London's Secret World War II Tunnels Explained

Deep underneath London, there was once a secret world. Well, the city is so ancient that there are quite a few surprising bits of history beneath busy Londoners' feet, from evidence of ancient Roman occupiers, to early modern plague burials, to its long-standing subway system established in 1863. But, while a moderately invested student of history may already know about these things, there's no reason to stop there.

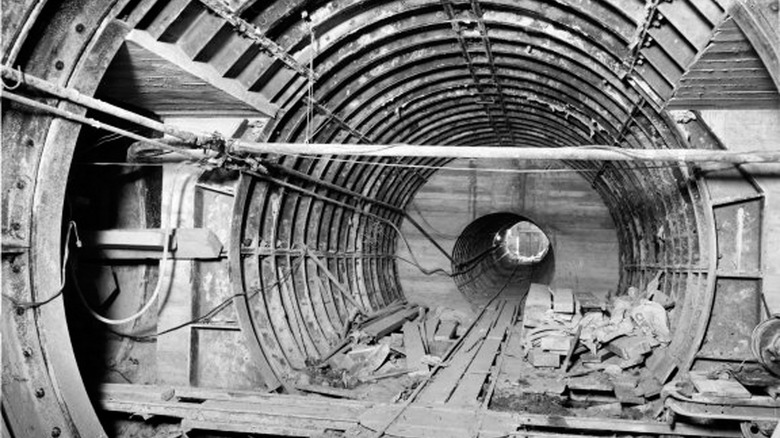

For something different, you might go to the Chancery Lane Tube station on the Central Line that runs beneath High Holborn Street. It may look like a normal stop on the London Underground, but about 130 feet below the surface is a unique collection of passages that is now commonly known as the Kingsway Exchange tunnels. First excavated during World War II, they're not especially old for a city that's been around for nearly 2,000 years. However, they are mightily impressive, with more than 86,000 square feet of space sprawling belowground.

Originally constructed as deep-level shelters to protect civilians from an onslaught of German bombs, the tunnels have since led a colorful, if rather mysterious life. With a story that includes Cold War intelligence agencies and bustling telephone exchanges, the Kingsway Exchange tunnels have quite a lot of history to share. With new development on the horizon, it's very possible that you can visit these tunnels to experience that subterranean history in person.

The tunnels were originally meant to be a wartime shelter

The Kingsway Exchange tunnels have their origins during some of the darkest days London faced in World War II. Using existing underground train tunnels, the British government began constructing public shelters meant to be used during air raids, when German pilots dropped bombs in an effort to beat Britain into submission. The effort by Axis powers culminated in what's now known as the Blitz, a bombing campaign that lasted from September 1940 to May 1941 and focused on London and other major cities. More than 43,500 civilians were killed during the Blitz. Of those who survived, many took shelter underground whenever they heard the blare of air raid sirens.

London's Chancery Lane shelter was ready to protect the city's people in March 1942 as part of a system of shelters dug deep underground. In this case, Chancery Lane was dug near a turn-of-the-century subway station. Civilians had already been taking cover in pre-existing London Underground stations. Yet, by the time the Chancery Lane shelter was ready, the government began to drag its feet. Opening it would be expensive, they argued. It would be cheaper to keep them to the side, just in case the Germans returned for round two of the Blitz. Thankfully, that never happened, and Chancery Lane remained an odd little bit of government property for the time being, with a brief stint as what were surely very unique accommodations for military service members.

It's part of a wider history of World War II underground London

By World War II, London was already dotted with an extensive network of underground passages. For instance, it had seen the world's first underground rail system back in 1863. Eighty years later, wartime leaders naturally took advantage of the underground.

Unlike the Chancery Lane shelters, many of these spots weren't strictly tunnels, while those that were couldn't be kept top secret. That second group mostly consisted of London Underground rail lines and stations, which had already been used as air raid shelters during World War I. They went back into similar use again during the Blitz and a later spate of German air raids from 1944 to 1945. Of course, with thousands of Londoners taking shelter there, it would have been confusing and impossible to turn these already public spots secret.

What was secret, however, were Prime Minister Winston Churchill's subterranean war rooms. Located in what seemed to be an unremarkable basement in Westminster, the warren of rooms acted as a government center even during intense bombing, with a dedicated cabinet room for wartime meetings, a bedroom for Churchill himself, and even a secret phone line to the president that was concealed as a private bathroom. Today, part of it is a museum known as the Churchill War Rooms. However, you may be disappointed to learn that Churchill's wartime warren — at least, the part you can visit today — is only about 12 feet underground.

A subsection of MI6 briefly moved in after World War II

As the war wound to a close, the shelter at Chancery Lane hosted a few government agencies, including part of London's civil defense force, the Port of London Authority, and the Inter Services Research Bureau. But that last agency was actually the research arm of the Special Operations Executive, which was itself a subsection of none other than the MI6 intelligence agency (also known as the Secret Intelligence Service) that would come to be a major player in the looming Cold War.

Of course, Britain's formidable intelligence agency wasn't about to set up shop with a custom-made sign and flashing lights, hence the secrecy. Workers who occupied the tunnels later in the century told The Guardian that they had heard the original construction workers who built the shelters didn't speak English, though that appears to be more rumor than verified fact (thanks, at least in part, to workers having to sign on to the Official Secrets Act before joining the underground team). It was clear, however, that getting to the tunnels meant entering a purposefully dull entrance that looked like any other doorway on the street far above.

Even after MI6 moved out in May 1945 and took everything with it, the later telecommunications equipment installed inside the tunnels remained a sensitive subject, especially given that it hosted a direct line between the Kremlin and the White House during some of the most tense days of the Cold War.

It housed a staggering number of public records

By 1945, the Public Records Office (PRO) was looking to move into the old Chancery Lane shelter. With a four-year lease in place, it began to use the two large tunnels to store hundreds of tons of documents deep below ground. However, PRO workers would have to hoof it. They were required to use only elevators and stairs at either end of the tunnels, as elevator access from the Chancery Lane underground stop was shut to keep a possible fire from spreading into the railway system.

A reporter for the Evening Standard wrote that, as staff were moving documents into the old shelter on January 10, 1946, they were returning some of London's most important documents to the city. During the war, with air raids striking the capital and other British cities, an estimated 2,000 tons of documents were transported out of the city and to safer spots in the countryside. But, as much as PRO representatives were concerned about keeping the records safe (and which they did during the war), the old Chancery Lane shelter wasn't purposefully chosen to house an estimated 400 to 500 tons of books and papers. Instead, as one official told the Evening Standard reporter, it was good enough for the task (which included housing about 80,000 feet of shelving) and, perhaps just as importantly, was available at the right time (via Subterranea Britannica).

The post office took over and expanded the tunnels

By 1949, the Public Records Office had moved out of the tunnels, which were next transferred to the General Post Office (GPO). At the time, the GPO was not just in charge of making sure mail was delivered but also oversaw telecommunications, and not just across Britain. By 1956, it hosted the U.K. terminal for TAT-1, the first transatlantic telephone cable, indicating the important and secure status of the deep tunnels.

Prior to that, the GPO oversaw an expansion project that added four smaller tunnels and additional access elevators before it officially opened in 1954. By this point, it was referred to as the Kingsway Trunk Switching Centre, Trunk Zone Exchange Kingsway, London Trunk Kingsway, or, for those who are more into brevity, simply the Kingsway Exchange. At one point, workers could get into the complex through one of two passenger elevators, though the last-known working entrances were at nondescript points on Furnival and High Holborn streets.

GPO officials believed that the tunnels would be a far more secure location for helping to maintain the country's all-important communications network. The previous terminal for the exchange system was at Faraday House, an above-ground structure that would have been vulnerable to all manner of attack, as survivors of the World War II air raids knew all too well. And, with the world still reeling from the globe-spanning war, it seemed prudent to plan with yet another conflict in mind.

The Kingsway Exchange handled a serious volume of calls

Under the direction of the GPO, the tunnels were meant to host and redirect telephone calls, though they also acted as a terminal for a major transatlantic telephone cable that made international communication easier. During the Cold War, it became all the more important in country-to-country calls, as it hosted part of the so-called "hot line" that made it possible for the White House and the Kremlin to communicate directly.

A 1969 edition of the Courier, a publication for Post Office workers, revealed the extent of the GPO's operations in the Kingsway tunnels more than two decades after it opened. It employed an estimated 200 people to manage about 6,000 simultaneous phone calls or up to 2 million per week. It all depended not just on human workers but a complicated network of cables that ran through about 12 miles of tunnels. However, it was once even more important in earlier decades, when human operators had to manually reroute all calls. Automated dialing systems helped alleviate the pressure, especially as other trunk-switching centers were added to the nation's network (via Subterranea Britannica).

Some details of the tunnels have remained quasi-secret

While few people were going into the street and shouting out the details of the Kingsway Exchange tunnels, they weren't exactly secret, either. Sure, many workers who passed through were obliged to sign the Official Secrets Act as a kind of confidentiality agreement, but a careful observer could have still figured it out. They would have to have looked pretty closely, however, as the entrances to the Kingsway Exchange were kept purposefully unremarkable, with no external signs or other markers identifying them as entrances to the tunnels.

Retired workers even told The Guardian of rumors that those who originally built the tunnels were selected in part because they didn't speak English, though those remain unsubstantiated. But it was obvious enough that, even after the tunnels were effectively declassified in the late 1960s, people remained pretty close-lipped about the existence of the Kingsway Exchange tunnels. As former facilities manager John Tasker told The Guardian in 2008, working there put you in a bit of a great area. "By then this place wasn't strictly secret — but it wasn't precisely not secret either," he said. "You just got into the habit of not talking about work to anyone outside."

Yet another worker, supervisor Richard Bamford, told the outlet that he wasn't about to explain exactly what streets carried vehicles far overhead. After all, anyone who was interested in purchasing the then-vacant tunnels might want to keep things hush-hush for their own reasons.

[Featured image by J WILLIAMS via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled | CC BY-SA 2.0]

They were reportedly locked down during the Cuban Missile Crisis

With the Cold War dominating much of the 20th century and fears of nuclear Armageddon creeping into the public consciousness, it was hard to let go of the shelter aspect of the Kingsway Exchange tunnels. If one of the greatest fears of the postwar era came true, could it have been used as a shelter for real?

It seems that people certainly wanted to keep that possibility open. A reporter for a 1946 edition of the Evening Standard, who visited the tunnels as the Public Records Office was in the process of taking over the space, noted the presence of bunks, kitchens, and food storage space that would have reportedly helped people survive in the shelters for up to a year. A 1969 Courier article likewise pointed out the cooling system in the tunnel, as well as its dedicated well and generators that came with enough fuel to operate for six weeks (via Subterranea Britannica).

All of this was reportedly put into practice, if only briefly, in the midst of the Cuban Missile Crisis. During the standoff between the United States and the Soviet Union in October 1962, many rightfully believed that the world was on the precipice of all-out nuclear war. Kingsway Exchange workers reported that the tunnels went on lockdown, with workers as ready as they could be to ride it out with a stockpile of food, artesian well water, and filtered air (via The Guardian).

Eventually, it included a bar and smoking area

By the 1980s, British Telecom took over the operations in the Kingsway Exchange tunnels. The group was once essentially the telecommunications offshoot of the General Postal Office, but the government-run group turned private in 1984. It occupied the tunnels until 1996, though British Telecom held onto the site for a few more years.

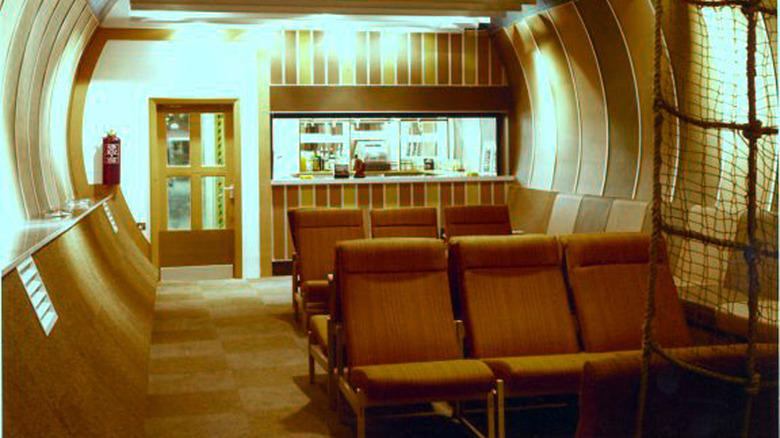

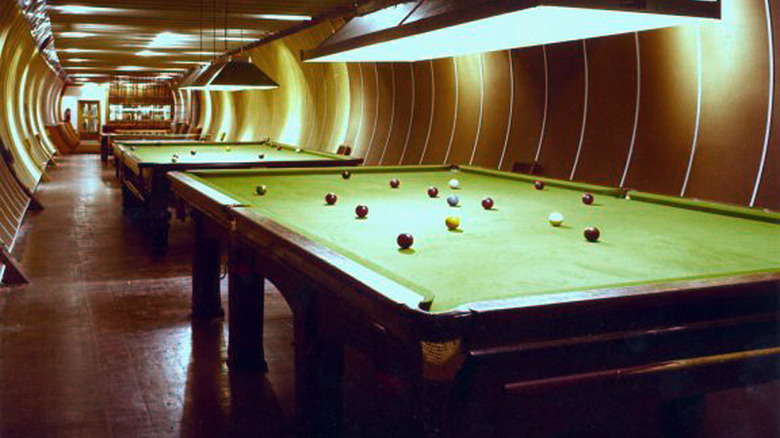

But, before technological obsolescence came for the hundreds of workers, thousands of lines, and miles of cables in the Kingsway Exchange tunnels, things could be pretty groovy. Even prior to the British Telecom takeover, staff could take advantage of multiple food areas, which included a relatively fancy restaurant that included fake windows outfitted with landscape images, as well as the more casual Tube 3 Tea Club that included a fish tank — which, at one point, was reportedly home to piranha that were implied to have eaten their tankmates.

If the tropical fish proved to be a bit much, workers could choose to relax in a bar that, true to the times, allowed smoking as long as staff members were sure to put their cigarettes out before returning to work. At the time, British Telecom oversaw what was believed to be the deepest bar in the world that was used by government workers.

It may now open up to the public once more

Even when it was in the privatized hands of British Telecom, the tunnel complex was kept quasi-secret, with workers getting into the habit of keeping their mouths shut about what went on deep below ground, even if they weren't obliged to work under the Official Secrets Act anymore. But then British Telecom (which had stopped using the tunnels in the 1990s and rebranded itself as BT around the same time) finally put them up for sale in 2008. News pieces describing the interior and interviews with former workers began to proliferate. Given the rather unusual location, a previously failed attempt to sell the spot, and a high asking price —- at the time BT was hoping for £5 million — a buyer wasn't guaranteed.

By 2023, however, it was in the hands of fund manager Angus Murray and his company, The London Tunnels. Speaking to Bloomberg, Murray was effusive about the potential of the space, which he plans to renovate for $269 million. "Would I compare this to be as iconic as the London Eye?" he said. "Yes, I would. Who wouldn't come here?" He spoke further of turning the space into a multi-use spot that would include history exhibits, multimedia experiences, and, of course, a bar. Nothing's open to the public just yet, but if Murray's enthusiasm is well-placed, you may very well be able to wander around the Kingsway Exchange yourself in the not-too-far-off future.