From Migrant Worker To Astronaut: The True Story Of Jose Hernandez

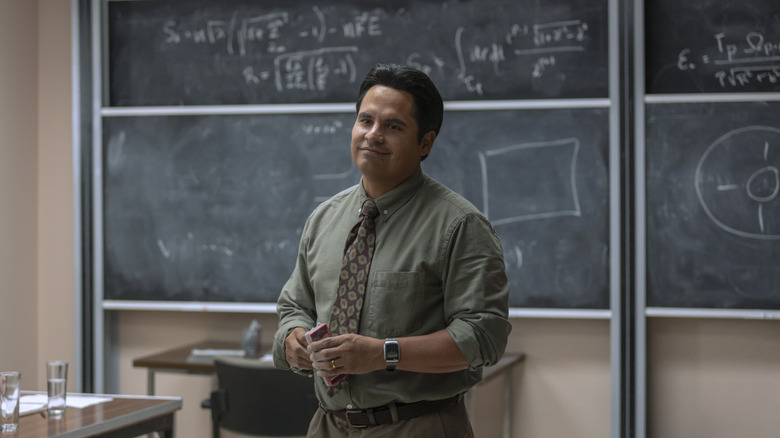

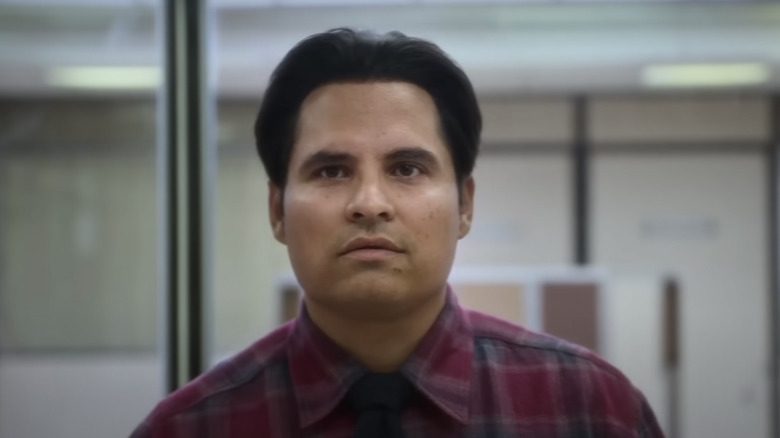

José Hernández is the subject of Amazon Prime Video's biopic, "A Million Miles Away." Based on Hernández's memoir, "Reaching for the Stars: The Inspiring Story of a Migrant Farmworker Turned Astronaut" and starring Michael Peña, it tells his inspiring story. "A Million Miles Away" is faithful to Hernández's autobiography; with its two-hour runtime, it recreates most of the key moments in his life from childhood to blastoff. But there isn't enough time or space to do all of his accomplishments justice, and the wholly real story is even more incredible than the made-for-streaming version.

Compared to the movie, Hernández's memoir is more specific and unflinching about his origin. Born a first-generation Mexican American in California to undocumented immigrant parents, he had a difficult but hopeful start to life. His father, Salvador, left rural Michoacán, Mexico as a young man because of lack of opportunity. He'd return to marry Hernández's mother, Julia, and the couple grew their large family (Hernández is one of four children) and their small fortune as they lived on the road and picked crops according to a well-trodden seasonal rotation. From there, thanks to his own talent and determination plus the support he received along the way, Hernández would go on to achieve things that would far exceed most parents' dreams for their kids. But to him and his parents, they were distant though attainable goals. This is how Hernández turned those dreams into a reality.

The family's lifestyle made education a challenge

In the brief opening segments of "A Million Miles Away," we see how the Hernández family's nomadic lifestyle affected their children's education. The migrant work that took them up and down California and back to Mexico every year meant switching school districts and missing class. That the elementary-aged kids were putting in shifts of physical labor whenever possible also made it tough to stay awake and concentrate during their lessons. In an interview with the U.S. State Department, José Hernández explained that he and his siblings moved between three or four different districts a year and went without formal schooling for three or four months whenever they'd return home to Michoacán. Ironically, his passion for engineering sprang from their grueling schedule. "My refuge was math," he said, "because one plus one was two in any language."

Still, that much disruption stalled the learning process for the children, particularly when it came to understanding and speaking English with much fluency. Hernández — who wasn't proficient until he was 12 — remembers in his memoir that his father insisted they learn if they were going to live and work in the United States. So, not only did the kids have to toil in the fields and go to school, they had to study during their almost non-existent free time just to keep up with the other students. Any remaining spare time, a young Hernández spent watching "Star Trek" or gazing up at the sky.

A second grade teacher changed his life

Salvadore Hernández's decision to work as a migrant in the United States was, in a way, José Hernández's first lucky break. His second came when a teacher intervened to provide him with the stability he needed to thrive. Screenwriter Márquez Abella told TODAY that, as depicted in "A Million Miles Away," Hernández's second grade teacher, Miss Young, really did change his life. Until that point, the family had followed the harvest but called Stockton, California their home away from home. The parents took Miss Young's advice to stay put, and the children were permanently enrolled in school in Stockton.

The movie does take some very minor liberties with Miss Young's serendipitous presence. Hernández told the GDA Podcast that his second grade year marked the fourth and not the first time Miss Young paid them a visit. Sal Hernández would ask teachers to prepare schoolwork for his children while the family was in Mexico, which they would complete under the supervision of their grandmother at the kitchen table. Each time Miss Young had one of the Hernández siblings, she made her stance known. She saw potential in youngest child José, who said, "I guess the fourth time was the charm."

Additionally, in the film, Hernández's family surprises him by bringing Miss Young to see him before he leaves for space. In reality, Hernández had the school district look into her whereabouts and saved a seat for her at the launch.

He participated in the Upward Bound program

José Hernández would go on to graduate from Stockton's Franklin High School and, once he made a name for himself, would come to claim the city as his hometown (via VisitStockton.com). Stockton takes great pride in claiming him as well. But the local kid who went from the fields to outer space has a federal after-school program facilitated by Franklin High to thank for giving him the extra lift-off that helped him attain his goal. During his high school years, Hernández was a participant in the Upward Bound TRIO program, which helps qualifying students to become college-ready and prepare for the application process. Because Hernández's family was low-income and because neither of his parents had been to university, he — a promising math and science prospect — was an ideal candidate.

"Upward Bound was instrumental in pursuing my dreams," Hernández told the audience at the Lyndon Baines Johnson Distinguished Lecturer Series. "They exposed me to STEM. They made me lose fear in it and helped me embrace it." The now-retired astronaut has a display dedicated to him at the Children's Museum of Stockton and he regularly makes appearances at Upward Bound events. His lived experience is a motivating example for the next generation of underprivileged high achievers.

His father gave him a recipe for success

Whenever José Hernández tells his story in print or in person, he's sure to include his father's recipe for success. Salvadore Hernández was such an influence on his son, the astronaut's memoir begins with his father's life and not his own. And that five-part recipe is so important to the film's subject, it became the framework for "A Million Miles Away" after the fact, according to screenwriter Márquez Abella (via TODAY).

Like José, Salvadore spent his early childhood attending school and doing farm work and like José, Salvadore had a passion for education and a drive to succeed. However, his formal schooling ended in third grade, around the same point when his son's was finally beginning in earnest. Settling in Stockton meant José would have opportunities that Salvadore simply didn't, but he did know how to help his son make the most of them. His recipe was really a way of being optimistic yet practical. He taught José to identify his goal, figure out how far away he was from meeting it, and map a path to get there. What he didn't know, he'd have to learn, and once he finally reached his goal, he'd have to be ready for the real work to begin.

The recipe also inadvertently taught José to enjoy the journey to the destination, which he told the San Francisco Chronicle's Datebook, accounts for most of his life story.

His work improved early detection of breast cancer

José Hernández's post-high school journey began with a bachelor's degree in electrical engineering from the University of the Pacific, continued with a master's degree from the University of California Santa Barbara, and picked up steam when he landed a job at the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory in (via NASA). In "A Million Miles Away," Hernández is mistaken for a janitor when he shows up at work. That happened; Hernández told The News-Herald, "There were two of us that started in that building the same day. One was José Hernández, and another one was a 'Steve Smith,' for lack of a better name. And, of course, they knew one was a janitor and one was an engineer, so they assumed José Hernández must be the janitor."

Hernández stayed at Lawrence Livermore from 1987 to 2001, during which time he was involved primarily with medical imaging and Russian diplomacy. What the film doesn't get into is what the would-be astronaut has called the proudest moment of his professional career (via Datebook). "I was one of two people who codeveloped the first full-field digital mammography system," he explained. This innovation made clearer test results and earlier detection of breast cancer possible, which has in turn saved hundreds of thousands of lives by Hernández's estimation.

Nasa rejected him 11 times

It isn't just the metaphorical distance, from migrant worker to astronaut, that José Hernández had to travel to make his dream come true; it's the persistence with which he pursued that dream that makes his story so unique yet relatable. Famously (and as is illustrated in the film), Hernández was rejected by NASA 11 times (via The Californian). Rather than give in to his disappointment and quit, Hernández — propelled by his work ethic, his father's recipe, and his wife Adela's support — used each rejection as a chance to improve himself as a candidate.

"I started to look at the skills that the selected astronauts had," he said. He realized that, while he'd received a comparable education and had relevant work experience, he didn't possess some of the valuable and highly specialized abilities that were practically required of the recruits. Hernández received his pilot's license, became a certified scuba diver, and learned Russian. "I didn't get frustrated," he said. "If I made it, great. If not, it was not going to be the end of the world because I loved what I was doing." That philosophy, which Hernández describes as dreaming big while putting in the work, helped him get his foot in the door at NASA.

On the 12th try, he achieved his goal

In 2001, José Hernández left Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory for NASA... but not as an astronaut. Hernández joined the team at Johnson Space Center in Houston, Texas, where he worked in the materials and processes department. He was finally accepted into the Astronaut Candidate program three years later, in 2004. Even so, his dream wasn't a foregone conclusion. From 2004 to 2006, Hernández underwent rigorous scientific study and survival training sessions during which he was pushed to his limits mentally and physically. Just as his father had warned him about in the fifth step of his recipe, the real challenge began once he'd reached his goal.

Eventually, he was assigned to Florida's Kennedy Space Center where he helped prepare for shuttle launches and landings. Then, in 2009, he got the chance to do the very thing he'd been imagining ever since he was a kid watching the Apollo 17 mission on his family's antennae TV (via Visit Stockton). Hernández received an offer to be a mission specialist on STS-128, a 14-day trip into outer space. From August 28 to September 11 of that year, on the 128th shuttle mission and the 30th to the International Space Station, Hernández logged 217 orbits of the Earth over 5.7 million miles. "You go from zero to 17,500 miles an hour in eight and a half minutes," Hernández told PEOPLE, comparing it to an amusement park ride. It's an experience that only about 500 people out of 7 billion have ever had, and it's one that he found humbling.

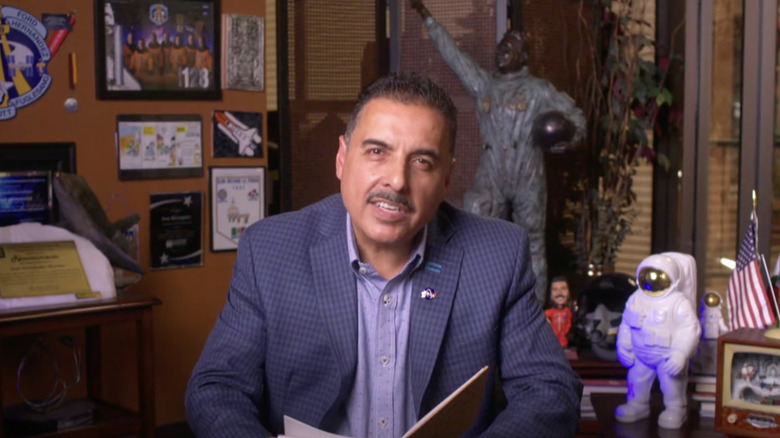

He continued to reach for the stars after his retirement

After having fulfilled his personal mission, astronaut José Hernández retired from NASA in January 2011. But, as one might expect of someone as hard-working, focused, and ambitious as Hernández, retirement didn't mean he stopped being productive. Shortly after this time with the space program concluded, Hernández founded Tierra Luna Engineering (via GDA Speakers), a private company that allowed him to combine his interests in STEM, entrepreneurism, and public service. That same year, he penned his aforementioned memoir, "Reaching for the Stars: The Inspiring Story of a Migrant Farmworker Turned Astronaut," which was published by Center Street, a subsidiary of Hachette Book Group. The book would become the basis of the Amazon Studios film, "A Million Miles Away," which premiered on the streaming service on September 15, 2023.

While he was writing and consulting, Hernández was also making the rounds as a motivational speaker. Today, he continues to share his life story and his perspective on issues ranging from the immigrant experience to dealing with imposter syndrome to the importance of teamwork (and, of course, science and space). He's been featured on multiple local and national news outlets and appeared on "The Oprah Winfrey Show." Hernández thanks Winfrey in the author's note of his book. It was the talk show host who suggested this next phase in Hernández's career upon interviewing him.

He ran for office... but lost

Even the most capable and dedicated individuals can't do everything they set their minds to, and José Hernández is proof. In 2012 (the same year he founded his company and wrote his memoir), Hernández mounted a campaign to represent California's 10th House District. He ran as a Democrat and won his primary on a platform of immigration reform, advocacy for NASA, and attention to the problems that were plaguing his community, such as the housing crisis. Politics is often a natural next step for astronauts. Five have been elected to Congress including John Glenn and Mark Kelly. But a tough general election turned out to be one of the very few fights Hernández couldn't win.

For one thing, he was the challenger running against an incumbent, Republican Jeff Dunham, who also happened to be a fellow farmer and a veteran. Hernández's stance on immigration was also less popular with the public at large than it was within the Democratic Party. The son of undocumented migrant workers favored policies that made it easier for people like his parents to get American citizenship. It didn't help that the Republican party sought to keep Hernández from using the word astronaut and NASA-like imagery in his campaign materials and on the ballot. A judge ruled in Hernández's favor, but in the end, he lost the race to Dunham, garnering 46.2% of the total vote.

He went back to the fields after retirement

The name of José Hernández's aerospace consulting company, Tierra Luna, means Earth and moon. In some ways, the path Hernández's life took looks like a sharply rising trajectory toward the stars. In other ways, his story has come full circle. Hernández and his family are just as connected to the land now as they were generations ago, and they've repeatedly used those words — Tierra Luna — to mark their many business ventures as their own. Adela Hernández achieved her own dream of opening up a restaurant while her husband was employed by NASA (via the Stockton Record). The Tierra Luna Grill was open for about five years, and the couple's five children helped their mother with the daily operations.

The Earth and moon are also the inspiration behind the name of the winery that José and his father, Salvadore, founded in their adopted hometown of Stockton, California (via the Stockton Chamber of Commerce). Tierra Luna Cellars produces varieties and blends of wine that José names after the constellations. He also donates a portion of the proceeds to STEM-related causes. Though they're back in the fields harvesting grapes, this time, the Hernández family is doing it on their own terms, with all of their astronomically big goals, having been reached, in the rear view mirror of a space shuttle.