Messed Up Things That Happened During The Trojan War

"War is hell," as General William T. Sherman once reportedly said. In war, people kill, get killed, and commit all sorts of atrocities against combatants and non-combatants alike in the frenzy of the fighting, including massacres, looting, sexual crimes, and more. And often, the combatants will stop at nothing to win. The Trojan War, the mythical story of the Greek Bronze Age siege of Troy, is no exception.

What is considered "acceptable" in war has changed in the 3,000 years between Bronze Age and classical Greece and modern times. Nevertheless, there are a number of incidents during the Trojan War in which ancient and modern sensibilities align — cases in which the "heroes" of the Trojan War went way too far by any standard.

There are numerous unheroic actions on the parts of the combatants at Troy, ranging from violations of guest-host rules to sex crimes against innocent women and the unrepentant murder of children to achieve political or strategic ends. Here are some of the messed-up incidents that earned the warriors of the heroic age the wrath of gods and men and, in many cases, led to their demise.

The kidnapping of Helen

Before the Trojan War starts, Trojan prince Alexandros Paris arrives in Sparta to seek out his promised bride Helen, the "most beautiful woman in the world." He has to take her from the Spartan palace she shares with her husband Menelaus — and he takes full advantage of his host's hospitality to make it happen.

The tradition behind this episode comes from a later work called the "Cypria," which survives as quotations in the work of later authors. Paris arrives in Sparta, where Menelaus, in full accordance with the Greek practice of xenia — a divinely sanctioned practice of welcoming strangers into one's house — receives him warmly. Paris responds with lavish gifts for Helen. When Menelaus leaves for Crete, he orders his wife to see to the every need of their Trojan guests.

The next part is the truly messed-up part. Not only does Paris kidnap Helen, but he also takes a large amount of Menelaus' material property. Helen also allegedly took her son Pleisthenes, presumably a child of Menelaus, with her. Paris and Helen go on to conceive a son of their own named Aganus. So to summarize, Paris steals his host's wife and property after he treats him like an honored guest, gets his host's wife pregnant, and also makes off with his host's son. Menelaus, understandably upset, goes to his powerful brother Agamemnon, and they assemble a host to destroy Troy in revenge. According to Herodotus, Egyptian tradition held that a number of Paris' servants were so disgusted with their lord's actions that they refused to return to Troy with him and denounced him to the priests of Thonis, "the warden of the Nile mouth."

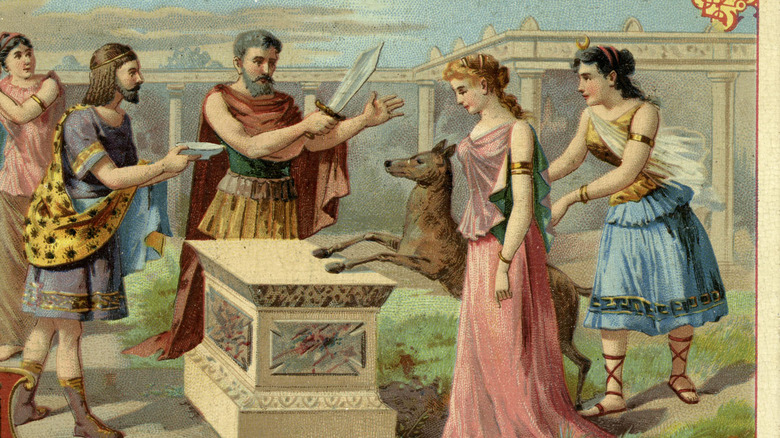

The sacrifice of Iphigenia

Human sacrifice is generally considered a repulsive institution to modern sensibilities, but in the ancient world, it happened — even in the "heroic age" of the Mycenaean Greek world when the Trojan War took place. In fact, according to later Greek tradition, the entire Trojan War was made possible due to the sacrifice of a virgin princess of Mycenae: Iphigenia, Agamemnon's eldest daughter.

The playwright Euripides' "Iphigenia in Aulis" states that before the Greeks could sail to Troy, they had to sacrifice Iphigenia to get a fair wind, as the army prophet Calchas foretold. But Agamemnon knew his wife, Clytemnestra, would never consent, so he tricked her and Iphigenia by saying that Iphigenia was to be married to Achilles.

Clytemnestra arrives in Aulis with Iphegenia for the wedding. However, when Achilles has no knowledge of the alleged wedding (he was tricked too), the truth comes out that Iphigenia is to be ritually murdered. Clytemnestra highlights a particularly screwed-up part of the episode, noting that her daughter will be killed to recover a faithless woman (Helen) who will be able to return to Sparta and continue life with her own daughter Hermione as if nothing had ever happened. Iphigenia begs her father to spare her or at least give her one last kiss, but to no avail. Agamemnon is unmoved and sacrifices Iphigenia — all to start a war for the faithless Helen. The ancients were so disgusted with this episode that the Roman poet Lucretius summed it up in his "De Rerum Natura" as one of the "crimes to which Religion leads."

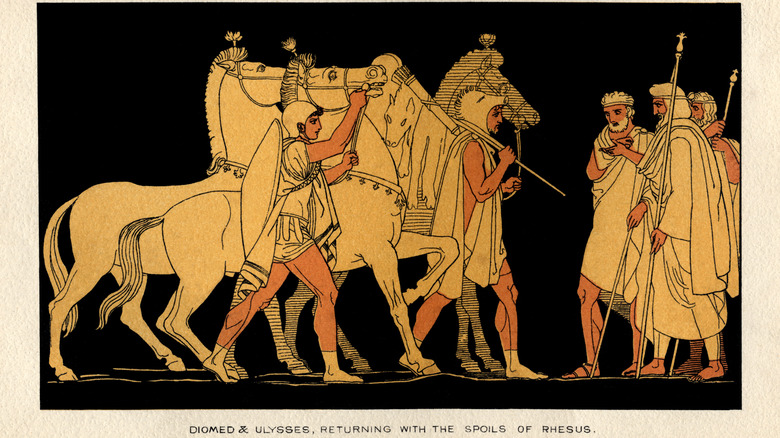

Dolon betrays his countrymen

This one is more messed up from the point of view of the contemporary Mycenaean warrior culture rather than modern standards. To set the scene, Book X of the "Iliad" (year 10 of the war) sees the Greeks send the kings of Ithaca and Argos — Odysseus and Diomedes, respectively — to spy on the Trojans and find out whether they intend to withdraw or attack the Greek camp. The Trojans, meanwhile, send their own man — one Dolon — to spy on the Greeks. The Trojan promises Hector, "I will make you a good scout, and will not fail you."

Dolon fails miserably, as the two Greeks catch him in between the opposing camps. His bravado gone, he begs and turns on his commander, saying, "[Hector], with his vain flattering promises, lured [him] into derangement." He also crucially spills all the details about the Trojan camp, including the positions of all the allied contingents and how to infiltrate them. In doing so, he betrays his people, his city, and his comrades — a gross violation of the heroic warrior code of death over dishonor.

Dolon's information proves fatal to Troy's cause. He reveals that a powerful Thracian army under King Rhesus has arrived to assist the Trojans. Diomedes and Odysseus, aided by the goddess Athena, go to work, slaughtering a handful of Thracians, including King Rhesus, and stealing the king's horses. Leaderless, the Thracians withdraw back to Europe. The two Greeks also kill Dolon, noting, in a nutshell, that once a traitor, always a traitor.

Achilles' desecration of Hector's body

Among the best-known episodes near the end of Homer's "Iliad" is Greek warrior Achilles' mistreatment of Trojan prince Hector's body. In Book XXII, during the war's final year, Achilles kills Hector out of vengeance for the latter's killing of Achilles' best friend Patroclus. Achilles is merciless to his Trojan rival even in death. As Hector is begging the Greek to return his body to his parents — King Priam and Queen Hecuba of Troy — Achilles mocks him, telling Hector that no amount of gold or begging will save Hector from becoming fodder for birds and dogs.

Achilles then ties Hector's body to his chariot and drags it around the city as Hector's parents look on in anguish. The text itself suggests Achilles' treatment of his dead rival has gone too far by focusing on the reactions of Hector's parents and wife, Andromache. In her motherly love and grief, Queen Hecuba "tore her hair and from her flung far her gleaming veil and uttered a cry exceedingly loud at the sight of her son." Andromache faints at the gruesome sight.

In the end, King Priam visits Achilles personally in Book XXIV so he "may have shame before his fellows" over the "foul" treatment meted out to Hector's body and return it for burial. Achilles initially mocks Priam, whom Homer describes as "godlike," further suggesting that his conduct toward Hector's body has been atrocious. In the end, however, Achilles grants a nine-day truce for Hector's burial, and the body is returned to Troy for a proper funeral. With that, the "Iliad" ends.

The cruel death of King Priam

Completing his role as the destroyer of Hector's family, Achilles' son Neoptolemus claims yet another two victims in the saga of the sack of Troy. King Priam of Troy is an old man by the time the Greeks break into his city and destroy it. As the Greeks are looting their way through the city, Neoptolemus finds Priam with his youngest son Polites, who is but a small boy.

The dark story of Priam's death comes from a much later tradition: Book II of the Roman poet Virgil's "Aeneid." The epic states that Polites runs for his life through the palace as a bloodthirsty Neoptolemus (whom Virgil calls "Pyrrhus") pursued and mortally wounds him. The boy dies before his father, who calls Neoptolemus' actions a "crime and impious outrage." Priam then berates Neoptolemus, noting that his father, Achilles, whom he refers to as Neoptolemus' "pretended sire," was a better man than his son.

Priam makes one last feeble attempt to protect himself, hurling a spear at Neoptolemus, which, unsurprisingly, bounces off the attacker's shield. Achilles' son, unashamed, responds, "Take these tidings, and convey message to my father, Peleus' son! Tell him my naughty deeds! ... Now die!" But the Greek does not simply kill the old man — he drags him by the hair bleeding through the corridors of his palace, sliding over the blood of Polites. He then runs Priam through the heart with his sword. According to Virgil, Priam's body was dismembered and never buried — an unfitting end for a king who had served his land and people so well.

The killing of Astyanax

After gaining entry into Troy via the trick of the Wooden Horse, the Greeks set about plundering and burning the city while massacring its inhabitants — and according to later post-Iliadic tradition, it appears they did not spare even the youngest male inhabitants of the city.

The messed-up event here is the killing of Trojan prince Hector's son Astyanax. Greek historian Apollodorus' version of the events is short: The Greek warriors snatched Astyanax, who was just a baby, and hurled him from the city walls. There are no details regarding the responsible party, although other traditions identify the culprit as Odysseus, who argued that killing Astyanax was necessary to prevent him from avenging his father and city.

Another version of the story comes from the so-called "Little Iliad," a lost epic that only survives in fragments. In this telling, Neoptolemus, the son of Achilles, is searching for Hector's widow, Andromache. He finds her with her baby, Astyanax, and the child's nurse. Neoptolemus seizes the child by the foot and hurls him off the tower. There are multiple messed-up things in this version. First, as is common to both versions, a baby is murdered. In the second, however, it underscores the humiliation of Hector's family at the hands of Achilles. It is Achilles who kills Hector. His son then completes the destruction of Hector's family by eliminating his line with the killing of Astyanax.

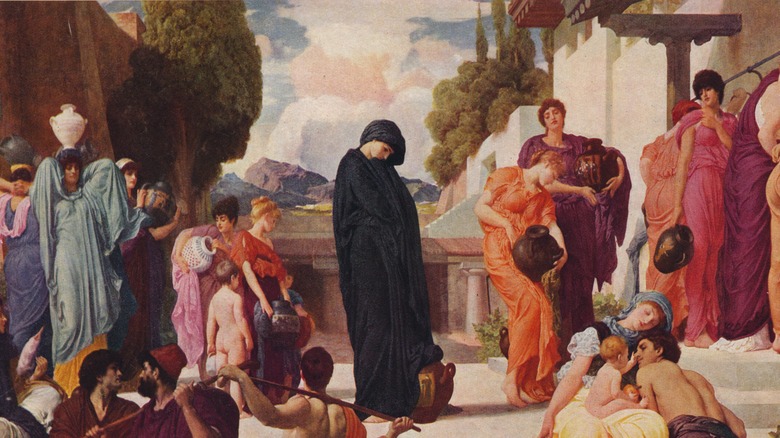

The taking of Andromache

Having already suffered the death of her husband Hector at the hands of Achilles, Andromache endures a second blow at the hands of Achilles' son Neoptolemus, who, in the "Little Iliad," throws her infant son Astyanax off the walls of Troy. But her humiliation does not end there. In the "Little Iliad," Neoptolemus completes his humiliation of Hector by taking "well-girded" Andromache back to Greece as his concubine. The fragment, however, is short on details, so later Greek tradition in the form of Euripides' play "The Trojan Women" fills in the gaps of what the scene might have looked like.

The tradition on which Euripides based his play depicts Neoptolemus cruelly dragging Andromache away from her homeland as she wails in despair. She is not allowed to visit her dead husband's grave, and perhaps most messed up of all, she is not even permitted to bury the body of her young son.

Ultimately, she is forced to go to Greece with Neoptolemus, and traditions vary as to her fate. Greek travel writer Pausanias writes that her captor — also known as Pyrrhus — decided to go live in Epirus, where she bore him three children named Molossus, Pielus, and Pergamus. Euripides' play "Andromache" only lists Molossus, but does not rule out the existence of other children. After Neoptolemus was murdered at Delphi, she married her brother-in-law Helenus and had a child with him. It is unclear whether she played any role in Neoptolemus' killing.

The sacrifice of Polyxena

Polyxena, the daughter of Troy's king and queen Priam and Hecuba, was nothing short of a Trojan beauty, described in later tradition by Dares the Phrygian as "fair, tall, and beautiful" with "her hair blond and long, her body well-proportioned, her fingers tapering, her legs straight, and her feet the best." Achilles falls in love with her after seeing her and even proposes that King Priam of Troy give her to him in marriage in return for withdrawing his soldiers from the siege.

Hecuba and Priam refuse Achilles' offer and instead turn her into bait to draw him to his death. Dares writes that Priam uses the promise of Polyxena to lure Achilles into the temple of Apollo, where Paris kills him. There is no indication she is aware of the plot. After the sack of Troy, Achilles' son Neoptolemus makes Polyxena pay for her role in the death of his father. As the Greeks are waiting for fair weather, the army seer says that they will need to sacrifice another girl. Neoptolemus, per Dares, cuts Polyxena's throat — as if she were an animal — on Achilles' grave to placate the dead and obtain a fair wind.

The ancients saw the sacrifice of a pure, innocent girl as wrong. Nevertheless, the playwright Euripides still managed to put a heroic spin on Polyxena's death. In that tradition, the Trojan princess went to her death willingly, preferring a pure death over the dishonor of captivity and concubinage in a hostile land.

The death of Polydorus

The story of Polydorus, one of Trojan King Priam's younger sons, is one of those in which two contradictory traditions exist, resulting in wildly different narratives. The Homeric version, as told in Book XX of the "Iliad," states that he was Priam's youngest son and is killed by Achilles on the battlefield. Not a particularly nice story, but at the end of the day, it's a battlefield death — one among many.

The tradition told in Greek playwright Euripides' "Hecuba," however, is very different and much darker. In the play, Polydorus enters as a ghost (so he's already dead) and recounts that Priam sent him away from Troy once the Greek attack began for his safety. Priam sent the boy to his "guest-friend," the Thracian King Polymnestor, along with a substantial amount of gold. There, Polydorus spent the war in safety, growing into a happy, healthy child.

When the war ends after 10 years, however, Polymnestor does not release the boy or keep him around. Instead, according to Euripides, Polymnestor has him murdered so he can keep the gold Priam had sent along with him. His body is tossed into the sea. The murder would have been a blatant violation of the practice of xenia – the Greek tradition of welcoming and protecting strangers and guests. Given the fact that Polymnestor is called a "guest-friend" of Priam, his murder of Polydorus, who was just a boy, comes off as especially criminal.

The fate of Cassandra

Priam's daughter, Cassandra, as Quintus of Smyrna recounts in his "Fall of Troy," was endowed with the power of prophecy. Her words were always the "utter truth." The only problem was that no one ever believed her, as was "Fate's decree." So when the Greeks entered Troy with the Wooden Horse, Cassandra was one of two people to see through the ruse.

Cassandra attempted to warn her countrymen, prophesying that the horse would bring fire and death upon the city. Instead, they accused her of being controlled by a "raving tongue of evil speech." She then tried to set the horse on fire with a burning staff and hack at it with an axe, but was restrained.

Ultimately, Cassandra became a victim of her countrymen's stubbornness and the Greeks. Later Greek historian Tryphiodorus and most authors generally agree that during the sack of Troy, the seer sought shelter in the temple of Athena — a sacred, inviolable place. But then the stories diverge. Dictys Cretensis says that Ajax of Locris dragged her out of the sanctuary. Tryphiodorus, on the other hand, says that he also raped her inside the temple. This second act — the violation of a priestess seeking sanctuary before a goddess — was a "reckless sin" and "deed intolerable" per the goddess herself, according to Quintus. At Athena's request, Zeus sends a storm that kills Ajax on the way home. Things did not improve for Cassandra, who according to Pausanias, was given to Agamemnon to live as a captive in Mycenae. There, according to Pausanias, Agamemnon's wife Clytemnestra murdered her and her twin boys.