The Most Mysterious Shipwrecks In History

We are fascinated by shipwrecks, and it's easy to see why. First, there's the idea of sunken treasure, which has a pretty universal appeal in any culture that admires shiny things (all of them). Then, there's the uber-creepiness of seeing the remains of a great ship languishing at the bottom of the ocean, covered with algae and "rusticles," a once-mighty vessel that's now a home for crabs and fish. Finally, there's the mystery. Ships sometimes sink, vanish, or are abandoned. When there are no survivors to tell the stories of these shipwrecks, eventually those lost ships become so mysterious and weird and creepy that they attain a sort of legendary status.

Why was the Mary Celeste abandoned when it was still perfectly seaworthy? What happened to the HMS Terror, and why would anyone name a ship after one of the most negative emotions in the human repertoire? These maritime mysteries may one day have plausible explanations, but we'll never truly understand what happened when these ships sailed away for the last time.

Oops there goes our perfectly seaworthy ship

On December 5, 1872, the Mary Celeste was found abandoned and in disarray 400 miles east of the Azores. One of its two pumps had been disassembled, its charts were scattered, and it had taken on about 3.5 feet of water, though it was still seaworthy. Its lifeboat was missing and its cargo of 1,701 barrels of industrial alcohol had been left behind.

The fate of the Mary Celeste's crew has been a mystery ever since. According to Smithsonian, theories range from the ridiculous (sea monsters) to the plausible (mutiny and pirates). Fortunately, the human race is mostly more rational than it used to be, so we can rule out sea monsters pretty much offhand. Because the cargo was intact, we can also rule out pirates, unless they were seriously inept pirates. So what happened to the Mary Celeste?

A 2002 investigation may have found some information. The sea had been stormy, and only one of the Mary Celeste's two pumps was operational, which means it would have been difficult for the captain to know how much water his ship had taken on. The log noted they were in sight of land, so it seems logical, if there was uncertainty about whether the ship would float or sink, that an abandon ship order would have come at that time. That doesn't explain what actually happened to the crew after they abandoned ship ... but it's a start.

If you name your ship 'Terror' you can probably expect bad things to happen

According to AMC, the HMS Terror was taken out by a giant supernatural polar bear or something, which is probably not true since according to AMC the whole world was also taken out by a virus that reanimates corpses and makes everyone have really greasy hair all the time.

If you just ignore the part where someone chose the stupidest name ever for this ship. (Terror was formerly a bomb ship, so perhaps the name once fit, but if you're going to then go explore the Arctic maybe you should consider coming up with a less doomsy-sounding name, like the HMS Got Home Safely with Everyone On Board.) Anyway Terror was sailing with another former bomb vessel called HMS Erebus, which can mean "limbo between Earth and hell," so same basic problem.

According to the Washington Post, both ships set sail in 1845 and never returned. The local Inuit said the ships became trapped in ice, and the starving men finally resorted to cannibalism. Still, no trace of either vessel was discovered until divers identified Erebus in 2014 and Terror in 2016.

Before that, there were clues — human remains found on King William Island had hack marks on them consistent with cannibalism. A note found nearby said the men were going to walk to the Canadian mainland, nearly three years after the ships vanished. Beyond that, well, we can be reasonably certain it wasn't demon polar bears. So there's that.

Let's just say it was pirates

If there's one sort of story that we humans can almost universally get behind, it's pirates. Two hundred years ago, people also liked stories about damsels in distress being captured by pirates, though today we mostly prefer to watch badass damsels butt-kick their way out of distress.

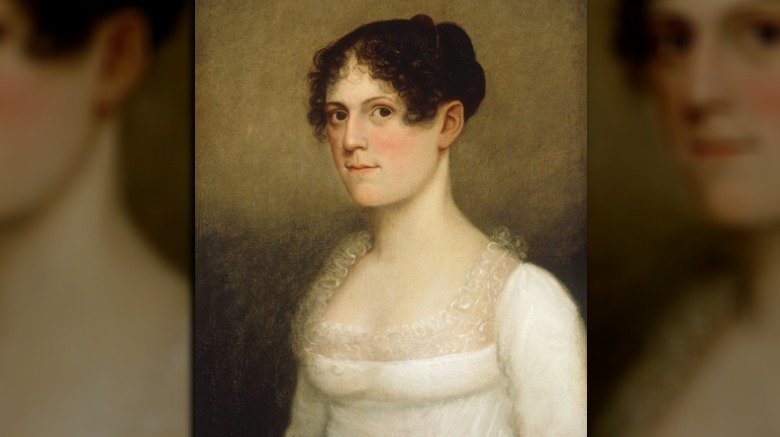

Theodosia Burr Alston was no ordinary damsel in distress — she was the daughter of former vice president Aaron Burr, who had the dubious distinction of having killed Alexander Hamilton in a duel and also of trying to convince several states to secede from the Union so he could become emperor. According to North Carolina Shipwrecks, Theodosia was en route to visit her infamous father when her ship, the Patriot, disappeared.

First, there was the theory that the Patriot sunk during a gale, but that's boring. Next, there was a theory that it had been captured by pirates. Then the deathbed confessions started rolling in. If one were to believe all of them, the Patriot was lured into the rocks by "wrecking pirates," who killed everyone on board and scrapped the ship. And Theodosia was also washed up dead and buried on a farm, and she also died in the arms of a Karankawa chief who rescued her from the wrecked ship, and she also walked the plank after the Patriot was captured by pirates. Who should we believe? Theodosia has been dead for 200 years, so at this point, maybe just pick the best story and roll with it.

The ship that rolled over and died

If you've never actually visited the Great Lakes, it might be hard to imagine that so many doomed ships could have sailed there. After all, lakes are not oceans, but rather places where you jet ski and drive around in overpriced speedboats blasting music no one else wants to listen to. The Great Lakes are not typical lakes, though. Lake Superior has a surface area of 31,700 square miles and is 1,333 feet at its deepest point. During a storm, waves on the Great Lakes can reach heights of more than 20 feet.

The SS Cyprus was an ore ship that sank on Lake Superior on October 11, 1907. According to The Shipwreck Museum, Cyprus was only 21 days old when it rolled over in a moderate gale and sank, leaving only one survivor. The cause of the wreck is still not known, but there are some tantalizing clues: The day before the ship was lost, a passing steamer noted it was leaving a red wake, which is something that might happen if water mixed with iron ore and then leaked out through a damaged hull.

In August 2007, Cyprus was discovered in 460 feet of water roughly 10 miles from where it was supposed to have sunk, but the wreck hasn't really offered up much insight into its own demise. And that surviving crew member was no help, either — after the wreck he never spoke openly about the Cyprus again.

This wreck was carrying an ancient computer

The only thing cooler than a shipwreck is a much, much older shipwreck — and when there's a mystery hidden in its hold, well, that's even better.

The Antikythera shipwreck is more than 2,000 years old — it was discovered in the Mediterranean by sponge divers in 1901. Since then, archaelogists have recovered a ridiculously huge collection of artifacts from the wreckage, including jars, sculptures, jewelry, and the seriously bizarre "Antikythera mechanism," which is a mysterious steampunk-clockwork device used to track time and celestial objects.

Sometimes called "The World's First Computer," the mechanism today kind of just looks like a twisted blob of corroded metal, but in its prime it had thousands of interlocking teeth, 30 bronze gears, and a hand crank that made it come to life. It kept track of three different calendars, it noted the approach of the Olympic games, and it could also mimic the travels of each planet and the Moon. The technology used to build the Antikythera mechanism predates similar technology by at least 1,400 years. X-ray analysis has allowed archaeologists to look through the layers of corrosion to its 3,500-word inscription, which basically confirms the device's purpose as a teaching tool and status symbol.

According to the Washington Post, archaeologists have also recently discovered human bones in the Antikythera wreck, which means we may be closer to understanding where the ship came from and who its passengers were.

Not so victorious after all

The HMS Victory was only really briefly victorious — it was one of 17 ships returning to the U.K. after a triumphant 1744 mission against the French in Gibraltar and Lisbon. But then a storm came along and sent the Victory to the bottom of the English Channel.

The other 16 ships survived, but no one seemed to know the fate of the Victory. Some witnesses said it had been heard firing its guns in distress. Then pieces of wreckage started washing up on shore near Alderney.

That was bad news for the dude who ran the lighthouse because no one could imagine that a ship as mighty as the Victory could be lost unless it was someone's fault. According to The Telegraph, the lighthouse keeper was accused of failing to keep the lights on, and then he was court-martialed and vilified and probably went to his grave with people spitting on his coffin. Finally, in 2008, Victory's remains were found a full 60 miles west of Alderney, thus exonerating the lighthouse keeper more than 250 years too late.

So what did send the ship to the bottom of the sea? It could have been rotting timbers, or maybe the weight of 100 bronze cannons, or maybe the £128 million in Portuguese gold that was supposedly on board. If the ship is ever raised, we may get some answers. Or we may not. Sometimes the sea just doesn't like to reveal its secrets.

Mutiny on the Outer Shoals

The only thing cooler than a shipwreck is a much, much older shipwreck, and the only thing cooler than that is a ghost ship.

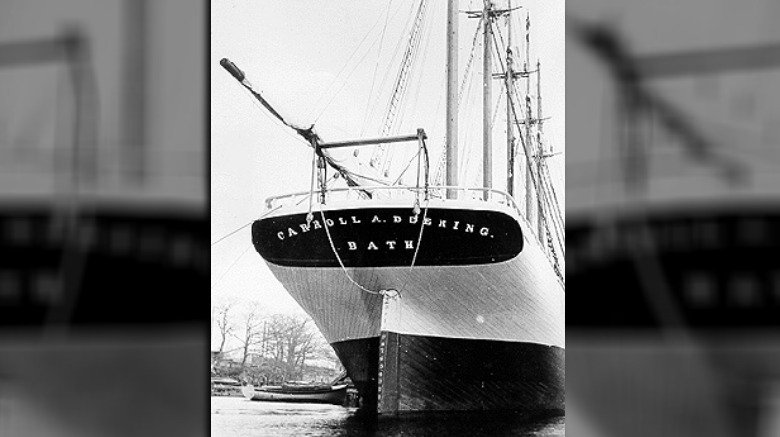

In 1921 the Carroll A. Deering sailed past the Cape Lookout Lightship, and a crewman told the keeper that the ship had lost its anchors. But there was a funny thing about the dude who passed along the message: He didn't really look like an officer and he didn't really act like one either, which left the lightship keeper with an odd feeling. The next day, the ship was seen by the SS Lake Elon. By the following day, it was aground and abandoned on the Outer Shoals. The sails were set, the lifeboats were missing, and there was food on the table as if the crew was just about to sit down for a meal.

This story even has a message in a bottle. According to the National Park Service, a note was discovered floating in a bottle that seemed to point to pirates as the culprit, but the note was later proven to be a hoax.

Interestingly, a lot of stuff was missing from the ship, and the report of the crew member who "didn't act like an officer" has led some to speculate that the crew mutinied, ran the ship aground, and took everything of value. But since the Carroll A. Deering was scrapped shortly after the incident, no evidence remains that could ever confirm or deny that theory.

The ghost ship that sailed the Arctic for decades

People have been seeing the Flying Dutchman since 1641, but it's pretty doubtful that it ever had a real physical presence on the sea, at least not as a bona fide ghost ship. It was just a story, perpetuated by Frederick Marryat's 1839 novel The Phantom Ship and popularized by Captain Jack Sparrow. Still, real ghost ships have existed, though most of them, like the Carroll A. Deering and the Mary Celeste are eventually boarded, hauled off, and either scrapped or refitted.

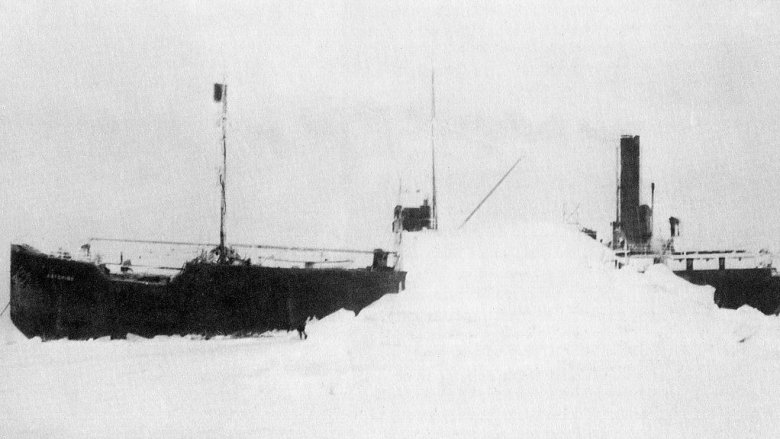

In October 1931, the Baychimo was near Barrow, Alaska, when it became trapped in the ice during a storm. In those modern days being stranded in ice wasn't as harrowing as in earlier days — thankfully, no one was eaten by a demon polar bear and no one had to resort to cannibalism. Instead, Historic Mysteries says half the crew was airlifted away while the other half decided to wait out the bad weather. Then a blizzard blew in, and the ship vanished.

But that wasn't the end of the Baychimo. A few days later, the ship was seen drifting 50 miles south of Barrow. The crew managed to retrieve its cargo, but it looked like it was destined to sink, so they abandoned it. But Baychimo didn't sink, not for at least another 38 years. The ship was repeatedly seen drifting until 1969, when most people think it finally succumbed to the elements.

The most-found shipwreck in the Great Lakes

Several thousand ships have been lost in the Great Lakes since 1679, starting with Le Griffon. According to Live Science, Le Griffon was owned by French explorer Rene-Robert Cavelier de La Salle, who ran out of money and left the ship in the hands of its crew, hoping they could pay off his debts with income from the fur trade.

When La Salle finally returned to Lake Michigan in search of his ship, he encountered the Potawatomi tribe, who told him that Le Griffon had sailed off in stormy weather, never to be seen again. As proof, the Potawatomi presented La Salle with a few pieces of the wrecked ship and some moldy beaver furs.

Since then, close to 30 different explorers have claimed discovery of Le Griffon, making it the butt of a shipwreck joke: It's the most searched for, and the most found shipwreck in the Great Lakes. (Most of the discoveries don't even turn out to be ships.) One recent discovery was made in 2014, but even though the remains do appear to be from a very old, wooden ship, there's no definitive proof that it's Le Griffon, either. It might just be a scrapped tugboat.

Many divers like a different Le Griffon site also discovered in 2014 — some say they've seen the shadow of a large ship pass over the wreck site, even when there are no ships in the area. So let's just call this one Le Griffon! Haunted shipwreck stories should get extra points.

And you thought pirates only existed in Disney movies

No list of shipwrecks can be complete without sunken treasure. In 2007 a treasure hunting outfit with the very misleadingly science-y name "Odyssey Marine Exploration" announced it had recovered 17 tons of gold and silver from a sunken wreck off the coast of Cornwall.

Odyssey refused to publicly speculate on exactly which shipwreck they were plundering — instead, they code-named the find the Black Swan. According to The Guardian, though, a squabble with the Spanish government the following year seemed to suggest the ship was a Spanish galleon, possibly the Nuestra Senora de las Mercedes, which was full of Peruvian treasure when it went down in 1804.

When Peru got wind of this, it decided the loot actually belonged within its borders because the coins were all minted from metal stolen by the Spaniards. And then Odyssey claimed the treasure, and Spain claimed the treasure, and marine archaeologists grumbled that it all really ought to go in a museum. By 2012 the issue was finally settled in Spain's favor, though Odyssey continued to argue that they just couldn't be sure the ship was really the Mercedes, so that meant they were the rightful owners. Unfortunately for Odyssey, most of the coins are now in Spanish museums, so victory goes to the marine archaeologists.