How Policymakers Accidentally Made The Great Depression Worse

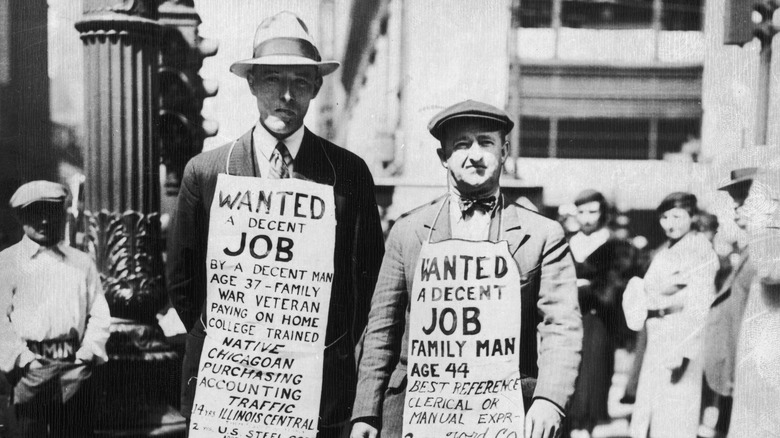

The Great Depression that began in 1929 was a global fiscal event that was worst felt in the U.S. and Europe. A multitude of factors played into what would be the severest downturn in U.S. history. However, it may be said that the failure of the Gold Standard to which the economy was tied was at the heart of the matter, leading to a 47% drop in industrial production and a nearly one-third decline in the country's gross domestic product (GDP). The result was panic in the financial sector, widespread joblessness, and horrifying poverty. Despite this, in 1937, it seemed as though the worst had passed. There were emerging signs of something resembling a recovery, with rising employment figures and increases in industrial output both contributing to a sense that the Great Depression was coming to an end.

However, there was more to come. Beginning in May 1937, the U.S. experienced another grueling downturn that would continue deep into 1938. And in retroactive analysis, many experts have concluded that the recession of 1937-8 was the fault of fiscal institutions attempting to battle the Depression — but making entirely the wrong decisions. Both the Federal Reserve Bank's monetary policies enacted at the time and the Roosevelt administration's mismanagement of the government budget contributed to rolling the clock back on economic recovery.

Policy errors in The Roosevelt Recession

The presidency of Franklin D. Roosevelt began in 1933, with the Democrats taking office in the wake of the stock market crash and promising to reverse the Great Depression that had emerged under the Republicans. In his first term, his administration's quick action on economic recovery during "The Hundred Days" after he first took office saw them gain widespread public support. It seemed that Roosevelt truly had a handle on ending the Depression.

Acting as secretary of the treasury, Henry Morgenthau Jr. spearheaded fundraising policies — like the instigation of a new Social Security tax — while also saving on costs by cutting bonus payments for war veterans. At the same time, the Federal Reserve doubled reserve requirements, taking on reserves from American banks. Soon, the signs of recovery seen in the previous months began to falter, and while the Federal Reserve urged the government to start spending to stimulate economic growth, the treasury sought to balance the budget and continued tightening its purse strings. The recession that followed deeply damaged the public perception of the Democrat government and was named in some corners the "Roosevelt Recession."

Some experts have since questioned the received wisdom that the decision of policymakers from the Federal Reserve to double reserve requirements truly contributed to the ensuing downturn, with a microeconomic analysis conducted in 2011 by the National Bureau of Economic Research suggesting otherwise.

The war that cured the depression

While many economists at the time were banking on the Great Depression coming to an end sometime in the late 1930s, the impact of the 1937-8 recession on the U.S.'s economic recovery meant that resetting the nation's finances would be a longer job.

The policy of recovery that had characterized the early part of Franklin D. Roosevelt's tenure, the New Deal, began to run out of steam in the aftermath of the 1937-8 recession, which saw the economic capabilities of his government questioned. Nevertheless, Roosevelt oversaw a vast spending drive in the final months of 1938 that sought to banish the specter of recession in the years that followed.

In fact, it would take the seismic events of World War II to finally put things back on track. Starting with the Lend-Lease Act of June 1940, the U.S. dedication to the selling of arms to European allies like as the U.K. and, later, its involvement in the war itself led to what The American Prospect's Doris Goodwin describes as an "economic breakthrough," with the creation of around 17 million new jobs that cemented the young country as a true global superpower.