How T.S. Eliot Finally Quit His Day Job To Become A Famous Poet

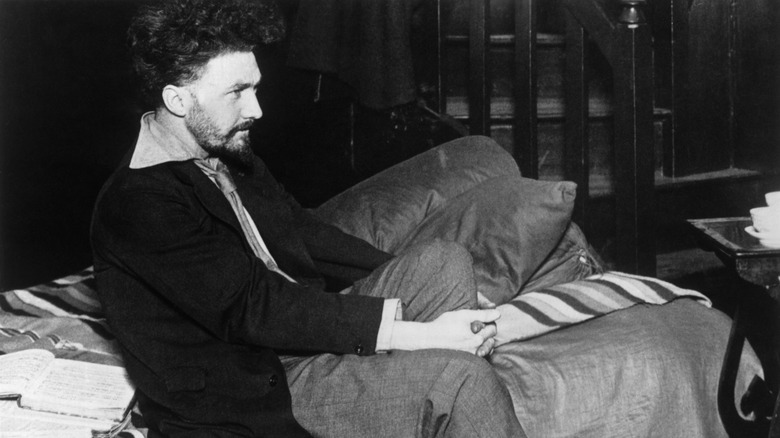

In 1948, the British-American poet Thomas Sterns Eliot – known by the pen name T.S. Eliot — was awarded the most coveted award in the world of letters: the Nobel Prize in Literature. Though Eliot had come from a wealthy family and proven to be a talented academic who attended both Harvard University and the University of Oxford in the U.K., his path to literary glory was a difficult one.

Having overcome a childhood plagued by ill health – during which time he sought solace in the world of books, especially detective stories including the works of Sherlock Holmes creator Arthur Conan Doyle, according to Robert Crawford's "Young Eliot" – the future Nobel laureate became obsessed by language and poetry, and by his early 20s he was writing some of the most cutting edge poetry of the modernist movement while holding down various day jobs.

Thankfully, Eliot's innate poetic talents soon drew the attention of some of the most prominent modernists of the age. But it was the poet Ezra Pound — three years Eliot's senior and one of the defining voices of early 20th-century modernism — who changed Eliot's life forever, ensuring that the young poet attracted an appreciative audience and became ensconced in Europe's literary scene. As well as that, he made steps to ensure that Eliot made the most of his abilities, concocting a scheme in the 1940s by which he believed he could liberate Eliot — who at that time worked full-time as a clerk in Lloyd's Bank in London — from the necessity of working a day job to make ends meet.

Ezra Pound's mentorship

Along with the hugely influential Gertrude Stein – who mentored several of Paris' greatest ex-pat American writers during the 1920s, including Ernest Hemingway and F. Scott Fitzgerald — Ezra Pound was one of the modernist movement's kingmakers: a figure whose opinion of the writers and artists he encountered meant more in his day that the work he himself created.

Pound knew what he liked, and he saw enormous potential in the young T.S. Eliot, to whose work he was introduced by the writer Conrad Aiken, per The Paris Review. Pound was so excited by what he read of Eliot's poetry that he forwarded copies to a friend, writing: "I enclose a poem by the last intelligent man I've found — a young American, T. S. Eliot ... I think him worth watching" (via "An Imperfect Life"). Pound later became instrumental in the creation of Eliot's "The Waste Land," acting as editor and helping to achieve the fragmentary effect for which it is famous.

But while Eliot had made a splash in the literary world with his early poems such as "The Lovesong of J. Alfred Prufrock" — which Pound had pushed to have published in the magazine "Poetry" – and later established himself as a boundary-pushing modernist with his most famous work, after dropping out of a doctorate and a brief spell as a lecturer, Eliot came to spend the majority of his daylight hours working as Lloyd's bank, drawing a normal paycheck to support himself and his wife, who was chronically ill. But for Pound, this was an unacceptable waste of a great poet's time.

A financial investment in talent

To help T.S. Eliot make more time for writing, Ezra Pound advertised a trust fund, the "Bel Esprit," inviting 30 members of the 1920s literary scene to invest to give him a yearly stipend worth a modest salary making him less dependent on wage-earning non-poetic work. Many signed up to support the well-thought-of poet, believing they were taking steps to liberate him from his desk job and free him to pursue his great poetic vocation. Indeed, by 1921, the strain of his growing stature as a poet, increased pressure in his banking job, and the mental illness of Eliot's wife at the time led to him having a mental breakdown, for which he required psychotherapy.

According to "An Imperfect Life," Pound transferred the Eliots just under half of the funds he had acquired, with the elder modernist seemingly successful in drumming up financial backing for the writer of "The Waste Land."

But money itself seemingly wasn't the issue. Though the patronage given to him by his fellow poets was generous, Eliot was already making far more in poetry awards, such as the thousands he had received as the winner of the Dial magazine poetry prize. He also made an income from shares he had inherited from his father, meaning he would likely have been able to afford to leave the job if he wanted to. So why didn't he?

E.S. Eliot: poet and editor

Though Eliot did reportedly accept some money from Pound's fund, he remained in his position at the bank, where he had prospects and security at Lloyd's which meant a more reliable income for Eliot's wife if anything were to happen to him — indeed she wrote to friends explaining that she would be upset if he were to quit.

Plus, Eliot argued the role interfered with his poetic work little, and even if enough rich patrons had allowed Eliot to, as it were, reserve his office hours for the writing of poetry, it seems that he would have been hesitant to arrange his life in such a fashion. As Eliot told The Paris Review in his "The Art of Poetry" interview, he tended to compose poetry for a maximum of three hours a day, finding that he often had to turn his mind to "something else" to get his creative juices flowing in that small window. "I feel quite sure that if I'd started by having independent means, if I hadn't had to bother about earning a living and could have given all my time to poetry, it would have had a deadening influence on me," Eliot added.

Though Eliot didn't quite take the full patronage of the Bel Esprit as Pound had hoped, he did eventually leave Lloyd's bank to take up another full-time position as an editor at the newly formed Faber & Gwyer publishing house, which also published his poetry. Eliot's new role allowed him to remain adjacent to the world of literature and keep an eye on the new poetry that emerged in his wake.