Why The Regency Era In Britain Was Such A Wild Time

In 1811, King George III of Great Britain and Ireland (pictured) was forced to relinquish his role as functioning sovereign after 50 years as the head of the British monarchy. He suffered for decades with unpredictable and manic bouts that in more recent times have been diagnosed as bipolar disorder and dementia. It was an unprecedented moment, in which the king's successor, the future King George IV, was installed as the prince regent in his father's stead after the passing of the "Care of King During his Illness, etc. Act 1811," granting him the power rule the kingdom until his father was well again — which of course never happened.

The period from 1811-1820 (and sometimes 1795-1837), which has become known as the Regency Era, has largely been depicted as consisting exclusively of stiffly dressed courtesans and nobility sharing awkward glances and occasionally pointed remarks thanks to the novels of Jane Austen and the countless costume dramas. However, more modern works such as "Bridgerton" are starting to embrace the lewd, permissive, and downright wild spirit of the age.

The excesses of George IV

It is arguable that the tone of society in the Regency Era in Great Britain was in many ways set by the prince regent himself, whose personal life and self-indulgent lifestyle contrasted markedly with that of his more sensible father, who before his illness took great pains to protect the sanctity of his sovereignty.

As the historian John Mullan of University College London, who worked as a consultant on "Bridgerton," notes in an article in the Daily Mail, the rampant sexual activity that the hit show portrays chimes very much with the life of the prince regent, who was noted for his excesses. George Augustus Frederick caused something of a stir in aristocratic circles thanks to his penchant for having affairs with married women, whose husbands found themselves in no position to object as a result of the future king's power.

George had reportedly already developed his hedonistic tastes by the time he was 17 and was known to overindulge in wine and getting into constant debt. Though his father attempted to keep him in check in his younger years, when his father fell ill and he became regent, he was free to indulge himself to his heart's content.

The Regency period was secretly decadent

Famously, on the face of things, the Regency Era was an age in which the British upper classes were obsessed with etiquette and good manners as ways of broadcasting one's moral correctitude and social standing. However, the truth is that despite that veneer of respectability, the period had a seedy underbelly just as all social eras do.

The streets of Regency London were often away with displays of affluence and taste, in which the rich of the city would be seen promenading in their finery or cutting through the throngs of the city's poor in opulent carriages. However, behind closed doors, the upper classes were not as upstanding as their public displays would suggest.

As well as widespread gambling at the capital's private member's clubs, pornography and sex clubs were hugely popular among aristocrats, as was the keeping of mistresses. In such circles, syphilis ran rife. It is arguable that the indulgences of the prince regent were representative of those that consumed many wealthy young Britons at the start of the 19th century. While he was singled out by the writer Leigh Hunt as arather immoral character, it may be fairer to identify the whole era as one of libertine behavior behind closed doors.

The Dawn of the Dandy

It is often said that people dressed better in the past, but never was top tier tailoring more in vogue than during the Regency Era, particularly among young men. The finest dressed of these were referred to as "dandies." And chief among the dandies was a man named Beau Brummell, a close friend of Prince George, who was famous throughout Europe for his impeccable dress sense and an enormous influence on the fashion of his day.

Thousands of rich young men began dressing in imitation of Brummell during the Regency period, in a style described as particular but understated. However, in contrast to this fashion movement was the "fop," who dressed extravagantly for show, according to Jennifer Kloester's "Georgette Heyer's Regency World." Kloester claims that being a true dandy also meant being witty and charming in social situations, as well as somewhat aloof.

Brummell himself was a complex figure, who became the embodiment of vanity at the same time as he drew admiration from across the British aristocracy. After falling out with Prince George, he eventually fell into debt, and in his later years was forced to escape to France, where he died in an asylum.

Hard drug use was widespread

The recreational use of drugs is often thought of as a modern phenomenon, one which came of age during the 1950s and 1960s with the development of new psychoactive substances such as LSD. However, Regency Britain was awash with drugs — though they were rarely talked about in the same moralist tones as they often are today.

In the early 1800s, people from all walks of life consumed a variety of drugs that are now considered dangerous and illegal but which were often available from the local pharmacy. A typical 19th-century medicine cabinet would contain laudanum, an opium and alcohol infusion used for pain relief and to combat various illnesses — despite the concoction causing countless deaths and being a known suicide method. Other substances that today are considered poisonous, such as chloroform, were also used to treat various ailments.

Thomas De Quincy's "Confessions of an English Opium Eater," first published in 1821, set the template for drug literature, outlining for the first time the addictive nature of recreational drug use and changing the way people thought about the medicines they consumed.

The Romantics caused a revolution of their own

Before the Regency Era, English poetry was written in an arch and epic tone and focused on high concepts. However, poets such as William Wordsworth and Samuel Taylor Coleridge believed that poetry should be written using the language of everyday people and deal with real societal issues. Both were part of an early generation of Romantics who, through works such as the dual-authored "Lyrical Ballads," first published in 1802, revolutionized the art of poetry.

The Romantics saw their role as that of guiding society toward freedom through the imagination, with the second-generation poet Percy Bysshe Shelley proclaiming that poets "are the unacknowledged legislators of the world" in his "A Defence of Poetry." The Romantics were also rebellious in their personal lives, with a willingness to break societal norms particularly when it came to sex, and to use drugs such as opium to stimulate the imagination and generate poetic images.

The slave trade that made Britain rich finally came to an end

From 1662 onward Britain was instrumental in establishing the transatlantic slave trade, trafficking over 3 million people from West Africa and forcing them into slavery in America. The slave trade generated a great deal of wealth for Britain, but eventually, a movement emerged to put an end to the heinous practice.

In the late 1700s, abolitionists led by the Parliamentarian William Wilberforce (pictured) formed the Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade in London, which gradually raised opposition to slavery in the capital and beyond. Through their work, Parliament outlawed the slave trade in 1807.

However, slavery was also rife throughout the British Empire, and though the slave trade was technically outlawed before the Regency Era, work continued to put an end to slavery in all British territories. The period saw a marked change in the way average Britons thought about slavery, with more and more agreeing it was inhumane and a violation of human rights. However, it was only in 1834 that Britain finally banned slavery as a practice with the passing of the Slavery Abolition Act.

A new dance caused a scandal

The Regency Era may have been radical in its politics and unconventional in its private pastimes, but with etiquette reigning supreme during these years public displays such as dances could often be a breeding ground for scandal. The waltz, for example, first came to Britain in the 1810s having been performed traditionally in Germany and Austria for hundreds of years. But while the dance may seem stiff and inoffensive today, when many Regency Britons first caught sight of the waltz it caused a commotion — and not in a good way.

To people in the Regency Era, the "German waltz" was somewhat scandalous because it encouraged dancers of the opposite sex to hold each other closely, whereas established dances typically called for some space between dancers for the sake of decorum. It is also important to note that for generations, ballroom dances in Britain typically saw people of the opposite sex lining up together to dance in file; with the arrival of the waltz came turning, spinning, and a new relentless tempo that many older aristocrats objected to. It was a watershed moment, but while many objected to the new dance as a gateway to loose morals, it became all the rage and remained popular throughout the 19th century.

The Luddites were challenging industry

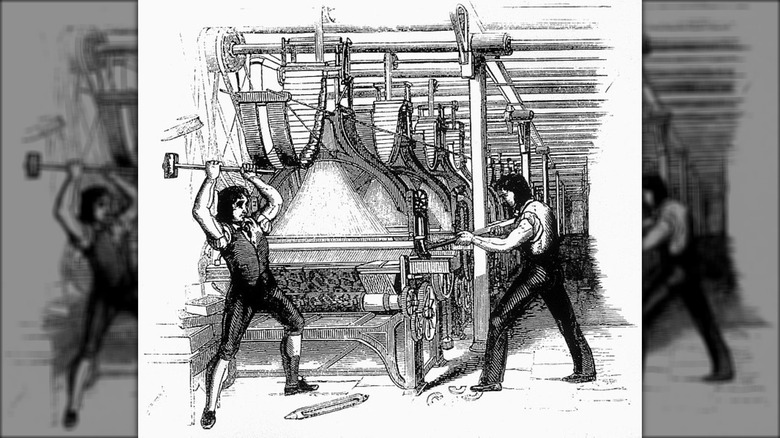

The word "Luddite" is sometimes used today to describe people who oppose or are slow to adapt to new technologies such as cell phones and the internet, but originally the word had a very specific historical meaning that was found during the Regency Era. In the 1810s, the Luddites were a group of protestors originating in the county of Nottinghamshire who sought political reform to control the disruptive effects of new industrial technology that was taking away their livelihoods.

Said to be led by a figure named Ned Ludd — who in actual fact was fictional — the Luddites favored direct violent action in the face of progress, breaking into factories to destroy cutting-edge machines in the hope of saving jobs in industries such as weaving and knitting. The group's activities were largely curtailed in 1812, however, as machine breaking became a capital offense, leading to the hanging of 17 men in 1813.

The government was at risk of attack

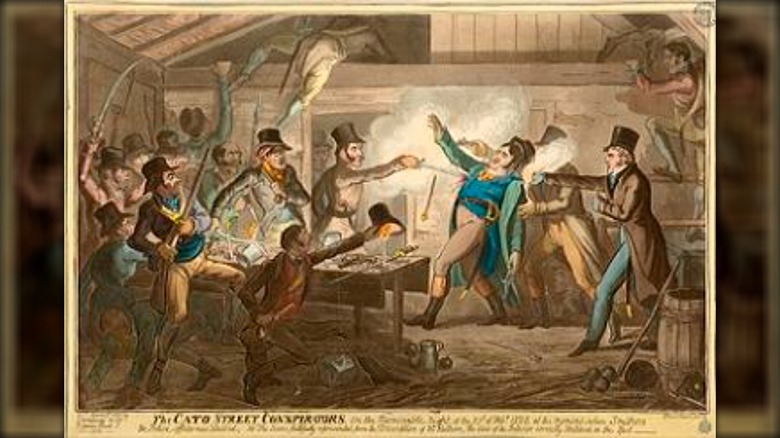

When people think of threats to the British Parliament, many recall the famous events of the Gunpowder Plot, in which a group of oppressed Catholics led by Robert Catesby and Guy Fawkes conspired to blow up the Houses of Parliament and murder King James I in 1605. However, there was another major attack on British democracy during the Regency period which, though little remembered today, may have been just as destructive.

The Cato Street Conspiracy was largely the brainchild of Arthur Thistlewood, who, along with a group of sympathizers, planned to murder a restaurant full of prominent members of the British government on February 23, 1820 — and ultimately spark a revolution. Thistlewood's plan was discovered, however, and he and four others were hanged for high treason. How close the government came to being wiped out deeply shocked British society when news of the plot broke.

Lord Byron encapsulated the spirit of the age

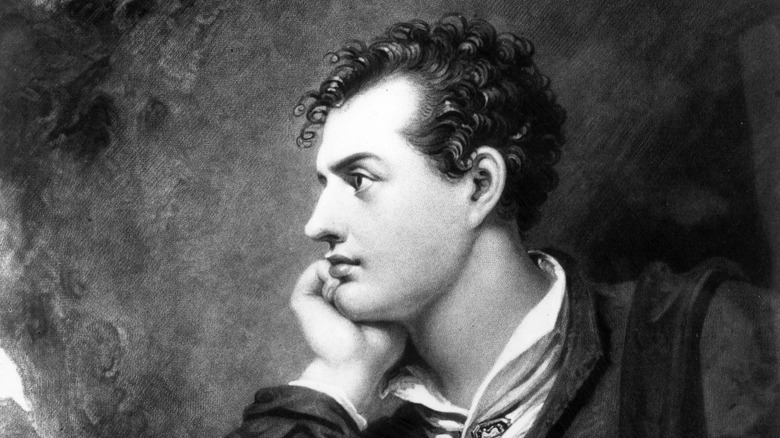

The poet Lord Byron was a prominent figure among the second wave of Romantic poets, whose works combining social satire and romance became some of the bestselling literature of the era.

But Byron was also a definitive Regency figure for the scandal he attracted. Though not exactly a dandy, he was famously handsome and charismatic — and notoriously known for his string of affairs, including a rumored liaison with his own half-sister. Though he went into self-exile when the charges against him seemingly became too much, he remained a hero to much of the reading public. His last act immortalized himself by joining the Greek War of Independence, during which he fell ill and died. The only part of the Byron story that doesn't chime with the overall spirit of the Regency Era is that he hated the waltz and famously published an anonymous poem deriding the dance, which he thought of as vulgar and — somewhat ironically — corrupting.

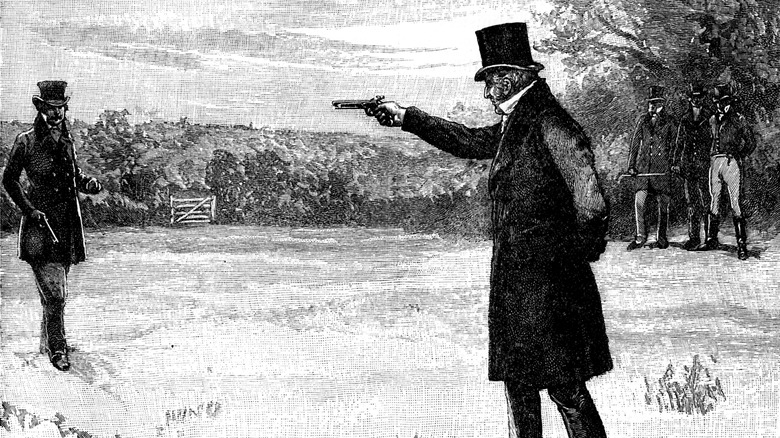

Even the Prime Minister was duelling

Dueling with swords had long been a traditional way of settling disputes in Britain, and though it became illegal to duel as early as 1819, it remained a common practice until the middle of the 19th century. It is believed around 1,000 duels were fought in Britain between 1785 and 1845, most of which would have taken place between members of the aristocracy, though some middle-class professions also turned to dueling to resolve arguments or perceived slights to a person's honor.

And despite the British system of government being exalted as a model for democracy, politicians occasionally resorted to dueling when they found themselves at a heated political impasse. One famous duel fought during the period involved the prime minister himself, Arthur Wellesley, the duke of Wellington, a famous British Army general who defeated Napoleon Bonaparte at the Battle of Waterloo.

Wellesley's premiership was short and heated, with a proposed Catholic Relief Bill that sought to end the oppression of Catholics throughout the British Isles proving particularly controversial. When another member of parliament, the Protestant earl of Winchilsea, accused Wellesley of encouraging the spread of Catholicism, especially in Parliament, the offended prime minister challenged Winchilsea to a duel. The pair met with pistols on London's Battersea Fields, though the duel ended with the men unharmed and Wellington satisfied that the insult to him had been settled, per an 1829 news report in The Guardian.