The Significance Of Stars In Different Spiritual Practices Explained

Before modern astronomy, humans attempted to explain stars. They realized stars regularly rose and set at more or less the same time. They were also guides, as travelers and sailors could orient themselves with them. Finally, certain stars always seemed to coincide with important natural events — in some cases of literal world-ending importance.

Given their importance and mystery, stars are the subjects of some of the most beautiful and vivid symbologies in virtually every religious tradition on the planet. They have often been equated with divine beings, their myths, and the natural phenomena they controlled. In religions such as Christianity, pagan beliefs around stars were re-interpreted to explain the roles of figures like Jesus and the Virgin Mary, while Muslims viewed their regularity as a sure sign of God's existence.

Although the basics of star symbolism are common to most religions, the small nuances and culture-specific imagery of star myths and their symbologies give each tradition its unique beauty. Here are some from around the world.

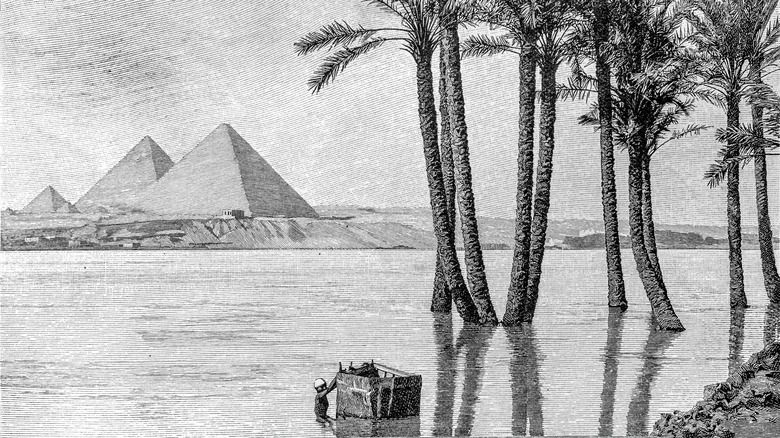

In Egyptian religion, the Dog Star announced the Nile flood

Ancient Egypt's lifeblood was the Nile River, whose yearly flood dumped silt that Egyptian farmers used to grow their crops. The flood was, however, also a religious phenomenon aligned with the heliacal rising of the Sirius. The ancient Egyptians believed that Sirius – commonly known as the "Dog Star" – was the goddess Sopdet, who around July 21st, ascended over the horizon to the foremost place in the heavens as the brightest star of all. That marked the beginning of the inundation season of the Egyptian calendar and the new year.

The Nile flood was caused by Ethiopian summer monsoon rains, which swelled the Nile's tributaries, causing it to burst its banks further north in Egypt. Not knowing that, the Egyptians developed multiple myths developed to explain the Nile flood's timing with the rising of Sirius. One myth posits that Sirius was a personification of the goddess Isis mourning the murder of her husband, Osiris. She cried so many tears that she caused the Nile to flood. Upper Egyptians believed that the rising of Sirius was the signal for the god of the inundation – an androgynous fertility deity named Hapi – to emerge and bring his blessings upon Egypt.

Classical Greek religion believed they were deified beings

The classical Greek word for a star constellation is "Katasterismos," which translates to something like "star-legend." In this case, the legend derives from the ancient Greeks believing the constellations represented mythical figures deified in the stars. The reasons for deification varied: Some were there by virtue of being celestial deities. The Pleiades, for example – the seven daughters of Atlas and the nymph Pleione – enjoyed a place in the stars by default. However, one of them shone less brightly than her sisters, because she loved a human rather than a god.

Other constellations were deified as favors from the gods, such as the crab Cancer. According to one version from Greek mythology, Hera placed it among the stars for distracting the hero Hercules while he was fighting the hydra. Although Hercules ended the crab's mortal life, its willingness to die for Juno meant that it lives on to the present day, immortalized in the sky.

Sometimes, the gods created constellations to impart lessons to mortals. Take the story of Orion the hunter. He believed himself the best hunter ever, claiming he could kill any of Earth's creations. An angry Earth sent Scorpion to kill him, and Zeus immortalized the beast as the constellation Scorpio to warn men of the dangers of excessive pride. Zeus also made Orion a constellation, turning him into a deity worshiped among the Boeotians.

The Babylonians believed they were gods and their messages

Ancient Babylonian religion was intricately tied to the planets and stars – often considered one and the same. According to "Mesopotamian Astrology," celestial bodies and constellations were associated with certain divinities. For instance, the chief god of Babylon, Marduk, was associated with the planet Jupiter. Since the celestial bodies were deities unto themselves, they could communicate with mortal rulers and their priests.

Gods could communicate with mortals directly via their planets, or by manipulating other astral bodies, such as stars, to get their message across. Priests would observe the bodies and write omens using the following formula: if celestial body x does y, then z will happen. The omens could be good or bad. A good omen, which naturally brought blessings upon the royal house, was a sign of divine favor, while a bad omen could be a sign of an upset god. Usually, omens were not set in stone, and evidence from the Babylonian texts suggests that rulers could stave off misfortune, either through scapegoating someone else or bettering their conduct towards the gods. This practice has partially survived in modern times as astrology.

Celestial movements dictated so much of Babylonian religion that they formed the basis of the Babylonian calendar, according to the Proceedings of the International Astronomical Union. Festivals, processions, clothing of deities, and sacrifices were all celebrated according to celestial movements, while even medical treatments were prescribed according to which zodiac constellation was most visible in the sky — something scholars call "astral medicine."

The Inca believed they sustained the dark cloud animal gods

The Inca religious relationship with stars went beyond one-to-one correlations with deities. The Inca departed from other traditional understandings, viewing most stars and their constellations as inanimate objects in the sky instead of deities. There were exceptions, such as the Pleiades constellation, which was considered a "huaca" – an animate spiritual body of sorts that was worshiped.

The inanimate stars, which formed the Milky Way Galaxy, were a highway to heaven called the Mayu River, the source of all water on planet Earth. The deities that lived within and along the banks of this celestial star river, in the forms of various animals familiar to the Incas, were represented by the starless dark patches of the galaxy, and are hence known as "dark" or "cloud" constellations.

At least two cloud constellations were definitively identified with deities: the serpent, known in Quechua as Mach'acuay, and the mother llama, known as Urcuchillay. The Inca worshiped Mach'acuay because he controlled all snakes on Earth. If Mach'acuay was happy, he would keep venomous snakes away. Urcuchillay, the mother llama, received sacrifices in the form of alpacas and llamas from Andean pastoralists, hoping for her favor and prosperity. So although the Incas did not always worship the stars themselves, the Incas' conception of the world — including some of their deities – could not exist without them.

Mexica religion dictated certain stars had to appear to prevent the end of the world

The Mexica of Central Mexico – better known as the Aztecs – believed the end of the world could occur at the end of any 52-year cycle, unleashing the stars – now converted into monsters – upon a humanity plunged into darkness by the death of the sun. In response, the Mexica state (the Aztec Empire) conducted the New Fire Ceremony to renew the world and stave off such horrific possibilities.

The entire success of the ceremony depended on stars — in this case, the appearance of the Pleiades. According to Ancient Mesoamerica, on the final night of the 52-year cycle, the Mexica would extinguish all fires in the Valley of Mexico. They would also clean out their houses, throw away clothing, tools, statues of deities, and anything associated with the previous cycle. The priests of Tenochtitlan (Mexico City) would climb the mountain of Huixachtlan and wait for the Pleiades' rise. If the constellation appeared and passed the zenith, earthly life would continue for another five decades.

After the Pleiades appearance, it was time to renew the world through human sacrifice and new fire. Therefore, the priests would light a fire on the first sacrificial victim, before killing them and then sacrificing other victims. That initial fire was passed around to light up the temples of Tenochtitlan and eventually the hearths and houses of the Valley of Mexico's inhabitants. According to Spanish Friar Bernardino de Sahagun, some even scorched themselves in the fires.

In Catholicism, the Virgin Mary is crowned with stars

Stars hold special significance in Roman Catholicism due to their association with the Virgin Mary, who is often referred to as a star herself. Two Marian titles are "Star of the Sea" and the "Morning Star."

As "Star of the Sea," Mary is the patroness of sailors, and, in a way, of all faithful: Life is a voyage full of storms that tempt Catholics away from righteousness. Mary acts as the North Star, the ever-present, fixed point that guides the faithful towards Jesus Christ. Her title of "Morning Star" follows similar logic, as she announces to the world, at the darkest hour of the dawn, the coming of the light, Jesus.

Anyone who has seen a Marian statue has likely noticed that the Virgin Mary sometimes wears a crown of 12 stars. This is from Revelation 12, which depicts a woman "clothed with the sun, with the moon under her feet, and on her head a crown of twelve stars." Catholicism teaches that the woman is Mary, whose crown simultaneously represents the 12 tribes of Israel and the 12 Apostles — one for each tribe. The crown identifies Mary as the queen of the "New Israel" founded by Jesus Christ (the Catholic Church), which is carried on by the descendants of the 12 tribes – the Apostles. As mother of the Church, Mary is also the Queen Mother of the Apostles, and by extension, the spiritual mother of all Catholics, circling back to her role as a star-guide.

In Christianity, the pentagram symbolizes Jesus, not Satan

Across Christianity, stars are associated with the person of Jesus Christ. The association appears from the beginning of Jesus' life, as the Gospel of Matthew tells that the star of Bethlehem informed the Magi of Jesus' birth, following it to his manger. Even so, it might be surprising for some to find out that Jesus Christ is associated with the Pentagram – the five-pointed star today commonly linked with satanists.

Before it became a part of satanic symbology, the pentagram represented the star of Bethlehem, or Jesus' wounds at the crucifixion — one per point of the star. Common throughout churches in the Middle Ages, the Church of Latter-Day Saints continues this tradition of pentagram decorations on its temples in the present day.

Jesus is also depicted as a bringer of light, more specifically, "the root and offspring of David, the bright morning star," per Revelation 22:16. The title "morning star," however, can also be translated as "Lucifer," or "lightbringer" — a title popularly associated with Satan. However, this originates from a lack of context in the King James Bible's translation of Isaiah 14:12. Here, the word "lucifer" actually refers to the king of Babylon, not to Satan. So, although Lucifer may be the name of Satan in popular imagination, symbolized by the five-pointed star, there is nothing in Christianity's texts themselves that suggest either the title or the symbol refer to anyone other than Christ.

In Judaism, the hexagram is the symbol of the faith

The six-pointed Star of David is Judaism's most recognizable symbol, but its origins are unclear. Jewish legend says it was King David's personal coat of arms – hence the name star's alternative name, "the shield of David." When Jewish rebel Simon Bar Kokhba fought the Romans in A.D. 132, Rabbi Akiva ben Josef called him the "son of the star," meaning he was a descendant of King David, and a potential messiah worthy of carrying his ancestor's shield to restore the Jewish people to their kingdom.

Although the star appears in Jewish contexts as early as the fourth century A.D., its pan-Jewish significance is relatively recent. The Jews of Prague chose it as their standard when Emperor Charles IV granted them permission to carry one in the 1300s, and it marked off the Vienna Jewish Ghetto from the rest of the city in the 17th century. But it was the World Zionist Congress that adopted it as the symbol of global Judaism in 1897.

Because the symbol's purely Jewish associations are so recent, its exact symbolism is still debated. Jewish mysticism believes that it represents God's six male attributes in union with a seventh feminine life force, represented as the empty space between the two triangles. Regardless of the significance, it is central to Jewish identity today and is emblazoned on the Israeli flag.

Islam believes they are signs of God's existence

Islam views stars as a manifestation of God's glory and existence. Sura 37 of the Quran, as-Saffat, says that Allah created the stars to beautify the night sky and provide a barrier of protection from demonic entities trying to get to heaven. As-Saffat says that when these devils attempt to eavesdrop on the angels, they "are pelted from every side [and] fiercely driven away." A hadith (saying) of the Prophet Muhammad clarifies these verses, explaining that when Allah commands the angels to do something, demons called jinn try to eavesdrop on them. Thus, Allah pelts them with shooting stars before they can hear the commands, pervert them, and transmit them to their earthly allies, who use them to sow unbelief. Bosnian theologian Omer Spahic identifies these allies primarily with occult practitioners.

Finally, stars are guides. Sura al-An'am states that Allah created the stars as a natural road map for travelers, both on land and sea. This divine map in the heavens is one of the signs of all-powerful Allah's existence.

This literal symbolism behind stars extends to the metaphorical realm. Just as the stars guide travelers, the Muslim faithful are supposed to in effect become radiant stars themselves. That way, they serve as guides to the next generation of Muslims, taking them through the turbulent voyage that is life and keeping them on the righteous path in accordance with Allah's precepts.

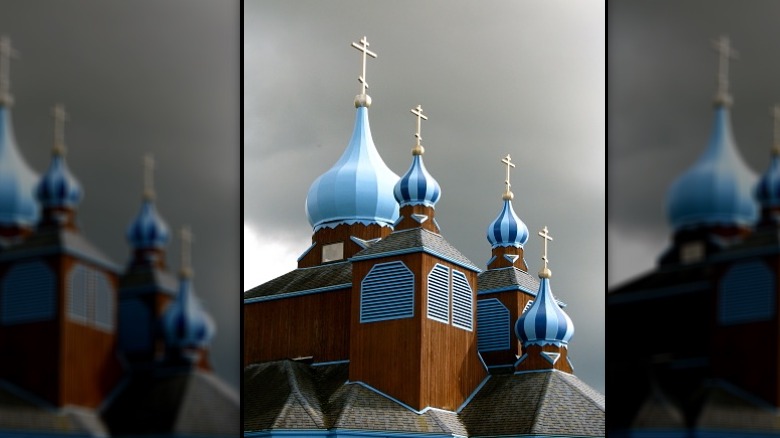

Eastern Orthodoxy, stars spread Christmas cheer

Eastern Orthodoxy, like other Christian groups, places a central importance on the star of Bethlehem in Christmas celebrations. Instead of simply incorporating it into architecture, however, Orthodox faithful of the Carpathians have historically brought the star back to life with a tradition called "starring." The idea is to place the faithful in the shoes of the Magi, who, in the Gospel of Matthew, followed the star of Bethlehem to adore the infant Jesus.

During a "starring" procession, the faithful march behind large star-shaped pinwheels, traveling from house to house and village to village, following the star that announces the birth of Christ to the world. As they march, they sing, stopping at different houses to pick up more marchers and donations for the local parish church. This Eastern European tradition eventually made its way to the Americas via Russian colonization of Alaska.

The Alaskan version of "starring" is called "Slaaviq," which appears to be a native Alaskan rendering of the Russian word "slava," meaning "glory." True to form, the celebrations have incorporated plenty of Alaska Native traditions, including carols in native languages, primarily Yup'ik. The procession begins from the church, goes to the cemetery and the parish house, and from there, splits up into multiple smaller processions to spread Christmas cheer to as many people as possible. If the procession blesses someone's house by visiting it, that person then offers food to the marchers — sometimes even a full-scale feast.

In Zoroastrianism, stars are the difference between life and death

Zoroastrianism, a native religion of Iran, associates some stars with angels called the yaazatas, who include Satavaesa, Vanant, and Tishtrya. The latter angel, who is associated with Sirius — the Dog Star — occupies an important place in the Zoroastrian faith because he controls the world's water, believed to be contained in the mythical sea of Vourukasha.

The myth of Tishtrya recounts that he fought the Zoroastrian water demon Apaosa over the period from the rising of the star Sirius until his final fall triumph against the demon. He prepared for battle for thirty days, covering the time from the July rising of Sirius to the late summer/early fall. He would then lose a three-day battle, but eventually triumph over the demon, with additional worship and sacrifice from men on earth to release the waters of Vourukasha. That coincided with the fall rains in Iran, which were dispersed with the help of another star angel – Satavaesa. Thus, in Zoroastrian Iran, without stars, there was no water. Without water, there was no life.

Zoroastrian astral beliefs have been preserved in the modern Iranian calendar. The fourth Iranian month is called Tir, a contraction of the deity's name, and which corresponds to June 21-July 21. The rising of Sirius is the hottest time of the year, so it is no coincidence that the story of Tishtrya called for men to make many sacrifices to him, so he could have the strength to fight Apaosa and give the earth some rain.

In Buddhism, the star goddess is the universal savior

The goal of a Buddhist is to attain Nirvana, a state of enlightenment in which all negative earthly passions and emotions are eliminated. Among the patron deities of enlightenment was the goddess Tara, who, as an astral deity, fulfilled a number of functions on the road to enlightenment.

According to "The Tara Tantra," the name "Tara" literally means "star." Unsurprisingly, she was originally the patron of travelers and sailors, sometimes portrayed as a star guide in the night sky, or as a woman in a boat who rescued drowning sailors and brought them to shore. Tibetan Buddhism ran with this symbolism to turn her from a patron and savior of lost travelers to the universal sailor of humanity.

Buddhism, like many other religions, sees life as a chaotic journey, ideally towards Nirvana. Seekers of enlightenment face numerous storms, particularly internal ones, that throw them off the path towards Nirvana, afflicting faithful with negative emotions and ignorance. Tara, as the literal star goddess, became the inner star that dispelled darkness inside men, to keep them from stumbling off the road to Nirvana.