The Tragic Story Of Maya Kowalski And The Doctor Who Traumatized Her Family

Maya Kowalski was just 9 years old when she and her family's lives in Venice, Florida were turned upside down in 2015. Pains, sores, and contortions wracked her body, and neither her parents nor her doctors could figure out what was wrong. "Maya would be crying 24/7," her father, Jack, told People. A Tampa-based doctor finally made a diagnosis and put Maya on a treatment plan that seemed to bring her relief. But that same treatment plan helped plunge the Kowalskis into a nightmare when Maya relapsed in October 2016.

Staff at the Johns Hopkins All Children's Hospital in St. Petersburg grew suspicious of the drugs the family were requesting for their daughter. Dr. Sally Smith, medical director for Pinellas County's child protection team, suspected Maya's mother Beata of child abuse. The daughter and her parents were separated as an investigation looked into things, despite multiple warning signs that Smith's charge was doing more harm than good. The psychic toll of the accusation wore on Beata, who desperately sought some way to help and communicate with her daughter. In January 2017, Beata Kowalski died by suicide, not long before Maya was returned to her family's custody. In the years since, the Kowalskis have sought both justice and a platform to tell their story.

If you or anyone you know is having suicidal thoughts, please call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline by dialing 988 or by calling 1-800-273-TALK (8255).

Who is Beata Kowalski?

Beata Kowalski was originally from Poland before moving to Venice, Florida. Her husband, Jack, worked as a fire chief (he has since retired), and they had two children, Maya and Kyle. Beata worked as a home-care nurse and was therefore well-acquainted with ailing patients. But her daughter's initial symptoms were outside her area of experience.

Beata, whose English was imperfect, had a reputation for intensity. In her marriage, she generally took charge when it came to childcare. And when faced with a dilemma like Maya's increasing pain, Beata's habit was to dive into research and assertive advocacy for her child's care. A patient of hers led her to Dr. Anthony Kirkpatrick, who made a formal diagnosis of complex regional pain syndrome. But according to the Herald-Tribune, doctors and staff at Johns Hopkins All Children's Hospital were alarmed by her manner and suspicious of her mental health. Those initial suspicions led to the initial report of child abuse that drove the Kowalskis apart.

The family's attorneys contend that All Children's staff were dismissive of Beata, who was only trying to speak up for her daughter. And Dr. John Wassenaar, a family pediatrician, defended Beata and her relationship with Maya. "Although Beata Kowalski, as a registered nurse, had more medical knowledge than most parents, I saw nothing to indicate that she was anything other than a loving, caring mother," he wrote in an affidavit (via DocumentCloud).

What is complex regional pain syndrome?

Maya Kowalski's initial episode of pain was an asthma attack over the Fourth of July weekend in 2015. While in hospital for the attack, sensations of pain in her legs developed, eventually leaving her unable to support herself. Lesions appeared and her feet distorted. Causes initially considered for her symptoms included a side effect from steroids used to treat Maya's asthma, but no one made a diagnosis until the Kowalskis went to see Dr. Anthony Kirkpatrick, an anesthesiologist based out of Tampa. He concluded that Maya suffered from complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS).

According to the Cleveland Clinic, CRPS is a neurological condition, believed to be due to an immune reaction in some aspect of the nervous system after an injury. It typically affects adults and is more common in women than men. Common symptoms include increased sensitivity to pain, changes to the skin, hair, and nails, and loss of function in affected limbs. Treatment is designed to alleviate symptoms and improve quality of life, and many sufferers go into remission, but CRPS is incurable.

The exact causes of CRPS, and why it affects some who suffer injuries but not others, is unclear. There is some controversy over the condition itself; per the Herald-Tribune, some doctors consider it a mental state without underlying physical causes.

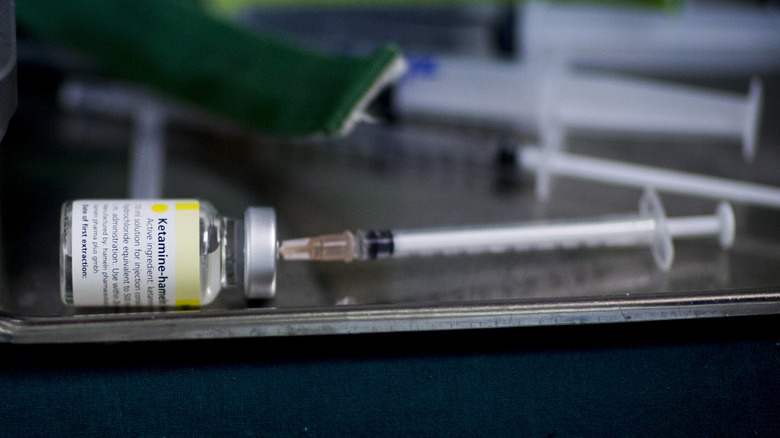

Why was Maya being treated with ketamine?

While diagnosing Maya Kowalski with complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS) gave a name to her ailment, it didn't bring any immediate relief. With CRPS being an incurable condition, treatments are aimed at relieving symptoms and restoring normal limb function (per the Cleveland Clinic). Maya was treated with oxygen and water therapy, among others, until Dr. Anthony Kirkpatrick, who diagnosed her, recommended using ketamine.

Per the DEA, ketamine is a powerful anesthetic that can also be used to induce hallucinations. Low doses of ketamine delivered through an IV infusion have been approved as a treatment for CRPS, and Kirkpatrick put Maya on an infusion schedule every three to four weeks. But when that didn't bring relief, he recommended that she undergo what's known as a "ketamine coma," a multiday procedure where a large dose of the drug is flushed into a person's body. At that level, the ketamine can effectively reboot the patient's nervous system (per People).

This procedure is still considered experimental and has not been approved for use in the United States. The Kowalskis took their daughter to Monterrey, Mexico to have it done in November 2015. She said that it brought her considerable relief, and after returning to the U.S., she and her family continued to rely on ketamine to treat flares of her condition before she was rushed to the hospital in October 2016.

The Kowalski's demand for ketamine made hospital staff suspicious

That Maya Kowalski suffered from complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS) was not disputed, even by the staff at Johns Hopkins All Children's Hospital in St. Petersburg who helped facilitated her infusions before October 2016. And her condition, while still leaving her in pain, had become manageable through ketamine treatment. But on the night of October 6, 2016, Maya suffered a terrible relapse and was rushed to the emergency room at All Children's (per The Cut). And it was while Maya was being treated at All Children's that doctors began having doubts about Maya's ailment.

Her mother Beata's insistence that Maya be treated with a ketamine dose of 1,500 milligrams alarmed ICU physician Beatriz Teppa Sanchez. It was a high dosage for an already strong drug. Beata also pushed for her daughter to be treated before routine tests like an ultrasound were performed. Teppa Sanchez found Beata's manner off-putting and felt that Maya's symptoms seemed to lessen when she wasn't around.

Such behavior, and disregard for procedure, can be a warning sign of parental abuse or neglect, but a formal notice about the Kowalskis filed by a social worker had already been rejected. Nevertheless, Teppa Sanchez passed on her suspicions to Dr. Sally Smith, medical director for Pinellas County's child protection team, who began her own investigation.

What is Munchausen syndrome by proxy?

The first report filed against the Kowalskis, made by social worker Debra Hansen, suggested parental neglect. Without supporting evidence, it was discarded. But a second report, filed after Dr. Sally Smith had already been called by ICU doctors, shifted its accusations. Based on the behavior of Beata Kowalski, she was suspected of harming her daughter Maya through overtreatment of her condition. Florida's Department of Children and Families accepted this report and formally asked Smith to investigate. She determined that Beata had Munchausen syndrome by proxy.

Formally known as factitious disorder imposed on another (FDIA) according to the Cleveland Clinic, Munchausen syndrome by proxy is a mental illness suffered by a parent or caretaker. They falsely claim that someone in their care is sick in order to generate sympathy for themselves, likely due to their own emotional issues. It can lead to the child or dependent being put through unnecessary and potentially dangerous medical procedures. It's most commonly found in mothers and is considered a form of child abuse when children are the victims.

Dr. Smith aggressively pursued cases even after warnings from other doctors

At the time she became involved in the Kowalski case, Dr. Sally Smith had decades of experience working with Johns Hopkins All Children's Hospital in St. Petersburg and had been the medical director for Pinellas County's child protection team since 2002 (per USA Today). She's been certified as a child-abuse pediatrician by the American Board of Pediatrics, delivered lectures on the subject, and has been spoken well of by some former colleagues. Her presence at All Children's was ubiquitous and her judgments were almost always heeded without question.

But Smith, who retired in 2022, also acquired a reputation for aggressively interpreting cases as child abuse, sometimes in an unprofessional manner and on little evidence beyond her personal assessment of a parent's behavior. While she maintains that she rarely erred over the thousands of cases she assessed, several families she implicated in child abuse have been shown to be falsely accused, from Ukrainian immigrants to "American Idol's" Syesha Mercado, and her name has been connected to lawsuits and appeals.

While investigating the Kowalskis, Smith was warned against rushing to a charge of child abuse. Dr. Aidan Kirkpatrick, who diagnosed Maya Kowalski with complex regional pain syndrome, told her it could cause serious harm to the family. Dr. Ashraf Hanna, who administered Maya's ketamine infusions, said that CRPS often resulted in misdiagnosed Munchausen syndrome by proxy. Smith disregarded both warnings in her recommendation that Maya be separated from her family.

Florida's privatized child welfare system has been criticized before

When investigating cases of potential child abuse at John Hopkins All Children's Hospital in St. Petersburg, Dr. Sally Smith was often taken by parents to be a member of staff; she dressed the part, and her ID badge had the hospital's logo on it. But Smith's real employer was Suncoast Center Inc., a private company partially subsidized by taxpayer money to manage Pinellas County's child welfare system.

According to the American Children's Campaign, Florida's decision to privatize its child welfare system came after years of disgraceful headlines. Under a state-run program, there were low adoption rates among foster children and a high rate of deaths. Government offices were converted into sleeping quarters due to a lack of beds. And there was a dramatic backlog of cases. To address the problem, the state legislature began the process of transferring child welfare to locally-managed community-based care (CBC), a process completed in 2005.

The state's track record has improved considerably, particularly in the area of foster care. But child protective services remains an issue. It remains under the auspices of the Department of Children and Families, an agency with ongoing management problems. State officials have acknowledged failures to safeguard children taken from their parents. And private entities like Suncoast have little transparency when it comes to their track record.

Maya was suspected of faking her illness

When her investigation into the Kowalskis formally began, Dr. Sally Smith's working assumption was that the mother, Beata, suffered from Munchausen syndrome by proxy and was inflicting needless medical procedures on her daughter Maya with a false claim of complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS). She filed a report to that effect on October 13, 2016, according to The Cut, and the state of Florida issued a shelter order soon after. It placed Maya in state custody, confined her to the hospital, and initially denied her parents any contact with her. While later amended to grant some visitation rights, the Kowalskis' time with their daughter could be arbitrarily limited by hospital staff, and Beata was still not allowed any direct contact.

One of the tests for Munchausen syndrome by proxy is such a separation, to see what effect distance from a parent or caretaker has on the child or dependent's health. Maya's pain from CRPS persisted well after Beata was banned from her side, but Smith remained unconvinced. On her orders, doctors began noting any instance where Maya used her legs and feet. Based on their findings, Maya was diagnosed with factitious disorder, a mental illness wherein a patient knowingly fakes an illness to get attention (per the Cleveland Clinic).

The new diagnosis didn't affect the shelter order against Maya's parents. Nor did it stop the hospital from continually billing the Kowalskis and their insurance for CRPS treatments, a bill that ran to $650,000.

Several legal points of Maya's care and investigation are suspect

According to The Cut, when the staff of Johns Hopkins All Children's Hospital wouldn't heed their daughter's care, Jack and Beata Kowalski wanted to take Maya out of the hospital. She was still in pain and not receiving the ketamine treatments that had worked for her in the past. But Maya's case was still being investigated by Dr. Sally Smith for potential child abuse. ICU staff warned the Kowalskis that discharging their daughter at that juncture was against medical advice and that such an act could lead to their arrest. But there is no law forbidding parents, or anyone, from leaving the hospital against medical advice.

The warning by ICU doctors wasn't the only legally suspect part of Smith and All Children's handling of the Kowalski case. Smith was able to access Maya's confidential medical records through the hospital's internal portal. It was how she learned about the family trip to Mexico for Maya's "ketamine coma." But as Smith was neither part of the hospital staff nor one of Maya's treating physicians, her accessing those records could be a violation of privacy under HIPAA (a charge Smith contests).

It also came to light that the social worker assigned to Maya, Cathi Bedy, had once been arrested and charged with child abuse herself. Maya claimed that, when she refused to let Bedy take pictures of her without her clothes on, Bedy forcibly removed her clothes and pinned her for the photos.

Beata was suspected of mental illness but had no prior history

According to the Cleveland Clinic, Munchausen syndrome by proxy is considered a mental illness. Even before Dr. Sally Smith assessed Beata Kowalski as suffering from the condition, staff at Johns Hopkins All Children's Hospital who interacted with Beata found her pushy, and her demands regarding her daughter Maya's care unsettling. When Smith shifted from assuming Munchausen-by-proxy to Maya's faking her own illness, hospital staff seem to have continued to regard Beata as mentally ill.

But Beata's husband Jack told The Cut that his wife had never been diagnosed with any mental illness. When Beata underwent a mandatory psychological evaluation after the state of Florida issued a shelter order against her, the conclusion was that she did not have Munchausen-by-proxy. If she was suffering from anything, it was from the stress of Maya's illness and the accusations of child abuse. The separation from her daughter was hard, and Maya's continued deterioration at All Children's was harder. Beata, who was denied any opportunity for direct contact with her daughter, thought Maya might be dying. She fell into depression and began drinking.

When Beata died by suicide on January 7, 2017, Smith and the hospital exchanged texts that suggest they saw it as a confirmation she suffered from mental illness. Beata left notes to her family and to the judge overseeing Maya's case, who returned Maya to her father's care shortly thereafter.

The Kowalskis have filed several lawsuits over their treatment

Maya Kowalski left Johns Hopkins All Children's Hospital in January 2017, not long after her mother Beata died by suicide. An assessment at Brown University helped confirm her diagnosis of complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS). She had lost weight in the hospital and could barely sit up unaided, but after two and a half years of exercise and physical therapy, she regained the ability to walk on her own. As is typical with CRPS, her pain has gradually declined (per The Cut).

Her family has filed several lawsuits over what happened to them. In October 2018, they acted against All Children's, Florida's Department of Children and Families, social worker Cathi Bedy, Dr. Sally Smith, and Suncoast Center Inc., the private company responsible for Pinellas County's child welfare system. Jack Kowalski, who worked as a fire chief before retiring, has said he isn't against the system set up for detecting child abuse; he encountered some of it in his career. "I just think it's got to be done a different way," he told The Cut.

In 2022, Smith and Suncoast reached a settlement with the Kowalskis to the tune of $2.5 million. After several delays, the suit against All Children's was scheduled to go to trial in September 2023.