Tragic Details About First Lady Dolley Madison's Life

First Lady Dolley Madison (1768-1849) is an American heroine, known from popular portraits depicting the legendary feat of running out of the White House carrying George Washington's portrait as the British were burning Washington, D.C. Although that scene is a myth, she did help save the portrait while personally carrying out a handful of founding documents, such as the Declaration of Independence.

The first lady's actions on that day in adverse times were not particularly surprising, though. Despite growing up in a well-to-do family and marrying the wealthy planter and future president James Madison, she had her share of hardships throughout her life that taught her how to stand on her own two feet.

Dolley faced numerous financial and personal tragedies (many of them interrelated) throughout her 81-year life. From nearly descending into poverty thanks to her father's business failures to losing her husband and son on the same day, her early life was among the hardest she ever faced. Her surviving son would later be a constant financial thorn in her side as he drank and gambled his life away. Here are the many tragedies of one of America's most famous and influential first ladies.

She watched her father spiral into depression

In 1783, John Payne, Dolley Madison's father, decided to move his family from Virginia to Philadelphia – perhaps to be around other members of the Society of Friends (a.k.a. the Quakers), who had founded the city. There, he opened a laundry starch business.

Although Philadelphia had done relatively well economically during the early republic, America's first decade of full independence saw a downturn that has been compared to the Great Depression – including a credit crunch, money shortage, and a 30% reduction of GDP. In this climate, the business failed by 1789.

The 22-year-old Dolley Madison left virtually no letters from her early life, but one can assume life was tough. Between 1789 and 1792 – the date of John Payne's death – Dolley watched her father spiral into depression. Worst of all, the Quakers considered financial stability a condition of membership and a mark of godliness, so they expelled the deeply-indebted John Payne from the Society. Ironically, he had previously enforced the exact rules he was kicked out for violating.

John Payne's failure nearly put his family into penury, forcing his wife to open a boarding house for extra money. He also got Dolley married to a wealthy lawyer named John Todd. It is unclear whether Dolley wanted the marriage. Biographer Richard Cote argues that Dolley married John Todd for love, as well as stability. Historian Catherine Allgor, however, noted that Dolley had refused Todd before, suggesting the marriage was initially one of convenience that Dolley might have otherwise rejected. Although all seemed well with the marriage, the economic hardships did not end there.

She lost her husband and son to yellow fever on the same day

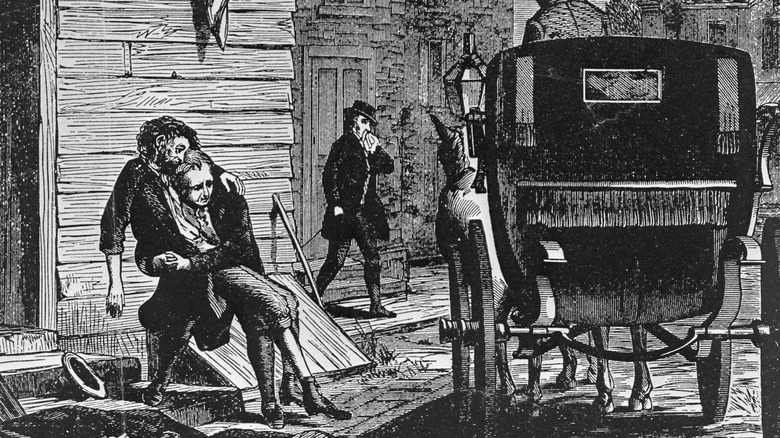

Dolley Madison's first marriage was a happy one. She bore her husband John Todd two children: John Payne Todd and William Temple Todd. The latter was born in 1793 – the same year a deadly yellow fever epidemic struck Philadelphia, then the nation's capital. The city's wealthy, including several founding fathers, fled. Dolley, who had just given birth, was in no condition to travel and had to be carried out. John, however, stayed, setting the stage for Dolley's quadruple family tragedy.

The first casualty of the family was Dolley's mother-in-law, who died on October 11, 1793, according to one of Dolley's letters (via Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography) to her brother-in-law, James Todd. She expressed her fear that she would "soon follow her to the Cold Inclosure of the Grave." Another letter from James informed her of her father-in-law's death and of the "dread prospect" that her husband would soon follow. John Todd died within two weeks. The hardest blow, however, was the death of her infant son William, who died the on same day as his father.

Dolley was so inconsolable that her mother had to write on her grief-stricken daughter's behalf to John Todd's nurse. Her daughter, she wrote, "[couldn't] write her self to Day," having "the same day Consined her Dear husband & her little babe to the silent grave." Because she was "very unwell" and facing financial ruin, Dolley's mother begged the maid to send any money John Todd might have left behind.

She lost part of the estate to her brother-in-law

After Dolley Madison's mother requested money from Dolley's first husband John Todd's estate, Dolley ran into a problem with her brother-in-law, James Todd. He not only wanted his father's estate (which he was entitled to) but his brother's too, according to the Pennsylvania Magazine for History and Biography. Dolley, however, needed her inheritance to avoid poverty.

For Dolley, it was also personal. In a letter to her brother-in-law, she wrote that the biggest tragedy of the inheritance battle was James' attempt to sell her late husband's library – "Books from which he [John Todd] wished his Child [John Payne Todd] improved, [and should] remain sacred." She preferred to "feel the pinching hand of Poverty before [she would dispose] of them."

By 1794, James was dragging his feet. Facing financial ruin again, Dolley hired a lawyer and asked James politely once more. She followed it up with a threat: if Todd did not give her the inheritance, she would "demand" the money – a threat to sue – "[a]s [she could not] wait [his] return from the proposed Excursion without material Injury to [her] Affair."

As the suit was being settled, Dolley received a lifeline through her marriage to James Madison, who lent his power and influence to resolve the problem. In 1795, she finally got the money owed to her – five $1,900 checks (each equivalent to over $46,000 today) from the sale of Todd family properties. This marked the end of the tragedies and economic hardships of her early life, although other issues would arise during her marriage to the future president.

She was also kicked out of the Society of Friends

Dolley Madison's marriage to James Madison in 1794 jeopardized her membership in the Society of Friends (Quakers). Richard Cote's "Strength and Honor" notes that Quakers were supposed to marry within the Society. But late-18th century Philadelphia faced an influx of single men due to its status as the federal capital. Quaker women had more options to marry out of the faith. But the Society also expelled people who married out, so with each out-marriage, Quaker numbers and influence fell in the city they had founded.

Dolley's marriage to James posed an additional problem: not only was he Episcopalian – he also owned slaves. Quakers, meanwhile, had been among American slavery's earliest opponents. For Dolley, a nearly life-long member, leaving was not an easy choice. But she chose love and was kicked out of the Society.

Although Dolley had some friends who were expelled, it hurt to see those who remained Quakers abandon her. Even before the marriage, a former suitor and friend wrote that "[her] Enemies had already opened their Mouths to Censure and condemn [her]." Women even "averted their eyes when they saw her on the street."

The marriage and expulsion sent her into new, unfamiliar social circles. In Quaker circles, everything had been simple, and the people were humble. James Madison, however, ran in "sink-or-swim" elite circles – a world she was not used to. But despite the abrupt change, she managed to adapt, showing the social grace and charm that made her famous and beloved as a first lady.

Her second marriage was childless

By 1800, Dolley Madison's sisters had mostly started having children. Dolley and James Madison, however, were childless – and it troubled them, per Richard Cote's "Strength and Honor." Their problems became the talk of their social circles, as rumors swirled about James' potential infertility.

By 1809, it seemed the couple had finally conceived. In a letter to Thomas Jefferson, Joseph Dougherty wrote that Dolley, by then the first lady, "[could not] abide the smell of the paint: that [might have been] on account of her pregnancy." This letter is the only attestation of a pregnancy in the Madison marriage. Because it is only mentioned once, and since no child was ever born, it is possible that Dolley suffered a miscarriage, a stillbirth, or something along those lines.

Ultimately, it is unclear whose fertility was compromised. Yellow fever and her difficult second pregnancy could theoretically have impacted Dolley's fertility, although yellow fever usually damages the kidneys and liver. A study from the American Urological Association, however, noted that James Madison was an epileptic. The neurological disorder is correlated with lower fertility or even sterility, suggesting that he was the one unable to have children. He was not alone in that regard, either. George Washington and Andrew Jackson were also likely sterile from smallpox. Regardless, Dolley compensated for her childlessness by doting on her son John Payne Todd, her nieces and nephews, and children of the couple's friends.

She lost her favorite sister to marriage

Dolley's closest relative and friend was her sister Anna, whom she called her "sister-child" due to the 11-year gap between them. Anna lived with her, basically as her daughter, and was a constant feature in Dolley's daily social life.

In 1804, Anna married Congressman Richard Cutts – a day which Dolley described as "one of the greatest griefs of [her] life," as recorded by her niece Lucia Cutts Beverly in "The Letters and Memoirs of Dolley Madison." Nevertheless, she did everything to turn her sister's wedding into a "scene of great gayety." But then Anna left for Maine, meaning Dolley only got to see her when Richard's congressional duties brought him to Washington.

The closeness of their relationship showed in Dolley's letter sent to Anna just days after her wedding. She called Anna a "ray of brightness on [her] sombre prospects," noting how much she missed her, but was happy to hear that she was doing well and constantly thinking of her.

Anna's departure likely affected Dolley more than usual due to a mix of other events. In her letter to her sister, Dolley noted that Thomas Jefferson's daughter Maria, who was also Dolley's friend, had recently died. Her son John Payne, meanwhile, "continue[d] weak and sick," while Aaron Burr had shot Alexander Hamilton to death in the duel. Washington, D.C. was mostly empty when Congress was not in session. Being lonely, isolated, and surrounded by death, it is obvious why losing her sister – her main source of comfort – even just to marriage, would have affected her so much.

She spent six bedridden months away from her husband

On June 4, 1805, Dolley Madison wrote to her sister Anna that she had injured her knee and spent ten days in bed, unable to walk or put any weight on it. Dolley was suffering from an ulcerated knee. She feared she "would never walk again," suggesting amputation was a possibility.

Dolley's knee and mental well-being gradually worsened. A letter to Anna from her niece Lucia Cutts Beverly's collection "The Letters and Memoirs of Dolley Madison," dated to July 8, 1805, had her still bedridden and alone in a deserted Washington, D.C. – Congress was presumably not in session. Despite her problems she had committed to helping Thomas Jefferson's granddaughter Virginia do her wedding shopping.

When Dolley knee problem began, her husband, then-Secretary of State James Madison, begged her to see Philadelphia Dr. James Physic for treatment. She initially refused because she "dread[ed] the separation," but eventually assented, writing to Anna from Philadelphia that she had been well received and assured of recovery.

Despite the high standard of care she received, Dolley's letters make it clear that the months of separation from her husband were not easy. When James Madison faced weather problems traveling to Washington, she wrote that she was "unable to sleep, from anxiety for [him] ... Detention, cold, and accident seem[ed] to menace him." She also started having dreams about her husband "unable to move, from riding so far and so fast." It was not until mid-November that she was released. But not before she received a special treat: a visit from her sister Anna.

Her husband's death left her all alone

Dolley Madison's marriage to James Madison was a happy one, but by the 1830s, the former president was crippled from rheumatism and unable to walk. For Dolley, it meant an end to their social life to nurse him. She "never [left her] husband more than a few minutes at a time, and [did] not [leave] the inclosure around [her] house" for eight months. She hoped he would live until Independence Day, but he refused all medication and died on June 28, 1836.

Dolley was crushed. According to her niece Lucia Cutts Beverly's "Memoirs and letters of Dolley Madison" the former first lady suffered from "utter loneliness in a separation from one with whom she had lived so happily for forty years." But she was kept busy anyway as famous Americans of all stripes wrote to her expressing their condolences over the death of her husband. And although she made sure to answer them all individually, she could not hide her grief.

In her letter to President Andrew Jackson, she expressed that her "only solace" from President Madison's death was Americans' high regard for him, along with the condolences she received praising him. In a letter to her brother-in-inlaw Richard Cutts (husband of her favorite sister, Anna), however, her loneliness showed. She begged him to come visit her and bring all his children, whom she considered as her own, suggesting that staying at home taking care of her husband and his death had left her isolated and needing family support.

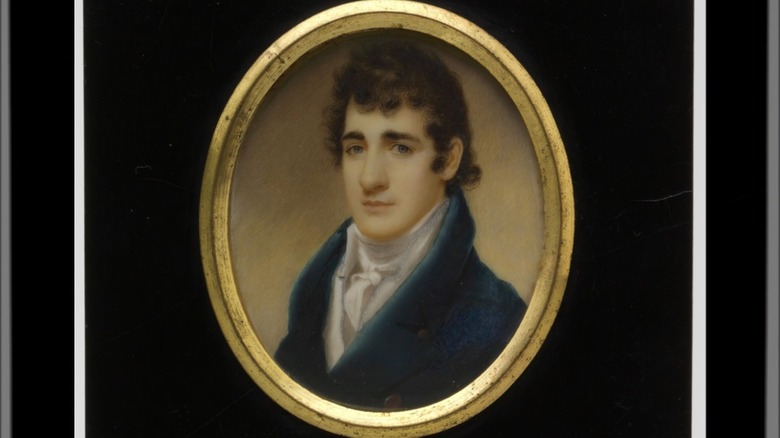

Her only surviving son used her for money

Dolley Madison's only surviving child was John Payne Todd (above), who in his early years, was described as a handsome, young image of his father. Unfortunately, he gravitated towards a wasteful lifestyle (pg. 581) of womanizing, excessive drinking, and getting into debt – so much so, his relatives knew him as "the miserable creature." His mother, however, adored him and covered for him at every opportunity – even when he abused her love to get money.

Payne's lifestyle began with a European adventure of drinking, gambling, and partying rather than studying – his mother's original purpose for the trip. James Madsion quietly paid all the debts he accrued there. But after 1836 – the year of James Madison's death – John, who had become an alcoholic, was reliant on his mother for money.

Her letters attest to their one-sided relationship. In an 1845 letter concerning a slave, Dolley added that she wanted her son to acknowledge the receipt of $30 she had sent him – presumably to get him out of his latest financial hole. In another letter from 1848 (pg. 512), she sent him $50 for some clothes. She wrote another letter shortly after (pg. 514) begging him to acknowledge the money.

The pattern here suggests that John often wrote to his mother when he needed her, but failed to follow through on basic gratitude. He never offered financial assistance when she needed it, and may have even embezzled money from business transactions he did on her behalf – business she had entrusted him as a way of helping him get back on his feet.

Her son caused her to lose almost everything

After President James Madion's death in 1836, Dolley Madison found herself in fresh distress as her son John Payne Todd's habits drained her personal finances. The first lady's grandnephew, James Madison Cutts, later wrote (pg. 515) that he "remember[d] her best in the last years of her life, when [he] often looked into her face and with a child's instinct knew ... she was poor."

To pay her son's debts, she reluctantly sold the president's old plantation at Montpelier in 1844 – a place she had nothing but fond memories of. As she progressively unloaded other assets, she was forced to rely on the charity of friends and relatives in Washington — people such as Cutts.

Before her death, Congress threw her a lifeline. Seeing the damage Todd was doing to America's beloved former first lady, Congress voted to buy James Madison's personal papers for $25,000 (~$705,000 today). She would get $5,000 up front to cover her debts, while the rest went into a trust to protect it from Todd.

After Dolley's death, her material legacy mostly went up in smoke. Her son auctioned off much of her material estate as collateral for debts, including her wardrobe and sentimental possessions such as paintings. Her niece, Anna Payne Causten, bought much of it to keep the sentimental items in the family. By 1944, only a small bit of memorabilia was left, locked in a trunk – the only pieces that survived her great-grand nephew's selloff to cover his expenses during the Great Depression.