The Magna Carta Is More Important Than You Probably Realize. Here's Why

Liberty. Justice. Fairness. Equality under the law. If anybody ever feels embarrassed handling these terms in a sincere way, feel free to imagine a society where such ideas never flowered. Imagine living under a government that believes it has to right to do to you whatever it wants, including theft and torture, and whose leaders are not held accountable to any legal measures because such measures don't exist. Imagine living in a nation where there is no recourse to right wrongs because there is no notion of "rights," and individuals can't act, speak, write, or even think freely without potential imprisonment or punishment. Now, have a look at 2022's Human Rights Index on Our World in Data, which aggregates civil rights, democratic processes, equal rights protection, freedom of expression, and more into overall scores. People worldwide live under such conditions every day.

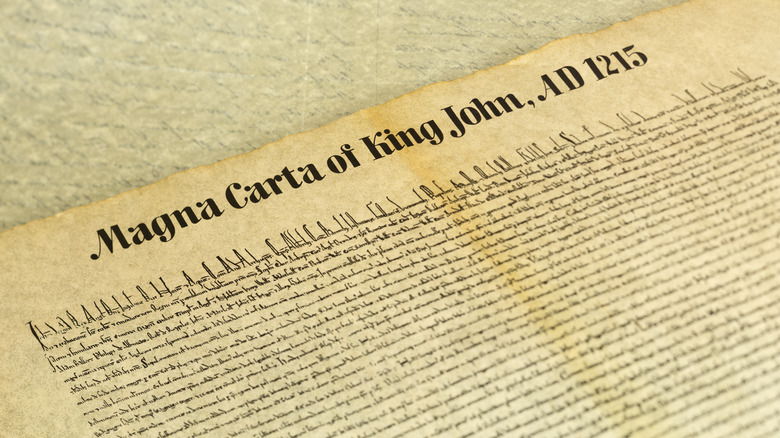

Is it an exaggeration to say that the Magna Carta — "The Great Charter" issued by England's King John in 1215 C.E. — forged the backbone of modern civil, legal, and judicial institutions that combat such an oppressive way of life? Not really. Is it an exaggeration to draw firm causal lines to all legislation in every subsequent Western nation over centuries of time? Certainly. But ultimately, as the British Library explains, the Magna Carta formed a precedent mirrored in the 1791 United States Bill of Rights, the 1948 United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the 1950 European Convention on Human Rights, and more.

Protection against tyranny

The National Archives recounts the drafting of the Magna Carta in 1215 C.E., when a full 40 noblemen confronted the king of England, John, with an ultimatum in the simple country field of Runnymede, England. They didn't draw swords, but rather strongarmed the tyrannical king into drafting and signing a document that protected them from him. The Magna Carta itself speaks to the cause of its drafting, per a 1297 C.E. translation from Middle English in the National Archives.

After a brief preamble thanking God, the Magna Carta describes protections for land and its people and property from destruction and usury, especially at times of inheritance. For example, protection for widows to ensure they receive their inheritance "immediately and without any difficulty." The Magna Carta also describes physical protection for all merchants traveling through England, prevents bailiffs and lords from "seize[ing] any land or rent for any debt," and requires that all legal disputes be held "in a certain fixed place" unrelated to the document's drafters.

All in all, the Magna Carta stipulates 63 such clauses related to civil rights. The most famous one reads, "No freeman is to be taken or imprisoned or disseised of his free tenement or of his liberties or free customs, or outlawed or exiled or in any way ruined, nor will we go against such a man or send against him save by lawful judgement of his peers or by the law of the land."

Embedded in the Fifth Amendment

The Magna Carta was the first document of its kind to safeguard what many of us in 20th- and 21st-century, post-Enlightenment societies take for granted. Looking back over its 63 clauses, it might seem bizarre that before 1215 C.E., there were no legal prescriptions in Western nations detailing specific instances of protection of property and person from the powerful to ensure fair and equal treatment under the law. Yes, laws were cataloged and written down thousands of years prior, as in the famed Code of Hammurabi, likely etched into stone during the reign of the Babylonian King Hammurabi from 1792 to 1750 B.C.E. Hammurabi's laws, however, were more standardized lists of punishments for specific crimes — not an outline of citizens' rights.

While there's no direct, 800-year-old legal lineage descended from the Magna Carta, the charter has served as a touchstone for later documents outlining similar principles; in this way, its spirit and purpose echo on. The National Archives explains that the United States Constitution and Bill of Rights, drafted by Englishmen familiar with their country's history, directly reflect the Magna Carta. This is especially true of the Fifth Amendment's "no person shall ... be deprived of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law." In 1941, as the National Archives quotes, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt said, "The democratic aspiration is no mere recent phase in human history ... It was written in the Magna Carta."

Upholding the rule of law

The Rule of Law Education Centre outlines how the Magna Carta influenced not only the United States' founding principles but also the United Nations. As the site succinctly states, the Magna Carta "began the tradition of respecting the law, limiting government power, providing access to justice and the protection of human rights." While the concept of "human rights" has roots in antiquity's reverence for humanity's special place within the world, the reader might be surprised to know that "human rights," as a legal construct, emerged only in the 18th and 19th centuries.

Hundreds of years earlier, England once again set the "rule of law" trend. Its 1628 Petition of Right restricted monarchical powers, the Habeas Corpus Act of 1679 ensured that those accused of crimes could challenge their case before a court, and the country's 1689 Bill of Rights — dubbed "the second Magna Carta" — outlined rules for free elections, the construction of parliamentary government, and free speech within that parliament. Then, as Amnesty International says, the 1776 U.S. Declaration of Independence roughly coincided with the 1789 French Declaration of Human Rights and Citizen, which cascaded onward into the abolition of slavery, women's suffrage, the rise of liberal democracies, and eventually the post-World War II creation of the United Nations.

In 1948, the United Nation's Universal Declaration of Human Rights drafter Eleanor Roosevelt called the document (via the Rule of Law Education Centre), "The international Magna Carta is for all men everywhere."

Abolished by the pope

Ironically, despite how the Magna Carta presaged modernity's fundamental civic protections, human rights, and the rule of law, the charter itself failed in its goals. After King John signed the document, he sought support from Pope Innocent III, who reached out with a papal bull from Italy and nullified the charter a mere 10 weeks after it was ratified.

As the British Library details, the pope called the charter "'shameful, demeaning, illegal and unjust" and stated that it should be "null and void of all validity for ever." As the British Library also says, the pope called the Magna Carta "harmful to royal rights and shameful to the English people." In other words, per Britannica, the Magna Carta "violated [the pope's] rights as feudal lord," aka diminished his power. The abolishment of the Magna Carta sent England into a civil war — the First Barons' War — that very year in 1216.

It took centuries, but the spirit of the Magna Carta won out. Those wishing to visit the spot where King John signed the charter can head to the quaint country hills of Runnymede, England, southwest of London, a curious location that the U.K.'s National Trust calls a mere "water-meadow and Thames flood plain." There's a little roofed memorial there with some stone benches and a nearby tearoom, perfect for contemplating the freedom that allows people to make such a journey and sit so quietly.