors from their posts, and seized artworks they deemed offensive. By 1937, it is estimated that they had confiscated around 16,000 artworks from across Germany, transforming the lives of the people involved.

Artists from across Europe whose works were displayed in German galleries had their presence in the art world wiped out overnight. Among them were some of the most famous artists of all time, including Pablo Picasso, Vincent Van Gogh, and Paul Cézanne. But it was living German artists who faced the most ruin.

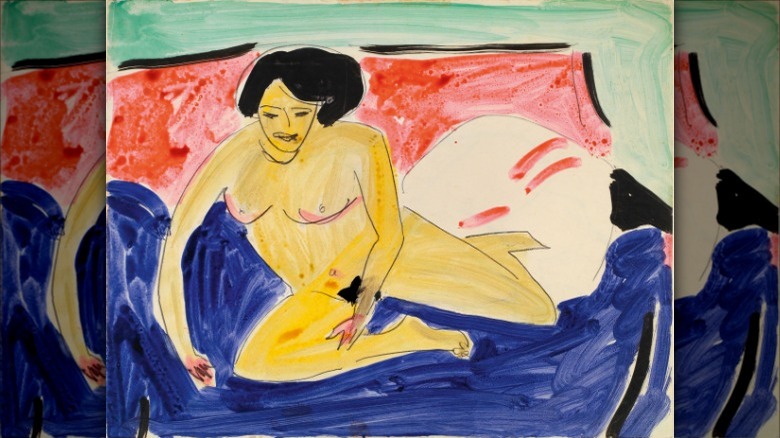

For example, the painter Ernst Ludwig Kirchner (one piece is pictured above, "Seated Nude on Divan," from 1909), who at the time was living in Switzerland, had some 639 works confiscated from German galleries — and the Nazis went a step further, by having him expelled from the Academy of Arts in Berlin. Another painter, George Grosz, had around 300 of his works destroyed outright.

The Nazis' degenerate art exhibition

In July 1937, a new Nazi-curated exhibition opened in Munich, titled "Entartete Kunst," or "Degenerate Art." Intended as a counterpoint to the "Great German Art Exhibition," which demonstrated the artworks of which the Nazis approved, "Entartete Kunst" was filled with scores of works from artists whose works had been seized and whose careers had been shattered. Emil Nolde was chief among the 112 artists displayed, with 27 of his works adorning the walls of the exhibition.

Of course, "Entartete Kunst" was not a celebration of such artists, nor was it an impartial display for the benefit of a curious modern art-loving public. It was an act of propaganda, in which the German public was invited to view a total of 650 creations of what the Nazis deemed were sick and twisted minds. Paintings were hung haphazardly, crammed together on the gallery walls, and adorned with slogans attacking the works for what the Nazis perceived as their Jewishness, Bolshevism, and immorality. It was an exercise in public mockery, intended to turn the German public against modern art once and for all.

Presaging the opening of "Entartete Kunst" with a speech at the "Great German Art Exhibition," Adolf Hitler declared: "From this moment we shall conduct a merciless war against the remnants of our cultural disintegration."

German artists on the run

As the Nazis' crackdown on modern art reached a fever pitch, individual artists increasingly found themselves being banned from exhibiting and selling their works. They lived with the threat of having their art confiscated or, at worst, destroyed. Unsurprisingly, many of those that could afford to chose to flee, with neutral Switzerland emerging as a common destination for artists and art collectors.

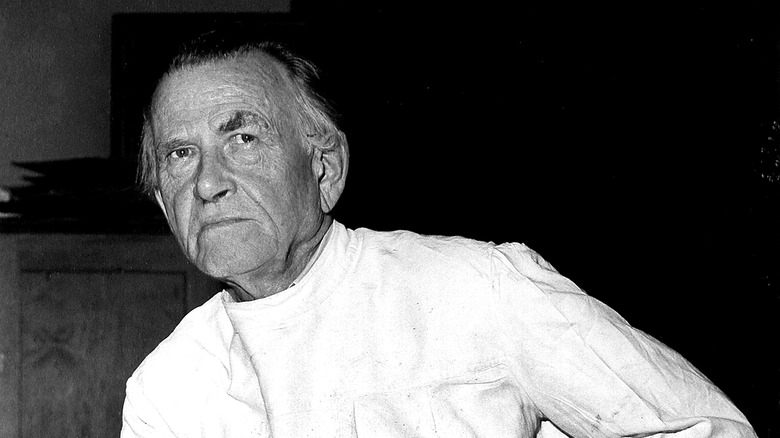

The acclaimed German painter Max Beckmann (one work pictured above, "Self Portrait," from 1943) had been following Hitler's rhetoric during the ongoing war against modern art. With ever-increasing hostility toward artists of his kind, he and his wife fled Berlin for Amsterdam, where he lived and painted in exile.

But even those who had escaped Germany to make their art elsewhere felt the ever-growing threat of Nazi expansionism. One tragic tale is that of Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, who, though he had left Germany for Switzerland, was deeply affected by the Nazi's annexation of Austria in March 1938. Increasingly anxious that the Nazi soldiers would soon be at his door, the celebrated artist died by suicide at the age of 58.

If you or anyone you know is having suicidal thoughts, please call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline by dialing 988 or by calling 1-800-273-TALK (8255).

The 1939 degenerate art auction

Despite their efforts to ensure that so-called degenerate artists and their work were publicly reviled, the Nazis understood that the works in question held a great deal of value to international collectors. Looking to raise funds for the party in 1939, Nazi officials selected 125 works from international artists, including Vincent Van Gogh and Pablo Picasso, as well as German modernists, to be sold on the international art market via the Galerie Fischer, located in Lucerne, Switzerland. Of the thousands of confiscated works that remained in the Nazis' possession — after the most valuable pieces had been sold off — most are believed to have been burned en masse in Berlin later that year.

An exhibition at New York's Neue Galerie in 2014 attempted to recreate the Nazi's "Degenerate Art" exhibition, but with a different angle. In place of those artworks that had been lost or destroyed, there hung empty frames, painfully highlighting the cultural vandalism of the Nazis' war on modern art.

The post-war recovery in European Art

The damage that the Nazis caused to Germany's cultural heritage through its war on modern art is incalculable. To this day, experts are still piecing together the fates of many of the surviving works of art, and determining what masterpieces may have been destroyed. But in the years after the defeat of the Third Reich in 1945, modern art once again began to thrive in Germany. It took over a decade, but Germany began to emerge as a hotbed of artistic activity in Europe, with German artists' re-engagement with expressionism and innovations in photography propelling the country's art scene well into the 1990s.

Elsewhere, artists whose lives had been thrown into disarray by the Nazis were eventually reassessed, and their genius celebrated. The work of Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, for example, whose estate took years to settle after his tragic suicide, was, after decades in storage, finally shown to the public at the Kirchner Museum in Davos, Switzerland, which opened in 1982.

And the imperial, "Aryan" art of which the Nazis approved? Either destroyed in the final years of the war, or languishing in a U.S. Army warehouse, which also holds Adolf Hitler's own watercolors.