The Most Famous Ninjas In History

Disentangling fact from legend can be a tall order when looking at many people, groups, and events throughout history; when it comes to ninjas, it's nearly impossible. Ninjas have become a ubiquitous presence in their customary black outfits (largely derived from 19th-century portrayals). They're an easy Halloween costume, a popular figure in comics, film, and video games, and an inexplicable opponent to pirates in internet memes. In Japanese folklore, they were said to hold supernatural powers that aided them in fantastic strikes against their opponents. But the historical ninja could be more accurately called the assassins and spy networks of their time.

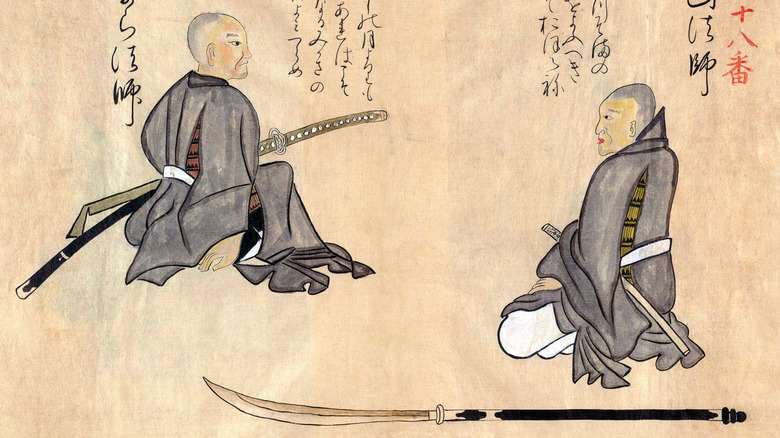

Clashing warlords had plenty of need for such services during the Warring States Period. Ninja as organized clans and forces developed in the Iga and Kōga regions (per John Man's "Ninja: 1,000 Years of the Shadow Warrior"). The most prominent clans (ikki) were commanded by family patriarchs (jonin). Ninjutsu as a distinct martial art — albeit one that stressed deception, loyalty, and disguise over any particular fighting prowess — followed, becoming established by the Edo Period. Before the unification of Japan under the Tokugawa shogunate, ninjas were held in low esteem but were in high demand for infiltrating enemy territory, gathering intelligence, and covertly murdering opponents.

Spies of any sort lose their value the more is known about them. Many ninjas were anonymous, and many famous names associated with ninjutsu may well be fictitious. But there are remarkable — and authentic — ninjas to be found in history books.

Hattori Hanzo

Ninjas have been presented as the dark mirror of Japan's samurai class. The latter were idealized as paragons of chivalry and martial prowess, the former used but scorned for their deceptions. Espionage, assassination, and guerilla warfare ran counter to the proud, declaratory image of the samurai. But it was the samurai and their lords who employed ninjas in their wars, and the majority of ninjas came from the samurai class.

Hattori Hanzō was one such ninja. According to John Man's "Ninja: 1,000 Years of the Shadow Warrior," Hanzō was initially a samurai in the service of Oda Nobunaga, the daimyō (feudal lord) who began the process of unifying Japan in the 16th century. He later took part in the Iga Revolt against Nobunaga and fell into service with Tokugawa Ieyasu, whom he led to safety through Iga after Nobunaga's assassination. Hanzō served Ieyasu to the end of his days as head of the Iga ninjas. Gardeners in peacetime, they made effective and deadly scouts, spies, and bodyguards when the need arose.

Hanzō's personal exploits, which included passing himself off as a dead rival ninja leader to mislead enemy forces, earned him the nickname "Devil Hanzō." But he wasn't so fierce that he wouldn't refuse to help Ieyasu's son commit suicide out of loyalty and affection. Hanzō died in 1596, supposedly while confronting ninja-turned-pirate Fuma Kotaro on Ieyasu's orders.

Kirigakure Saizo

Fact and fiction have become so well-blended in accounts of many ninjas that a complete separation of the two isn't possible. So it is for Kirigakure Saizō. Years of folk tales and children's stories have made him the equivalent of Zorro or a Western cowboy hero in Japanese culture. He's been incorporated into the Sanada Ten Braves, a group of particularly fearsome ninjas who supposedly served the samurai Sanada Yukimara at the end of the Sengoku era. But the real Saizō's fame seems to rest on a failed assassination attempt, and just what he did and how he failed is unclear.

It's generally agreed that Tokugawa Ieyasu ordered Saizō to take some action against Toyotomi Hideyoshi, Ieyasu's chief rival for Oda Nobunaga's legacy of unification. In one version of the story, presented by Stephen R. Turnbull in "Warriors of Medieval Japan," Saizō managed to enter Hideyoshi's home and slip underneath the floor. But before he could strike, a guard pinned him to the ground with a spear, and another ninja put a flamethrower to him.

Another version of the story paints Saizō in a less flattering light. As recalled by Donn F Draeger in "Ninjutsu: The Art of Invisibility," Saizō was a spy, not an assassin, and he gave away his own location on the floor by not using mosquito repellent. The buzzing of insects above him let the guard stab him through the shoulder, which ironically ensured that Saizō was taken captive instead of killed.

Tomo Sukesada

A textbook example of what real ninjas were capable of can be found in the life of Tomo Sukesada, leader of the ninja clan based in Kōga. He was another ninja in the service of Tokugawa Ieyasu, and at a crucial time during the wars of the 16th century. According to Stephen R. Turnbull's "Warriors of Medieval Japan," Ieyasu wanted to shift his loyalty to Oda Nobunaga after the death of his lord, Imagawa Yoshimoto, but Yoshimoto's son Ujizane held Ieyasu's wife and son hostage to ensure his continued devotion to the Imagawa cause.

In 1562, Nobunaga proposed that an exchange of hostages could be made if Ieyasu could take the Imagawa stronghold of Kaminojo castle. But the castle would be difficult to take in an open attack, and only with a heavy cost. Ieyasu was advised to reach out to Sukesada, who could muster 80 men. Under cover of darkness and dressed like the enemy garrison, they surrounded and infiltrated Kaminojo. They killed Imagawa men with such stealth that it was first thought that there was betrayal from within. When they were done, the ninjas put the castle towers to the torch, claiming 200 lives in the process.

Sukesada is said to have personally claimed the head of the fleeing castellan, while his men took valuable hostages. Ieyasu was slow in expressing his gratitude, but eventually wrote a letter of thanks and congratulations that is still kept in Kōga.

Sandayu Momochi and/or Nagato Fujibayashi

While researching his book "Ninja: 1,000 Years of the Shadow Warrior," John Man was told a story about the siege of Takino Castle by the forces of Oda Nobunaga. Among those in Nobunaga's camp were three ninja chiefs: Hattori Hanzō, Sandayu Momochi, and Nagato no Kami, also known as Nagato Fujibayashi. Man noted that Hanzō and Momochi were legendary names in Japan, but that there was almost nothing known about Nagato, other than his name in connection with the siege.

It was good business on the part of ninjas to maintain anonymity, but there may have been another reason for Nagato's obscurity. It's been suggested that Nagato Fujibayashi wasn't a real person, but a pseudonym used by Momochi. This, it is held, was in keeping with the art of yomogami no jitsu, the maintaining of multiple disguises to confuse enemies. Momochi allegedly carried this so far as to have two bands of ninjas, one under his own name and one under the guise of Nagato, that directly competed with one another. For good measure, he was said to have three distinct marriages and households.

The Nagato name disappears from records after Nobunaga turned against the ninjas of Iga, in part due to their alliance with Buddhist priests. Momochi, on the other hand, was recorded as fighting bravely, and no records exist as to his death. Two of his three homes (under his own name) still stand today.

Mochizuke Chiyome

The general lack of verifiable facts about historical ninjas goes double for any who also happened to be women. Patriarchy was well in force during Japan's feudal period, and the lives and achievements of women were rarely recorded in any detail. While women were trained in ninjutsu, only one such woman has seen her name and reputation survive to any appreciable degree: Mochizuki Chiyome. And precious little about her, beyond her existence, can be confirmed.

It's probable that Chiyome was descended from a Kōga ninja leader named Mochizuki Izumonkami, who built a fortified medical house that remains standing to this day. According to Metropolis Japan, she married another descendant of Izumonkami's before being widowed in 1561. After that, she was taken in by the daimyō Takeda Shingen, who made extensive use of ninjas in his campaigns. He saw the value in having women among his agents and installed Chiyome as the head of an intelligence network, possibly up to 300 strong, drawn from women who sought refuge in camps and foster homes.

Chiyome's ninjas, also known as kunoichi, gathered intelligence and spread disinformation while disguised as geisha, servants, and holy women. Contrary to later embellishments, it is unlikely that these ninjas were used in combat. And Chiyome's ninjas, while sheltered from war in her camps, likely weren't given a choice as to their occupation. Their fate, and Chiyome's, remains unknown.

Ishikawa Goemon

At what point does a thief become a dashing and heroic highwayman? The earliest historical records that exist put Ishikawa Goemon down as a bandit, nothing more. Centuries of folklore, theater, and film have made him into a Robin Hood figure, a champion of the poor and the enemy of authority. Along the way, he acquired a reputation as a ninja to boot. Never mind the lack of documentation for his being a ninja, or the conflicting accounts of how and in what direction the career path from ninja to bandit went. If, unlike Robin Hood, Goemon can at least be confirmed as having existed, his life story is just as varied as the many legends around his Western counterpart.

One version of Goemon's story (via Andrew Adams' "Ninja: The Invisible Assassins") puts him down as turning bandit after a failed assassination attempt. Supposedly, he targeted Oda Nobunaga himself, managing to get into his house and hide in the attic over Nobunaga's bedroom. He tried to poison him by dropping poison down a thread hung from the ceiling over Nobunaga's mouth, but Nobunaga was somehow alerted to the attempt and escaped. In this story, Goemon became a thief after the ninja clans were forcibly broken up.

Other stories claim that Goemon served in the Momochi clan of ninjas and went criminal when he couldn't cut it in legitimate lines of work. The stories generally agree that when he was finally captured, he was boiled alive.

Fuma Kotaro

In the 2000s, the internet was rife with memes pitting ninjas against pirates, and debates of varying degrees of facetiousness asked who would win in a fight between the two. For anyone who took the question seriously, the answer is simple: Encounters between ninjas of the Warring States Period (the 15th and 16th centuries) and Anglosphere buccaneers from the Golden Age of Piracy (the 17th and 18th centuries) were impossible. But within Japanese waters, ninjas not only tangled with homegrown pirates, but turned pirate themselves.

Fūma Kotarō was a leader of the Fūma ninja clan, known for their continuous and effective harassment of the forces of Tokugawa Ieyasu by sea. Their methods included spreading a film of oil over the surface of the water around enemy ships while ninjas swam below and disabled their rudders. Once his men were free, Kotarō would have the oil lit on fire. Another tactic saw men come ashore to practice guerilla warfare against enemy camps, using their own battle cries against them, attacks so effective that Kotarō's opponents sometimes slaughtered each other. He gained such a fearsome reputation that some thought him a monster, or at least subhuman.

According to Joel Levy's "Ninja: The Shadow Warrior," Kotarō became a pirate after the Tokugawa shogunate united Japan. Supposedly, he killed Hattori Hanzō and his men when they were dispatched by Ieyasu to bring him in, dead or alive. If true, in that encounter at least, pirates won the day.

Kato Danzo

Ninjas were sometimes alleged to have supernatural powers, and Katō Danzō's reputation largely rested on his purported sorcery. Some of his feats, like swallowing a live bull whole in front of 20 people or making an entire tree grow from a seed in minutes, can be chalked up to hyperbole. His manipulation of people through hypnosis is an anecdotal claim. But there is some documented basis for the stories that he could fly, stories that won him the nickname Tobi (Flying) Katō.

Danzō convinced friend and foe alike that he could fly through a simple deception, though when and against whom it was perpetrated vary in the telling. According to one account, described by Joel Levy in "Ninja: The Shadow Warrior," Danzō knew that a house he wanted to break into was prepared for him. As a distraction, he dressed a dummy in his clothes and threw it over the garden wall. The dummy was on a rope, so that Danzō could swing it about. His enemies took it as Danzō himself, flying about in the garden.

Danzō's reputation is supposed to have contributed to his downfall. After capturing a halberd and a servant girl on behalf of the daimyō Uesugi Kenshin, Danzō came to be seen as a threat by his master. He defected to the service of Takeda Shingen, but he fell under suspicion again. This time, his tricks did not avail him; Danzō is said to have died at Shingen's hands.

Tateoka Doshun

For all the mystery surrounding ninjas, the techniques they employed in committing espionage, sabotage, and assassination could be so simple that they might be taken as comedy or farce, if put into a story or movie. One such trick was known as bakemono-jutsu, or "ghost technique." A sinister-sounding name when translated, but what it really was, was imitating the enemy by disguise.

One of the most famous uses of bakemono-jutsu was the destruction of Sawayama Castle in 1558. According to Stephen R. Turnbull's "Warriors of Medieval Japan," the castle was held by a certain Dodo, a retainer to daimyō Rokkaku Yoshikata who went rogue. When a siege couldn't drive Dodo out, Yoshikata turned to ninjas. He enlisted Tateoka Doshun, a mid-level commander, who mustered 44 ninjas from his own Iga clan and four from Kōga. Rather than attempt any surreptitious penetration of the castle, Doshun led his men in through the main gate.

He did this by putting the mon, or emblem, of Dodo's men on the lanterns of his ninjas. Thus deceived, the garrison gave them entry, whereupon they promptly set the castle on fire. In the confusion, no one realized that the new recruits were aligned with Yoshikata. After the ninjas had done their job via bakemono-jutsu, the daimyō led his personal forces in an assault on the castle.

Jinichi Kawakami

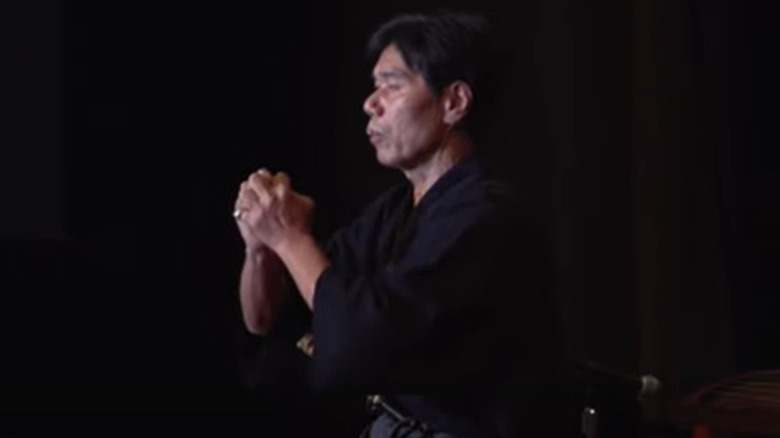

Ninjas, or at least large and well-organized clans of ninjas, lost their value to Japan's feudal lords in the long and peaceful Edo Period. But the practice of ninjutsu as a martial art endured. Texts on ninjutsu were prepared during this time, and schools in the Iga and Kōga regions handed down skills. Besides those directly related to espionage and murder, these included basic survival skills, map reading, and medicine.

In Japan today, very few claim to be authentic ninja masters. One of them is Jinichi Kawakami, described by the Ninja Museum of Igaryu as "the last living modern ninja" (Kawakami is an honorary director of the museum). He told the BBC in 2012 that his earliest introduction to ninjutsu came at the age of six, though he thought he and his master were only playing games. He was taught stealth, pharmacology, and explosives-making before being given a set of scrolls at age 18 and becoming the 21st head of the Ban family of the Koka clan. Ninjutsu isn't an all-encompassing passion with Kawakami, however; he works as an engineer.

Kawakami has some competition for the claim of last living ninja from Masaaki Hatsumi, who runs the martial arts group Bujinkan. But neither man intends to have anyone follow them as a designated master. So far as Kawakami is concerned, the ninja's time has passed, and there's no sense in carrying it on.