The Secret Service Code Names For JFK And His Family

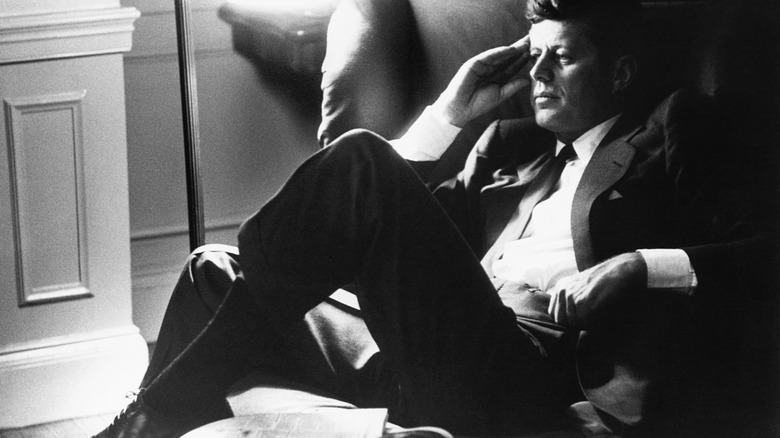

The Camelot mythology is tightly intertwined with John F. Kennedy. The Arthurian mystique can be read into when discussing all areas of the Kennedy White House. A first glance at the code names used by the Secret Service for his administration (preserved by the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum) might even lead some to wonder if the president's bodyguards had Camelot in mind. The Secret Service designated the White House as "Crown" and Kennedy as "Lancer" — a term not wildly off from Lancelot, and traditional lancers were mounted warriors just as knights were. His children, Caroline and John Jr., were labeled "Lyric" and "Lark," respectively, designations with vaguely medieval associations. Jaqueline Kennedy was known as "Lace," and isn't that associated with costumes of the Middle Ages?

If that last one seems like a reach, it's because it is. All associations between Camelot and the Kennedy code names are coincidences. Kennedy was only tied to Camelot after his presidency — and his life — came to an end. Specifically, Jaqueline made the comparison while memorializing her murdered husband in 1963, kickstarting a mythology that has been alternatively embraced and bemoaned, per The Daily Beast. A look through the full list should betray that the Secret Service didn't have Camelot in mind when labeling the administration (good luck fitting Agent Gerald Behn's code name of "Duplex" into Arthurian lore).

Presidents help pick their code names

The Secret Service might not have themed their code names for the John F. Kennedy administration on Arthurian lore, but that doesn't mean the names were entirely random — or that Kennedy wouldn't have had a hand in his own name. Secret Service code names go back to Harry Truman's time in office. American historian Michael Beschloss told NPR those who come under the agency's protection are given a list of possible code names, and the protectee can pick whichever one they like. Over the years, it's become a tradition to have the first family choose alliterative code names based on the first letter of the president's choice — hence the "L" names among the Kennedys taking after Lancer. And the designations aren't fixed once chosen. George W. Bush was known as "Tumbler" during his father's administration but opted for "Trailblazer" once he won the White House in his own right (per Vanity Fair).

Presidents may opt for a code name that resonates with them in some way. Historian Michael Beschloss suggested to NPR that Truman's code name, "General," was a bit of wish fulfillment on the once-captain's part. But according to the Chicago Tribune, a White House Communications Agency claimed the initial lists are arbitrary, and NBC New York reported that presidents typically don't publicly explain why they went with this or that moniker. Kennedy left no record on why he went with Lancer, though everyone from Vanity Fair to Britannica has suggested it has Arthurian meaning.

Code names are a matter of tradition, not security

In John F. Kennedy's day, his Secret Service code name wouldn't have been in the public record, as it still would have had security purposes. Per Nexstar Media Wire (via RochesterFirst.com), the code names first came about in the days before encrypted communications. Lest unfriendly ears listen in on conversations regarding the president, his family, or their movements, code names let the Secret Service more safely discuss those under their protection. But with the advent of more secure — and more varied — channels of communication, code names were no longer essential and became more a matter of tradition.

There is still some practical value to the code names. Using them can make for effective shorthand in communications between Secret Service agents, which is why they tend to be two or three syllables and clearly recognizable words or names. The best code names are also those that won't cause confusion, as Happy Rockefeller's initial moniker did. As wife of Vice President Nelson Rockefeller under the Gerald Ford administration, she initially went by "Shooting Star," but the problems of mentioning "shooting" in messages and conversations among security quickly became apparent. She was rechristened "Stardust."