What Visiting The Iconic Rainbow Room In The 1930s Was Really Like

There never was supposed to be a Rainbow Room — not if John D. Rockefeller Jr. had his way. In 1928, Rockefeller, one of America's wealthiest men, signed a long-term lease with Columbia University, worth millions of dollars, for the land between 5th and 6th avenues and 48th and 51st streets in Midtown Manhattan — the area now known as Rockefeller Center. His plan was to build a grand, modern new home for the Metropolitan Opera with shopping, dining, and offices surrounding it. But a number of sticking points slowed the process, and the stock market crash of 1929, in which Rockefeller lost half his fortune, put an end to the opera house project.

Rockefeller abandoned his philanthropic plans for commercial ones, but with the country at the very beginning of the Great Depression, he would have to turn to companies with deep pockets while catering to New York's social class as his clientele. RCA (for which 30 Rockefeller Center was initially named), NBC, and Westinghouse, among others, took up office space. On the 65th floor, near the top of the skyscraper, was a double-height amusement space for the city's wealthiest people. Initially called the Stratosphere Room for its lofty position in the New York skyline, the owners renamed it the Rainbow Room in 1934. The Rainbow Room provided anything but a dull evening for those who could afford it, and it set the standard for nightlife in New York for decades to come.

The Rainbow Room's opening party was a spectacle of New York elite

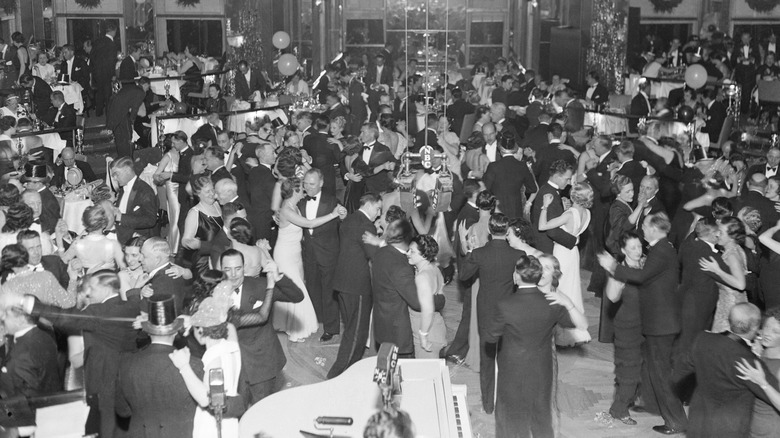

If you were invited to opening night at the Rainbow Room, you knew you were somebody. On the evening of October 3, 1934, the Rainbow Room opened its doors to an exclusive group — a true who's who of New York City elite. The opening was a "white tie" event that included everyone from the Astors to the Whitneys and doubled as a fundraiser for the Lenox Hill Neighborhood Association, The New York Times society column reported the next day. Partygoers dined, drank, and danced for hours, treated to entertainment by Radio City Music Hall organist Richard Leibert, singing by Metropolitan Opera bass-baritone Arthur Anderson, and spoken-word performances with piano accompaniment by French diseuse Lucienne Boyer.

By all accounts, people were overwhelmingly impressed by everything the Rainbow Room had to offer, with one notable exception. John D. Rockefeller Jr., who did not drink and had previously supported Prohibition, was at least uncomfortable that evening, if not altogether embarrassed by what transpired, according to Daniel Okrent, author of the Pulitzer Prize finalist book on Rockefeller, "Great Fortune." Rockefeller neither congratulated nor admonished the Rainbow Room's creators for what he likely saw as an unnecessarily indulgent endeavor, but he rarely returned to the venue. Still, the column inches devoted to the Rainbow Room's opening party in the most important papers drew enough attention so that he could focus on other matters without worrying about how seats would get filled.

Just getting to the Rainbow Room was an adventure

Although the RCA building was not the tallest in Manhattan, transporting hundreds of guests each night to the 65th floor and back to the lobby without a long wait was a very real concern to John D. Rockefeller Jr. and the Rainbow Room's management. A seemingly aimless mass of people waiting at the banks of elevators on either end would not be a good look for a luxury establishment. It was enough of a worry for Rockefeller to invest in eight express Westinghouse elevators in an already costly elevator system. According to Daniel Okrent's "Great Fortune," that expenditure added up to the second largest item in the Rockefeller Center budget at 13%, only behind the steel used to construct the entire building.

For Rainbow Room visitors, the high-speed elevators provided a sense of exclusivity, as they were in a separate part of the lobby and partitioned off from the standard bank of elevators with a curtain. Once inside, riders were shot up to the 65th floor as fast as 1,400 feet a minute, landing them at the reception area of the Rainbow Room in about 37 seconds, The New York Times reported at the time. Manhattan Borough President Samuel Levy told The Times the ride was so smooth that he could barely distinguish it from standard elevators. Because elevator speeds were previously capped at 700 feet per minute, Rainbow Room visitors were treated to the "fastest passenger elevator ride on record."

Visitors were dazzled by the lights that gave the Rainbow Room its name

When people visited the Rainbow Room, they expected to see what put the "rainbow" in Rainbow Room — a spontaneous, colorful light show that was directed by music. At the time, it was considered a technological marvel. According to a report from the New York City Land Preservation Commission, the RCA color organ detected the tone and mood of the music and then converted that information into changing colored lights projected into the area surrounding the dance floor to create an immersive experience for Rainbow Room guests. As the Brooklyn Eagle put it at the time, "If you whistle shrilly into the mike, for instance, bright yellow lights flood the ceiling. And for soft musical tones, the softer shades of light suffuse the room, (romance via robot, huh?)."

Previously, the only way to experience the color organ was at a show downstairs in the 6,200-seat Radio City Music Hall, and sometimes briefly at the occasional exhibition. That's not a surprise given how costly it was to operate. When the color organ was first installed at Radio City, the power company said it was the single largest contract from a private customer at 32 million kilowatt hours, which, at the time, was enough to power the city of 50,000 people, according to The New York Times in 1931. Putting a second one in the building in the Rainbow Room made the experience that much more exclusive.

An introduction to Art Deco and Streamlined Modernism

For the century before 30 Rockefeller Center was designed, Gothic Revival architecture and design dominated New York City. But John D. Rockefeller Jr. and his team were trying to usher in a new, modern feel for the city, starting with the RCA building and the Rainbow Room. The architects put aside the pointed arches, spires, ribbed vaults, and ornamentation associated with Gothic architecture and embraced the streamlined look of Art Deco and Modernism, with its focus on simplicity, symmetry, and geometry. The point, according to a report from the New York City Land Preservation Commission, was to have nothing compete for the attention of the Rainbow Room's visitors when it came to the venue's most impressive feature: its wrap-around, floor-to-ceiling views of New York City from the 65th floor.

To soften the sharp lines of the walls and windows, the designers introduced circles and curves, wherever possible, for a dramatic — yet soothing — effect for the Rainbow Room's clientele. Ahead of the opening, Rockefeller said the color palette would be understated. "Walls and floors will be used merely for background effects. People will furnish the brilliant colors. The long, narrow wall panels between the full-length mirrors are finished in rich brown satin," read a statement in The New York Times. "Emerald green carpets with a Greek key pattern will blend with jade green leather of the upholstered chairs. Mirrors, crystals, soft indirect lighting everywhere will give radiance."

The revolving dance floor was immediately iconic

As if the color organ wasn't enough, the Rainbow Room's owners found other ways to make waltzing and foxtrotting across the dance floor something truly unique for their guests. The Rainbow Room had a famous revolving dance floor that was 32 feet in diameter. According to a report from the New York City Land Preservation Commission, it could spin in either direction and had two different speeds, which would come full circle every three to five minutes. The rotating dance floor incorporated another layer of movement to the experience, but, more importantly, it added to the sense of exclusivity among the nightclub's clientele of seeing and being seen as each couple made their way around the dance floor.

The dance floor itself was parquet and laid in an intricate design of a compass rose encased by rings of diamond patterns within the parquet. Hanging above the floor were a series of concentric rings that gradually recess into the ceiling before a dome balloons back toward the floor. In the very center suspended by a brass pole is one of four chandeliers by Edward F. Caldwell & Co., which had a history of providing opulent fixtures for notable places like the White House and St. Patrick's Cathedral. For the Rainbow Room, Caldwell designed chandeliers composed of crystals in the shapes of prisms, balls, and stars — all meant to set a mood for Rainbow Room guests of a dreamy sky at nightfall.

The Rainbow Room's customers expected elite company

Although the Rainbow Room opened its doors in 1934 with a seemingly endless guest list of the New York elite class, it was a struggle to figure out exactly what the nightclub's clientele would be on a regular basis. Most of the country was suffering badly during the Great Depression, and the Roosevelts, the Astors, and the Rockefellers could only go so many times each week. Soon, according to Daniel Okrent's "Great Fortune," the club's management was forced to relax the dress code from "white tie" to tuxedos in the hope that they could attract people of means, even if they were not so-called dignified society people.

The policy change along with an active attempt to entice celebrities — not as performers but as guests — brought in new crowds of people. Soon, New York socialites were thrilled to be mixing with celebrities like Bette Davis, Joan Crawford, Laurence Olivier, and Marlene Dietrich. And Rainbow Room visitors witnessed Hollywood gossip firsthand when actress Ginger Rogers had a very public affair with millionaire Howard Hughes, sometimes at the Rainbow Room (pictured above). All of it added up to a level of success that John D. Rockefeller Jr. and the Rainbow Room's management hoped for, but struggled to find.

Every night was an all-night party

When you were making reservations for the Rainbow Room in the 1930s, you had to decide what kind of night you wanted to have: a nice night out, or a raucous time that had no end. That choice would determine whether you made a reservation for dinner service at 6:30 p.m. or supper service at 10:30 p.m.

Each night, the first seating began at 6:30 with an hour-long organ recital by Richard Leibert, the Radio City Music Hall organist during dinner, per a Rainbow Room program (via the Culinary Institute of America archives). Then it was time to hit the dance floor with the big band music of Jolly Coburn and his orchestra, which featured a rotating cast of vocalists. At 8:30 p.m., French diseuse Lucienne Boyer made her way to the entertainer's balcony for 30 minutes of seductive spoken word with piano. Rainbow Room guests were then treated to one more hour of dancing before being sent on their way at 10 p.m.

At that moment, the Rainbow Room crew had just 30 minutes to turn the space around and make it seem fresh for the second seating at 10:30 p.m. The program was nearly identical, but for this service, the hour-long organ recital was ditched, and visitors went straight to the dance floor for an alcohol-soaked night of fun. According to the program, a second round of dancing went from 12:45 a.m. to closing — an undefined time that went well into the early morning hours.

Dining at the Rainbow Room reached new heights

So-called "dining in the clouds" on the upper floors of New York City skyscrapers became the thing to do among New York City's social class in the 1930s. The Rainbow Room may not have been the first to offer skyline views at dinner, but it was perhaps the most spectacular for its combination of two-story views, first-rate entertainment, and an outstanding menu. Per a report from the New York City Land Preservation Commission, for a slightly more casual experience, the Rainbow Grille offered indoor and outdoor dining on the west end of the room. But most people were there for the full dining and entertainment experience of the main dining room, where they were seated at tables on tiered platforms that surrounded the dance floor.

The menu (via the archives of the Culinary Institute of America) was heavily influenced by French cuisine with a focus on seafood, and it oozed decadence. But the menu was also balanced by several American standards. Over a number of courses, you might have had turtle soup, snails Chablisienne, and frog legs and oysters Poulette, as well as stuffed celery, scrambled eggs and Irish bacon, and chicken salad. Desserts were also meant to impress. Pear flambe, cherries jubilee, baked Alaska, and boozy souffles were all on offer. Items ranged in price from $.25 to $2.50. Without cocktails, people spent on average about $3.50 for dinner at the Rainbow Room (approximately $75 in 2023).

Rainbow Room entertainment was second to none

If the Rainbow Room was to meet the promise of being more than just another restaurant, it would need to deliver a true nightclub experience. From moody ambiance to expertly made cocktails to dazzling entertainment, the Rainbow Room made good on that claim. On opening night, visitors were treated to organ music, songs by the Metropolitan Opera, and spoken word from French diseuse Lucienne Boyer, The New York Times reported the next day. Boyer left France for the Rainbow Room on a $ 6,000-a-week contract, per Time.

Boyer and a long list of future performers captivated Rainbow Room guests from what was known as the entertainer's balcony — an elevated space near the dance floor so all could easily view the performances. The balcony was flanked by two staircases that led down to the orchestra platform. Before long, according to Daniel Okrent's "Great Fortune," the Rainbow Room's clientele developed an appetite for entertainment off the beaten path. Management began booking animal acts, comedians, dancers, monologists, and impressionists. One night, ping pong champion Ruth Aarons was the top act. Visitors could challenge her to a match with a bottle of champagne as the prize. That was such a hit that a badminton team was put on the calendar.

The Rainbow Room views showcased New York's magnificence

Before the Rainbow Room even opened in 1934, the RCA building became known for its views because the observation deck and the upper floor terraces became available to visitors the year before. To say the views were panoramic was an understatement. As The New York Times put it, "From a single vantage point an observer could watch the boats in the Hudson and the harbor beyond the lower tip of the island; gaze at the Palisades far above the new George Washington Bridge; view the upper reaches of the Bronx, the hills rising behind the New Jersey meadows and the residential districts many miles away on Long Island."

When the Rainbow Room opened, all those same views were available to those inside but from the comfort of a plush seat and with a cocktail in hand (and without the risk of having your perfectly coiffed hair getting wind whipped). The 24 windows that were 24 feet tall wrapped around the 65th floor and were so impressively large that Time magazine didn't think of them as windows at all, referring to them as "high glass walls." At night, the views were even more dramatic. At the time, the journal Art & Decoration (via the Landmarks Preservation Commission) remarked, "All that separate the diner and dancer from the sky and the blinking towers of the buildings in the world are glass and the structure that supports it."

The Luncheon Club was popular (and highly problematic)

While the storied evenings and early morning hours of the Rainbow Room became part of New York City lore, what happened on the 65th floor during the day was just as interesting. According to The New York Times, first thing each morning, staffers transformed the space from swanky, moody nightclub vibes into the Rockefeller Center Luncheon Club, a members-only dining club for the Rockefeller Center businessmen. Diners selected items from a slimmed-down version of the Rainbow Room's expansive dinner menu. A more casual lunch might be a bowl of potato and leek soup with a club sandwich. But if you were there to impress a client or to land a new job, you might kick off a multi-course lunch with martinis and oysters.

The luncheon club was immensely popular and highly exclusive, with 600 members and a lengthy waiting list. According to the club's bylaws, it cost $75 a year for the membership, and prospective members needed approval from two members on the board of governors. However, the club's exclusivity also came with exclusionary practices. Women were forbidden membership to the club and were only allowed as guests in restricted areas. And, according to Daniel Okrent's "Great Fortune," Jewish membership was limited to 3.5%, based on the United States Jewish population.