Why These Famous Historical Figures Were Acquitted Of Murder

Thankfully, most people will make it through their whole life without getting accused of murder. But some people will end up in court charged with killing someone, and occasionally, those defendants are either well-known then or will become well-known after. And not just because of the trial; there are plenty of people who went on to do great things with their lives after they were accused of murder.

In all these particular cases, however, the defendants were found not guilty in the end. Whether it was because they were believed to have acted in self-defense, or had very good lawyers, or made sure the whole justice system was rigged in their favor, juries weighed the evidence and decided they weren't murderers.

So were they all actually innocent, or did they just get very lucky? From politicians to activists to celebrities, here's why these famous historical figures were acquitted of murder.

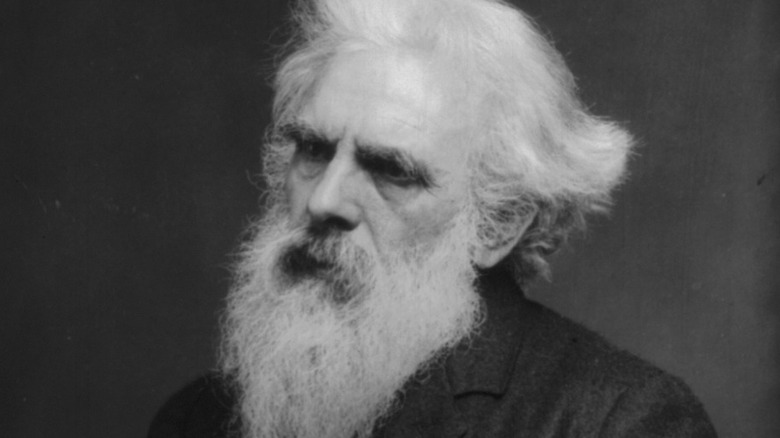

Eadweard Muybridge

You'd have to live quite the life for someone to eventually produce a biography called "The Man Who Stopped Time: The Illuminating Story of Eadweard Muybridge – Pioneer Photographer, Father of the Motion Picture, Murderer." But the lengthy title of Brian Clegg's account of Muybridge doesn't even scratch the surface.

Born Edward Muggeridge in 1830 before changing his name to the much cooler Eadweard Muybridge, he traveled the world and helped advance the art of photography from its earliest days. Eventually, he became a pioneer in the sort of stop-motion imagery that would lead directly to the ability to make films. If you've ever twirled a sort of lampshade-looking thing with horses printed on the inside, which makes it look like the horse is running, that's Muybridge.

But in the middle of this amazing career, Muybridge shot and killed a man. Harry Larkyns was having an affair with Muybridge's much younger wife, and in fact, it was likely that Muybridge's child was actually fathered by Larkyns. So Muybridge tracked Larkyns down at the house where he was staying, asked to see him, and shot the man straight in the heart. He then apologized for the inconvenience to the women of the house and waited to be arrested. While the crime could have resulted in a death sentence, the jury ended up finding Muybridge not guilty, with the logic that even if technically illegal, it was not morally wrong to kill a man who had slept with your wife.

Lizzie Borden

Lizzie Borden was not famous before she was accused of a particularly violent double murder, but the crime and her infamous acquittal have made her a household name for generations. Lizzie was an unmarried 32-year-old living with her wealthy father and despised stepmother in 1892. The household also comprised a maid named Bridget Sullivan and Lizzie's older sister Emma. However, Emma was away when the crimes occurred.

According to "The Trial of Lizzie Borden" by Cara Robertson, the first sign anything was wrong was when a neighbor noticed Lizzie just standing in the doorway of her house. When asked if everything was okay, Lizzie replied, "Oh, Mrs. Churchill, do come over. Someone has killed father." That was an understatement. Both Andrew and Abby Borden had been hit multiple times with what was most likely an ax or hatchet, doing extreme damage to their bodies. From the beginning, it seemed like the culprit had to be an insider. There were no other signs of a disturbance than the two dead bodies. No one had heard anything. And — strangest of all — it was eventually determined that at least 90 minutes had elapsed between Abby's murder and Andrew's. Not many ax murderers hang around.

Eventually, Lizzie was arrested for the murders, but people found it almost impossible to reconcile the horrific crime with the woman in court. And there were difficult questions, including how she could have avoided getting blood all over her clothes. It took the jury a little more than an hour to return a not-guilty verdict.

Harry K. Thaw

Harry K. Thaw came from new money and married the notoriously beautiful model and actress Evelyn Nesbit in 1905. However, Nesbit, who was in her very early 20s (although her correct birth year is unknown), had been in a serious relationship before that. When she was around 16, she began a relationship with the famous architect Stanford White, who was three decades older.

When Thaw became obsessed with Nesbit, he knew about her relationship with White but saw himself as saving her from a dirty old man. Nesbit could tell there was something off about Thaw, who was known to have a violent streak. She kept him at arm's length, but he kept pushing, even taking her to Europe and trying to get her mother to force the young Nesbit into a relationship with him. It didn't help that he was obsessed with women being virgins until they married, which Nesbit was decidedly not. Eventually, she told him that White got her drunk and raped her, although it's unclear if this is what really happened or if she was trying to placate Thaw.

Thaw and Nesbit finally married, and the next year Thaw shot Stanford White to death at a theater performance in front of hundreds of witnesses. At Thaw's sensational trial, his defense was that he'd killed White in a moment of temporary insanity because of what the architect had done to Nesbit. His first trial resulted in a hung jury; he was acquitted at his second one.

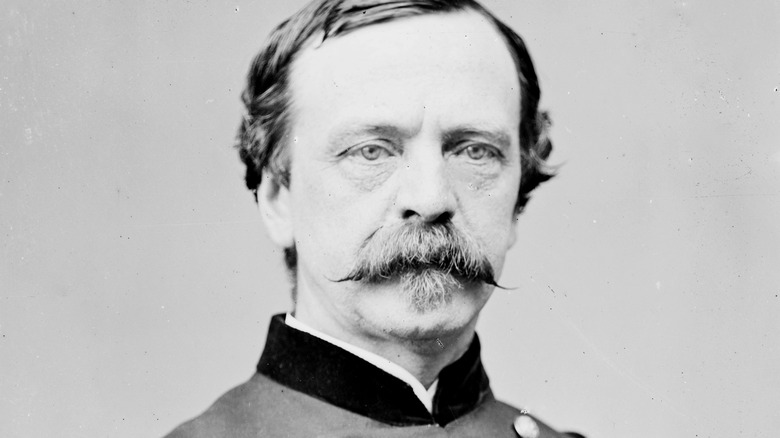

Daniel E. Sickles

Daniel Sickles was a sitting congressman from New York in 1859 when he shot and killed Philip Barton Key, himself a U.S. district attorney as well as the son of Francis Scott Key. Daniel had recently learned that Key was having an affair with his wife Teresa, thanks to an anonymous letter that would eventually be reprinted in national papers including the White Cloud Kansas Chief. It revealed to Daniel how Key "rents a house ... for no other purpose than to meet your wife ... he hangs a string out of the window, as a signal to her that he is in, and leaves the door unfastened, and she walks in ... With these few hints, I leave the rest for you to imagine."

Daniel, while no faithful spouse himself, was seemingly the last person in Washington, D.C., to know about his wife's affair with Key. Teresa confessed to him when confronted, and before she could let Key know that her husband knew about them, her lover turned up outside their home and signaled for her. Daniel, having seen the signals, emerged from the house a short time later and shot him dead.

At his trial, Daniel's defense team allowed that he admitted shooting Key and intending to kill him. He claimed temporary insanity and was found not guilty, with the jury's verdict leading to cheers in the courtroom. However, Daniel would cause far more scandal when he got back together with Teresa after his acquittal, which Washington society could not accept.

Sojourner Truth

Technically, Sojourner Truth was never mixed up in a murder. That would be Isabella Van Wagenen, who had actually been born into enslavement around 1797 as Isabella Baumfree. She escaped to freedom in 1826, eventually ending up in New York City. It was there that the future Sojourner Truth found God, which would end up getting her in a lot of trouble.

Through her work as a servant and housekeeper, Truth was introduced to a Pentecostal version of the Methodist church. And it was because of this group of worshipers that she met "Prophet Matthias." He would eventually lead Truth and other followers to a communal living arrangement that was effectively a cult, with all the abuse, control, and strange sex stuff that goes along with your average cult. A man named Elijah Pierson bankrolled the group until one day he got violently sick. Matthias refused to let anyone call a doctor, and Pierson died.

Another member, Benjamin Folger, accused Truth of not only conspiring with Matthias to kill Pierson but of trying to poison him and his wife as well, because they had once gagged after drinking coffee she made them. After Folger's accusations, Pierson's body was exhumed and an autopsy determined that he had been poisoned. Truth took the huge gamble of taking Folger to court for libel over his accusations, but she won, and managed to avoid going on trial for the murder. Matthias would also eventually be acquitted of the murder charge in criminal court.

Bill Lancaster

Charles Lindbergh and Amelia Earhart were not the only famous pilots of the 1920s and '30s. Englishman Bill Lancaster met Australian Jessie "Chubbie" Miller in 1927. They were both married to other people, and at first, their relationship was purely about flying. Lancaster agreed to bring Miller on a flight from England to Australia, which ended up giving her the record for the longest flight by a woman, even though she didn't actually do any of the flying over the five months it took to make the journey.

By the end of their adventure, the pair were romantically involved. However, they spent the next several years in an on-off relationship, and Lancaster even tried to repair his marriage at one point. Miller got her pilot license and ended up setting more records. In 1932, she decided to write a book about her life — or rather, to hire someone to write it for her. That was how Haden Clarke moved in with Miller and Lancaster and ended up in a deadly love triangle. Clarke went so far as to ask Miller to marry him while Lancaster was away. Distraught, Lancaster returned home. On April 20, 1932, Clarke died from a gunshot to the head.

While Lancaster was charged with murder, he insisted that Clarke had died by suicide. At trial, Lancaster came off as an outstanding person and Clarke's past was cast in an unfavorable light. The jury believed it had been suicide and returned a not-guilty verdict.

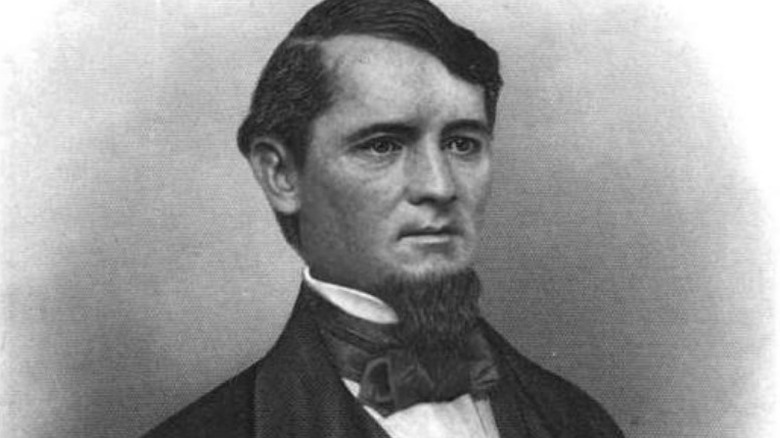

William Hawkins Polk

While James Polk made it all the way to the presidency of the United States in his political career, his younger brother William Polk was also a successful politician. He served in the Tennessee legislature, then was appointed ambassador to Naples, and was finally elected to the U.S. House of Representatives. What makes this even more impressive was that it all happened after he killed a man.

In 1838, the 23-year-old William traded insults with Richard Hays. What started as some snide remarks about a ball they were going to attend escalated to "Real Housewives" levels when William threw wine in Hays' face, so Hays threw his own drink at William. Seemingly out of wine to throw, the two men started punching each other. Apparently, it wasn't a fair fight, with William thoroughly kicking Hays' butt. It had seemed like the pair were willing to let bygones be bygones, except that Hays told everyone who would listen he beat up William. To defend his honor, William tracked Hays down again, and this time he horse-whipped him. Their escalating conflict was about to become deadly. Hays took up target practice while openly admitting he was planning to kill William. However, when Hays confronted him, his shot missed. William's didn't.

With Hays dead, William Polk was arrested for murder. However, a grand jury decided he'd acted in self-defense and was only guilty of assault. Along with paying a fine, William would spend just six weeks in jail.

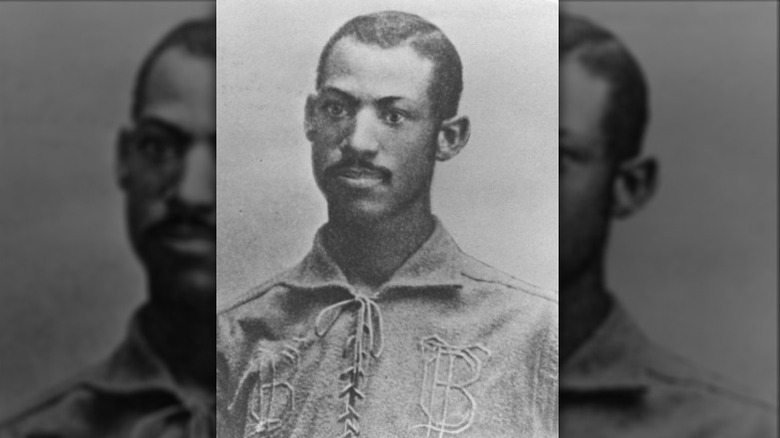

Moses Fleetwood Walker

Jackie Robinson is often credited with being the first Black man to play Major League Baseball, but the truth is that he was the first Black man to play after the league introduced segregation. But in the 1800s, a few Black men played in the majority-white league. One of the very first was Moses Walker.

Born in 1856, Walker would later attend college, where he played baseball — and played it extremely well. Offered a job in a semi-pro league, Walker discovered in his very first game that some white players flat-out refused to participate if there was a Black man on the field. While he went pro within a few years and got good press for a time, racist fans became increasingly aggressive, eventually threatening to kill Walker. He left the majors for another five years in the minors.

But the violent racists were still out there. In 1891, while living in Syracuse, New York, Walker ran an errand and then went to a bar. After having a few drinks, he was confronted by an angry group of white men outside, who hit him in the head with a rock. Walker drew a knife, and one of the men ended up dead. The ex-athlete was immediately arrested and must have known that regardless of the extenuating circumstances, a Black man who killed a white man in that time and place was going to get the death penalty, if he wasn't lynched first. Astonishingly, after he took the stand in his own defense and handled it brilliantly, the all-white jury acquitted Walker.

Henriette Caillaux

There were two theories as to why Joseph Caillaux, the former prime minister of France, and Gaston Calmette, editor of the famous Le Figaro newspaper, hated each other. One possibility was that it was down to their very different politics, with Joseph leaning left and Calmette to the right. However, other people believed the men were fighting over a woman. That woman was not Joseph's second wife, Henriette Caillaux.

Whatever the reason, in 1913 and 1914, Le Figaro was publishing endless insulting articles about Joseph. Finally, the paper and Calmette went so far as to publish a letter they got their hands on that Joseph had written to his first wife when she was still his mistress. It managed to be both scandalous and painfully embarrassing as a document. Henriette believed her own correspondence might also be published at any time, and decided to take matters into her own hands. She went to the newspaper office and asked to see Calmette, at which point she pulled out a gun and shot him repeatedly.

On the stand during her trial, Henriette insisted (via Lapham's Quarterly), "When I fired the first shot, I had only one thought at the moment — to aim low, at the floor, to cause a scandal." When confronted with the fact there had been five further shots after the first one, she explained, "They went off by themselves." As the jury had apparently been rigged in her favor and consisted almost entirely of her husband's supporters, it took them less than an hour to find Henriette not guilty.

Bill Haywood

Bill Haywood was a founder of Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) or "Wobblies," but his union and labor activities included other groups as well, like the Western Federation of Miners (WFM), of which Haywood was secretary-treasurer in 1907, when he was tried for murder.

On December 30, 1905, Frank Steunenberg was assassinated. The former governor of Idaho had crushed a strike by the miners in 1899, by calling in troops, enacting martial law, and imprisoning many of the strike leaders. So when he stepped out of his house and triggered the bomb that killed him, the WFM were logical suspects.

Fortunately for Haywood — one of four men charged with the crime and the first one to go to trial — he had the famous Clarence Darrow as his defense counsel. Darrow's closing argument exhibited his talents at their absolute peak. He told the jury (via Wayland's Monthly), "Don't think for a moment that if you kill Haywood you will kill the labor movement of the world or the hopes and aspirations of the poor. Haywood can die, if die he must, but there are others who will live if he dies, and they will come to take his place and carry the banner which he lets fall." Despite Darrow's brilliance, everyone thought Haywood was done for. However, the majority of the jury members felt that the judge's instructions made a conviction virtually impossible. It took the jury 21 hours, but finally, the few holdouts gave in and Haywood was found not guilty.