These Popular Board Games' Surprising Histories

When you hear your grandparents talk about playing Monopoly, chess, or the Game of Life when they were kids, it's easy to wonder if all those classic board games have existed since cavemen were around, using little rocks as pieces and a painted stone slab instead of a board. In reality, though, the origins of most board games aren't that mysterious. Some of them do have surprisingly ancient beginnings, but others are as contemporary as the home television set. What's really bizarre is the back story behind why many popular board games were created. While some started their life as moralizing educational tools, others were designed as forms of escapism from the biggest historical crises of the 20th century.

If you've ever wondered how and why people starting bankrupting each other for fun, knocking over towers of little wooden blocks, or trading cards inscribed with profanity, here's the inside scoop.

Polite society was offended by Twister

Back in 1965, a dude named Reyn Guyner was working on a lame, boring, polka-dotted ad campaign for kid's shoe polish, when he stumbled upon the way more fun idea of using a giant polka-dotted mat as a game "board" and turning real human beings into game pieces. While this sounds like something an evil wizard might come up with, Mental Floss says Guyner was able to convince two professional game designers to partner with him. The game they created was originally called "King's Footsie" (uncomfortable), then "Pretzel" (not bad), and was finally dubbed "Twister" after Milton Bradley picked it up.

Now, here's the thing about Twister: While most board games ask you to sit upright like a civilized human being, Twister knows that, deep down, all you actually want to do is get tangled up with your fellow hairless primates and collapse into a heaping, laughing, sweaty pile on the floor. All this touchy-feely stuff made a bunch of repressed execs uncomfortable. The Sears catalog didn't want to run ads, and one competitor even called Twister "sex in a box." Great tag line, but the game's sales were tanking until a clever PR firm swooped in at the last minute and submitted Twister to The Tonight Show. Once audiences saw Johnny Carson and Eva Gabor flopping about on live TV, everyone rushed to the stores.

The original Monopoly was all about bashing capitalism

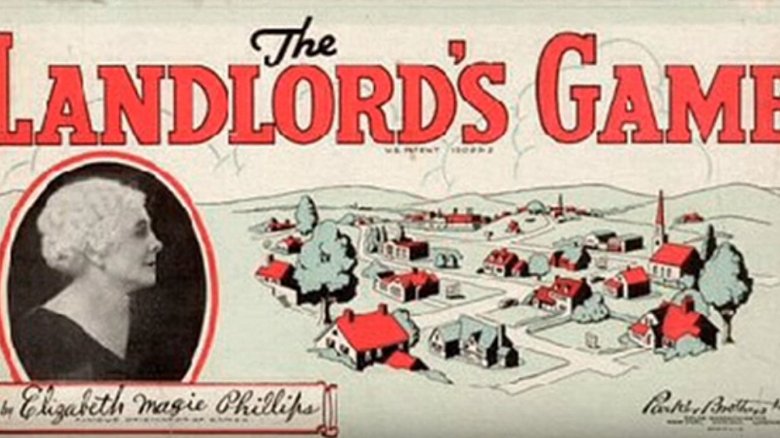

Today's Monopoly is often presented as some sort of glorified bourgeois fever dream which usually lasts for 10+ hours, but the original concept for the game was something even Star Trek creator Gene Roddenberry would've cheered on. Though Monopoly's invention is often attributed to Charles Darrow in the 1930s, the Smithsonian points out that the true credit goes to a feminist artist named Lizzie Magie, who patented "The Landlord's Game" in 1904. Magie's intentions behind The Landlord's Game were highly political: She wanted to teach regular folks that rich corporate autocrats were abusing the working class, keeping them in poverty to accrue massive sums of wealth for themselves.

Homemade versions of Magie's educational tool in the evils of income inequality became popular among various intellectual circles until the Great Depression, where that aforementioned Charles Darrow guy ripped off the concept, renamed it Monopoly, and sold it to Parker Brothers. Surprisingly, Lizzie Magie responded merely by selling off her rights to The Landlord's Game, hoping that if her concepts reached the masses, they could do some good in the world. In the end, Monopoly made millions of dollars and became the ultimate symbol of capitalist greed, while Darrow got all the credit for the game's innovative design. It wasn't until 40 years after Magie's death that her true role in the game's creation was recognized, according to Biography.

Candy Land was made for kids with polio

One of the greatest medical triumphs of the 20th century was Dr. Jonas Salk's invention of the polio vaccine in 1953, according to History. Before that, polio was infecting, paralyzing, and killing thousands of individuals, often children. These victims included a schoolteacher named Eleanor Abbott, and the American Journal of Play says she soon found herself placed in a San Diego polio ward, unable to go outside and surrounded by polio-stricken children.

Surrounded by sickness and despair, Abbott sought to help these children by creating a bright, colorful, happy form of escapism, with simple rules and easy victories. This became Candy Land, a game Abbott took with her out of the ward and sold to Milton Bradley in 1949, where it's since become known as the first board game of many children, according to the National Museum of Play. These days, Candy Land's connections to polio aren't as visible as they used to be: For example, while early game boards depicted a young boy wearing a leg brace, later editions have avoided such references. However, Eleanor Abbott herself never forgot the game's roots. Though she lived a quiet life, it seems she received many royalties over the years, which she mostly donated to paralyzed children.

Those chutes are supposed to be snakes

If you grew up in the United States, everything you've ever assumed about Chutes and Ladders, that seemingly simple game that turns the board into a two-dimensional jungle gym, is probably false. For one, those swirly slides were originally venomous snakes. Two, the design is over 2,000 years old. Three, it's not supposed to be a "game" so much as an illustration of complex philosophical principles. Feeling dizzy, yet?

As the Times of India explains, the concept goes back to India in the second century B.C. Though the board resembled the one you know today, the ladders were supposed to represent good, virtuous deeds, while the serpents stood for the slippery slopes of evil. Basically, if you do good things, you'll climb into higher states of consciousness, and if you act like a petty jerk, you'll go sliding back down on the back of a snake, but chance is still the ultimate determiner.

A harsh lesson? Sure, but effective. Winning the game meant achieving moksha, or deliverance from the endless cycle of rebirth. Unfortunately, a lot of this spiritual depth got lost when Europe adapted the game, and the American version takes all the bite out of the snakes by turning them into chutes. Nonetheless, the symbolism is still there, though it's subtle.

World War II ruined English house parties, and Clue was the cure

Back in the 1930s, a young Englishman named Anthony Pratt was a crime aficionado, with a talent for the piano and a love for party games, according to the Independent. Then World War II broke out, and all these happy things came grinding to a halt. Frequent air-raid blackouts meant the streetlights went dark, people stayed in their homes, and the English social scene went kaput.

Pratt knew he had to do something to save his beloved dinner parties from oblivion, so he invented a board game called "Murder!" where a collection of quirky characters with names like Professor Plum, Reverend Green, and Colonel Yellow (not yet Mustard) explored a country home and tried to solve a deadly mystery. He sold the game to Waddington's in 1945, but post-war material shortages delayed it for four years, at which point it was finally released as Cluedo in England, and Clue in the United States. Sadly, sales weren't so hot. Pratt gave up, and History says in 1953 he sold the game's foreign rights for £5,000, figuring he'd be better off cashing in early. In a tragic twist of fate, the game's overseas sales took off after that, leaving Pratt broke while Clue went on to become a worldwide phenomenon.

The Yahtzee! legend involves ... well, yachts

What does a funky word like "Yahtzee" mean, anyway? Actually, not much. If you believe the legend, though, it might have something to do with yachts.

According to Hasbro, Yahtzee was the creation of a wealthy, anonymous Canadian couple who, like many wealthy couples, enjoyed going out on their yacht. When they'd invite friends along, they played the so-called "yacht game," and these friends started demanding their own copies of the game. The couple reportedly decided to approach Edwin S. Lowe, the guy who made a bundle on a little game called Bingo, and requested gift copies. Instead, Lowe was so enthused about the yacht game that he bought it outright, renamed it Yahtzee, and mass-marketed it. Needless to say, this whole "anonymous couple" legend sounds a bit fishy, and not just because of the whole boat aspect. It's awfully convenient that the couple is unnamed, and nobody has ever come forward to back up the tall tale. Nonetheless, for now, this is the origin story Yahtzee's owners are selling, so it'll have to do.

Honest Abe indirectly created the Game of Life

Back in 1860, the United States was in a rough place, with a dramatic presidential election splitting the country in two. In the midst of this chaos, though, one young chap was happy as a clam. His name was Milton Bradley, according to The New Yorker, and he was making big bucks on a special lithograph of Abraham Lincoln, that controversial yankee candidate who was angering the southern states with his abolitionist views. Then, Lincoln grew a beard. Good for Lincoln — it's the most iconic facial hair ever — but not good for Bradley, whose lithograph instantly became worthless.

Desperate to turn his fortunes back around, Bradley whipped up a board game called the Checkered Game of Life, hit the road for New York and sold it as a tool to teach children how to lead "exemplary lives." Moralizing propaganda, basically. If you think today's Game of Life is socially, politically, and morally puritanical, well, try playing Bradley's original (second edition pictured above), which included dark possibilities like suicide and disgrace if you didn't live a "perfect" life. Yikes! The reason the original game didn't even use dice, according to the Roy Rosenzweig Center, was to avoid any association with awful, immoral gambling. Bradley sold 4,000 copies in his first year and struck up a pretty lucrative business.

Hasbro didn't like the name 'Jenga'

Leslie Scott spent her childhood moving between various African countries, and while she was growing up, she and her siblings made a fun game out of stacking castoff chunks of Ghanaian hardwood, each piece possessing a different look, weight, and texture. These differences, according to Kotaku, were what made the game unique. When Leslie moved to England in her 20s, she brought the hardwood blocks with her, and they became a hit whenever she attended social functions. Like any young and ambitious inventor, Scott decided to shoot for the stars, according to The Guardian, and she had 100 sets of blocks made, carefully replicating those all-important imperfections in the wood. By 1983, she started presenting them at toy conventions as Jenga, a Swahili word she identified as meaning "to build." Sales were slow, but after Jenga was picked up by Irwin Toys, and then Hasbro, the game shot through the roof.

The one problem? Both companies wanted her to ditch the name, thinking no one would understand it. Thankfully, Scott stood her ground, and Jenga has been Jenga ever since.

Cards Against Humanity got its start in high school parties

Hey, you never know: If you play your cards right, that silly game you made up with your childhood buddies might become a smashing success. Just ask Max Temkin and his squad of seven lifelong friends, who according to Kickstarter handled the perils of awkward teenage socialization by playing structured games. In 2008, the crew was scheduled to throw a big New Year's party, and none of their old games fit the bill. So they got their composition books, drafted up hundreds of disturbing, sinister, and uncomfortable prompts, then typed them up in Microsoft Word and printed cards. Once December 31 rolled around, a game they called "Cardenfreude" was born.

The name didn't stick, obviously. But the concept did, and by 2009, the friends put up a website for their creation. In late 2010, Cards Against Humanity had morphed into a Kickstarter campaign, which raised over $15,000, turning the world's most horrible game for horrible people into an instant classic. These days, the old crew is basking in their success, using their money to fund purchases like buying Hawaii 2, an uninhabited island off the coast of Maine.

Chess is younger than you think

Everyone thinks of chess as a board game older than time itself. If Cain and Abel didn't invent it during one of their infamous sibling squabbles, it probably came from ancient Egypt or perhaps started during a heated argument between Plato and Aristotle. Right?

Wrong. Strangely enough, chess ain't that old. According to the Joukowsky Institute for Archaeology, the world's most intense game has only been around for about 1,500 years. The original form of chess was an Indian game called Chatrang, first played around the fifth century A.D., which featured animal warrior pieces trying to take down the opponent's king. If you like today's version of chess, though, the Independent points out that you can thank the Persians. Once Persian society got hold of chess, they embraced it. To the Persians, chess wasn't a mere "game," but an important occupation, an educational tool, and the easiest way to figure out who your most intelligent planners, leaders, and/or advisers were. This was the golden age of chess, and while the anthropomorphic game pieces everyone knows today didn't come about until the game spread to medieval Europe, there's never been another era where chess was taken so seriously by everyone involved.