The History Of Benjamin Franklin's Cherished Walking Stick (And Where You'll Find It Today)

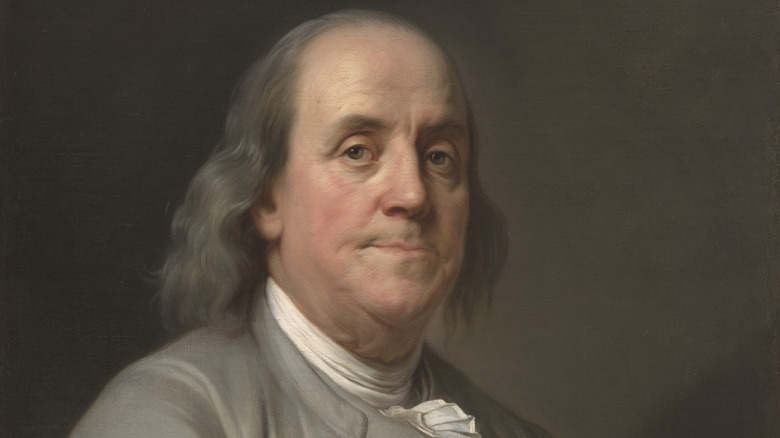

Not many men in history have as famous a personal iconography as Benjamin Franklin. Even someone with minimal knowledge of the American Revolution and the Founding Fathers could probably give you an accurate picture of the man. It would be the one you see on the $100 bill: Bald on top but with flowing, graying hair, a full moon face with eyes hooded by wisdom, and a smart suit in the colonial fashion.

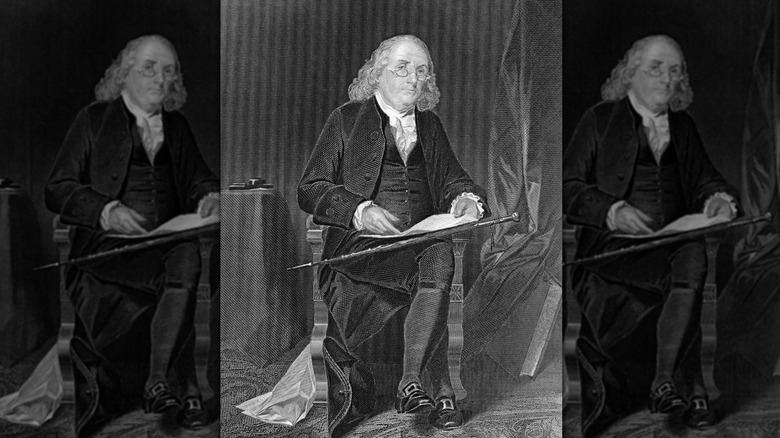

What that popular image leaves out are the health troubles that plagued Franklin in the later years of his life. Per the Philadelphia Inquirer, from middle age on he suffered from gout, an inflammatory condition that only worsened with time. It was a condition Franklin readily acknowledged. He even wrote a lengthy tongue-in-cheek dialogue between himself and the gout, with the malady chastising him for indulging in habits that exacerbated it (per Walter Isaacson's "Benjamin Franklin: An American Life"). There wasn't much Franklin could do other than laugh at it — there was no cure, and the foot pain caused by the gout made it increasingly difficult for him to move around.

By his final years, Franklin needed a wheelchair. But he also made use of walking sticks. And one of them, a handsome gold-topped cane, is an item in the collection of the National Museum of American History (per the Smithsonian). Before finding a home there, the stick traveled a long way — through France, Pennsylvania, and the hands of another founding father.

The stick was a gift from a French countess

Per Wondrium Daily, the walking stick in the Smithsonian's collection was described by Benjamin Franklin himself as "my fine crab-tree walking stick, with a gold head curiously wrought in the form of the cap of liberty." It wasn't the first walking aid Franklin ever had, and in some ways it could be seen as less elaborate than the bamboo cane with a hollow joint filled with cooking oil that Franklin used in experiments and play (per The Kitchen in the Cabinet). But the gold-topped stick carried with it a symbolic value — it was gifted to Franklin from a friend who aided in the cause of American independence.

That friend was the Countess of Forbach, Maria Anne. She was just one of the many in French society who were charmed by Franklin when he came there as the American commissioner. Per David McCullough's "John Adams," the French revered Franklin as a scientist and adored him for embodying their image of Americans as simple rustics. He happily played along, dressing in simple fashion and going about in a fur cap. Maria Anna — a full-throated supporter of the American cause whose nephew and sons served in the war — grew close to Franklin personally during his time in France.

After the Battle of Yorktown, Franklin and the countess celebrated in Paris with the Marquis de Lafayette. It was at that celebration that Maria Anna gave Franklin his gold-capped stick. The "cap of liberty" on its top was modeled after Franklin's own fur hat.

Franklin left the cane to George Washington

According to Wondrium Daily, Benjamin Franklin viewed the walking stick given to him in France as a prized possession. He seemed to consider it invested with a certain degree of symbolism, too. In his last will and testament, drafted in 1789, he left the stick to one of his fellow founding fathers: "To my friend, and the friend of mankind, General Washington. If it were a sceptre, he has merited it, and it would become it."

George Washington had treasured objects of historic importance of his own. Per the New York Post, he had a collection of five swords. In his own will, he left one each to his five nephews, with the express command that they only be used in the defense of the United States. By 1831, one of those swords and Franklin's cane were in the hands of Washington's great-nephew, Samuel T. Washington. He gave both to the U.S. government in 1843 with this wish: "Let the sword of the hero and the staff of the philosopher go together."

The Smithsonian brought the stick into its collection in 1995. As of November 2023, it isn't on public display in the National Museum of American History, but images can be found online.