The Untold Truth Of Bayard Rustin

Biopics tend to be made about the most famous figures from history. Malcolm X and Muhammed Ali, for example, have both had their lives adapted for the big screen, in the unsurprisingly named 1992 and 2001 films "Malcolm X" and "Ali." Even when a historically-based movie — like 2020's "One Night in Miami" — seeks to highlight an important moment from the past rather than a single person, the narrative often focuses on the most notable people ... in that case, Malcolm X and who was then Cassius Clay. Netflix's upcoming biopic, "Rustin" (which is also largely set in the 1960s and about the civil rights movement), takes the opposite approach. It puts Bayard Rustin at the center of the frame when, in real life, he was purposefully relegated to the margins by his friends and his enemies alike.

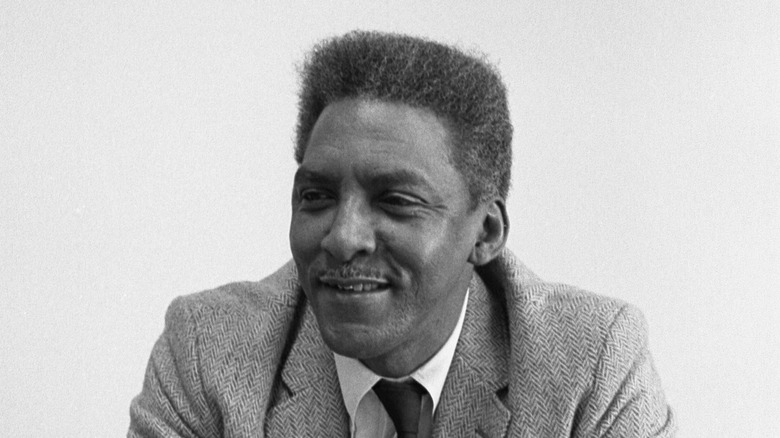

Rustin was a monumentally important, inspirational, and organizational force behind several of the social movements of the 20th century. Yet, until recently, much of the public (including people with vested interests in his work) had never heard of him. That's because, as an outwardly gay Black man with communist associations and a lengthy criminal record, Rustin wasn't an ideal poster boy for any of the causes he championed. He struggled without recognition for decades, during which time he won major symbolic and practical victories for people of color, queer people, labor unions, and the incarcerated. Now, nearly 50 years after his death, he'll become the Civil Rights icon he should've been, thanks to the reach of Netflix. The full story of Rustin's 75-year life, however, is even more fascinating than the made-for-streaming 100-minute version.

He thought his mother was his sister

Bayard Rustin's life was full of intrigue from the very moment of his birth on March 17, 1912. Rustin grew up in West Chester, Pennsylvania, in a family with eight other children, all of whom were older than him. His mother and father (or so he thought) were Janifer and Julia Rustin. Janifer was born as an enslaved person but went on to work for the Elks Lodge. Julia's family had worked in domestic service for a well-established and well-respected Quaker family; they paid for her schooling and she became a nurse, as well as a founding member of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. The couple married and built a happy, middle-class life for themselves. They named their ninth child, Bayard Rustin, after local writer, Bayard Taylor, and raised him with the Quaker beliefs of nonviolent conflict resolution and selfless civil service.

But, as Rustin himself explained in an interview with Peg Byron of The Washington Blade (made available by his partner, Walter Naegle, via the Making Gay History podcast), his family wasn't exactly what it appeared to be. "I was born illegitimately to my mother when she was 16 and my father was 17," he told Byron. Janifer and Julia's oldest daughter, Florence, was impregnated by a man named Archie Hopkins, who drank, gambled, and was unfaithful ... habits which did not align with their beliefs or lifestyle. The Rustins didn't want to tie Florence down to such a character with a marriage, so they brought up Rustin as their own. "I must have been nine or 10 before I realized my mother was not my sister," he said.

He realized he was gay in high school

Like many members of the queer community, Bayard Rustin began to better understand his identity and sexuality during his teenage years. "I recognized that I was gay when I was in high school," he recounted to the Washington Blade. "I knew then that my affection was far more for men than women." He was a student at the relatively affluent and integrated West Chester High School at the time, and a popular one at that. Rustin may have been aware of his sexual preferences, but he hadn't come out yet, and he felt lucky that he'd been able to pass for straight because of that popularity and his athletic prowess. "I was on the championship football team. I was on the championship track team. I won the all-state high school championship for tennis," he explained, adding that he received an honorary fourth letter for managing the boys basketball team.

Coincidentally, it was sports that lit the spark that led to Rustin's activism. When the banquet to celebrate the championship football team was held at the YMCA, his grandmother supported him in boycotting the event because the facility was still segregated; its pool was off-limits to Black people. Though the issue in question was his race, he credits that moment with preparing him to face bigotry about his homosexuality. Rustin came out in college, but only to those in his social circles.

His grandmother was an ally

Bayard Rustin was fortunate to have his grandmother, Julia, whom he describes as a "marvelous person" (via The Washington Blade). Not only did she handle the circumstances of his birth with love and open-mindedness, but she also instilled in him the values that would drive his activism. Perhaps most importantly, she accepted his sexuality and sometimes even gave him sound advice about navigating the world as a gay Black man, even though she never used those words.

Rustin described how Julia would encourage him to invite his significant others home to visit. "She would say, 'Oh, that young man that you've been writing to me about from Cleveland sounds very interesting, why don't you bring him?' I think she was saving me from asking to bring him," he said, affecting his grandmother's warm tone. The closest Rustin got to coming out to Julia was to admit that he preferred the company of men to women (via Religion Dispatches), to which she replied, "I suppose that's what you need to do." According to Davis Platt, an early romantic partner of Rustin's, Julia's support allowed her grandson to live and love without shame.

She may have been happy to host her grandson's "college friends," but she wasn't naive about the daunting personal and political reality that he faced as a member of two marginalized groups. Rustin had a promising future ahead of him, and she warned him not to "associate" (as he put it) with people who didn't have as much to lose as he did.

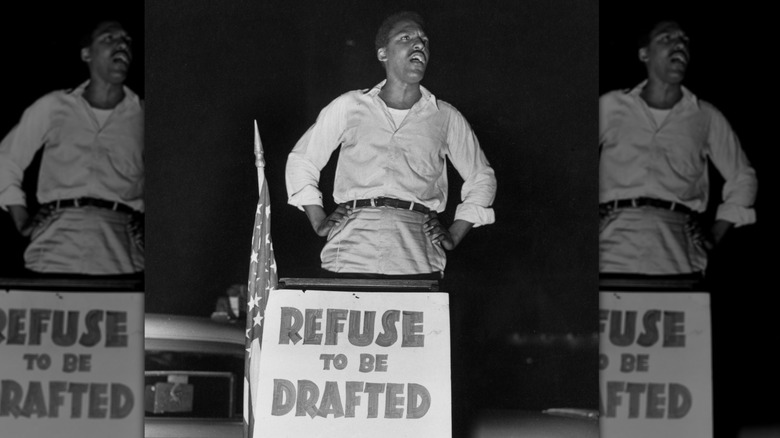

He was a communist and a conscientious objector

In his late 20s and early 30s, Bayard Rustin took some political stances that were highly controversial for the time and would still be considered somewhat extreme by today's standards. Yet his opinions about race, workers' rights, and the prison and military industrial complexes would become foundational to the Civil Rights, labor movement, and anti-war movements that would come to define the latter half of the century.

By 1937, Rustin had already affiliated himself with groups like the American Friends Service Committee, a Quaker organization that espoused social justice and non-violence. A year later, he officially joined the Young Communist League, but he promptly left the party when it shifted its focus from racial equity and changed its pacifist stance on World War II. Committed to nonviolence even during the threat of Nazism, Rustin became a conscientious objector.

Prior to American involvement, he served as a youth organizer in a planned 1941 March on Washington, which was intended to lobby then-president Franklin Delano Roosevelt to enact discrimination protections for Black soldiers and workers in the defense industry. FDR acquiesced, and the March never happened. After Americans joined the war effort, Rustin's refusal to show up for his physical resulted in his arrest. These experiences taught a young adult Rustin how to protest effectively, but the communist and draft-dodger labels would follow him throughout his career.

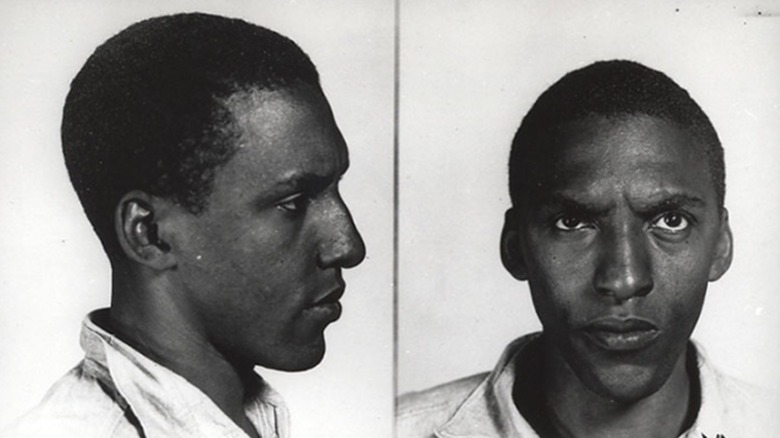

He was arrested ... a lot

After refusing to report for drafted service in 1943, Bayard Rustin was sentenced to three years in federal prison at Lewisburg Penitentiary and served 28 months. It wasn't the first time his conscience conflicted with the law, and it wouldn't be the last. A teenage Rustin used civil disobedience to challenge racial policy at hotels, restaurants, and movie theaters, for which he was arrested at least once. His work with FOR (the Fellowship for Reconciliation) and CORE (the Committee on Racial Equity) meant more demonstrations and arrests. Rustin turned one 22-day stint into a report that led to the end of chain gangs.

Rustin's activism on race informed his perspective on gay rights. He told the Washington Blade about an incident on a bus when a white child's mother used a racial slur. Rustin realized, "I owe it (...) not only to my own dignity, but I owe it to that child that it should be educated to know that Blacks do not want to sit in the back, and therefore I should get arrested." He continued, "it occurred to me shortly after that that it was an absolute necessity for me to declare homosexuality, because if I didn't I was a part of the prejudice ... the prejudice that was a part of the effort to destroy me."

That very prejudice would land him in jail again. In 1953, while in Pasadena, California, for a conference, Rustin was arrested for vagrancy and lewd conduct when he was caught with two men in a car. He was sentenced to two months in jail and made to register as a sex offender.

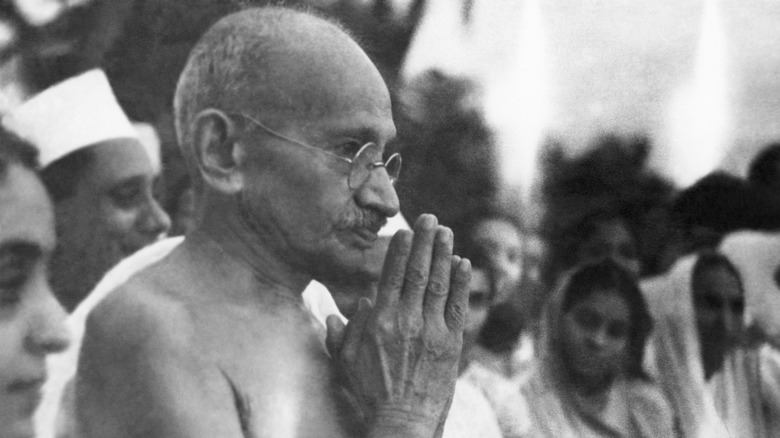

Gandhi was a major influence

Bayard Rustin had been learning and practicing pacifism via osmosis since infancy, thanks to his enlightened mother figure, Julia. He relied upon those convictions and those strategies in his days as a budding political organizer, but he sought out the expertise of a world-famous pacifist when he was beginning to make a name for himself on the national stage. Mahatma Gandhi, the Indian political and thought leader who championed peaceful resistance, invited Rustin to an international forum on the topic, which was to take place in his home country in February of 1949. Gandhi's philosophies — particularly those found in the book "War without Violence: A Study of Gandhi's Method and its Accomplishments" — were appealing to Rustin — a Black, gay Quaker — who needed to find ways to fight the oppression without resorting to actual fighting.

Unfortunately, Gandhi was assassinated in 1948 before he and Rustin could ever meet in person. The conference went on without him, put on by his son, and Rustin still attended. He used the wisdom he gleaned from six months of convening with other pacifists in India to influence the direction of the Civil Rights movement back in the United States. Upon his return, Rustin convinced Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. — who, at the time, owned personal firearms — that he ought to fully commit to Gandhi's brand of nonviolent resistance, not just as a good public relations strategy but as a belief system. Tragically, like Gandhi, King would be assassinated with a gun.

The FBI kept tabs on him

That the FBI had it out for Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. is, by now, fairly common knowledge. But if the bureau saw King as a threat, it most certainly feared his right-hand man Bayard Rustin's influence. King and Rustin met during the Bus Boycott in 1956, and the two men with similar goals but very different skill sets went on to form a close and occasionally contentious working relationship. King became the figurehead of the Civil Rights movement, but Rustin was its chief organizer behind the scenes, doing the grunt work of enlisting volunteers, planning routes, and manning phones.

As it so happened, someone was often listening in on the line. FBI vault records show that Rustin was a surveillance target throughout the 1960s. The organization wasn't just spying on King and Rustin for intel about their political machinations; it was looking for ways to blunt the momentum of the Civil Rights movement by discrediting its key figures. More valuable than recorded statements about, say, fundraising for the March on Washington or stances on the Vietnam War, were salacious details about King's and Rustin's personal lives. On King, the FBI had evidence of infidelity. As for Rustin, now unsealed but still partially redacted files repeatedly refer to him as a communist and homosexual. Rustin told the Washington Blade that, "J. Edgar Hoover began to circulate all kinds of stories about Martin Luther King (...) hinting that somehow or other there might be some homosexual relationship going on between us."

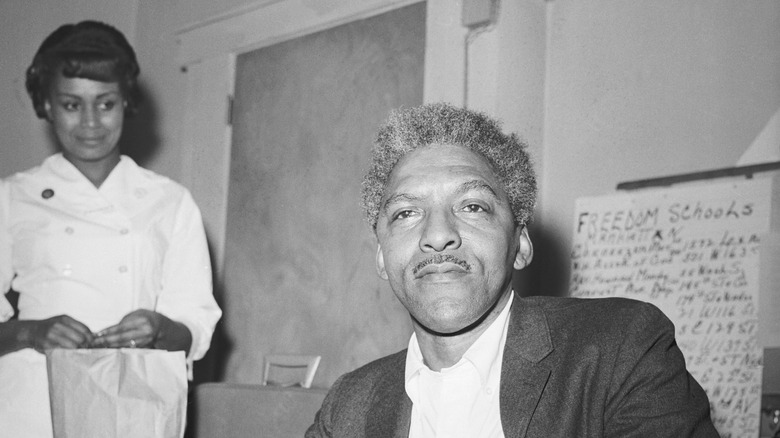

The March on Washington was at risk because of his sexuality

Though the 1963 March on Washington was, in part, the result of Bayard Rustin's vision and tireless work, one of the most iconic protests in history almost didn't happen because of his involvement. In 1962, King, Rustin, and A. Philip Randolph conceived of a march on the Democratic National Convention to press the party to do better by its Black constituents. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. knew that Rustin was gay, and a Black congressman, Adam Clayton Powell, was enlisted to threaten King with false rumors of a romantic relationship between him and Rustin if they didn't call it off. Rustin told the Washington Blade that King formed a committee to determine if his open homosexuality would be a problem or even a danger to the movement. When that committee determined he did pose a risk, he was asked to vacate his position within the Southern Christian Leadership Conference.

A year later, as the March on Washington was being planned with his help, Rustin explained that, "Strom Thurmond (...) attacked me as a draft dodger, which was untrue, because I was a conscientious objector and well known as being a Quaker opposed to all violence. He attacked me as a former member of the Young Communist League, which was true. I had been. He attacked me as a homosexual. Which of course I was." Leadership, including King and Randolph, stood behind Rustin this time, and the March went on as intended. They vouched for his character, as did prominent Catholics, Jews, and union leaders — Rustin had cultivated important relationships supporting their causes over the years.

He adopted his romantic partner

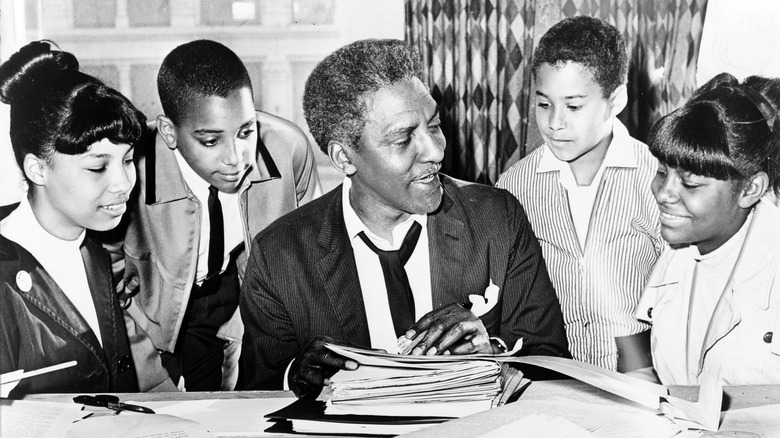

After the March on Washington, Bayard Rustin continued to use his talent for social and political organizing to fight for people and causes that stirred his passions. Rustin advocated on behalf of AIDS victims within the NAACP, and he saw acceptance of the queer community as society's next human rights barometer. He also fought for what was right in his own life as best he could under the circumstances.

Rustin found personal happiness in his golden years with a man named Walter Naegle, and they were together until Rustin's death in 1987. Without the option to marry, which wouldn't become possible until 2015's Obergefell v. Hodges decision, Rustin's best option was to adopt his partner. This arrangement, which passed muster because Naegle was thirty-some years his junior, gave the couple familial rights they wouldn't have had otherwise (including important financial protections) and was somewhat common prior to wider acceptance of gay marriage. But a formal adoption isn't the same as a marriage, and Naegle could only be listed as Rustin's adopted son and administrative assistant in his obituary.

He received a posthumous pardon and the Presidential Medal of Freedom

Unfortunately, Bayard Rustin didn't live long enough to benefit from changing public opinions, especially about sexuality ... a climate change that would've allowed him to marry and may have resulted in him getting the long overdue recognition he deserved. Still, some of the wrongs of the past have been corrected, at least on paper. In 2020, Rustin was posthumously pardoned for his 1953 sex perversion charge by California Governor Gavin Newsom. The measure was part of a concerted effort by Newsom to symbolically undo the injustice of such convictions. The Governor was urged to take these steps by the California Legislative Black Caucus and the California Legislative LGBTQ Caucus.

Seven years earlier, then-President Barack Obama awarded Rustin the 2013 Presidential Medal of Freedom (via The Washington Blade). In his speech, Obama said of Rustin, "For decades, this great leader, often at Dr. King's side, was denied his rightful place in history because he was openly gay. No medal can change that, but today, we honor Bayard Rustin's memory by taking our place in his march towards true equality, no matter who we are or who we love." His surviving partner, Walter Naegle, was on hand to accept the award on his behalf.