Who Was Civil War Spy Antonia Ford Willard?

James Bond and Jason Bourne movies might make it seem like spycraft and espionage are relatively modern developments. Spies have been around for centuries, though, and have played a pivotal role in historical world events. In the 16th century, Queen Elizabeth I had spies, and intelligence gathering was crucial to the outcome of the American Revolution. Meanwhile in the 1860s, spies also had an important role to play in the American Civil War, for both the Union and the Confederacy.

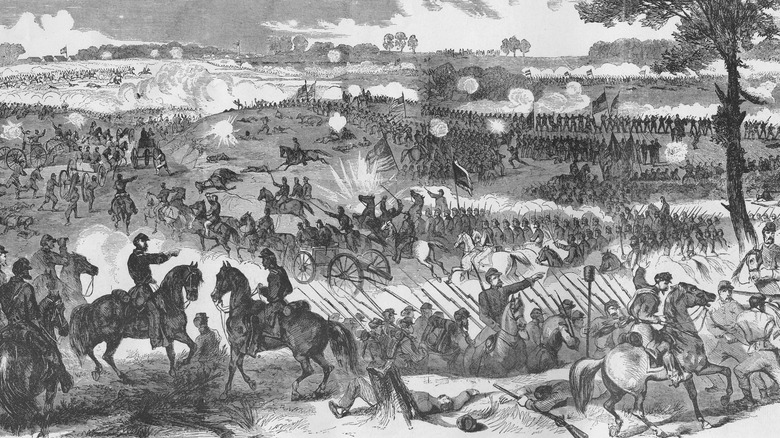

The espionage work of one Confederate spy, Antonia Ford Willard, notably affected the First Battle of Bull Run and Second Battle of Bull Run (above), sometimes called the Second Battle of Manassas, both Southern victories. And Ford's cloak and dagger was also possibly involved in the capture of Union General Edwin H. Stoughton by Confederate forces the next year, according to the History of American Women. For her work in intelligence gathering, Willard — born Antonia Ford in Virginia — was arrested in 1863 and sentenced to the Old Capitol Prison, in Washington D.C.

In a twist, while she was in D.C., she began a romantic relationship with Major Joseph Clapp Willard of the Union Army, a married man who escorted Ford north as a prisoner. Not long after her sentencing, Ford was released, but after returning home to Virginia, she refused an oath of loyalty to the Union and was sent back north as a prisoner. Willard, whom she later married, helped secure Ford's freedom for a second and final time.

Her family had Southern sympathies

Antonia Ford was born in 1838 in Virginia and her father, Edward R. Ford, was a successful businessman who supported the Southern cause. Her brother also died in the Battle of Brandy Station, fighting for the South. In 1861, the Ford's family home in Fairfax, Virginia was occupied by the Union Army, and during this period — the First Battle of Bull Run — Ford surreptitiously passed intel gleaned from Union soldiers to Confederate General J.E.B. Stuart's forces, encamped nearby.

For her loyalty, Ford grew close to General Stuart and became one of his most trusted informants, designated his lieutenant and aid-de-camp. In 1862, Ford rode 20 miles to inform Stuart the Union army had planned a trap. According to Ford's intelligence, federal forces plotted to lure the Confederate army out of position with its own colors in what became the Second Battle of Bull Run, according to Emerging Civil War. In that battle, Confederate General Robert E. Lee defeated the Union army.

Afterward, the North continued to occupy Fairfax, and accordingly, Ford's work as a double agent continued. By 1863, Ford had endeared herself to Union General Edwin H. Stoughton, who commanded federal forces in the area. The two were known to spend time together, despite the Ford family's well-known support of secession. The Union official even hosted a party for Ford's mother and sister. Under the cover of that distraction, Confederate forces slipped into Fairfax unnoticed. A Ford rendering from "Harper's Weekly" in 1863 can be seen above.

[Featured image by Harper's Weekly via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled | CC BY-SA 4.0]

Stoughton was captured, possibly aided by Ford's intelligence

The night of General Edwin H. Stoughton's party, Confederate soldiers led by Colonel John S. Mosby (pictured) captured the Union general, nearly 60 horses, and took more than 30 prisoners. Word spread that information Antonia Ford passed to Southern forces may have helped it happen. Under suspicion, Union Secret Service head Lafayette Baker devised a gambit to entrap her, using his own female double agent posing as a Confederate refugee and planted in the Ford family home to convince Antonia to reveal her secrets.

Once found out, Ford was arrested, taken to Washington, and thrown into the Old Capitol Prison. In "Prison Life in the Old Capitol and Reminiscences of the Civil War," James J. Williamson wrote about what life was like at the facility: "Prisoners in the Old Capitol were mostly civilians, except where soldiers (either prisoners of war or men charged with offenses), were brought in and kept until they could be sent to places designated; or prisoners from other prisons held over until they could be shipped South for exchange."

The book also describes what conditions for Ford may have been like. Cells were "small, close and ill-ventilated, and here we are kept penned up, with the exception of the time we are allowed out at meal times. Then we are out in a damp yard, which is so crowded when there is a large number of prisoners here ... In this yard we stand for about a half-hour, consequently nearly all of us are troubled with colds."

Ford convinced Major Joseph Clapp Willard to get divorced

After two periods spent captive at the Old Capitol Prison, Antonia Ford (pictured) was released with Major Joseph Clapp Willard's help, and he finally convinced to take an oath of loyalty to the Union. As mentioned, during her time in D.C. she became romantically involved with Willard, a Union officer who accompanied Ford as a fugitive on her journey north. Willard, who was Ford's elder by nearly 30 years, even transferred to Washington in an effort to secure her freedom, possibly motivated by his own feelings for the young woman.

Notably, General J.E.B. Stuart and Colonel John S. Mosby denied Ford was involved in the Stoughton raid, and although she was a known Confederate informant, the evidence of Ford's involvement in Stoughton's capture was largely circumstantial. Ford and Willard's relationship continued after her release, with one complication: Willard was married. By 1864, one year before the end of the conflict, Willard divorced his wife at Ford's urging, left the Union, and joined her in Fairfax, where they wed. Ford's health likely never recovered from her time spent in prison and she died young, seven years later, at the age of 32 in D.C.

[Featured image by O.H. Willard via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled]