What Is Sikhism And What Do Followers Believe?

Depending on where you live, saying the words "major world religions" will likely bring obvious contenders to mind, particularly Christianity and Islam. Those religions stand at the forefront because of numbers and global saturation. World Population Review data from 2020 puts Christianity at almost 2.4 billion followers worldwide, Islam and about 1.9 billion, Hinduism at 1.16 billion, and Buddhism at 507 million. After that, numbers drop off quickly. Out of that list, Hinduism and Buddhism stem from the Indian subcontinent. But folks in Western countries might not know that there's a third major world religion — and fifth most practiced, globally — that also comes from India: Sikhism.

The London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE) puts Sikhism at 26 million practitioners worldwide, most of whom live in India in Sikhism's birthplace in the state of Punjab. Sikhism is a young faith compared to its peers, coming of age from the birth of founder Guru Nanak in 1469 C.E. till the death of its final guru, Guru Gobind Singh, in 1708 C.E. Outside of India, Statista shows us that most Sikhs live in the English-speaking world, especially the U.K., U.S., Canada, and Australia. Yet for such a widespread religion, many people remain ignorant about even the basics of Sikhism. On top of that, Sikhs have faced a lot of prejudice wherever they've gone, as sites like NBC News or SikhNet describe. But no matter what, Sikhism remains a vibrant, kind-hearted, common-sense faith that focuses on humility and helping others.

Hindu meets Muslim meets Buddhist in Punjab, India

Sikhism is the world's youngest major religion, clocking in at about 550 years old. As such, it comes equipped with the benefit of hindsight of earlier religious beliefs, particularly Hinduism, Islam, and Buddhism, and also takes inspiration from these traditions no matter that Sikhism is very much its own faith. This likely wasn't a conscious choice on the part of Sikhism's founder, Guru Nanak, but a natural result of geography.

Guru Nanak was born in 1469 C.E. in modern-day Punjab, India, at the time ruled by Muslim Mughal leaders. As the BBC explains, the Mughals overhauled India's government, laws, language, art, and fused native Hindu beliefs with Arabic-influenced, Islamic values. That means Guru Nanak grew up in a Hindu-majority, Muslim-led nation that was also influenced by Buddhism, which itself had diverged from Hinduism about 1,000 years prior. This eclecticism underscores Sikhism's beliefs. Sikhism is monotheistic (like Islam), has a lineage of revered gurus (like Hinduism), and denounces ego and attachment to the material world of Maya, aka illusion (like Buddhism), as Discover Guru Nanak overviews.

As the British Library says, Guru Nanak grew up in the Khatri caste — an accountant caste — and worked as a shopkeeper for a Muslim government official. In this perfect position of societal observation, he had a revelation at age 30 about the oneness of all people. He gave away his possessions, traveled while teaching, gathered followers, and eventually settled in Kartarpur: "Creator Town."

From teacher to learner

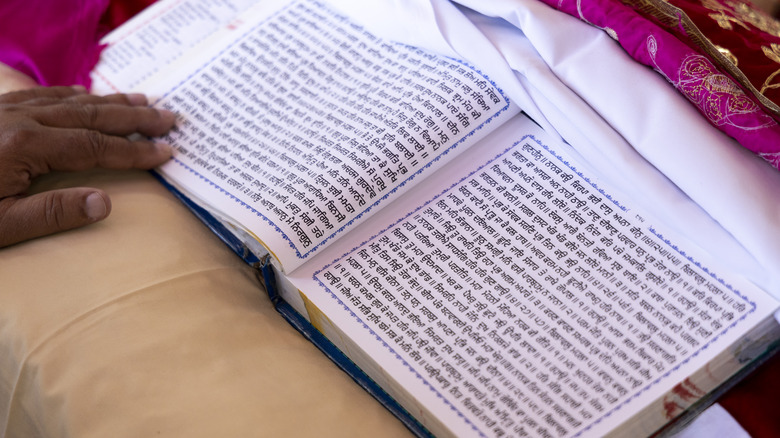

As The Sikh Coalition explains, Guru Nanak was the first of a line of successors that honed Sikhism's beliefs and practices over time. The 10th and final guru, Guru Gobind Singh, died in 1708 C.E. His death more or less sealed Sikhism's foundational years, which ended with the codification of Sikh beliefs into Sikhism's single, sovereign, holy text, the Guru Granth Sahib. The Guru Granth Sahib and its collective words, tales, and lessons are regarded as a kind of eternal, bodiless guru presiding over and guiding Sikhs in the present. For the curious, Sonapreet has a family tree of the entire lineage of Sikh gurus.

The Guru Granth Sahib, like many other holy texts, is written in poetic form. Aside from just being a practical way to compose and memorize stories, poetic verse goes back to Guru Nanak himself. The British Library says that he composed verses with his Muslim traveling companion, Mardana, who played the rabab, a three-stringed instrument modernly associated with the regional swath of Punjab through Pakistan, Afghanistan, and out to Iran. All of the gurus' poems — shabads, by the Sikh term — teach about common principles like integrity, generosity, and a lack of vanity. They're dense in imagery, and that imagery is meant to reveal greater universal truths. All of this information passes from Guru (teacher) to Sikh (learner). Sikh Coalition and SikhNet explain that all Sikhs together are considered another, collective, perpetually living guru: the Guru Khalsa Panth.

The selfless service of seva

When hearing about Sikhism — especially that Sikhism is monotheistic — folks in Western, Judeo-Christian countries might want to immediately cling to tiny fragments of doctrine, the specifics of Sikhism's godhead, and all the sorts of textual complications that have accreted in Western religions over time. When dealing with Sikhism, it's best to forget all that.

What sets Sikhism apart from its peers is an absolute, grounded practical-mindedness about humanity and bettering the world. Forget all the talk, debate, discussion, division, rhetoric, niggling points of theology, and focus on one thing: seva. As Time, the BBC, India Today, and more describe, seva (or sewa) is the Sikh term denoting Sikhism in practice. It involves stowing words and getting to work acting out of love, self-sacrifice, and justice. Seva, perfectly reflecting the world of Guru Nanak and our own, centers on the unity of all people and, per India Today, "is the very antithesis of hegemony of any kind."

To illustrate: have a look at the Sikh Coalition's Seva page, which lists outreach programs headed by sevadaars — Sikhs practicing seva. Many programs revolve around feeding the hungry. When COVID-19 gripped the world, Sikhs didn't whine — they hand-delivered food to those in need, per the BBC and CNN. When Cyclone Gabrielle hit New Zealand, Sikhs delivered 1,000 meals per day, per the New Zealand Herald. When floods battered British Columbia, Sikhs did the same, per CTV News. On and on it goes.

[Featured image by Jayvenroo via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled | CC BY-SA 3.0]

Holy days and dress

Like other faiths, Sikhism has festivals, holy sites, guidelines for dress and appearance, etc. The most important annual Sikh event is undoubtedly Vaisakhi, the first day of the month of Vaisakhi in the Sikh calendar, as SikhNet explains. For our current, global, shared calendar, that's about April 13 or 14, dates that point to Vaisakhi's roots as a kind of spring harvest festival. The 10th Sikh guru, the aforementioned Guru Gobind Singh, instituted Vaisakhi in 1699 when he asked all Sikhs to congregate in Anandpur, Punjab. That's when he dubbed five initiates the first Guru Khalsa Panth, the collective, perpetually living guru.

Perhaps in an attempt to formalize Sikhism or create a unified Sikh identity, Guru Gobind Singh also asked Sikhs to adopt the five K's: "Kes (uncut hair), Kangha (a small comb), Karra (an iron bracelet), Kachera (a white undergarment), and Kirpan (a small curved sword of any size, shape or metal)." Sikhs were to be "Saint-Soldiers," ready to help others as needed. His first Khalsa initiates also wore orange, a tradition that carries on in Vaisakhi to this day. As for the ever-recognizable and much-misunderstood Sikh turban, The Guardian explains that turbans predate Vaisakhi and go all the way back to Sikhism's founder Guru Nanak. He wore a turban as a sign of respect in the presence of the divine. On Mashup Americans Sikh Rupinder Singh describes the importance of turbans, and how they must be worn outside of the home.

Sikhs around the globe

At present, pockets of Sikh communities have sprouted on all continents. As an article in GeoJournal on JSTOR explains, the Sikh diaspora happened largely in response to British rule over India, aka the British Raj. This lasted from 1858 to 1947 when the modern nations of India and Pakistan were formed. The London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE) says in 2023 that there are about 26 million Sikh globally, with 23 million living in India. Most of those live in the place of Sikhism's birth, Punjab. Statista, recounting figures from 2020, shows that the majority of Sikhs living outside of India live in the Anglophone world: the United Kingdom, Canada, the United States, and Australia, in that order.

If the soul of Sikhism still lives in Punjab, so does its holiest of places: the Golden Temple in the city of Amritsar. The Golden Temple is not only an important Sikh pilgrimage site, as the BBC explains, but a testament to Sikhism in practice. The Golden Temple hosts weddings, is open to the local community 24/7, and is tended by a legion of volunteers who clean it and provide food to the needy. Anyone, from anywhere, at any time, regardless of class, caste, religion, ethnicity, gender — whatever — is free to go to one of the Golden Temple's food halls and eat a free meal of lentils, chickpeas, chapatis (flatbread), and yogurt. Such selfless service provides a shining model for the rest of us.