Conspiracy Theories Surrounding Warren G. Harding's Death

President Warren G. Harding was on a whirlwind national tour in the summer of 1923 when he suddenly died in a hotel room in San Francisco. His wife, Florence, was reading to him as he lay in bed when a "shudder ran through the president's frame and he collapsed" on August 2, according to The New York Times. While Harding's sudden death shocked the nation, it was a series of incidents and accidents in the wake of this tragedy that set off a firestorm of rumors of foul play that haunted his death for decades.

Among these occurrences was a series of contradictory statements made by his doctors and others following his death, according to Smithsonian Magazine. Things only got murkier after first lady Florence Harding strenuously objected to an autopsy on her husband, and a con artist and former federal agent then accused her of murdering the president in a salacious book published seven years after the president's death, per PBS.

Mixed signals

President Warren G. Harding had been sick in bed at the Palace Hotel in San Francisco since July 29. He blamed his symptoms, which included shortness of breath and indigestion, on a bout of food poisoning. At the time, five physicians were involved in his care. On the morning of August 2, the doctors sent out a positive-sounding bulletin. "While recovery will inevitably take some little time, we are more confident than heretofore as to the outcome of his illness," they wrote, per the Associated Press.

They couldn't have been more wrong — Harding died that night. Afterward, doctors and government officials compounded the problem with conflicting accounts of his last moments. "There have been several versions of the incidents surrounding the death of President Harding," a reporter for The Dayton Herald wrote a few days after the president's death. "The shock and resulting confusion prevented those immediately concerned in the final scene in Mr. Harding's bedroom at the Palace Hotel taking note of the actual occurrences."

Florence Harding

President Warren G. Harding's doctors listed his death as being due to "cerebral apoplexy" — a stroke — brought on by "an acute gastro-intestinal infection," the Associated Press reported at the time. The cause of death was just a best guess since Florence Harding made it clear she would not allow an autopsy on her husband.

"We shall never know exactly the immediate cause of President Harding's death since every effort that was made to secure an autopsy met with complete and final refusal," Dr. Ray Lyman Wilbur, who had attended the president while in San Francisco, later wrote (via the National Constitution Center). Besides disallowing an autopsy, Mrs. Harding had her husband embalmed an hour after he died and then burned his personal papers. Florence Harding's behavior left open the door for speculation that she had poisoned her husband. A con man named Gaston Means took this rumor and ran with it.

The confidence man

Gaston Means started out as a private detective. During this time, he learned the skills he'd eventually use to enrich himself through extortion and bribery while a member of the Bureau of Investigation (the precursor to the FBI) during Prohibition. He was also suspected of murder and spied for Germany during World War I. After serving three years in federal prison for a few of his many misdeeds as a federal agent, he wrote "The Strange Death of President Harding," in which he alleged Florence Harding admitted killing her husband with poison.

The reason, according to Means' book, was to save the president's reputation. "Had he lived twenty-four hours longer — he might have been impeached," Mrs. Harding allegedly told Means. "Nothing — nothing could stem the torrents that were pouring down on us. ... I have no regrets." While Warren Harding's administration had its share of scandals, Means' story was debunked by the book's ghostwriter, May Dixon Thacker, after the con man stiffed her on her cut of the book's royalties, per PBS and Warren G. Harding Presidential Sites.

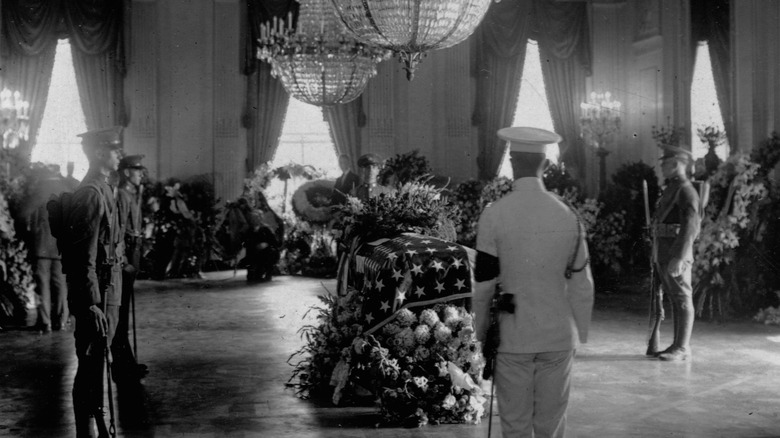

[Image via Library of Congress Prints & Photographs Division | Cropped and scaled]

Administration scandals

The biggest scandal to plague President Warren G. Harding's presidency involved a bribery scheme by Secretary of the Interior Albert Fall. Harding appointed Fall, and in doing so he unwittingly helped facilitate the Teapot Dome scandal in which Fall and his cohorts received kickbacks from oil companies in return for leases on Navy-owned oil reserves. Some people theorized Harding's death could have been related to Congress' investigation into the administration and that he was perhaps murdered by those involved — or died by suicide to avoid the scandal.

Harding's personal scandals didn't come to light until after his death and involved his many affairs before and during his time in office. He had an ongoing affair with his secretary, Nan Britton, which resulted in an alleged illegitimate child and a tell-all book by Britton, according to Salon. He also had a decade-long affair with an Ohio woman named Carrie Phillips before becoming president, per Warren G. Harding Presidential Sites. These revelations also fueled conspiracy theories that Florence Harding might have murdered her husband over his philandering.

Heart problems

Today, it's generally accepted that Warren G. Harding died from a heart attack related to congestive heart failure — not foul play. In the 1920s, cardiology was still a relatively new field, and without permission to perform an autopsy, Harding's doctors were flying blind. And they were also victims of the many conspiracy theories floating around.

"We were accused of starving the President to death, of feeding him to death, of assisting in slowly poisoning him, and of plying him to death with pills and purgatives," Dr. Ray Lyman Wilbur recalled (via the National Constitution Center). "We were accused of being abysmally ignorant, stupid, and incompetent, and even of malpractice." One more recent theory actually does lay some blame for Harding's sudden demise on one of his attending physicians, a homeopathic practitioner named Charles Sawyer who often gave the president powerful laxatives — purgatives — of his own formulation. In his book "Florence Harding: The First Lady, the Jazz Age and the Death of America's Most Scandalous President," presidential biographer Carl Anthony wrote that Sawyer may have accidentally done Harding in with "a final, fatal overdose of his mysterious purgatives, pushing the man's already weakened heart into cardiac arrest."