This Is Who Inherited George Washington's Estate After He Died

The Virginia planter society of colonial America was one steeped in debt. The land-rich, cash-poor de facto aristocracy enjoyed great influence over society, but per Santa Clara University, heavy borrowing to maintain their lifestyle left them indebted and vulnerable. This financially perilous system endured after the Revolutionary War, and those Founding Fathers from the Virginia planter class were steeped in it. Debt cost Thomas Jefferson's heirs almost his entire estate (per Monticello), and George Washington was nearly broke when he was elected president (per The Daily Beast). But unlike Jefferson, he wasn't so deep in the red that his home, land, and property had to be auctioned off instead of passed on.

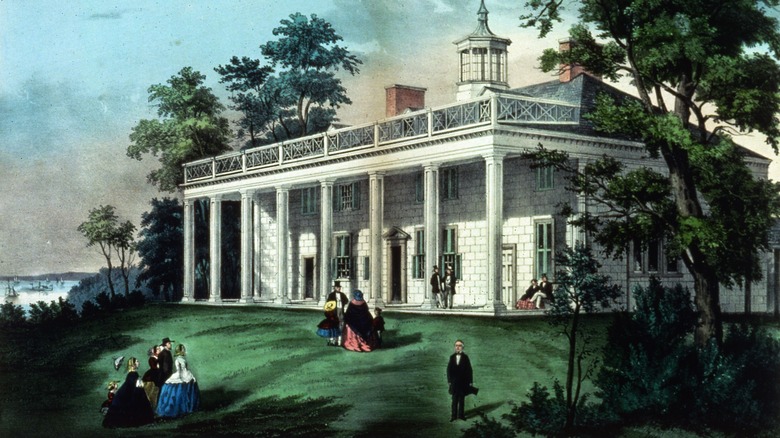

By his will, available through the National Archives, Washington called for what debts he had left — "of which there are but few, and none of magnitude" — to be quickly settled. This left a considerable estate, made up of land and property in four states, stocks, and personal effects. The bulk of this was left to Washington's wife, Martha, for her personal use and profit. She became the owner of Mount Vernon after Washington's death, and a plot of land in the city of Alexandria was singled out to remain with her and her heirs in perpetuity.

Sections of Washington's estate were carved out for relatives and beneficiaries

The first item in George Washington's will specified that the whole estate was to go to his wife Martha "except such parts thereof as are specifically disposed of hereafter." Specific bequeaths were made to the trustees of the Alexandria Academy (Washington's shares in the city bank, for the construction of a school to provide free education to orphans) and the Liberty Hall Academy (his shares in the James River Company, for the academy's benefit). Washington also called for his shares in the Potomac Company to form an endowment to a future university in Washington, D.C. (it was ultimately never built).

Having no children of his own, Washington was close with his many nieces and nephews and with Martha's children from a previous marriage (per Slate). In his will, he forgave debts owed him by the estates of his brother and brother-in-law and forgave educational loans to his nephews. He also arranged for a tract of land leased to his brother Samuel to be left to the heirs of Samuel's deceased son; granted a lot in Manchester, Virginia to his nephew William Augustine Washington; and carved out a section of the Mount Vernon estate for his nephew Bushrod, who later inherited it in whole.

Washington's will also gave his family members certain personal effects. Each of his five nephews was given a sword, though the blades came with an express command that they not be unsheathed — except in the cause of self-defense or the defense of America.

Washington arranged for his enslaved people to be freed

After his bequeath to his wife, the second item in George Washington's will concerned the fate of the 123 enslaved people he owned. A slaveholder since the age of 11, Washington grew increasingly troubled by the practice over the course of his life, even as the population of enslaved people in Mount Vernon reached 317. By the time of his death, Washington had privately expressed a desire to see gradual emancipation through legislation, and he considered his will an act of leadership by example.

Manumission, however, was legally complicated. Aside from the 123 people Washington personally held in bondage, most in Mount Vernon were held by Martha Washington after her first husband, Daniel Custis, died without a will. On her death, these enslaved people reverted to the Custis family, and there was no legal means for the Washingtons to free them. Many of those held by Washington had intermarried with their dower counterparts, and as Washington did not wish to separate families, this added another difficulty.

Ultimately, Washington willed that his enslaved people were to be freed after his wife's death (she chose to free them early, possibly out of fear for her life). He also arranged for the care of any too old or infirm to work and for orphaned slaves to be taught to read, write, and do math. The one man Washington freed immediately was William Lee, who had loyally followed and attended the military officer throughout the Revolutionary War.