The Dark Reason Early 20th-Century Dance Marathons Were So Popular

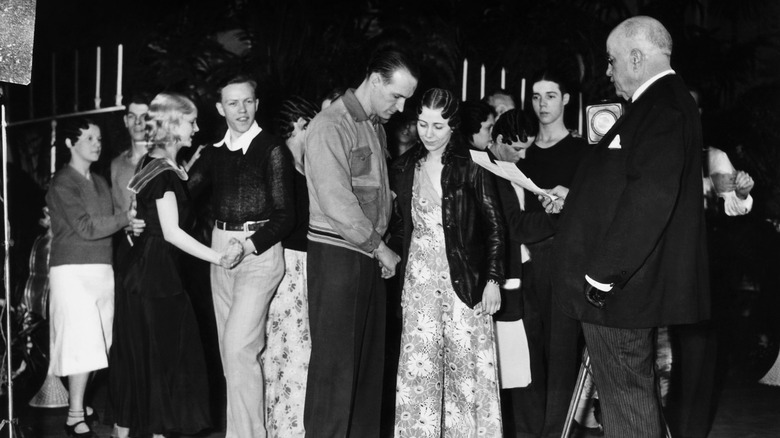

In the 1920s and 1930s, it wasn't unusual to watch exhausted couples shuffle around the dance floors of American cities for weeks and sometimes even months on end without a break. The dancers pushed their bodies to the limit for a chance at a cash prize or in the hopes of breaking into show business, according to JSTOR Daily. During the height of the dance marathon craze crowds sat watching their favorites from the stands. Like today's reality TV shows, fans had their favorites, who they rooted for. They would sometimes toss coins to their favorite couples, per the Omaha World-Herald.

The Chicago gangster Al Capone had a favorite couple he bet the equivalent of more than $177,000 on to win during a Chicago event that by December 30, 1930 had been going on for more than 3,000 hours straight. Capone even paid for a doctor and nurse to be on hand, at least until his couple won. But many who attended these events, which were termed "walkathons," weren't there to cheer on their favorite couple. They were there to see them suffer.

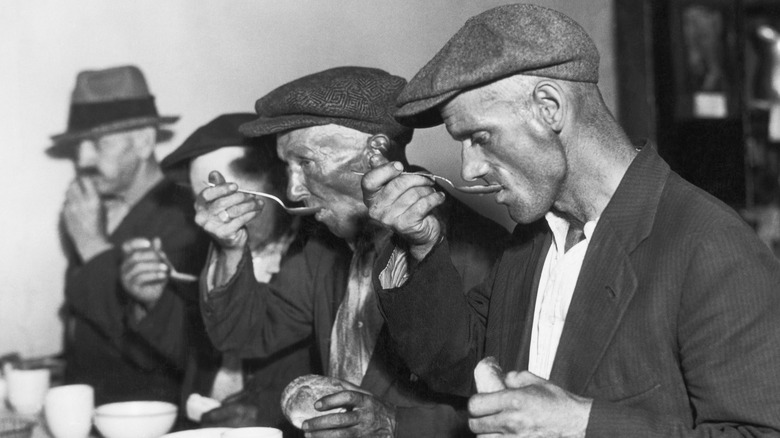

Desperate dancers

What began in the 1920s as an endurance fad like flagpole sitting, would become by the next decade — when Americans suffered during the Great Depression — a desperate way for some people to try to earn money or at least get a meal and temporary shelter. For the fans, it was cheap entertainment with the typical entrance fee being 25 cents — less than $5 today — to sit for as long as they wanted watching the couples holding each other up so their knees didn't hit the floor, which would end their chances at the prize money.

"Customers at a dance marathon do not have to be prepared for their excitement," the noir crime writer Horace McCoy pointed out in his 1935 novel "They Shoot Horses Don't They?" "When anything happens they get excited all at once. In that respect a marathon dance is like a bullfight."

Big business

By the 1930s, dance marathons were big business with strict rules and included a mix of locals and semi-professional dancers who traveled the circuit, per History Link. Among the regulations, the contestants had to be moving for 45 minutes out of every hour, 24 hours a day, plus participate in other events like foot races, according to "Dance of the Sleepwalkers: The Dance Marathon Fad."

One of the promoters, Richard Elliot (via JSTOR Daily), said the spectators "came to see 'em suffer, and to see when they were going to fall down. They wanted to see if their favorites were going to make it." Many deemed these events immoral or at least dangerous to the contestants. Authorities in Chicago tried their hardest to shut down the 1930 dance marathon using the Riot Act as the justification, but to no avail. By the mid-1930s, 24 states had banned walkathons, according to the Daily Mail. By World War II they had become a relic of the past.