Why Ancient Egyptians Would've Felt Right At Home Playing Dungeons & Dragons

Ancient Egyptians: builders of the Pyramids at Giza, creators of one of the oldest and most venerated civilizations on Earth, makers of the finest mummies, and ... hardcore tabletop role-playing gamers? Maybe not quite. But if you took a random Egyptian circa 304 to 30 B.C.E. and placed them around the table at a current-day "Dungeons & Dragons" session, they must just shrug and reach for the nearest d20 die without knowing any of the rules. Reason being? Ancient Egyptians were using 20-sided dice way before Gary Gygax and David Arneson created "Dungeons & Dragons" in 1974.

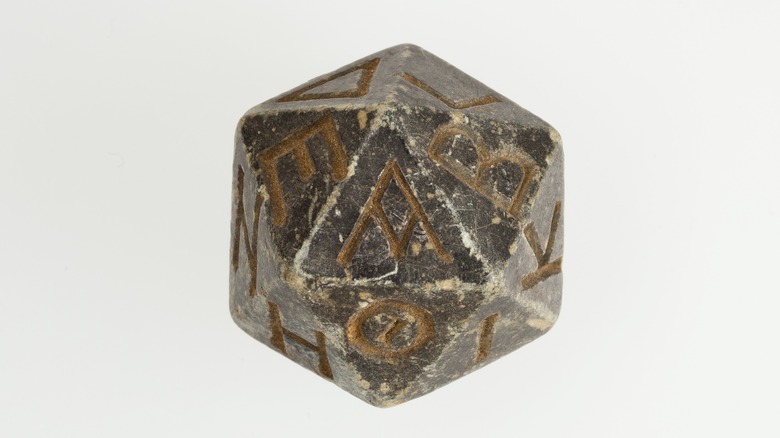

The Metropolitan Museum of Art has in its possession a number of polyhedral dice — dice with different numbers of faces — that date back thousands of years to the time of the ancient Romans, Greeks, and Egyptians. The oldest of them isn't one of those standard d6 (six-sided die) that folks use with Parcheesi — it's a d20, or an icosahedron. D20s are also the staple dice in "Dungeons & Dragons," rolled to determine the outcome of some of the game's most critical choices. Maybe you roll a 5 and don't grab ahold of the cliff as you fall. Bye, bye, Lawrence the Thief — nice knowing you. Maybe you roll a 19 with a Vorpal Blade and slice the head off a rabies-infected Minotaur — a sad moment, but necessary. In other words, d20s are implements of fate. And to the ancient Egyptians? It seems they held the exact same function.

A fusion of Greek and Egyptian

Granted, if an ancient Egyptian rolled a d20 at a modern game of "Dungeons & Dragons," the person wouldn't be able to read the Arabic numbers (1 through 20) on the die. Such a person would, however, be able to read the Greek letters inscribed into the ancient Egyptian die at the Metropolitan Museum of Art — alpha, sigma, gamma, tau, epsilon, lambda, etc. This is because ancient Greeks used their letters as numbers. Folks nowadays use those same letters/numbers in everything from nuclear physics to military callsigns and college fraternity names.

But why would an ancient Egyptian die be inscribed with Greek numbers to begin with? Well, the d20 in question dates all the way back to Egypt's Ptolemaic Dynasty (305 to 30 B.C.E.), the final dynasty of Egypt. The Ptolemaic Dynasty was ruled by a line of Macedonian Greeks who ended in the famed Cleopatra, and started with the death of Alexander the Great, who died in 323 B.C.E. Alexander conquered all the way from Macedonia down into Egypt, where he established the self-named city of Alexandria to cement his power and spread Greek culture. This was a time of immense cross-cultural pollination between nations across the Mediterranean and throughout the Middle East, including language exchange, as World History Encyclopedia explains. So even though the ancient d20 in question is technically "Egyptian," its use might have been copy-pasted from the Hellenistic Greek-speaking world.

[Featured image by the Metropolitan Museum of Art via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled | CC0 1.0]

Games, prophecies, and fate

The Metropolitan Museum of Art explains that the d20 die in question is the exact kind of polyhedron we use today. There's a Greek letter on each of the 20 faces, and it's about the same size as a modern 20-sided die: 3.2 centimeters tall, 3.8 centimeters long, and 3.4 centimeters wide. It's not made out of plastic, however, but serpentine, which is a kind of not-too-valuable, dull green, waxy-looking gemstone.

Barring the discovery of a player handbook, we can't say exactly how ancient Egyptians used 20-sided dice. We do know that they were used for games and religious rituals, though. The placement of the Greek letters/numbers on the ancient d20 resembles that of astragals, a type of game Egyptians played by throwing knucklebones. Later, similar dice were written in Demotic, not Greek — Egypt's non-hieroglyphic cursive script — and related to which deity someone ought to pray to for advice. As the Met says, the 2nd- and 3rd-century C.E. Greek book the "Sibylline Oracles" even outlines how various patterns of d20 rolls relate to standard question-answer pairs given by oracles to folks visiting holy sites. "So just like our game," "Dungeons & Dragons" players might say.

When ancient Rome came to power, it absorbed loads of traditions from other cultures into its empire, especially Greek. In 2003, Christie's sold a 2nd-century C.E. Roman d20 made of glass at auction for $17,925. And so the great, millennia-long tradition of games and fates continued.