What Is Vodou And What Do Its Followers Believe?

Few religious systems have been as disparaged or as misunderstood as Vodou, a religion of the African diaspora which has a sizeable following in the Caribbean and beyond. B-movies such as 1932's "White Zombie" — considered the first zombie film — overtly linked the undead creatures to voodoo and supplanted the ceremonies and rituals of the actual Haitian religion with more sinister black magic (per The Guardian).

In fact, experts today are keen to stress that the representation of Vodou as being fundamentally evil, malign, or satanic is the antithesis of the misunderstood religion, which through its vivid spiritual cosmology fosters a sense of community and moral guidance as any other religion does. Similarly, whereas gross pop culture depictions of "voodoo" might paint its practitioners as violent — human sacrifice is often a feature of such renderings, but more on that later — peristyles, as Vodou temples are known, are typically welcoming places.

"Vodou tends to be radically unjudgmental," Haitian Vodou scholar Elizabeth McAlister told The Guardian. "The alcoholic, the thief, the homeless, the mentally ill, all of these people are welcomed into a Vodou temple and given respect."

The Origins of Vodou

Vodou is a traditional religion most commonly associated with the modern-day island nation of Haiti. It first emerged on the island in the 16th century, when the island was more commonly known as Hispaniola, as thousands of enslaved West Africans were brought to the island to perform hard labor on the island's sugar cane and coffee plantations. Vodou is often referred to in academia as Haitian Vodou, to specify it apart from other forms, including that practiced in Louisiana. Another version is Vodun, an earlier incarnation that emerged in Africa, elements of which are present in Vodou.

"They were treated as cattle. As animals to be bought and sold; worth nothing more than a cow. Often less," the anthropologist Ira Lowenthal tells The Guardian. "Vodou is the response to that. Vodou says 'no, I'm not a cow. Cows cannot dance, cows do not sing. Cows cannot become God. Not only am I a human being — I'm considerably more human than you. Watch me create divinity in this world you have given me that is so ugly and so hard. Watch me become God in front of your eyes.'"

Rather than evolve in a vacuum, Vodou is derived from pre-existing beliefs brought to Haiti by enslaved people from West Africa. However, it would be a mistake to consider Vodou to be an evolution of purely tribal practices; many who were enslaved also brought with them Christian beliefs that they had developed in their homelands, along with the influence of the French slavers who controlled the island at the time as well as indigenous Caribbean beliefs also fed into how Vodou developed.

The mysterious Lwa

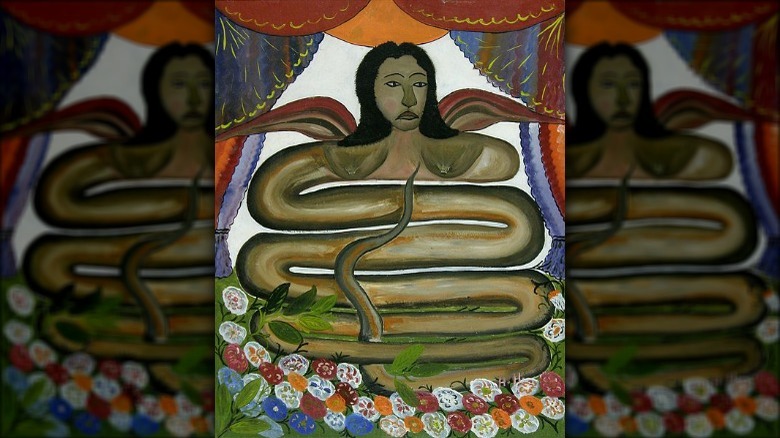

One of the most important beliefs in Vodou is the existence of the Lwa, mysterious spirits that exist as the focal point of much Vodou practice. The Lwa are a large pantheon of different entities that are each associated with specific aspects of Haitian life. Typically grouped into families and attached to such phenomena as fertility and death, the Lwas take a variety of forms, such as that of snakes and other animals, while maintaining some human figures, as represented in Vodou art. According to some senior Vodouisants, there are many thousands of Lwas, some of which are unknown to humans, while individuals or communities might focus their devotion on a certain number of preferred or relevant entities. However, as Vodou is a decentralized religion, the exact number of Lwas that are said to exist varies from community to community.

As powerful and active as the Lwas are in the functioning of the universe and shaping human life and destiny, their pantheon is subservient to another entity, Bondye, the creator god who first made the universe. However, it is commonly believed among practitioners that Bondye is unknowable to human Vodouisants, and is therefore unreachable through prayer or rituals. The Lwas therefore might be considered intermediaries between humans and the divine, with whom Vodouisants grow particularly intimate and affectionate. Alongside Lwa, the ethereal plane of the Vodou world is said to be populated by several other categories of spiritual beings, as well as spirits of the dead.

Ceremonies and reciprocal gestures

Vodouisants generally commune with the Lwa and other forces of Vodou through ritualistic ceremonies which typically seek to involve one particular Lwa, often for a specific purpose. To "sevi Lwa" is literally to "serve the spirits."

For example, Haitian fishermen looking for safe passage and bountiful catches on their fishing trips might make ceremonial offerings to Agwé, the Lwa of the sea. Agwé favorite colors are said to be blue and white, and murkier sea colors, which worshippers conducting ceremonies in Agwé's honor might wear or use to decorate peristyles or gifts to the Lwa. Lwa are said to have favorite gifts, too, and Agwé's are understandably said to be maritime or nautical, such as shells, navigational aids such as telescopes, as well as oars and other sailing equipment. Hot meals as well as drinks of champagne and naval rum are also given as offerings to the Lwa, who in turn is said to bestow his own gifts on those who honor him.

Often, Vodou is associated with ritual sacrifice, which is sometimes rendered as human sacrifice, which is an utter myth. However, animal sacrifice is indeed often a central part of such rituals, with the creature specially blessed and prepared as an offering to the intended Lwa, before becoming the centerpiece of a feast for the community at large.

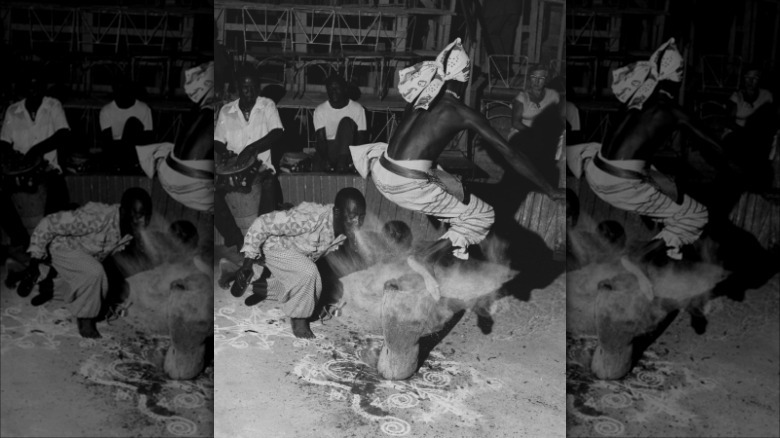

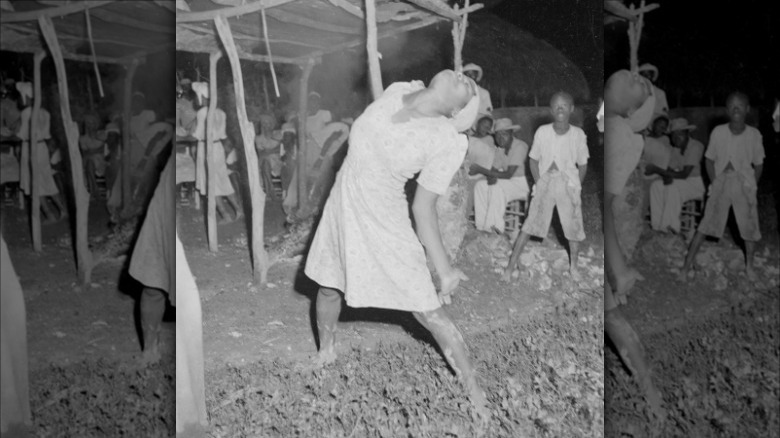

Mounted, not possessed by the Lwa

One of the biggest stereotypes about Vodou when it comes to its representation as "voodoo" in popular culture is that of trancelike possession. Through a Western Christian lens — that which has most vigorously sought to discredit and denigrate Vodou as an African-derived satanism — such practices were reformulated as practitioners being "possessed" by demons under the influence of black magic.

But the spirits intended to be summoned by Vodou rituals aren't demons, but the Lwa, who, rather than "possess" those worshipping them, are said to "mount" them like a steed, a moment which expresses itself in vigorous dancing and other theatrical behavior. Those who are said to be vessels for Agwé, for example, may typically move around the event on a chair, symbolizing the sea Lwa's boat, and shout nautical remarks, while others are encouraged to prevent those who are mounted by Agwé from running into the sea. Similarly, rafts of gifts are often sent out to sea in the Lwa's honor. Such events are joyous, musical, and communal.

And while we're on the subject, zombie resurrection rituals aren't a part of Vodou, either. Rather, zombies exist in Vodou folklore in the same manner golems do in Judaism, or dragons do in Christianity.

Christianity and Vodou

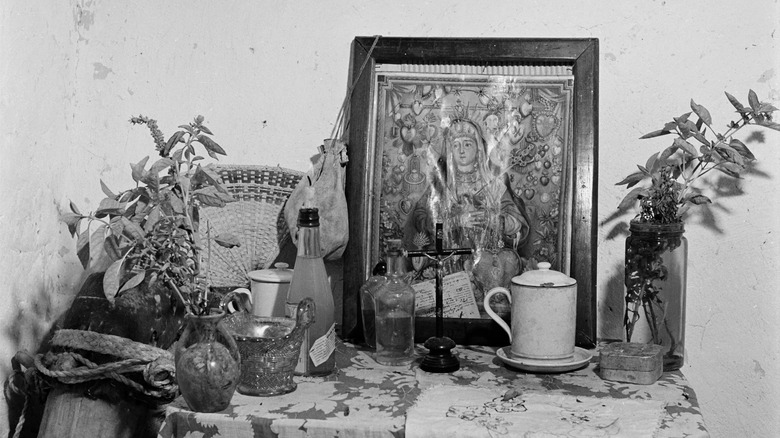

Considering that Vodou's practitioners acknowledge the God of the Christian Bible and have drawn commonalities between the Lwa spirits and various Christian saints, is perhaps tempting to consider Vodou as a denomination of Catholicism. Indeed, the kinds of ceremonies that involve the Lwa as outlined above commonly begin with a Roman Catholic prayer.

However, experts point out that to do so would be a mischaracterization. Rather, Vodou may be considered a syncretism of Christianity and West African Vodun, which nevertheless is its own tradition.

On the enslaved Africans' arrival on Hispaniola, their captors gave them just over a week to convert from whatever belief system they had practiced in Africa to Catholicism, forcing the issue of adapting pre-existing spiritual practices and ideas to fit the standards of their oppressors. Though many sources consider this to be the moment that Vodou was born, its development both precedes and extends beyond this point, with heroes of the Haitian Revolution incorporated into the religion pantheon as Lwa, and the Vodou belief system evolving alongside the Haitian nation itself.