The Best Batman Movie Is Not What You Think

Since 1943, Batman has had over a dozen major, starring appearances on the silver screen, from the original black-and-white serials all the way to 21st-century shared-universe blockbusters, and each one has a diehard fan-base willing to argue that their favorite is the best. Well, except for the serials. Looking back, we all pretty much agree those were terrible.

Every other adventure that's brought the Dark Knight to the screen, however, has a strong case for being the best. For the most part, it really depends on what you're looking for, whether it's the best villain, the best plot, the most striking imagery, the most brutal fight scenes, or even the most egregious ice puns, if that's your thing. With so many appearances, every one of them is the best at something, but there's only one that does everything better than the others, and it might not be the one you think. The best Batman film isn't The Dark Knight, it's not Tim Burton's 1989 Batman, and it's not even the Adam West Batman from 1966. It's the movie that takes what those movies do best and does it even better.

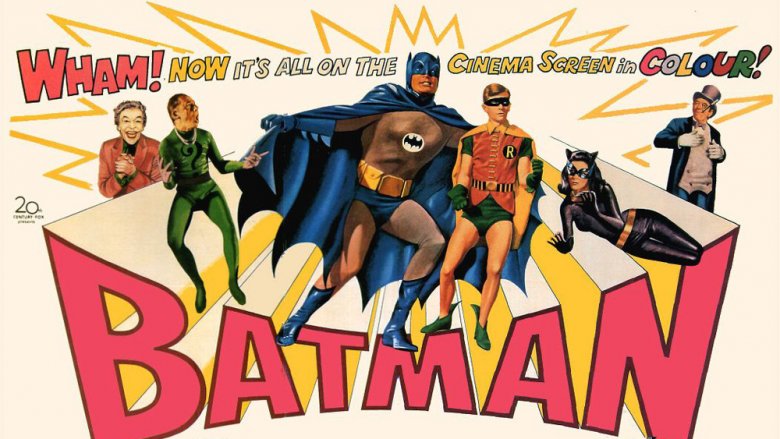

The case against (and for) Batman '66

To figure out which Batman movie is best, you can't just look for the best things about each of them. You have to take each movie as a whole, judging it by its flaws as much as you judge it by where it excels. You have to consider the intent behind the movie, and the legacy it left with audiences, and in that respect, it's pretty easy to argue that Batman '66 is in the top tier, even of superhero movies in general.

It does, after all, do an amazing job of accomplishing the goal of bringing to the big screen the things that made the live-action Batman TV show a hit. It juggled a massive team-up between four villains brought together as the United Underworld — who are referred to in the script as a monstrous rectangle, which is maybe the best way that four people have ever been referred to in a movie — and gave viewing audiences a taste of epic, sweeping adventure with scenes that involved Batman's custom helicopter and speedboat, a nuclear submarine, and an exploding shark. It even boasts some genuinely good emotional content in the form of Bruce Wayne's heartbreak when he realizes he's been trick-seduced by Catwoman.

Unfortunately, Batman '66 is also rooted firmly in the source material's campy approach to Batman. That's not necessarily a bad thing — the comedy is both intentional and genuinely hilarious, with Batman's ill-fated attempt to get rid of a bomb holding up as an amazing bit of physical comedy over 50 years later — but the actual superhero adventure at the heart of the story doesn't really hold up. The villains' attempt at vaporizing the international delegates of the United World is a satire to the point of being a farce, and to cap things off, Batman and Robin don't actually fix it at the end. Instead, they screw it up so badly that they decide to sneak out a window. It's a great movie, but maybe not the best portrayal of Batman.

Style and substance in the Tim Burton movies

Next up came 1989's Batman and 1992's Batman Returns, directed by Tim Burton. At the time, they were hailed by fans as a return to Batman's darker roots, but really, Burton was just doing Batman '66 with a coat of goth paint: brightly colored knockout gas and a wildly theatrical villain, goons in matching satin jackets, the satirical touches with the newscasters trying to avoid poisoned makeup. The "Penguin runs for mayor" plot in Batman Returns was lifted directly from one of the show's two-part adventures.

That said, you can't deny that Burton's gothic spin is a striking one. Anton Furst's designs for Gotham City are a beautiful nightmare of urban sprawl, with Art Deco facades rammed against industrial piping and vents. Returns in particular has some of the most striking imagery in the superhero genre, rendering a wintry Gotham as the monochromatic set for a morality play. The shot of Catwoman leering at a department store through the sneering logo of a cartoon cat etched on glass is a perfect example of how much style the Burton films had.

Unfortunately, they're also deeply flawed. The Batman we saw in the '89 film is an unhinged weirdo for whom heroism seems like a mostly unintentional side effect of a quest for vengeance that finds him casually murdering dozens of henchmen. Returns is even worse on that front, with a script that was Frankensteined together from multiple drafts, with the seams between them almost as glaring as the imagery on the screen. From a plot standpoint, it's a confused mess where the only character with clear motivation is Christopher Walken as an evil industrialist, and even then his motivation is pretty much just "be evil."

Joel Schumacher takes style to the extreme

If Burton's Batman films were marked by stylistic excess, then his successor, Joel Schumacher, took that idea to the extreme. Every element Burton played with in those movies is exaggerated in Batman Forever and Batman and Robin, and the most charitable way to refer to the results is "diminishing returns."

Schumacher's films took the influence of the '60s TV show and ramped it up to levels that went well past the '60s, including pun-spewing arch-criminals, femme fatale villainesses, and the introduction of Robin, who was adopted by Bruce Wayne despite the fact that Chris O'Donnell was pretty clearly in his mid-20s when these movies were made. Even Gotham itself was ramped up, from the designs that Furst described as "like Hell burst through pavement" to a bizarre cityscape with buildings held aloft by massive statues, where everything was soaked in kaleidoscopic neon light.

Needless to say, those movies have a pretty bad reputation, to the point where Schumacher apologized for them. Really, though,they're not that bad, especially the reviled Batman and Robin. Like Batman '66, it's a movie that knows exactly what it's doing and leans into its campy aspects. It's just not as good as that movie by a long shot, and even its most contradictory defenders will admit that "not that bad" is a long way from "the best."

The Dark Knight Trilogy's flawed masterpiece

When Batman returned to theaters in 2005, it really was the darker take that the Burton movies were mistaken for. It was still undeniably a superhero movie, with a plot that revolved around a secret ninja cult and a scheme to destroy Gotham City with fear gas, but it made an attempt at a slightly more grounded version of Batman himself. That alone makes it a weird movie to watch in the context of its sequels, which move through morality play into the straight-up fable that is The Dark Knight Rises, a movie where a flash drive can erase your criminal record and where every police officer in a city of millions can be trapped in a hole for six months by a wrestler in a CPAP mask.

Between them, though, is The Dark Knight, a movie that is justifiably regarded as a high point of the genre. Its tight, complicated plot is driven by Heath Ledger's incredible portrayal of the Joker, whose random "Agent of Chaos" persona is a smokescreen hiding a complex plot built around revealing the worst of human nature. It's a movie where Bruce Wayne loses by being unable to save the woman he loves, while Batman wins by showing that, if they have an example to show them the way, people can be something better than the violent mob the Joker paints them as.

The Dark Knight is easily the safe pick for the best Batman movie of all time, and with its compelling characterization and the intensity that Ledger and Christian Bale bring to their roles — not to mention Aaron Eckhart, who holds his own as a version of Two-Face who could not be further from Batman Forever's scenery chewing day-glo circus clown — it lives up to the hype. But it does have flaws, and its flaws feel magnified by how well it does everything else. Its ending is weirdly cynical given what comes after, and the bizarre bullet-reconstructing pseudoscience is goofy enough to feel completely out of place in the neat clockwork of the rest of the plot.

Batman v Superman v explosions

Finally, we're left with Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice, and in all honesty, compared to most of the other movies we've already been through, it's not even in contention. From the moment we're introduced to Batman in the context of DC's current cinematic universe, it feels like we're missing something, which is probably because we are.

Sure, we get the Waynes being murdered yet again, but by the time Superman is failing to save anyone in Metropolis, this is a Batman who has apparently already been through a long career that includes the death of a Robin and fighting enough villains that they can form an entire Suicide Squad. That's all stuff that we might want to see to get an idea of why we should like this Batman before he's effortlessly manipulated into a superhero fistfight by Lex Luthor, but we don't get it. Instead, this is a Batman who's coasting on all the movies that came before him — along with imagery lifted directly from Frank Miller's The Dark Knight Returns — and the assumption that we should already know everything about this guy and what his deal is. That's a lot of assuming when you're telling the story of what's ostensibly a brand-new Batman who's meeting Superman on a movie screen for the very first time.

What the Batman of BvS does have going for him is a handful of bone-shattering fight scenes and the foresight to be the mastermind behind putting together the Justice League, even if Lex Luthor seems to be the one who did the homework on that one.

So if none of these are the best Batman movie, what's left? The one that does it all well: Batman: Mask of the Phantasm.

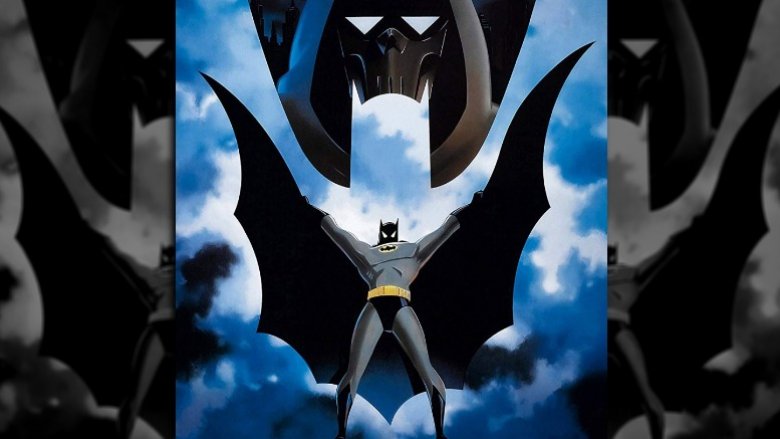

Mask of the Phantasm: the best Batman film

It's worth noting right from the beginning that Mask of the Phantasm isn't perfect. It was originally planned for a direct-to-video release, and the decision was made for the movie to hit theaters on Christmas Day 1993 well after it was already in production.

It shows, too. Not only were audiences treated to a resoundingly bad trailer that looks like it was put together in an afternoon, Mask of the Phantasm frequently falls short in the way it looks. The animation of the film is far from the crisp visuals that audiences might've expected in an era where animated movies were defined by the Disney Renaissance, but there's a reason for that. Just look at Aladdin, which had been released the year before. When the chairman of Disney Studios demanded a full rewrite in April 1991, only 19 months before the film's scheduled release, it was such a big deal that the animators referred to it as "Black Friday." Mask of the Phantasm, on the other hand, had a total production time of only eight months and had to contend with making a movie meant for standard-definition VHS tapes look good enough for the big screen.

But that doesn't mean you have to grade Mask of the Phantasm on a curve. For all its shortcomings, it really does do everything the other movies attempt, only better. Like...

Bringing the Animated Series to the big screen

Batman: The Movie succeeded in bringing what worked on TV to an epic adventure on the screen, and the Burton films were marked by a distinct and definitive visual style that worked beautifully for Batman and his world. Mask of the Phantasm managed to accomplish both those feats, but without the flaws that the 1966 and 1989 movies had to contend with.

Part of that, of course, comes from the fact that they're working with entirely different source material. While Batman '66 was rooted in producer Lorenzo Semple Jr.'s notion that superhero comics were an inherently silly genre that could work as a comedy just by presenting them as if they were serious — with '89 following in its footsteps — Mask of the Phantasm was building on the foundation that its producers had already laid down with Batman: The Animated Series. This was a show where the idea was to strip Batman down to the bare necessities of what worked, embracing moodiness and character rather than camp, and the movie takes those ideas to the next level.

That translated to the visual style, too. While the animation was a little bit lacking, the BTAS designs of a retro-futurist Art Deco Gotham City were beautiful on the big screen, and Mask of the Phantasm put them front and center. The extended "City of the Future" sequence and the climactic battle between the Joker and Batman where they rampage like kaiju through a scale model of the city are fantastic showcases for the revolutionary style that would define DC's animated universe for the next two decades.

Emotional content

The Nolan movies succeed largely because we're shown Bruce Wayne as a flawed human being who transcends himself to become something more, and the sacrifices he endures to pursue a life as Batman. Mask of the Phantasm brings in those same elements, but in a way that balances and blends its emotional core with superheroic action.

The scene in the graveyard, where a younger Bruce Wayne pleads with his parents to forgive him for breaking the vow he made as a child to avenge their deaths stands up against any emotional scene in any other Batman film. The way he's tortured by the fact that keeping that vow would mean giving up the only happiness he'd felt since their murder is a fantastic illustration of the tragedy at the center of his character, and for an audience that had primarily seen Batman as an unstoppable ideal who drove around in rocket cars and swung from grappling hooks, it added layers.

What it does best, though, is an element the other movies often struggle with. In presenting the Phantasm, it shows the difference between a quest for vengeance and a search for justice. Andrea Beaumont has every reason to hate the people she's going after, just as Bruce Wayne does, but as much as we can understand her, there's a clear distinction between hero and vigilante.

Origins and influence

One of the more interesting things about Batman: The Animated Series was that while it gave origin stories to a few villains like the Riddler, Batman himself — along with the Joker, Catwoman, the Penguin, and others — arrived fully formed. That works great on the show, but the movie allowed them to explore Batman's early days in a way that feels different.

Like Batman Begins, which drew on Frank Miller and David Mazzucchelli's Batman: Year One, it lifts its inspiration heavily from the page. In this case, though, elements of Year One are combined with the plot of Mike W. Barr, Alan Davis, and Todd McFarlane's Batman: Year Two, in which the Dark Knight takes on a villain who bears more than a passing resemblance to the Phantasm. Unlike Begins, however — and unlike Batman v Superman's attempts at recreating Dark Knight Returns — it doesn't just do a movie version of something that had already been done. Instead, it mixes those elements together in a new way, combining them with the stripped-down aesthetic and direction of the show for something that feels truly unique.

It's a movie that's full of bold choices, showing Batman's human weaknesses, giving him a villain who ultimately gets away, and using the Joker only as a secondary threat that looms over what is ultimately a very personal story. It takes risks no other Batman movie has, and in almost every case, they pay off, at least in terms of narrative. Sadly, Mask of the Phantasm was the only Batman movie ever to flop on its initial release, but the years since have seen it undergo a critical reexamination that has placed it right where it should be: at the top tier of Batman's cinematic adventures.