The Controversial Side Of Body Worlds

For many, anatomy is a subject that's bound to generate discomfort. The sight of the human body broken down into its disparate parts, even in a bloodless illustration, is enough to send one's brain into a tailspin. Of course, not everyone gets the heebie-jeebies when they crack open an anatomy textbook — otherwise, we wouldn't have anatomists, surgeons, or any other sort of doctor. But even medical professionals might find themselves pausing at the entrance to the exhibit known as "Body Worlds."

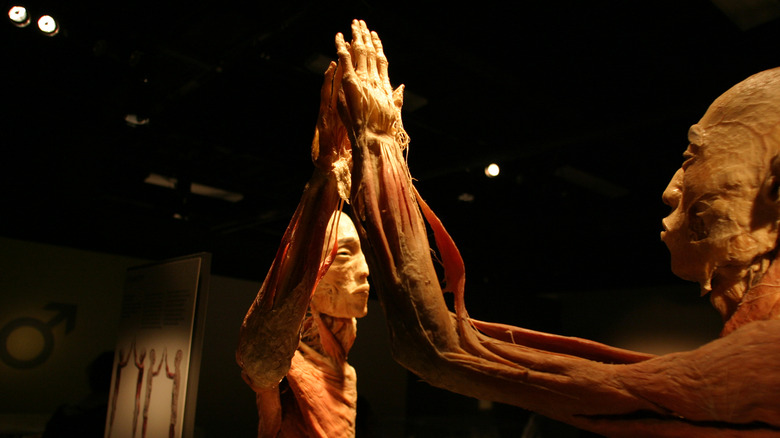

"Body Worlds" is a series of exhibits that first opened in 1995 under the aegis of German anatomist Dr. Gunther von Hagens. Inside are displays of human remains that have been carefully posed and dissected to dramatic effect. These exhibits are made possible by plastination, a technique pioneered by von Hagens in which fats and water in a body are replaced by polymers, allowing the corpse to be preserved and examined for a very long time. That's useful for medical students, but von Hagens has taken it a few steps further by arranging donated remains in striking tableaux in his workshop, putting them in traveling exhibits, and charging admission.

Von Hagens' stated goal is to increase public engagement with science and medicine, especially when it comes to preventative care. Yet, not everyone has welcomed the latest iteration of "Body Worlds" when it rolls into their town. From religious qualms to questions about just whose bodies are on display, "Body Worlds" has experienced more than its fair share of controversy.

Gunther von Hagens has generated controversy on his own

Gunther von Hagens is no stranger to controversy, even when he's operated outside of his sometimes infamous exhibit's purview. In 1977, at Germany's University of Heidelberg, von Hagens first began experimenting with the technique of preserving tissue via plastination. For a while, it remained a technique that was largely used just by anatomists to preserve specimens for study. Over time, of course, that changed dramatically. In the interim, von Hagens also developed an eye-catching fashion sense, wearing a now-characteristic brimmed black hat whenever in public. It's a nod to the 17th-century Rembrandt painting, "The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp."

That black hat was on display during von Hagens' controversial public autopsies of the early 2000s, begun not long after the first "Body Worlds" exhibit opened in Tokyo in 1995. In 2002, he courted not just controversy but possible legal action when he dissected human remains in front of an estimated 500 onlookers in London. United Kingdom authorities were nervous about the affair, as they warned von Hagens of vague charges if he went ahead with the dissection of an elderly man whom von Hagens said had donated his remains for the purpose. Authorities claimed that he was nevertheless in violation of the Anatomy Act, though von Hagens and his associates were never arrested. In fact, he returned to the same work within a few years, featuring dissections and his preserved bodies on a number of television programs.

Consent has gotten muddled in Body Worlds

Did the people whose bodies shock and awe visitors to "Body Worlds" really know what their remains would be getting up to? Gunther von Hagens and others who run the exhibits say yes. According to them, every single donor must give clear, written consent before their body is plastinated and put on display. Von Hagens has strenuously denied accusations that he's used the remains of executed prisoners or people with mental health concerns, as they could not reasonably give that consent and represent an ethical quagmire. Speaking to WHYY, Dr. Angelina Whalley, who is von Hagens' spouse, a "Body Worlds" exhibit curator, and the director of the Institute for Plastination, notes that a potential donor's consent can be revoked at any point before death. Donors also must die of natural causes, ruling out ethical gray areas connected to homicide or other potentially suspicious ends.

However, a deeper look at the matter of consent in "Body Worlds" reveals a more complicated reality. A 2006 report from NPR noted that the paper trail meant to legitimize the use of cadavers was difficult to follow, while the supply of remains involves middlemen who might still draw on unclaimed bodies. Even people who knowingly donate their remains to "Body Worlds" are eventually separated from their paperwork in an attempt to preserve their anonymity. However, this may work a bit too well, as it means that attempts to verify von Hagens' claims of legitimacy can only go so far.

It might be confused with another, even more controversial show

For anyone who isn't paying close attention, the plastinated corpse exhibits that they visit may all seem the same. But, while Gunther von Hagens and his team helm the "Body Worlds" show, there is a competitor with a far greater — or at least more obvious — stain on its reputation. That would be "Bodies ... the Exhibition," an unrelated show that has displayed plastinated remains since 2005. However, those bodies are unclaimed Chinese remains. That's proven to be ethically and legally thorny. When a Florida state review board asked the exhibit's organizers to provide documentation that the remains were obtained according to their ethical standards, they were met with reassurances ... but no actual documents, as board member Dr. Lynn Romrell told NPR in 2006.

Just two years later, "Bodies ... the Exhibition" organizers openly admitted that they couldn't quite say where their corpses came from. Neither could they confirm that the displays didn't include executed prisoners' remains. The New York State attorney general brought a case against Premier Exhibitions, which owns the "Bodies" exhibit, eventually eliciting the confession. After settling the case in 2008, Premier Exhibitions was forced to display signs at the entrance of its exhibit noting that the bodies inside might be from unconsenting people who were tortured and executed. Similar concerns nearly shuttered a 2017 "Bodies" exhibition in Prague, though the show was allowed to open despite the controversy.

Russian suppliers were charged with illegally obtaining bodies

Though Gunther von Hagens himself has never been found guilty of unethical behavior in a legal sense, some of his associates aren't quite so upstanding. In 2002, two Russian doctors were charged with illegally obtaining bodies without first getting the go-ahead from the deceased's relatives. The remains in question were part of a group of 56 bodies that were sent to von Hagens, which he was to plastinate and then return to the University of Novosibirsk. Von Hagens asserted that none of the remains were ever shown in a "Body Worlds" exhibit.

Just three years later, in 2005, Russian medical official Vladimir Novosyolov was convicted of illegally exporting remains, which allegedly included the bodies of prisoners, mental patients, and homeless people. Families members had reportedly been told that the remains were cremated and had to pay to receive the ashes — but whose ashes those were, we may never know.

Similar allegations have been linked to bodies sourced from Kyrgyzstan. Speaking to the Chicago Tribune in 2005, minister of Parliament Akbokon Tashtanbekov said that his visit to the national medical school (where remains were plastinated) revealed hundreds of bodies that had been taken from prisons and medical facilities. He was further disturbed by reports from people who said the bodies of their relatives were suspiciously missing. Von Hagens has repeatedly noted that he works with local partners to obtain remains, a handy level of removal that has kept him free of legal convictions.

Gunther von Hagens has been forced to deny bodies

Though Gunther von Hagens has so far avoided any legal woes himself, he does have some less-than-savory connections and has experienced a few awkward situations that undermine his claims of complete donor consent. Most damningly, German magazine Der Spiegel published a 2004 report that found a plastination facility he had set up in Dalian, China, was dealing in remains that may have come from unwilling prisoners. Most alarmingly, two bodies of a young woman and a young man each sported an execution-style bullet hole in their skull. Von Hagens later said that he had directed his Chinese employees to reject any remains that had been obviously executed, though he also admitted that he couldn't confirm exactly where the remains came from (via The Guardian).

Ultimately, seven remains in the same facility were also found to have suspicious head wounds. Von Hagens argued that the injuries were not from guns, however, and probably weren't of prisoners who had been executed by Chinese authorities. However, because he couldn't definitively prove his claims, von Hagens promised to return the remains to China. Ultimately, he opted to cremate the controversial remains instead.

Body Worlds has made some religious people recoil

Religious leaders and their congregations may find even more to worry about if a "Body Worlds" exhibition comes to their town. The displays have raised serious questions about the sanctity of the human body, especially when it comes to what should be done with one after the human in question has died. For many believers, the answer is clear: Leave those remains alone. In Gunther von Hagens' native Germany, the Lutheran church in Frankfurt once said that the display was an affront to human dignity. In 2007, some rabbis told Jewish News of Greater Phoenix Online that the exhibit violated fundamental tenets of their religion, including that humans are made in the image of the Almighty and, therefore, that the human body is sacred. Dissecting it, pumping it full of plastic, and charging living humans to see that body simply isn't kosher.

When a "Body Worlds" exhibit opened in Milwaukee in 2014, the Archdiocese of Milwaukee published a reflection paper that was arguably more even-handed, giving von Hagens' exhibit points for its educational value. However, the fact that fetuses were on display there raised concerns amongst abortion-wary clergy as to where, exactly, the remains had come from.

Others have been more unsure of their feelings, speaking to the tension between belief and science. As one visitor to a California "Body Worlds" show told CBS News in 2004, "Religiously, we feel the body should be respected and buried. I don't really feel that scientifically."

Science and art butt heads at Body Worlds

Gunther Von Hagens has declared himself a science educator, telling The BMJ that he is on a mission to democratize anatomy by putting remains on public display. "Respect is a matter of opinion," he said, but then said that, "With a whole body ... you can never forget that this is a former person."

Still, you'd be hard-pressed to claim that these shows are purely educational. Otherwise, why have dramatic figures like a corpse riding a rearing plastinated horse, or a person with an exposed brain playing chess? Likewise, many "Body Worlds" exhibits come with art, music, and quotes like those from Lebanese-American writer Khalil Gibran. Von Hagens has even whimsically deemed his main workshop the "Plastinarium." Then, there's von Hagens himself, with his ubiquitous black hat, references to Frankenstein, and general business sense (he makes money from his exhibits and selling plastinates, after all).

Ultimately, this means that "Body Worlds" lands in an uncomfortable middle ground between art, business, and science. What is the purpose of this exhibit — to inspire artistic awe, or to educate the public on anatomy? In 2010, Bishop Frederick Henry of Calgary noted just that, saying, "We have crossed the line from education into the realm of entertainment, questionable art and commercial showcases" (via CBC). For Henry, that was reason enough to call the whole thing off. But, for von Hagens and his supporters (including millions of exhibit visitors), that controversial in-between is precisely where they thrive.

Fetal plastinates can be unnerving

To many observers, plastinated adult human bodies are one thing, but the remains of much younger humans present a more difficult sight in a "Body Worlds" exhibit. Writing for The New York Times, reviewer Edward Rothstein was struck by fetal specimens on display during a 2013 visit, noting that it was hard to ignore the fact the fetuses each represented an individual death. Though Gunther von Hagens noted that the specimens were not made for the show but instead came from preexisting collections, the close quarters kept by new life and death made Rothstein and other visitors to this section extra uncomfortable. At a 2002 "Body Worlds" exhibit hosted in London, one man even threw a blanket over the body of a plastinated pregnant woman because he couldn't stand to see the preserved fetus revealed in her womb.

That uncomfortable pull between fascination and fear felt by many viewers may be behind the 2005 theft of a fetal specimen from a "Body Worlds" show hosted at the California Science Center in Los Angeles. Security cameras captured two women who appeared to work in concert to take the remains of a 13-week-old fetus out of a plexiglass case. A note left in an exhibit guest book may have been left by one of the thieves, as it referenced the missing specimen. However, beyond that, investigators had little to go on and couldn't seem to pin down the motivation for plucking the 4-inch fetus off display.

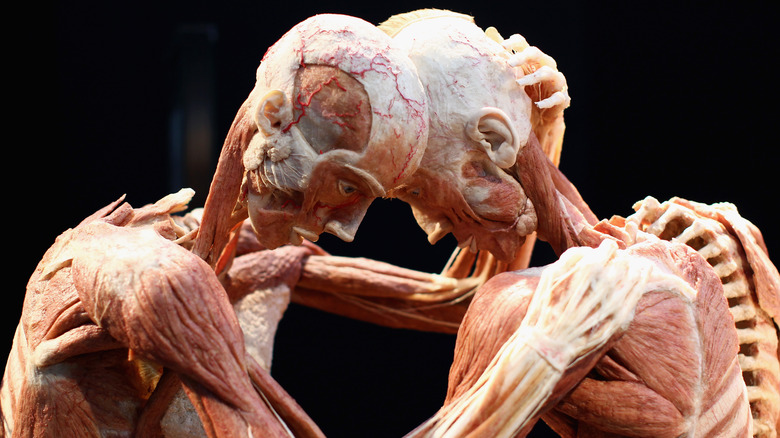

One explicit display has caused even more controversy

Debuting in Berlin in 2009 in the "Cycle of Life" "Body Worlds" exhibit, two plastinates depicted a female and male couple mid-coitus, with sections of their remains removed to give an especially close view of the act. Another pair, also male and female, was plastinated and cut into thin cross-sections. Gunther von Hagens said that the display was meant to push back against puritanical views that have kept sex and death out of education, but others weren't so accepting. U.K. politician Alice Ströver plainly stated that, "This couple is simply over the top, and it shouldn't be shown." Meanwhile, fellow MP Fritz Felgentreu commented, "I find it quite disgusting to use them in this way" (via The Guardian). Some German politicians were likewise unimpressed.

The German exhibition went ahead as-is, but "Cycle of Life" underwent serious editing before opening in Singapore. Chew Tuan Chiong, head of the Singapore Science Center in 2009, told Reuters that "sensational display of sexual activity does not go with our theme," though he signed off on including the less attention-grabbing cross-section of plastinated remains that had been posed similarly. Singapore is widely known for its conservative culture that has long been part of the city-state's system of governance.

That sort of backlash did practically nothing to stop von Hagens, who created more plastinates posed in the act, though exhibitions typically display the figures in a separate room and require that minors enter with an adult.

Body Worlds forces visitors to confront their own mortality

After a while, it may seem as if many of the objections levied at "Body Worlds" and Gunther von Hagens are a veneer applied over something else. Setting concerns about consent aside for a moment, which are vital in their own right, many of the other qualms come back to the same point: These are dead bodies. The man holding his own skin, the gymnast forever frozen on a balance beam, and even the plastic-infused cross-sections were all once living, breathing people. With poses unlike what you'll see in many modern textbooks, von Hagens' artistic approach makes that stark fact all the more clear.

It only takes a little extra thought for a viewer to consider how they might end up on the other side of the display. Like it or not, a trip to "Body Worlds" includes a confrontation with your own mortality. With his colorful approach to anatomy and exhibit-making, von Hagens says that he isn't just pushing viewers to gawk at a sideshow but to think more deeply and openly about death. Perhaps the visceral reactions to "Body Worlds" aren't simply about respecting human remains or religion but also a sign of squeamishness and even terror at the thought of facing the inevitable end. Supporters of "Body Worlds" might allege that this direct, unblinking view of death can help us reach acceptance of our mortality instead of constantly turning away until we suddenly can't.