11 Red Flags That The Titan Sub Was Doomed From The Start

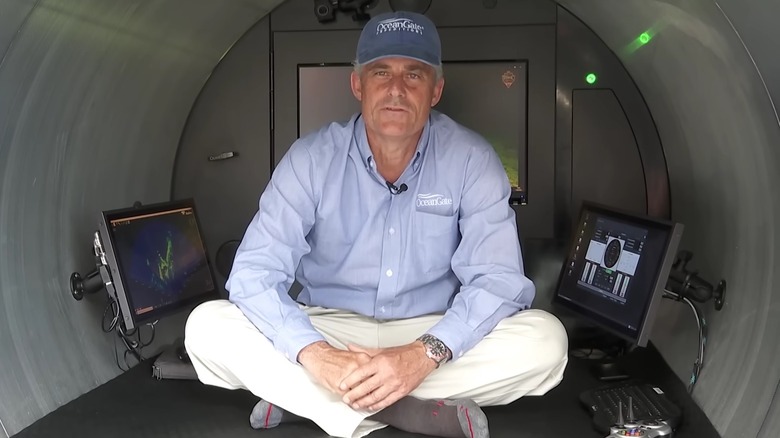

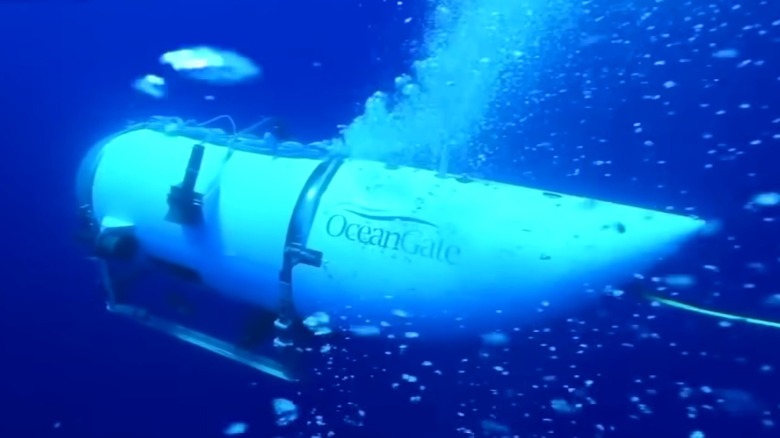

In June 2023, the world was riveted by a drama taking place at sea, near the wreck of the famous, doomed ocean liner RMS Titanic. On the 18th, a private submersible — dubbed the Titan, built by the company OceanGate Expeditions — departed on a five-hour mission to tour the wreck of that vessel with five people aboard: OceanGate CEO Stockton Rush, 61, who was piloting the craft; French explorer and retired naval officer Paul-Henri Nargeolet, 73; British aviator and explorer Hamish Harding, 58; British businessman Shahzada Dawood, 48; and his son Suleman, 19. Just hours after beginning its descent, the craft lost contact with its companion surface vessel, and it failed to resurface at its scheduled time. A massive search and rescue operation followed. On June 22, the United States Coast Guard confirmed the remains of the Titan had been found near the wreck of the Titanic. The sub had suffered a catastrophic implosion, killing all aboard near-instantly.

The tragedy may spell the end for OceanGate, which suspended all operations in its wake. Founded in 2009, Rush claimed it had been on the cutting edge of deep-sea exploration. The Titan was its second submersible, and first to be designed and built from scratch; in 90 attempts, all within the last few years, the vessel had reached the Titanic a total of 13 times. Its fateful final voyage may have shocked the world — but the marine exploration community was not exactly taken by surprise, having seen the warning signs for years.

A distant early warning

Stockton Rush was a man enamored of the Titanic wreck; he spoke about it in reverent terms, and his determination to make the wreck accessible to tourists was matched only by his passion for innovation. The Titan, like its predecessor the Cyclops 1, was an experimental craft; it had not been evaluated or classed by any regulatory body, and some of the materials used in its construction were unconventional, to say the least. In particular, the craft had a hull constructed from carbon fiber — a material which has many applications in aerospace, but which has not been extensively tested or graded for use in submersibles.

In 2015, while Rush was designing the Titan, he consulted with submersible company DOER Marine Operations, which had recently completed a research project known as Project Deep Search. Its president, Liz Taylor, spoke with ABC News in the aftermath of the Titan's implosion, and what she had to say was astonishing. "We all told him, someone is going to be killed in this thing and you've got to not do it," she said. "The carbon fiber, it's been shown to not be very happy when it's being immersed ... it's not the right material." Taylor explained that the Marine Technology Society echoed her concerns in a 2018 letter to Rush, but the CEO failed to heed their advice. "[He was] confident in [his] engineering and kind of just went down a path of really kind of thumbing the nose of the classing agencies," she said. After repeated dives, the hull was even rebuilt in 2020 due to fatigue — and yet, the expeditions to the Titanic continued.

Some highly unconventional design choices

Its carbon fiber hull was far from the only questionable aspect of Titan's design, many details of which emerged after the craft went missing. A November 2022 report by CBS Sunday Morning was immediately cited by a slew of media outlets, revealing some eye-popping details: correspondent David Pogue, who had signed on to take the journey to the Titanic, stated outright that he was nervous about how many components of the sub seemed "improvised." For the cameras, Rush pointed out parts of the vessel that he had purchased from RV outlet Camper World, touted the craft's "off-the-shelf" electronics, and showed Lodge the shocking means by which the Titan was piloted: with a third-party Sony Playstation controller, which interfaced with the steering and propulsion system not by hard wiring, but by Bluetooth.

In the piece's interview segment, Pogue good-naturedly pointed out to Rush, "It seems like this submersible has some elements of MacGyver-ing jerry-riggedness." Rush, of course, took issue with that description, characterizing the craft's more unconventional design elements as essentially being irrelevant to its capacity for keeping its occupants alive. "Everything else can fail," he said. "Your thrusters can go, your lights can go, you're still gonna be safe."

Inaccurate claims by Rush

During that conversation with CBS Sunday Morning, Rush got relatively explicit when talking about the level of engineering that had gone into the Titan's design. Following up on Pogue's assertion that the craft seemed, well, kind of slapped together, Rush said, "There's certain things that you want to be buttoned down. So, the pressure vessel ... is where we worked with Boeing and NASA and the University of Washington." This was not the first time that Rush had invoked those institutions in touting the safety of his design; in fact, a (now-defunct) page on the company's website asserted that the Titan had been designed and engineered "in collaboration" with those very entities. This, however, was not accurate.

As the search for the Titan was ongoing, all three of those institutions issued public statements distancing themselves from the design and engineering aspects of OceanGate's endeavors. In a brief statement to Business Insider, a Boeing spokesperson said simply, "Boeing was not a partner on the Titan and did not design or build it." The University of Washington issued a more detailed statement to CNN, clarifying that its brief research partnership with OceanGate had resulted in the steel-hulled Cyclops 1, and that "the Laboratory was not involved in the design, engineering or testing of the TITAN submersible." Finally, NASA provided a statement to Business Insider reading in part, "[NASA] consulted on materials and manufacturing processes for the submersible. NASA did not conduct testing and manufacturing via its workforce or facilities, which were done elsewhere by OceanGate."

An OceanGate employee took the company to task over safety

As the Titan was nearing its maiden voyage, one of OceanGate's employees issued a report that, by any measure, should have been a major roadblock to its deployment. This wasn't just any employee: David Lochridge carried the title of Director of Marine Operations and was the submersible's chief pilot, and in his report, he took Rush to task for failing to properly test the carbon fiber hull. He pointed out that a scale model had displayed "prevalent flaws," and that the carbon fiber of the actual hull was visibly stressed in a way that could easily lead to catastrophic failure under the enormous pressures of the deep sea. He further opined that the sub's acoustic monitoring system for detecting impending failure, developed in-house by OceanGate, was woefully insufficient, and would not provide enough advance warning to make a difference.

Alarmingly, Lochridge opened his report by stating that its purpose was to establish a written record of his concerns, as "Verbal communication of the key items I have addressed in my attached document have been dismissed on several occasions." Rush's response to the report was swift: he fired Lochridge and filed a lawsuit against him claiming that he had violated his non-disclosure agreement by raising his concerns with the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA). Lochridge promptly filed a countersuit, claiming that he had been wrongfully terminated for raising completely valid concerns — and while the dueling suits were eventually settled, those concerns were never properly addressed.

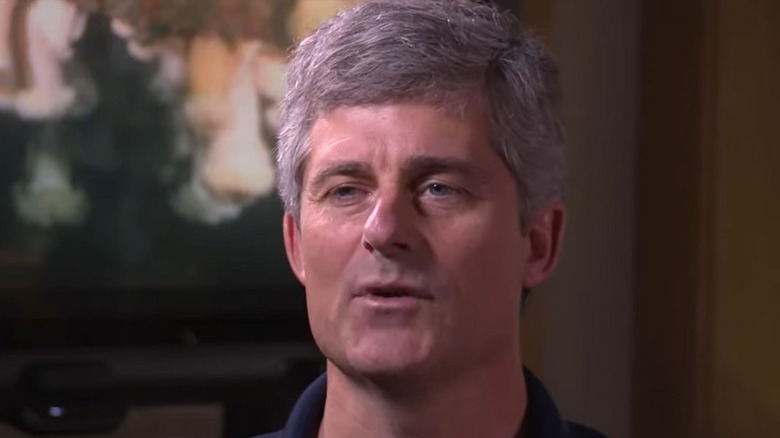

Another former employee expressed concerns in dramatic fashion

The assertions made by David Lochridge with respect to the Titan's safety issues were downright diplomatic compared to those made by his former co-worker, Rob McCallum. McCallum had previously owned a company that conducted Titanic expeditions using two Soviet-manufactured subs, and he was involved with helping plan the Titan's expeditions — right up until the point that Stockton Rush made the final decision not to have the craft evaluated by classing agencies, whereupon he departed the company, according to The New Yorker. In 2018, after hearing of Lochridge's departure, McCallum shot him an email — and what Lochridge had to say floored him.

"That sub is not safe to dive," Lochridge wrote. "It's a lemon." In further correspondence a couple weeks later, Lochridge wrote, "There's no way on earth you could have paid me to dive the thing ... I'm so worried [Rush] kills himself and others in the quest to boost his ego." Alarmed, McCallum emailed Rush, stating his concerns in no uncertain terms. "You are wanting to use a prototype un-classed technology in a very hostile place," he wrote. "You are potentially putting an entire industry at risk." The response from Rush was shocking and, in light of the Titan's eventual fate, tragic in its audacity: "We have heard the baseless cries of 'you are going to kill someone' way too often," he wrote. "I take this as a serious personal insult." Strangely, Rush then invited McCallum to come back to work for him — and threatened him with a lawsuit when he refused, ending their correspondence.

Rush tried to make his accountant the Titan's head pilot

If the claims of another unnamed former OceanGate employee are accurate, the unwillingness of Stockton Rush to listen to anybody who had anything to say about the Titan's potential to catastrophically fail was symptomatic of a brazenly cavalier attitude toward all aspects of the project. In The New Yorker's piece, the former employee — who was OceanGate's director of finance and administration — revealed that after Lochridge was terminated, she was approached by Rush to take over as the vessel's lead pilot, a position for which she was wholly unqualified.

"It freaked me out that he would want me to be head pilot, since my background is in accounting," she said. She added that at this point, OceanGate was also largely staffed with engineers who were likewise unqualified — some just teenagers making 15 dollars per hour. Alarmed by the absence of anyone willing to challenge Rush, she began searching for another job — and as soon as she got an offer, she quit OceanGate. "I could not work for Stockton," she said. "I did not trust him."

Courting danger by cutting corners

There are few more hostile environments known to man than the depths of the ocean, and in building vessels capable of exploring those depths, there are no corners to be cut. That, however, didn't seem to stop Stockton Rush from cutting a few anyway — notably in the design of the Titan's electronics, which as previously noted were not exactly assembled from cutting-edge technology. In fact, those systems were designed not by experienced engineers, but by a team of interns composed of recent graduates of the University of Washington's School of Engineering. In a 2018 piece featured in the school's newspaper, the WSU Insider, team member Mark Walsh gushed over his involvement: "The whole electrical system — that was our design, we implemented it and it works," he said. "We are on the precipice of making history and all of our systems are going down to the Titanic. It is an awesome feeling!"

Unbelievably, though, this was far from the most significant corner to be cut. In a blog post on the website Travel Weekly while the search for the Titan was ongoing, editor-in-chief Arnie Weissman revealed that in advance of his participation in a planned 2023 Titanic expedition (one which was ultimately canceled due to inclement weather), Rush admitted to him that the carbon fiber used in the Titan's hull was acquired at from Boeing at a steep discount — because it was past its shelf life for use in aircraft. "It is a conversation I have thought about a great deal over the past week," he wrote.

Rush did everything in his power to avoid regulation and liability

It should be noted that private companies that build marine vessels are in no way exempt from regulatory oversight. In order to avoid such oversight — and to succeed in repeatedly transporting paying customers to dangerous depths in an unclassed, experimental submersible that had not been evaluated by any qualified agency — Stockton Rush had to go to some pretty extreme lengths, up to and including taking precautionary measures to ensure that OceanGate would not face serious repercussions even its clients were to face serious injury or death.

Those measures, as described for The New Yorker by an anonymous former OceanGate official, were myriad. Although the Titan was constructed in the United States, it was registered in the Bahamas, and operated only in international waters, outside the jurisdiction of U.S. law. OceanGate's clients did not purchase its services — they made contributions, and they were not classified as passengers. The reason for this is simple, according to Rob McCallum: even under U.S. law, it virtually absolved OceanGate of liability even if the worst were to happen. "Under U.S. regulations, you can kill crew," McCallum stated bluntly. "You do get in a little bit of trouble, in the eyes of the law. But, if you kill a passenger, you're in big trouble. And so everyone was classified as a 'mission specialist.'"

Several potential OceanGate customers bailed on the trip

One blatant sign of trouble that might have compelled any of the doomed "mission specialists" of the Titan's final voyage to bail on the trip, had they been aware of it: the tendency of a goodly number of the company's potential clients to do just that. In the years leading up to the disaster, many whom had either signed up for the expedition or had been courted to do so canceled or outright refused, with virtually all of them citing safety concerns as the primary reason — and in the wake of the Titan's disappearance, they began to come forward.

Speaking with CNN, Chris Brown — a friend of Hamish Harding — explained why he gave up his seat on an expedition after signing on in 2018. "I ... had some reservations about the way it was being constructed," he said. "When they weren't even intending to get certification by calling it an experiment, that's when I thought there's just too many red flags here, so I pulled out." Former U.S. Marine and maritime project consultant Robert Mester declined a trip on the Cyclops 1 after casting a wary eye at its off-the-shelf navigation and propulsion instruments, and similarly turned down a seat on the Titan, citing the untested nature of its carbon fiber hull, according to The Daily Beast. And Las Vegas business mogul Jay Bloom, despite being offered a steep discount on the standard $250,000 admission fee, also begged off. "The more we learned, the more concerned we became," he told BBC News. "[Stockton Rush] completely disregarded his deviation from the industry norms." He then added, a touch hyperbolically, "[He's a] lone wolf without resources, who put things together with duct tape and WD40."

An earlier dive almost ended in disaster

The Titan's fateful final mission was not the first time that something had nearly gone terribly wrong during one of its Titanic missions. In 2022, as detailed by The New Yorker, a BBC documentary crew was present for one of those missions, which saw OceanGate director of logistics Scott Griffith piloting the craft with four others aboard, while Rush stayed behind on the surface vessel. A diver accompanying the sub for the initial stage of its descent noted that something seemed a bit amiss with one of its thrusters — but Rush allowed the dive to continue. Once it touched down on the ocean floor, it became quickly apparent that the diver had been correct — the thruster had been installed improperly, and sitting in the middle of the Titanic's highly dangerous debris field, all Griffith could do was spin in circles.

From the surface vessel, Rush sent down a solution: to remap the Playstation controller, an endeavor which required one of the passengers to download an image of the device from the internet. The gambit worked, and somehow, Griffith managed to pilot the craft over to the remains of the Titanic with his only means of navigation completely reconfigured from how it had been during his training. Amazingly, the mission was completed without any more serious difficulty, but of course, in the end, it wasn't the shoddy electronics that sealed the fate of the Titan and its passengers, but the crushing pressure of the ocean.

Rush constantly talked about breaking rules and disregarding safety measures

Of all the glaring red flags presented by Stockton Rush and his company in advance of the Titan tragedy, perhaps the most obvious was Rush's own oft-repeated insistence that breaking the rules is a good thing, a sentiment that carries the implicit notion that safety is secondary to innovation. At a GeekWire summit in 2022, he summed up that philosophy succinctly, saying, "If you're not breaking things, you're not innovating. If you're operating within a known environment, as most submersible manufacturers do, they don't break things. To me, the more stuff you've broken, the more innovative you've been." In a widely-viewed interview with Alan Estrada for his YouTube Channel, he clearly stated his disdain for pesky regulations: "There's a rule you don't [use carbon fiber in submersibles]," he said. "Well, I did."

Perhaps Rush's most egregious comments came during a November 2022 interview with David Pogue on the Unsung Science podcast. "You know, at some point, safety is just pure waste," he said. "I mean, if you just want to be safe, don't get out of bed, don't get in your car, don't do anything ... I think I can do this just as safely while breaking the rules." Rush was obviously proven quite wrong, and as pointed out by Rob McCallum to The New Yorker, it really depends upon the type of rules one is talking about. "You can't cut corners in the deep," he said. "It's not about being a disruptor. It's about the laws of physics."

[Featured image by OceanGate via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled | CC BY-SA 3.0]