Wild True Stories Of Wine Fraud

Occasionally, an extremely bizarre and high-profile case of wine fraud makes headlines. But unbeknownst to most people who aren't enthusiasts, collectors, or professionals, it is actually a shockingly common scam that can happen with any wine — whether it was bought at private auction or the supermarket.

Sometimes con artists are able to trick potential buyers and investors into buying bottles that they've never seen, but to fool a more savvy collector, scammers have to create a believable fake. Wine fraud generally involves passing a cheaper wine off as a more expensive vintage to trick someone into purchasing it. Some scams rely on the inexperience of the buyer, but others can be incredibly advanced and even experts may struggle to tell if they're looking at the real thing. In fact, it's believed that more than 5% of wine bottles sold at auction are fakes. As described by an article in Seven Fifty Daily, to try to detect a fake, experts carefully inspect the labels for signs that they aren't actually as old as they appear to be, looking at everything with a magnifier or under UV light. They also inspect corks for signs of tampering, in case they have been removed and put back in.

There have been documented complaints about wine fraud for almost 2000 years. These are just a few of the strangest stories.

Dr. Conti

In the early 2000s, Rudy Kurniawan established a reputation as a wine connoisseur and became a regular at auctions for expensive and rare vintages. He was particularly well known for buying large quantities of Domaine de la Romanée-Conti, earning him the nickname "Dr. Conti." At one auction in 2006, he sold more than $24 million worth of wine — more than anyone had ever sold in a single wine auction by a considerable margin. Over time, however, certain wine collectors, including billionaire Bill Koch, began discovering fraudulent bottles in their collections. Dr. Conti was scamming them all.

Koch had purchased more than 200 bottles from Kurniawan for more than $2 million, and was rankled by being scammed. He used his considerable wealth and influence to lead an investigation into Kurniawan. In 2012, the FBI raided Kurniawan's home and discovered a highly advanced setup for creating counterfeit wines, complete with all the equipment he needed to fool the experts. His primary method was putting cheaper wines into pricier bottles. While they might not have tasted right, most extremely valuable wines are never actually drunk, just kept in collections, so in many cases any difference in the flavor might never have been detected.

In 2021, Kurniawan was ordered to pay back millions of dollars to seven collectors he had tricked and was deported to Indonesia. During his career, he sold thousands of bottles, and it's highly likely that many of his frauds are still hiding in private collections.

Supermarket fakes

Most publicized cases of wine fraud involve cheap wines being passed off as extremely rare and expensive vintages being sold at private auctions to unwitting collectors. Bizarrely, sometimes wine fraud happens on supermarket shelves with bottles that retail for less than $10 each.

In one strange case in 2021, a customer at a supermarket in Birmingham, England, noticed that three out of the six bottles of Yellow Tail wine he had purchased looked and tasted extremely different than the other three. This incident wasn't isolated to just one supermarket. According to a member of Birmingham City Council's Trading Standards team quoted in a report by Food & Wine, it's believed that this is happening all over the U.K., and that an organized crime ring may be behind it. While some customers are being fooled, it's unlikely that the local supermarkets selling the counterfeits are. According to a member of the Midlands Police Department, these bottles are not being sold through legitimate distributors, meaning that the individuals in charge of buying stock for the supermarkets have to be aware of the scam. The supermarket in Birmingham that sold the bottles of fake Yellow Tail lost its license to sell alcohol as a result of the incident.

Medieval corrupt wine

Wine fraud has existed in various forms for centuries, and was apparently such an issue in medieval Europe that there were special punishments on the books for anyone found to be presenting cheap wines as valuable ones, and legislation in place to try to make it more difficult to do so.

Throughout history, certain regions have been known for their wines, and some have been considered better than others, leading to the common type of wine fraud where a seller claims that the wine originated in a more prestigious area than it actually did. As described in "The Oxford Companion to Wine," this was such a problem in medieval London that it was actually illegal for taverns to store wines from Germany in the same cellar as ones from France and Spain. It was believed that by keeping them completely separate, it would be more difficult for dishonest tavern keepers to secretly mix more valuable wine with less valuable wine. Wines that were mixed together or diluted were known as "corrupt wine" because they had been corrupted by a cheaper-quality product, and selling corrupt wine was a serious crime. Anyone found selling corrupt wine was forced to drink it and then forbidden from ever selling wine again. While this punishment might seem brutal, it was actually more lenient than in some other places in medieval Europe. In Germany, for instance, those committing wine fraud might be beaten, branded, or even executed.

Fake Bordeaux scandal exposed in 2022

In 2013, a particularly bad harvest threatened to prevent the wine wholesaler Celliers Vinicoles du Blayais from fulfilling its orders. To make up for the considerable difference between the amount of French Bordeaux needed and the amount it actually had to sell, a representative for the company came up with a scheme to trick its buyers into accepting cheap Spanish wines instead. What was supposed to be an illegal stopgap transformed into a multi-million dollar fraud that lasted for years.

The plan was simple: A wine merchant would buy the Spanish wines and then sell them to a merchant in Bordeaux. That merchant would then doctor the records to make it seem as if it were French wine. These were then passed on to Celliers Vinicoles du Blayais, which marketed the fakes as a variety of products ranging from relatively inexpensive French wines to valuable Bordeaux. Investigators believe there may have been millions of bottles of Spanish wine sold as products of France. Two perpetrators were sentenced to house arrest in 2023, while three accomplices were heavily fined.

Windsor Jones

The most well-known form of wine fraud involves passing off a cheaper wine as a more expensive one, but in some cases, con artists are able to trick their targets into paying for wine that they've never even seen. In some cases, the wine that the seller promised never even existed.

For five years, unwary elderly Americans picked up the phone to find charming salesmen with British accents calling to sell them rare wines and whiskeys. These representatives claimed to be working for three companies, Charles Winn, Vintage Whisky Casks, and Windsor Jones. They also claimed they would use investors' money to purchase highly valuable wines, store them safely, and then sell them at a considerable profit, promising their victims a return of more than 30% on their "investments." This was a scam. The money was never used to purchase wine at all, and went into the pockets of the scammers. According to a report by NBC, it is believed that they swindled victims out of more than $13 million.

When one man discovered that his 89-year-old father had paid more than $300,000 and never seen any return on his investments, he went to the police. Soon, the man behind Windsor Jones was put on trial and hundreds of thousands of dollars in transfers were stopped — though only a small percentage of the total amount stolen was able to be returned to the victims.

Brunellogate

Brunello di Montalcino is a kind of Tuscan wine produced only in vineyards in one specific region of Italy and made entirely from acidic sangiovese grapes. However, some began to suspect that many of the bottles of brunello di Montalcino on the market were not actually being made exclusively from sangiovese grapes. Authorities impounded 6.7 million liters of suspicious wines and determined that 20% of them had been diluted with other wines.

Unlike the most common reason for wine fraud — a desire to sell cheap wine for the price of expensive wine — the purported motive in the brunello di Montalcino case was simply flavor. As described by wine expert Franco Ziliani in an interview with The New York Times, Americans are some of the primary consumers of expensive wines, and it's believed that the brunello di Montalcino was being cut with popular wines like cabernet or merlot in order to make the acidic wine more appealing to Americans.

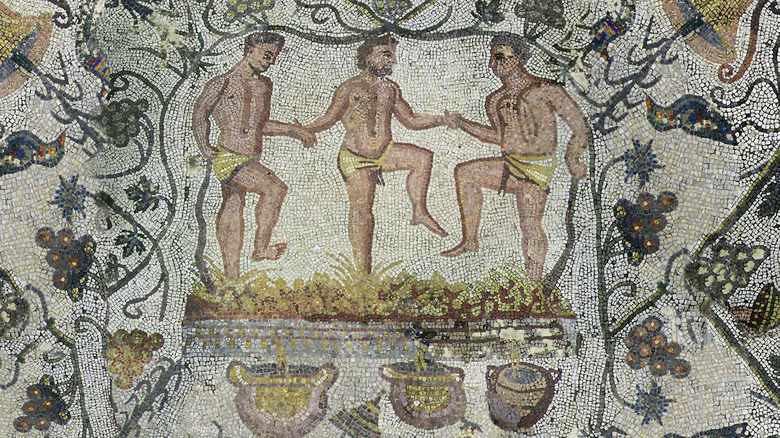

Ancient Roman wine

Wine was extremely important in ancient Rome, and the kind of wine that a person drank said a lot about their social class. As described by archeologist Mario Indelicato in an interview with The Guardian, ancient Roman wine was typically very sour, and the version that was made for lower classes, particularly those who were enslaved, was even more vinegary. Even the higher quality wine for nobles had some of this pungent flavor, so they would usually drink it diluted with water and sweetened with honey. There could have been another difference between the wine that was drunk by the poor and the wine that was drunk by the rich: fraud.

In the first century, it could be extremely difficult to find genuine wines for sale. Surprisingly, it was even harder for people who had the ability to pay high prices for their wine. Wine fraud was extremely prevalent throughout the Roman Empire, with many merchants selling wine that had been diluted. But as described by Pliny the Elder (via Loeb Classics), expensive wines enjoyed by the nobility were far more likely to be cut with other things than the vinegary, cheap wine for the lower classes. It wasn't just an issue of taste and value either — some of the things that were used to cut the wine could be dangerous, leading Pliny to complain that "many poisons are employed to force wine to suit our taste."

Selling the empties

When trying to detect a fake, many focus on verifying that the label and bottle are correct for the vintage — but this method doesn't work for one of the most common forms of wine fraud. In some cases, the valuable bottle purchased may be completely genuine, but the wine inside has been replaced with a cheaper wine. This has created a black-market demand for empty bottles.

After an expensive vintage has been drunk, some empty bottles can be sold for around 25% of the price of the actual wine. That bottle is then filled with a cheaper wine and resold as genuine. Websites and even some seemingly legitimate wine cellars have sprung up to sell undamaged empty bottles from prestigious wines. This issue has become so prevalent in mainland China and Hong Kong that it has become standard practice for venues to publicly shatter the bottles after wine tastings to prove that they won't be resold to make counterfeit wines after the event.

Prohibition-era workarounds

From 1920 to 1933, alcohol was banned in the United States. As described by Karen MacNeil's "The Wine Bible," during Prohibition, wineries were only allowed to make wine for religious or medical purposes. Americans didn't stop drinking wine during the time that alcohol was illegal, however, and a booming black market arose to meet the demands. Sometimes offenders were scamming the customers, sometimes they were deceiving the U.S. government, and sometimes they were tricking both.

During Prohibition, rather than fooling people into thinking they were getting a higher quality of wine than they were, the focus was on making it seem to the authorities like they weren't selling wine at all. One of the most popular methods was creating solid bricks of non-alcoholic grape concentrate and selling them to consumers with a strongly tongue-in-cheek warning not to dissolve the brick in water and leave it to ferment, or they would be breaking the law.

A lot of the fake wines being sold were not as safe as wine bricks. Because it was an illegal product, consumers had less options for where they could buy and still had to pay high prices, which left a lot of room for sellers to defraud their buyers. One of the most commonly sold options was actually denatured alcohol that had been redistilled and dyed.

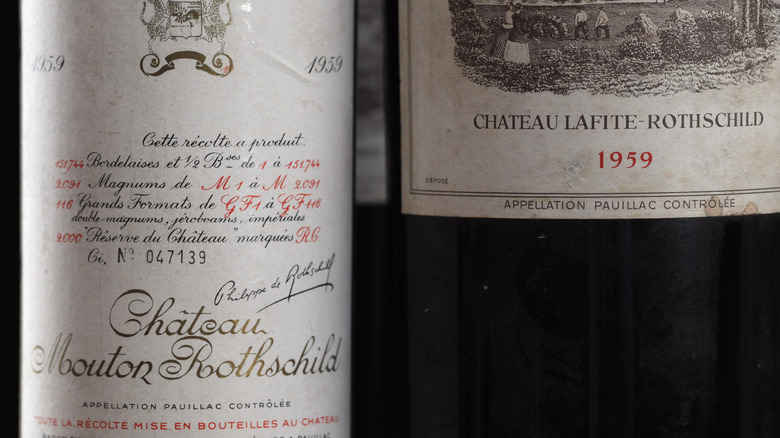

Jefferson bottles

One of the most bizarre stories of counterfeit wine occurred in the 1980s, when German pop band manager Hardy Rodenstock claimed that he had been sold a secret stash of wine owned by America's third president. As described by the New Yorker, Rodenstock was known for holding lavish wine tastings during which the guests were required to drink the wines rather than spit them out. At the end of the event, the most expensive vintages would come out — but by that time the guests were likely too inebriated to truly evaluate them. Then, in 1985, he claimed that he had been contacted by someone who had discovered a secret Parisian stash of wines that had belonged to Thomas Jefferson. They were sold for large sums at auction, but when one of these wines was tested, it was determined that the bottles actually contained a mix of several wines, half of which were from the 1960s or later.

Although the Jefferson bottles received the most attention, Rodenstock also claimed to have wines that were owned by several other famous historical figures, including Czar Nicholas II.

Tens of thousands of fake labels

One of the ways in which fraudsters transform a cheap wine into an expensive one is by changing the label. When making a counterfeit of an older vintage, scammers have to artificially age the paper of the labels to make them more convincing. When recreating more modern labels, counterfeiters simply have to copy the labels as accurately as possible. In 2014, it was reported that there were tens of thousands of bottles of Italian wines on the market with the wrong labels. The labels were forgeries of those of several prestigious red wines, which retail for around the equivalent of $150. Inside, the bottles contained wines worth less than $2.

As reported by The Telegraph, authorities in Italy investigated restaurants, bars, and supermarkets, taking more than 30,000 bottles on suspicion that they were counterfeits. It's believed that the scam artists made millions on their fraud. The cost to the wineries whose prestigious reds were counterfeited may have been even greater. It's estimated that wineries in Tuscany lost hundreds of thousands of dollars in sales, but the damage to their reputations may be more severe.

Jesus units

Diluting wine is an extremely common form of wine fraud, but whether or not adding water to wine is always fraudulent is a very controversial issue in the modern wine industry. In many situations, it's illegal to add water to wine, but according to British wine critic Jancis Robinson, in some situations, adding water to wine actually improves the taste. Because of the way that modern wine grapes are grown, higher sugar levels paired with stronger yeast can lead to higher alcohol levels than wine typically has. In many situations this isn't just unpalatable, it's illegal. For example, it can be illegal to import wines over 15% alcohol into Europe. The easiest way to bring down the percentage is to add a carefully calculated amount of water to the wine. This strategy is so controversial that many in the wine industry use a euphemism for the amount of water needed for the wine: "Jesus units."