The Untold Truth Of The Real Captain Morgan

Whether you're an avid rum-chugger or a massive teetotaler, you've probably heard of 17th-century knight and nautical conqueror Sir Henry Morgan, better known as Captain Morgan. The rum that bears his name has been around since 1944 and originated in Jamaica, a nation Morgan invaded and where he later served as lieutenant governor.

You may have also heard the Captain Morgan rum slogan: "Got a little Captain in you?" Good question, but it actually raises other, even better questions, such as "Is the slogan encouraging me to eat a small naval officer?" and more importantly "Who exactly is this captain?" After all, you are what you drink, and since you should know thyself, you should know the captain. But even if you never get a little captain in you, you can still get fascinating info about him. So sit back with a glass of your favorite beverage and read the untold truth of the real Captain Morgan.

He wasn't quite a pirate

Henry Morgan is often thought of as a pirate, which is understandable. He's associated with bottles of rum. The Captain Morgan logo depicts him wearing a pirate-y hat and a pirate-y coat and practically yo-ho-ho-ing at you with his pirate-y eyes. The logo's creator, Don Maitz, studied pirates for years and considered Morgan a pirate. Plus, the real-life Morgan commanded a band of Caribbean pirates called the Brethren of the Coast. However, he wasn't a pirate, at least not most of the time.

Technically, he was a privateer, which was like a pirate, "only legal." A maritime mercenary for the British monarchy, Morgan raided Spanish territories and protected British trade routes in the Caribbean and was knighted for his efforts. In exchange for being a royal pain in Spain's backside, he kept whatever booty he looted. The journal Global Change, Peace & Security noted that both pirates and privateers facilitated state-building and impacted trade during the 17th and 18th centuries, which somewhat muddied the distinction. Some privateers even became pirates in peacetime.

However, between 1650 and 1750 the difference between pirates and privateers became more pronounced as war grew more organized. (Morgan was primarily active during the 1660s and 1670s.) Privateers were increasingly incorporated into naval strategies, and Britain in particular viewed privateering as a state-sanctioned business practice. Meanwhile, "piracy became ever less tolerated" because of its damaging impact on trade.

Morgan's biographical gaps

It's believed that Henry Morgan was born around 1635 in Wales, and he definitely died in 1688 in Jamaica. But the specifics of his lineage and how he ended up in the Caribbean are unclear. Surgeon Alexandre Exquemelin, who joined Morgan on his journeys, wrote that Morgan's father was "a well-to-do farmer." However, Professor David Williams pointed out that attempts to pinpoint Morgan's parentage assume he was biologically related to the Morgans who resided at the Tredegar House mansion. There's no convincing evidence of this connection, which even the U.K. National Trust acknowledges despite celebrating Morgan's supposed ties. It's also possible that he married a woman whose father was related to the Morgans of Tredegar.

As for how he reached the Caribbean, Exquemelin alleged that Morgan took to the sea to escape the agrarian lifestyle but was abducted and sold into indentured servitude. After completing his service, he supposedly joined the voyages of buccaneers and made his way to Jamaica. In an alternative account summarized by the University of Georgia's Classic Journal, he went to the Caribbean voluntarily to help Oliver Cromwell conquer Spanish colonies. Morgan outright denied ever being kidnapped and sold, and later characterized many of Exquemelin's claims about him as libelous. However a record of indentured servants from that period lists a Henry Morgan from Wales. Coincidence? Professor Williams didn't think so.

Snakes on a plate

Many people associate Jamaica with Bob Marley and marijuana. But the Jamaican Information Service likens the island to "a woman with a history" who "lived her life rapidly" and had "incalculable treasures poured into her lap by the old time buccaneer pirates." The man who led those pirates to their greatest heights was none other than Captain Morgan. In 1655, Morgan and his fierce buccaneers aided England's effort to seize Jamaica, which had been in Spain's possession since Christopher Columbus claimed it in 1494. But for as tough as the buccaneers were, they mostly got their butts kicked.

According to The English Conquest of Jamaica, England's Lord Protector Oliver Cromwell was overconfident and underprepared when he set out to occupy the island. There was little consideration of how perilous it would be, and Morgan and his men went through hell. As detailed in the book Henry Morgan, they were ravaged by an army of tropical diseases, including smallpox, malaria, and yellow fever. Things got even more complicated when they ran out of cattle to eat. Spanish snipers prevented Morgan and co. from venturing inland for food, forcing them to eat snakes and dogs. Morgan survived his trial by gunfire and would later be named Jamaica's lieutenant governor.

Battle of the boat bomb

Captain Morgan's various exploits led to legendary showdowns at sea. One of the most dramatic was a fiery confrontation with Spanish Admiral Don Alonso del Campo y Espinosa in 1669. Espinosa cornered Morgan in Maracaibo, Venezuela, then a Spanish territory. As recounted in Chronological History of the West Indies, Morgan had entered the city unimpeded and rooted out 250 frightened, hiding residents, whereupon he tortured them into divulging where their loot was. Before Morgan could depart, Espinosa arrived with three heavily armed warships and ordered Morgan to release his prisoners and relinquish his loot or prepare to get wrecked.

Though utterly outgunned, Morgan put up his nautical dukes. Luckily, he was cunning. His crew converted a vessel into a fireship, meaning they equipped it with combustibles or explosives. To conceal the ploy, they fitted the ship with objects meant to resemble guns and disguised pieces of wood as people. Their boat bomb annihilated a Spanish vessel, and another warship was run aground and set ablaze to keep Morgan from capturing it. However, the privateer wasn't out of the woods yet. In order to escape with his riches and life intact, he feigned preparations for a land-based attack so Espinosa would aim his weapons in the wrong direction. Then, when the Spanish weren't looking, Morgan's ships drifted to safety under the cover of darkness.

A ransom fit for a king's mercenary

If fortune favors the bold, then Captain Morgan probably had the biggest set of cannonballs in the Atlantic. In 1668, he pulled off what economic historian Peter Earle called "perhaps the most successful and audacious amphibious operation of the seventeenth century." Faced with the threats of disease and violent resistance, Morgan launched an assault on Portobello. Per the BBC, Portobello was a treasure port in the Spanish Main where Panama City stored its riches during the dry season. Unwilling to risk a frontal assault on his ships, Morgan commandeered 23 canoes, sneaked along the coast, and ambushed the town by land.

Portobello was caught completely off guard, and Morgan wasted no time bringing the place to its knees. He held all of Portobello for ransom, demanding 340,000 pesos from Panama City's governor in exchange for Morgan not setting the entire town on fire. And just to rub it in, Morgan referred to Portobello as an "English town." The governor begrudgingly complied, and Morgan made a tremendous amount of money.

The wrath of Captain Morgan

When Morgan forced Panama City's governor to pay a massive ransom for the town of Portobello in 1668, exchanges between the two men got pretty testy. The governor didn't think Morgan was fit to lick his boots and wasn't afraid to say it. In a letter he would live to regret a thousand times, the governor called Morgan an "inferior person" and a pirate. "People didn't say that to Henry Morgan," according to the BBC. He took his status seriously and considered himself a privateer. Now Panama City would have to learn the hard way that hell hath no fury like an insulted Captain Morgan.

Everybody doubted him. Panama City was one of the richest ports in the New World, and just getting there would require surviving 70 miles of disease-infested jungle. But not only did Morgan attack Panama City, he did it with "the largest fleet ever seen in the Caribbean," per CNN. In 1671, that fleet, consisting of 38 ships and more than 2,000 men, laid waste to the Spanish Main as they murdered their way to Panama City. When they finally reached the city, they spent a month torching houses and torturing residents. The governor had already escaped with literal boatloads of treasure, so the heist wasn't as lucrative as expected, but Morgan got his revenge.

The flaming arrow of San Lorenzo

Some stories are so awesome that no matter how obviously made-up they sound your heart partly believes them. The tale of the flaming arrow of San Lorenzo might be that story for you. It occurred during the early portion of Morgan's Panama City campaign. As recounted by Adventures in History Land, in order to bring the pain to Panama City, Morgan's men had to get past the fort of San Lorenzo. Tasked with completing that mission was Colonel Joseph Bradley, who rounded up 470 men and formed a three-ship squadron.

Morgan's forces had a lot working against them. Someone had tipped off the Spanish, who were ready to rumble by sea and land. While attempting to assess what they were dealing with, Bradley and company were met with whizzing cannonballs from the fort. In addition they had dangerous coral reefs to worry about. Things went badly during the battle until a "freak incident" turned the tide for Bradley and the buccaneers.

Supposedly, one of the buccaneers was struck with an arrow mid-retreat. Enraged, he wrapped the arrow in cotton and shot it back with a musket. Presumably the gunpowder ignited the arrow, which struck one of the fort's thatched roofs, and a massive fire ensued, intensified by grenades. A loaded bronze cannon exploded, blowing a hole in the wall. When all was said and done San Lorenzo's fortification was reduced to rubble.

Dishonor among thieves

Thieves don't steal for free. The whole point of forming a ring of plunderers is to enhance the chance of a successful heist so everyone involved can enjoy a ginormous payday. However, if surgeon Alexandre Exquemelin is to be believed, after the sacking of Panama City, Captain Morgan left his men in a lurch and made off with "the greatest and best part of the spoil, which had been concealed from them in the dividend."

It was the kind of double-cross that seems too low for the lowest lowlife to attempt. Morgan and his men had braved a 70-mile death trap of diseased jungle together and toppled one of the most famous places in the western hemisphere. Could modernity's favorite captain/beverage have really done something so vile? No way, said a totally unbiased Morgan. And just in case you don't believe a professional murderer and thief, Morgan's denial was supported by author Philip Ayers, who in 1684 wrote a much more flattering account of the captain's conduct in order to "rescue the Honor of that incomparable Soldier and Seaman Henry Morgan from those that would load him with the blackest infamy."

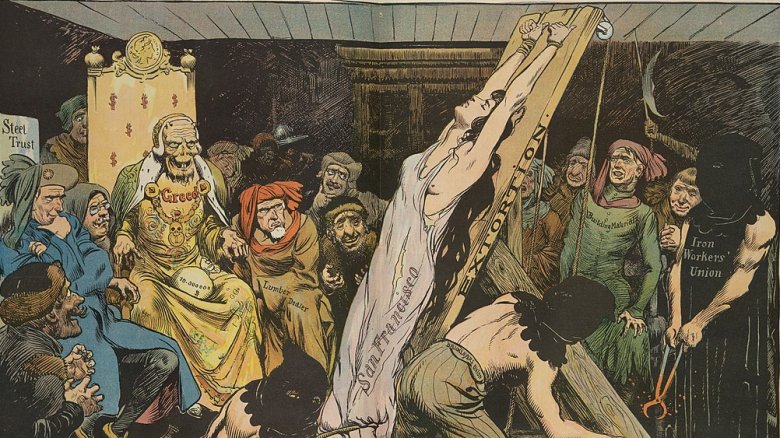

The morbid side of Morgan

People who kill and pillage for a living are bound to do some gruesome things, and Morgan was reportedly no exception. In fact, his surgeon, Alexandre Exquemelin, portrayed him as exceptionally cruel. In his 1678 work Buccaneers of America, Exquemelin described the kind of violence that would make your nightmares have nightmares. In one such account, Morgan held an elderly Portuguese man prisoner, believing him to be wealthy. When the prisoner insisted he wasn't rich, Morgan men supposedly stretched the old man's limb with cords, "breaking both his arms behind his shoulders." They also placed flaming palm leaves underneath him, burned his face, set his hair on fire, placed heavy stones on his joints, and starved him within an inch of his life.

In another hideous incident Morgan supposedly imprisoned people and had their heads compressed with cords until their eyes burst out. And in another, countesses were supposedly roasted over coals. Morgan's own accounts of his exploits were far less salacious, but as the BBC pointed out, the captain had "very skittish political backers" and might have wanted to avoid gruesome descriptions.

Morgan has the final say

The cliche "History is written by the winners" was never truer than in Henry Morgan's case, specifically the court case in which he sued his surgeon's publishers for libel. He didn't take kindly to the writings of Alexandre Exquemelin, who had essentially portrayed him as an abductee forced into indentured servitude who became the most ruthless and rabid of sea dogs under the tutelage of pirates.

Per UC San Diego's special collections library, Morgan's main gripe was being described as an indentured servant. However, there were a few alleged acts of violence he wanted scrubbed from the record. According to the Marin Independent Journal, Morgan took issue with the claim that he used nuns and priests as human shields while raiding a Spanish colony. After being knighted by England and appointed Jamaica's lieutenant governor, Morgan filed and won a lawsuit that forced Exquemelin's publishers to make a series of awkward retractions, including one which said that Morgan didn't "hang up any person by the testicles."

According to the Classic Journal, it's likely that Exquemelin took at least some creative license when describing Morgan's exploits, but that doesn't mean he lied outright, and the claim Morgan denied most vehemently –- that he was an indentured servant –- was supported by concrete evidence. Contemporary records indicate that someone with Morgan's name who came from his native Wales was absolutely sold into servitude.

The search for Satisfaction

Dead men tell no tales, but dead ships can tell you a lot about dead men. Captain Morgan lost five of his vessels during his travels. Among them was his flagship, Satisfaction, which sank in 1671 during the campaign to sack Panama. With partial funding from the Captain Morgan rum company, archaeologist Frederick Hanselmann led an expedition to find Morgan's sunken ships. In March 2011 his team uncovered six cannons from the captain's fleet, per the Independent, and in August they found something remarkable.

Poking from an unmarked watery grave was part of a ship's hull. Hanselmann's team believed they'd found Satisfaction, and the rum company boasted about their partnership in a press release. Alas, their announcement came prematurely. As National Geographic elaborated, further investigation revealed that the ship had no connection to Morgan or his conquest. It was actually a Spanish merchant ship called Encarnación, which sank in 1681. The vessel provided vital information about shipbuilding in that period. For now Hanselmann will have to take solace in being the Mick Jagger of archaeology because he can't get no Satisfaction.

The Captain Morgan method for fixing hip dislocations

The Captain Morgan logo is a crimson-coated swashbuckler with one foot on a cask, or, depending how drunk you are, it could look like a blurry evil Santa Claus stepping on a rotund elf. However, at least one person took the alcoholic Rorschach test and saw a way to treat dislocated hips.

As NPR explained, when someone's thighbone pops out of their hip socket, it needs to be treated ASAP. Physicians commonly employ the Allis maneuver, which entails climbing onto the patient's gurney, straddling said patient, and bending the displaced leg to a 90-degree angle before applying force. But the awkwardness of the position can cause a physician to injure their back or fall off the gurney. And how embarrassing would it be if the doctor dislocated their own hip while hitting the floor?

Emergency medicine professor Gregory Hendey and his colleagues adopted a different approach in which the doctor stands on the floor and props up the patient's leg with an upraised knee. At some point Hendey saw a Captain Morgan commercial and realized they were standing like the captain. Thus the Captain Morgan method was born. It's unclear if the method is more effective than the Allis maneuver, but it certainly seems safer for the doctor. And according to Hendey, "Once they start using the Captain, they never go back."