These Final Messages From Sinking Ships Are Haunting

While there's something beautiful and picturesque about sailing along in a boat, when you think about it, it's actually a pretty scary experience. After all, you're surrounded by water, and if something goes wrong it could result in horrible tragedy. In order to keep that from happening, ships have had ways to communicate with other vessels or people on shore since the telegraph in the late 1800s. Since then, the technology has just gotten more advanced, and these days, there are many ways to guarantee someone hears your cries if the boat you're on needs assistance.

However, sometimes that assistance doesn't come, or at least doesn't get there fast enough to save everyone. When sinking ships result in deaths, the messages sent at their moment of peril become the tragic last known words of those on board.

MV Sewol ferry

On April 16, 2014, the MV Sewol ferry in South Korea capsized (pictured). Those who survived recounted a traumatic and hectic experience as the boat started sinking. "The rescue wasn't done well. We were wearing life jackets. We had time,” one passenger told the AP (via BBC News). "If people had jumped into the water ... they could have been rescued. But we were told not to go out." Another survivor told a local South Korean TV station, "The announcement told us that we should stay still, but the ship was already sinking and there were a lot of students who did not get out of the ship." In the end, 304 people died.

Since there were hundreds of students on board, and there was a bit of time before the boat sank, many sent panicked text messages to family members. One mother told AFP (via the BBC) that her daughter wrote, "We're putting on our life vests. They're telling us to wait and stay put, so we're waiting ... I can see a helicopter." Another mother who didn't know what was happening to her child was confused when she received a text saying, "This might be the last chance to say I love you."

After these and other texts were reported widely, CNN said that some of them, especially ones that claimed to be written after the boat sank, were called into question. However, it is clear many were genuine, from before those on board were in the water.

Bourbon Rhode

On September 17, 2019, the Bourbon Rhode left port in the Canary Islands and headed for Guyana. Eight days later, it became clear the ship was going to sail right through a Category 3 hurricane, but it didn't change course, despite already having obvious leaks from unfinished repairs. The next day, disaster struck. The ship sank, and only three of the 14 crew were saved in a rescue mission (pictured). Seven bodies were never recovered.

About an hour after the first distress signal, the ship sent out a message that it was flooding: "We have no more engine, they are all down. All crew muster, ready and on standby" (via Maritime Executive). An hour after that, the Bourbon Rhode's last message reported "life rafts not possible to launch, very rough seas, swell 10 {meters] or more."

According to an interim report compiled by the government of Luxembourg, the disaster was avoidable, since it was obvious before the ship sailed that it was not seaworthy. In fact, one of the people originally hired to crew the vessel walked off the job because the condition of the Bourbon Rhode was so clearly unacceptable. While the person hired to replace that one did get on board, they also noted the issues with the ship. The fact that most of the crew was inexperienced would not have helped when things started to go wrong.

Gulf Livestock 1

The ship Gulf Livestock 1 had 5,910 living creatures on board when it set sail from New Zealand on August 14, 2020: 43 humans and the rest cows. Heading for China on September 2, the ship hit a typhoon. When Emily Hastings sent a WhatsApp message to her brother, 27-year-old crewmember William Mainprize, saying that the weather situation was scaring her, Mainprize tried to reassure her, writing, "Should be fine — we're a big boat." He even added the wave and rowboat emojis. However, she told SKY News that while he seemed fine when speaking to her, "He had also messaged friends saying that the boat was floating sideways and taking in water and that he was really frightened."

Mainprize and 40 others died. According to the two survivors who were rescued (pictured), a massive wave swamped the ship, resulting in engine failure. After the sinking, the tragedy of the families was made worse when the search was called off after only one body was located.

While the loss of 41 humans is infinitely more tragic, there were people concerned for the cows that died alongside them. "These cows should never have been at sea," animal rights organization SAFE told SKY News. They had a point, since this wasn't the first time thousands of animals had died while being transported by ship, and the government of New Zealand had promised to do something about the issue only the year before.

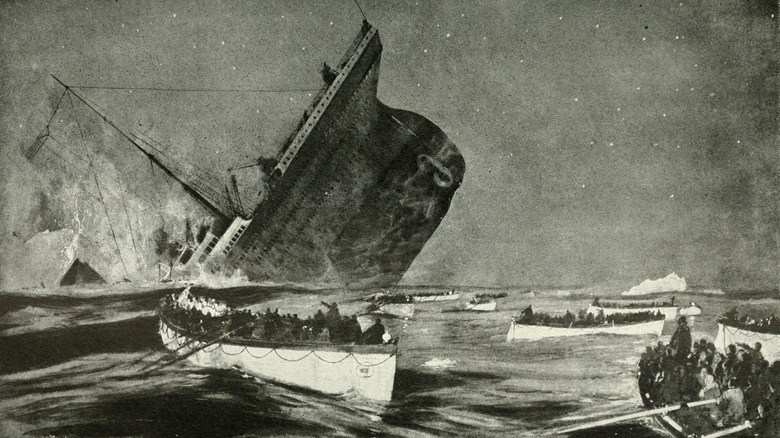

Titanic

There is no sinking more famous than that of the oceanliner Titanic on April 15, 1912. The ship that was said to be unsinkable hit an iceberg in the middle of the North Atlantic on its maiden voyage. An estimated 1,500 died, while 706 were rescued.

When disaster struck, the ship's telegraph operators begged for assistance. "Come at once. We have struck a berg. It's a CQD, old man," the Titanic called to another ship, the Carpathia. Other messages sent as the situation deteriorated grew more desperate: "We have struck an iceberg and sinking by the head," "We are putting passengers off in small boats. Women and children in boats. Cannot last much longer. Losing power," and "Come quick. Engine room nearly full." When one boat that was too far away to offer any help tried to join the panicked telegraph conversation, the Titanic replied, "You fool ... keep out" (via BBC News).

One thing many people know about the messages sent from the stricken Titanic was that they used "SOS." The letter combination (which doesn't actually stand for any words or phrase) was a relatively new way to indicate distress and not many telegraph operators used it yet, instead sticking with the older "CQD." One of the ship's telegraph operators who survived, Harold Bride, told The New York Times that he joked darkly with his boss Jack Phillips that he should use SOS because "It's the new call and it may be your last chance to send it." Phillips went down with the ship.

Migrant dinghy

In the early morning of December 14, 2022, the captain of a fishing boat in the middle of the English Channel woke up to panicked screams. What he saw when he got on deck was shocking. "It was like something out of a second world war movie, there were people in the water everywhere, screaming," he told SKY News (via The Independent). He and his crew spent the next few hours pulling men, women, and children onto their boat.

While Americans might be most familiar with the political arguments over immigration at their country's southern border, Europe also sees desperate migrants take extreme risks to make it to various countries there. While getting to the United States requires crossing the desert, across the Atlantic, it often requires crossing the Mediterranean or the English Channel. The boats used are usually overloaded or less-than-seaworthy, which means that sometimes they sink and many people die.

In this instance, it was a small boat with 47 migrants onboard that had set sail from France in the middle of the night. As the boat began to take on water, one of the passengers left a voice message for a French migrant charity. "We are on the boat and we have a problem. Please help. We have children and a family on the boat," he said, according to iNews. "Water is coming in the boat and we don't have anything ... Please help me, bro." Four migrants died, with others hospitalized in critical condition.

Oryong 501

The Oryong 501 was a fishing boat sailing in the Bering Sea on December 1, 2014, when the crew realized the ship was taking on water. At first, it seemed like a temporary setback, as they were able to borrow a pump from a passing ship and remove most of it. But it quickly became clear this was a much bigger problem and that their lives were in serious danger.

The Korean media outlet Hankyoreh listened to the final radio messages from the ship. The captain, Kim Gye-hwan, was speaking to Lee Yang-woo, the captain of yet another nearby ship, who was also a former co-worker and friend of a decade. "I thought we had balanced the ship, but then it suddenly leaned to the left. I've received orders to evacuate the ship," Kim told Lee. Then: "Yang-woo, I wanted to say goodbye before the end." His fellow captain tried to motivate Kim to keep going, imploring him, "Don't say that! Get all of the crew off the ship safely and then make sure that you make it out alive as well." But Kim knew the inevitable was imminent. His last words were, "All the lights inside the ship are off. After what I've done to the crew, how could I let myself survive?"

While family members of the crew held out hope they might somehow have survived, rescuers were only able to save seven people. Of the remaining 53 crewmembers, 26 of their bodies were never recovered.

Pacific

In 1861, someone in Scotland picked up a bottle on the beach and found a message inside, forwarding it to The New York Times. That year, The New York Times published the tragic missive: "On board the Pacific, from L'pool to N. York. Ship going down. (Great) confusion on board. Icebergs around us on every side. I know I cannot escape. I write the cause of our loss, that friends may not live in suspense. The finder of this will please get it published, WM. GRAHAM."

The newspaper also explained how they had looked into the mystery of where this final message came from. Apparently, there were several ships named Pacific that it could be referring to, but after contacting shipping companies and checking passenger lists for the name of the man who wrote it, the reporters determined it was probably a boat that left England for New York on January 23, 1856, but never arrived.

Of course, at the time, people did notice an entire ship had just disappeared in the Atlantic, but this was not as uncommon as one might hope. Until the message in the bottle was discovered, no one had any idea what had become of the Pacific (pictured). According to "Mysteries and Sea Monsters: Thrilling Tales of the Sea (Vol.4)," by Graham Faiella, there were 186 people onboard, all of whom must have perished in the sinking.

Ross Cleveland

On February 4, 1968, while caught in terrible weather off Iceland, the fishing boat Ross Cleveland was hit by a huge wave and tipped onto its side. The Hull-based British crew of the ship tried to get out safely, but the skipper seemed to know it was a longshot, sending a last radio message to his cousin, Len Whur: "I am going over. We are laying over. Help us, Len. I am going over. Give my love and the crew's love to the wives and families ..." (via Fishing News).

Only one of the men on board survived. According to the Hull Daily Mail, Harry Eddom was working on the masts when disaster struck, so he was wearing extremely warm and wind-resistant clothes already. The rest of the crew didn't have time to dress for the weather, to the point some were in short-sleeved shirts. Two of those men saved Eddom's life by pulling him into a lifeboat with them, where he then had to watch them freeze to death and drift with their bodies for hours.

This was not the first tragedy to hit the Hull fishing community: It was the third boat to sink in a month. In total, there were 58 victims of what became known as the Triple Trawler Disaster. In response, Lillian Bilocca (pictured), the mother of a sailor who was not on any of the doomed ships, organized other women connected to the fishing industry and pushed for change, including basic safety measures.

SS Princess Sophia

The Alaska State Library records that around the turn of the 20th century, the state's coastline saw 87 boats wreck and sink in less than 40 years. However, not all of them led to great tragedy, and in at least one instance there were no casualties. Sadly, this was far from the case in the sinking of the SS Princess Sophia.

While the steamship was technically only allowed to have 250 people onboard, this was regularly ignored, since 500 could fit comfortably. When it departed from Skagway on October 23, 1918, there were 343 passengers and 21 crewmembers aboard; it was particularly busy since winter was coming and many people were heading further south before it got too cold. However, the ship found itself in a snowstorm and, blinded, ended up off course. Hours after departing, in the early hours of October 24, the Princess Sophia rammed straight into a reef (pictured).

The ship had been in similar situations before, according to the Anchorage Daily News, and since water wasn't coming in, it just stayed there, waiting for the storm to pass so those on board could be rescued. But after being stuck for 40 hours, the ship shifted and sank. As the ship radioed rescuers "For God's sake hurry," one passenger had already written to his fiance telling her "the boat may go to pieces" and that he'd written his will that morning, "leaving everything to you, my own true love" (via CBC News). Everyone on board died except a dog named Tommy.

SS Beaverford

The SS Beaverford was never supposed to be a warship, but desperate times called for desperate measures. When World War II started, the cargo ship owned by the Canadian Pacific Railway was requisitioned by the United Kingdom government. While it was still used to transport goods, it was also fitted with some big guns, just in case. Sixteen journeys across the Atlantic with important war cargo were uneventful. The 17th was not.

The Beaverford left Canada on October 28, 1940, sailing to England. About a week later, the convoy the ship was part of ran into a German battleship, the Admiral Scheer, whose captain had been told to attack cargo ships in order to disrupt England's war effort. At first, the Beaverford wasn't part of the ensuing battle, instead holding back and radioing what was happening to other ships. Eventually, the German ship's guns trained on it, though, and the Beaverford sustained serious damage. However, it did not skink quickly, thanks largely in part to the fact it was transporting a lot of buoyant lumber. But it was clear there was no way out.

The captain of the German ship heard the final message from the ship it was attacking: "It is our turn now. So long. The Captain and Crew of the SS Beaverford" (via the Warfare History Network). At that point, the Admiral Scheer fired its most destructive shot yet, so large that the impact of the torpedo lifted the front of the Beaverford out of the water before it sank, killing all 77 on board.