The Messed Up Truth About The Bosnian War

In the 1990s, the area of Bosnia and Herzegovina in the former Yugoslavia was awash with some of the worst violence of the 20th century. From 1992–1995 during the Bosnian War, at least 100,000 people died, many of them civilians. It's also thought that as many as 50,000 people were survivors of sexual assault, with the vast majority of the survivors being Bosniaks (Bosnian Muslims) and the perpetrators Bosnian Serbs.

The war was punctuated by numerous atrocities carried out by both Bosniak and Bosnian Serb forces, and the fighting savagely ripped apart the area and displaced millions. The fighting was precipitated by the split of the former Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia in the early 1990s, of which Bosnia and Herzegovina was one of six constituent republics. When Bosnia and Herzegovina declared its independence in 1992, Serbian nationalists did not want to live under a Bosniak-dominated government — they wanted their own autonomous Serbian government instead.

This disagreement led to three years of tragic war, killing thousands and leaving millions of shattered lives. Barely a year after the fighting began, an international war crimes tribunal was set up, and after the war both Bosnian Serb and Bosniak authorities faced charges. Several were later convicted, including infamous people such as Zdravko Tolimir, Ratko Mladic, and Radovan Karadzic. The Bosnian War was some of the most brutal fighting in recent decades, and here is the messed up truth behind it.

It was part of an even larger armed conflict

One of the most tragic things about the Bosnian War is that it was actually just a smaller part of a larger conflict called the Yugoslav Wars, which occurred as part of the dissolution of the former Yugoslavia. Since 1946, the country had officially been known as the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, and it consisted of six different republics, including Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, Serbia, and Slovenia. However, following the death of President Josip Broz Tito in 1980, the country began to decline economically and politically.

By 1991, Yugoslavia was breaking apart at its seams, and its subsequent internal divorce was extremely violent. The first dominoes to fall were Slovenia and Croatia, who declared their independence on the same day of June 25, 1991. In Slovenia, the "Ten-Day War” saw the Slovenians fight the Yugoslav People's Army (JNA). The Slovenians were successful, but the conflict still resulted in 63 total casualties and more than 300 total wounded. In Croatia, the fighting lasted far longer, until 1995, when the Croatians defeated the JNA and their Serbian allies, and it resulted in roughly 40,000 deaths.

In Bosnia, the fighting took place from 1992–1995, and it's estimated 100,000 people died. Yet, that wasn't the end. From 1998–1999, fighting in Kosovo in Serbia displaced more than one million people while claiming thousands of lives. Today, Yugoslavia no longer exists, but the wake of its destruction still looms large in the area.

The war started and ended with U.S. intervention

While the fighting during the Bosnian War took place in, well, Bosnia, the United States actually played a significant role in both the beginning and the ending of the war. Following the lead of their neighbors Slovenia and Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina declared its independence from Yugoslavia on March 3, 1992. Even then, there were clear tensions brewing internally between the Bosniaks and the Bosnian Serbs — the latter of whom did not want independence under Bosniak rule.

Those tensions continued to escalate until conflict erupted in early April. On April 6, the Bosnian Serbs began a four-year siege of Sarajevo after the Bosniak government started to mobilize against them. The following day, the U.S. (among others) formally recognized the new Bosnia and Herzegovina, and the Serbians responded with a ground invasion. The invasion spelled the beginning of the true war, which would last for nearly four years.

In addition to playing a role in the war starting, the U.S. also played a big part in the 1995 Dayton Accords that formally ended it. After U.S.-backed NATO airstrikes against the Bosnian Serbs in the summer of 1995, the Serbs agreed to end their siege of Sarajevo and attend peace talks in Geneva. U.S. President Bill Clinton was active in the diplomacy and helped get the final agreement signed. While this certainly wasn't an American war, the United States clearly played an outsized role in it.

The saga of Ilija Jurisic

Unfortunately, the fog of war often makes it impossible to know exactly what happened during a certain event. That appears to be the case with Ilija Jurisic, a former police officer in Tuzla in eastern Bosnia. Jurisic was working as a police official when gunfire broke out between the Yugoslav People's Army (JNA) and the Bosnian Territorial Defense forces at the beginning of the Bosnian War in May 1992 (via Balkan Insight).

Apparently, the JNA had permission to withdraw from the area, when the Bosnians and some of Jurisic's police forces began firing on them. The Serbians regarded the shooting of their withdrawing troops as a war crime, and they wanted Jurisic held responsible for ordering the attack. However, Jurisic's recounting of events has the JNA forces firing on his police officers first. Jurisic claims he was just ordering return fire and not initiating anything, but that eventually became the purview of the courts to decide — except they couldn't.

Jurisic lived free for over a decade after the war until he was arrested in 2007 at a Serbian airport. In 2009, he was convicted of war crimes and sentenced to 12 years in prison, but a retrial was held after the original conviction was overturned on appeal. In 2013, he was once again given the same sentence, which was again overturned on appeal in 2016. Today, Jurisic walks free and is widely seen as a hero in Tuzla, but his case truly demonstrates the anger and tension over the fighting in Bosnia.

There was a Serbian concentration camp run by Bosnians

The Bosnian War was marked by atrocities throughout the fighting, and they took a horrible toll on the population. One of the worst examples was the Celebici detention camp near Konjic in southern Bosnia and Herzegovina. When the war broke out in April 1992, Konjic was held by Bosniak forces, but 15% of the local population identified as Serb [via the International Crimes Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY)]. Though much of the population fled, a good deal stayed behind in their homes.

Yet, when the Serbian-allied Yugoslav People's Army began firing on the town and the Bosniaks decided to mount a counteroffensive, the Bosniaks rounded up many of the remaining Bosnian Serbs and put them in a makeshift concentration camp in the village of Celebici. The camp was open for eight months, and the Serb prisoners were subjected to horrifying abuse. Several prisoners were sexually assaulted and raped, and others were tortured through electrocution, had their pants set on fire, were prodded with hot pincers, or were beaten with baseball bats.

The camp and war forever changed the character of Konjic, which was only 2% Serb by 1996. Eventually, three men (including guard Esad Landzo and camp commander Hazim Delic, pictured above) were convicted of war crimes and sentenced to 9-18 years of imprisonment for their actions at Celebici. Celebici showed the horror that many Bosnians and Bosnian Serbs experienced during the war, and its scars will never truly fade.

The crazy Banja Luka incident

While many people might not be familiar with the name Scott O'Grady, back in the mid-1990s he was one of the most visible faces of the American intervention in the Bosnian War. O'Grady originally joined the Air Force in the late 1980s, and by the early 1990s he was flying missions with NATO in his F-16. O'Grady participated in NATO's first-ever combat mission, which took place in 1994 during the Bosnian War.

O'Grady was still flying missions for NATO when Bosnian Serb ground forces near Banja Luka in Bosnia and Herzegovina sent a surface-to-air missile at his aircraft on June 2, 1995. The missile scored a direct hit on his F-16, but luckily, O'Grady was able to eject instead of crashing with his plane. He could see the Serb soldiers chasing him as he descended to earth. O'Grady, who suffered burn wounds during the initial explosion, was on the ground behind enemy lines for six days and nights, finally being rescued by a contingent of Marines on June 8 from a desolate Bosnian mountaintop.

While on the ground, O'Grady had to skillfully avoid enemy patrols, which included helicopters, and he was almost discovered by nearby troops several times. Without rations, he had to eat ants and drink rainwater, but he survived. Undoubtedly, O'Grady has a claim to one of the all-time craziest war stories, and it supposedly even inspired the 2001 movie "Behind Enemy Lines."

The United Nations hostage crises

From the beginning, the Bosnian War had the dimensions of an international conflict, and the United Nations was there from very early on. The first U.N. troops to the area were 14,000 peacekeepers sent to the fighting in Croatia in February 1992, and when shooting broke out in Bosnia and Herzegovina, some were sent there, too. By April 1994, there were roughly 13,000 U.N. troops in Bosnia, including soldiers from Sweden, France, and Canada (per The Washington Post).

Unfortunately, the U.N. peacekeepers became targets for the Serbian ground forces to kidnap. The first incident happened in April 1994, when Bosnian Serbs began harassing and arresting as many as 200 U.N. personnel. In November 1994, the Serbs struck again, taking hostage 450 U.N. peacekeepers from Great Britain, Canada, the Netherlands, Ukraine, Russia, and France following NATO airstrikes, but that wasn't the last incident (via The New York Times). In May 1995, Bosnian Serbs took 370 U.N. peacekeepers hostage, finally releasing them on June 19 (via The Washington Post).

It's difficult to imagine just how harrowing it must have been for the soldiers who were kidnapped and imprisoned by the hostile Bosnian Serb forces. By the time of the first U.N. hostages were taken in April 1994, the atrocities being committed by the Bosnian Serbs were already well known, and the U.N. troops must have been terrified. Luckily, the Bosnian Serbs released the hostages before killing them, but things could have turned extremely ugly quickly.

The dual Kravica massacres

Due to their use of the Julian rather than Gregorian calendar, Orthodox Christians celebrate Christmas on January 7 rather than December 25. Unfortunately, in 1993 in the village of Kravica in eastern Bosnia and Herzegovina, Orthodox Christmas coincided with one of the most tragic days in Bosnian history: the first Kravica massacre.

Bosniak forces carried out the massacre of Bosnian Serbs, and the terror must have been unthinkable. In all, witnesses claim the Bosniaks killed 48 civilians and set their houses on fire, forcing many to flee to the woods and survive in the wilderness for days (via the Balkan Insight). When some did finally make it back, Bosniaks took them away to torture them and imprison then, killing some of them too.

Sadly, that wasn't the end of the killing in Kravica. Two years later, in July 1995, the second Kravica massacre took place in a warehouse (pictured above) when Bosnian Serbs claimed the lives of 1,000-1,500 Bosniak men (per the ICTY). The Bosnian Serbs used grenades and machine guns to kill the men after first trapping them in the building. There were only a few known survivors who managed to escape and testify, and in 2012 Bosnian Serb general Zdravko Tolimir was convicted of genocide for ordering the massacre, along with several other mass executions that, all told, killed an estimated 6,000-8,000 Bosniak men and boys. The dual massacres at Kravica are an incredibly sad legacy for the town, and speak to the absolute devastation of the war.

The tragic murder of Hakija Turajilic

One of the most significant moments in the early fighting of the Bosnian War was the assassination of Bosniak Deputy Prime Minister Hakija Turajlic. The killing occurred on January 8, 1993, while Turajlic was under the protection of United Nations peacekeeping forces, and the culprits were Bosnian Serbs (via The New York Times).

Turajlic's murder took place as he and his protectors were exiting the Sarajevo airport upon his return to Bosnia, and they only got 500 yards into the city before being stopped by about three dozen Bosnian Serb soldiers. The Serbians and Turajlic's French-United Nations escorts argued, but the French refused to release Turajlic, and things turned deadly after about an hour and 45 minutes. Finally, the Serbians fired upon Turajlic while he was still sitting in the U.N.'s armored personnel carrier, killing him instantly.

Following Turajlic's death, there was a lot of finger-pointing on the Bosniak side. The Bosniak government accused the U.N.'s military commander, Gen. Philippe Morillon, of a cover-up in the aftermath, and citizens took to the streets calling for Morillon's head (via The New York Times). It was one of the most brutal deaths for any government official during the war, underscoring the relentless, often guerilla nature of the fighting. In 2002, Serb Goran Vasic was acquitted of the killing in a trial in Sarajevo (per the Associated Press via The New York Times), and no one else has been charged as of October 2023.

[Image by Christian Marechal via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled | CC BY-SA 3.0]

The controversial tale of Naser Oric

If there is one case that demonstrates the dichotomy of the Bosnian War, it's that of former Bosniak commander Naser Oric. Before the fighting, Oric was a member of the Serbian-allied Yugoslav People's Army (JNA). At one point he even guarded infamous Serbian politician Slobodan Milosevic, who would later be indicted for war crimes against the Bosniaks.

When the war broke out in 1992, Oric became a commander of the Bosniak Territorial Defense forces. He defended Srebrenica from 1992–1995, and it's during this time that he allegedly committed various war crimes. The Hague indicted Oric in 2003 for seven murders between 1992–1993 of Bosnian Serbs, for destroying Serbians' homes and villages unnecessarily, and for the illegal treatment of 11 others. He was also implicated in the 1993 Kravica massacre that killed dozens (via Balkan Insight), and in the 1993 Skelani massacre that killed 69 (via Sarajevo Times).

Oric was arrested in April 2003 and put on trial for war crimes. He was convicted in 2006 and sentenced to two years in prison, but the conviction was overturned in 2008 upon appeal. In 2016, Oric again found himself on trial, this time in Sarajevo, but he was acquitted of war crimes involving the murders of three prisoners of war. Not surprisingly, Oric is beloved by many Bosniaks and hated by many Serbs — a sad representation of the divide in the country that claimed so many lives for so many years.

The $6 million swindle

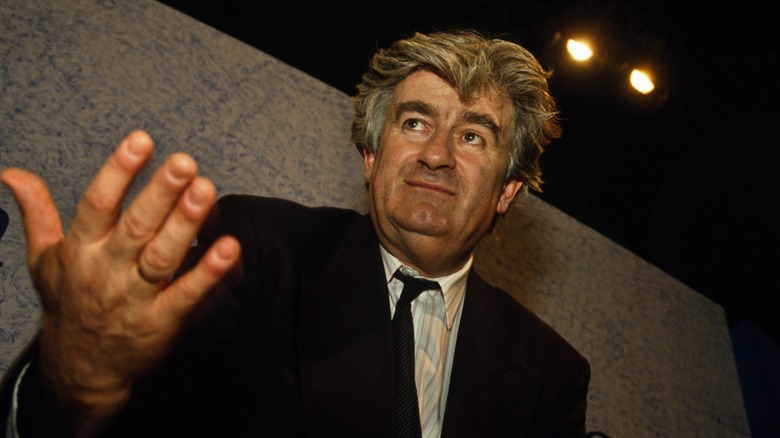

By January 1995, Bosnian Serb leader Radovan Karadzic (pictured) was ready to make a deal. It was nearly three years into the war, the Bosniaks were not giving up, and international NATO forces had already been called into action to attack Karadzic's fighters. Sometime that January, the desperate physician-turned-politician met with a man he thought was a Liberian arms dealer named Nikolas Oman (per The New York Times).

In their meeting, Oman sold Karadzic on a miniature nuclear bomb that could cause untold destruction without leaving lingering radiation. He called it "Red Mercury," and they made a deal for Karadzic to purchase some for $66 million. Yet, little did Karadzic know, Oman was lying, and "Red Mercury" was a myth. Tales of Red Mercury had begun gaining steam in the early 1990s, largely thanks to bad reporting from Russian state news organizations and Britain's Channel 4, but it has never been proven real and pretty much every reputable source agrees it's not viable or even realistic.

When Karadzic gave Oman's associates the first $6 million, they discovered they had been duped, and the "Red Mercury" was actually just red jelly. In hindsight, the incident speaks volumes about Karadzic's aims during the war. Nuclear weapons have only been used two times, and the world is still debating their efficacy nearly a century later. To think they could have been used in Bosnia in the early 1990s if Karadzic had gotten his hands on one is pretty stunning.

The April 16, 1993 massacres

For residents of the villages of Ahmici and Trusina in Bosnia and Herzegovina, one of the most harrowing days of the Bosnian War was April 16, 1993. That day at the two villages, which are separated by about 60 miles, opposing Bosnian Croat and Bosniak forces killed more than 130 civilians and seven soldiers during nearly simultaneous massacres.

At Ahmici, Bosnian Croat soldiers — who were fighting the Bosniaks in the Croat-Bosniak War that was taking place amidst the larger Bosnian War — killed 116 Bosniak civilians. When British soldiers showed up a few days later, they found the village destroyed and inhabitants murdered, including women and children, and some of the bodies had been burned. Sadly, while the British were investigating, one of them — a Serb interpreter — was felled by a sniper's bullet, likely from a Croatian soldier. At Trusina, the Bosniaks allegedly used women and children as bargaining chips, holding them hostage to compel their loved ones to surrender. They eventually killed 15 civilians and seven Croatian soldiers, and the screams were audible in a nearby village.

Eventually, some of the perpetrators of both massacres would later be convicted and sentenced to various prison terms. Today, both villages have memorials paying respect to the victims of the massacres, and the pain is still deep for the residents. They were two incredibly tragic atrocities in a war that was disturbingly full of them, and they are not forgotten today.

[Photograph provided courtesy of the ICTY.]

Many war criminals legally immigrated to the United States

Early in the fighting of the Bosnian War, the United Nations became aware of ongoing war crimes. As a result, they set up a war crimes tribunal in May 1993 to investigate and eventually prosecute the perpetrators. However, in the fog and chaos of the war and its immediate aftermath, many war criminals were able to escape prosecution and in some cases even flee the country.

Stunningly, many of those war criminals seem to have made their way into the United States — and they did so through legal immigration. According to The New York Times, by February 2015, authorities had identified 150 Bosnians who had allegedly committed war crimes during the fighting before moving stateside, and they were looking to remove them back to Bosnia to face trial. In addition, there were another 150 or so who were also believed to have committed atrocities but were not yet being deported.

The arrests largely began in 2004 when authorities captured Bosnian Serb Marko Boskic, who was eventually deported and sentenced to a decade in prison in Bosnia. Since then, several U.S. citizens have been arrested, deported, or stripped of their citizenship, including Azra Basic in 2016, Edin Sakoc in 2015, Slobo Maric in 2019, and Rasema Handanovic in 2019. It's disturbing to think even more Bosnian war criminals might be walking down the street among us, but hopefully that isn't the case.

The world's most dangerous market

While the majority of Bosnia and Herzegovina was engulfed in fighting during the Bosnian War, some parts of the country were definitely hit harder than others. Without a doubt, one of the most devastated of the entire war was the capital city of Sarajevo, which faced a four-year-long continuous siege that took the lives of more than 11,500.

Within Sarajevo, there seemed to be one place that was particularly unlucky: the Markale marketplace (pictured above in 2006). Markale had the unfortunate distinction of being hit by shells from Bosnian Serb forces in both 1994 and 1995, causing the deaths of more than 100 Bosniak citizens as well as injuries to more than 200.

The first bombing took place on February 5, 1994, and cost the lives of 68 people while wounding 140. According to eyewitnesses, the Serbian shell ripped people apart when it exploded, scattering body parts around the market (via Balkan Insight). The second bombing happened 18 months later in August 1995 in the waning months of the war. It was the same circumstances — a Bosnian Serb shell exploding at the market — and this time 43 died while 84 were injured. In 2006, Bosnian Serb commanders Stanislav Galic and Dragomir Milosevic were convicted of war crimes for the shellings of the Markale market and sentenced to lengthy prison terms. The Markale massacres remain sad reminders of the horrible civilian tolls of the fighting.

[Image by Christian Bickel via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled | CC BY-SA 2.0]

100,000 people died due to so-called ethnic cleansing

Looking back at the Bosnian War three decades after it first broke out, one of the saddest legacies of the fighting was the atrocious campaign of ethnic cleansing carried out against the Bosniak people. Now known as the Bosnian Genocide, the killings were largely committed by Bosnian Serb forces and their allies in the Yugoslav People's Army (JNA). In addition to Bosniaks, the Serbians also targeted the Croatians, who they were also fighting a war against at the same time.

When the former Yugoslavia began to split apart in the early 1990s, the Bosnian Serbs did not want to become part of another nation like Croatia or Bosnia and Herzegovina — they wanted Serbia to subsume the others and be the dominant force in the region. Unfortunately, Bosnian Serbs and their Serbian allies did not just want to conquer the territory; they wanted to erase the Bosniak and Croatian populations from existence. To do so, the Bosnian Serb and JNA forces began wantonly murdering civilians, including through the use of concentration camps. The worst genocidal spree occurred in Srebrenica, when Bosnian Serbs murdered as many as 8,000 Bosniak men within a single month.

After the war, several Serbians were convicted of war crimes related to the genocide, including Bosnian Serb general Ratko Mladic and leader Radovan Karadzic. The world hadn't seen ethnic cleansing on this scale since the tortuous days of the Holocaust, and hopefully it never will again.

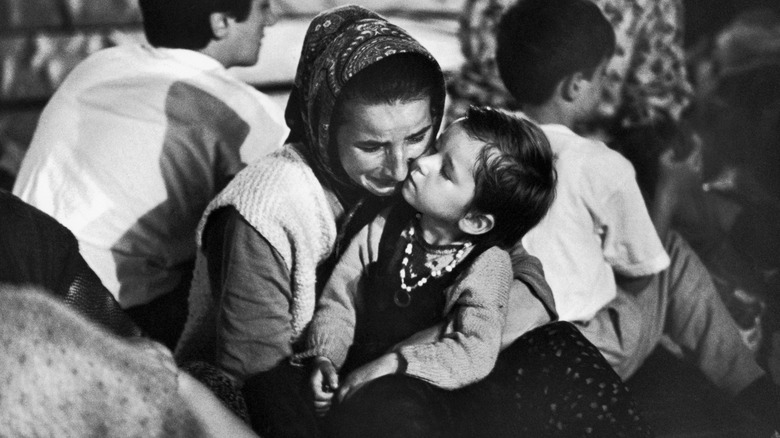

Sexual assault was used as a weapon

Undeniably, the Bosnian War brought to the surface some of the worst aspects of humankind. Tragically, for much of the war this included the systematic and genocidal rape of Bosniak women, mainly by Bosnian Serb men. As part of their larger ethnic cleansing aspirations, the Serbians began impregnating Bosnian women through a campaign of systematic rape (via Elizabeth A. Kohn in the Golden Gate University Law Review).

They wanted to dilute the Bosniak bloodline and impart Serbian blood, to make the future Serbian state they were going to proclaim after the war as homogeneously Serbian as possible. It was a horrifying plan, and resulted in the rape of anywhere from 20,000-50,000 Bosniak women from 1992–1995. Sadly, the knowledge of the abuse was already widespread within the first year of the war, and The Washington Post was even publishing firsthand accounts by December 1992. The article already dealt with the soul-crushing existence of "rape motels," or places were Serbian soldiers would forcibly abuse young Bosniak women after kidnapping them.

The abuse left trauma and scars that will likely never go away for some, and even decades later many victims are still terrified to speak out about what happened for fear of social stigmatization and isolation. As of 2011, the International Crimes Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia has only indicted about 70 people and convicted almost 30 for sexual offenses during the war.

Serbians killed thousands of Bosniaks in just a week

Within the Bosnian War, one of the most poignant events was the horrific Srebrenica Massacre in July 1995, carried out by Bosnian Serbs. It took place mainly during the week of July 11–16, and it's not hyperbole to call it one of the most devastating and blood-soaked weeks in all of human history. Since 1993, the area had officially been declared a safe zone by the United Nations peacekeepers, but that did absolutely nothing to stop the 1995 Serbian onslaught.

The week prior, the Bosnian Serbs invaded Srebrenica, causing much of the Bosniak population to flee out of fear of being captured. They largely went to the United Nations' compound at Potocari, but the facilities were too small to accommodate them. Stranded, the Serbians caught up to them and forcibly separated the women and children from the men. After lying and telling them they would be freed, on July 12, the Bosnian Serbs began massacring the Bosniak men in Bratunac, Bosnia. The next day they started the mass killing, beginning with the Kravica massacre. Within hours, at least 1,000 Bosniaks were already dead.

There were further mass killings in the next few days, leading to countless more deaths. It's thought between 7,000-8,000 Bosniak men and boys had died by the end of July, with at least 5,200 of them before July 17. It was an appalling level of murder, and the mass graves are a constant reminder of the horror.

The Butcher of Bosnia

Of all the sadistic war criminals to have been involved in the Bosnian War, no matter which way you slice it, former Bosnian Serb commander Ratko Mladic was clearly one of the very worst. A member of the Yugoslav People's Army (JNA) since the days of Yugoslavia president Josip Broz Tito, Mladic fought briefly in the Croatian War of independence before moving to the Bosnian theater in 1992. He immediately became the head of all Bosnian Serb forces through the end of the war, a role which later earned him numerous war crimes convictions.

During the war, Mladic is thought responsible for some of the worst atrocities, including the Siege of Sarajevo, which killed more than 11,500 people, and the Srebrenica Massacre that killed 7,000-8,000 Bosniak men and boys in a single month. Far from being just a commander, Mladic is said to have played an active role in the destruction, and his methods were so heinous, and so tragically effective, he eventually gained the infamous nickname the "Butcher of Bosnia."

Mladic was able to escape punishment for a few years after the war living in Serbia, and in 2001 he disappeared for 10 years after fleeing. However, he was finally brought back to The Hague to stand trial in 2012, and in 2017 he was convicted of 10 war crimes. Thankfully, Mladic is still in prison, serving a life sentence that was upheld on appeal in 2021, and he'll never get out.

The Bosnian Serb president is a war criminal

Along with Ratko Mladic, former Republika Srpska (Bosnian Serbia) President Radovan Karadzic is one of the most visible faces of the nastiness of the Bosnian War. Karadzic was a trained doctor and published children's author before the war (which somehow makes him even more sinister), but was convicted of fraud and sentenced to prison in the 1980s. A founder of the Serb Democratic Party, Karadzic became the Republika Srpska president upon its founding in 1992. By virtue of being the head of government, Karadzic is responsible for playing a part in the Bosnian Serbs' sadistic genocidal efforts, leading to his indictment by the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia (ICTY) for war crimes.

A signer of the war-ending Dayton Accords, Karadzic was already under indictment when the war came to a close. Ironically, under the very Dayton Accords he signed, Karadzic was barred from maintaining the presidency due to indictment for war crimes, and he fled instead of facing trial. In 2008, Serbian authorities finally detained him, and his trial at The Hague began the following year.

Nearly eight years later, he was convicted of genocide and other war crimes, and sentenced to 40 years in prison. However, upon appeal the judges had a problem with the sentencing — they thought it was too light. He was later sentenced to life in prison, where he still remains today.

If you or anyone you know has been a victim of sexual assault, help is available. Visit the Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network website or contact RAINN's National Helpline at 1-800-656-HOPE (4673).