How Adolf Hitler Really Came To Power In Germany

With the resurgence of far-right political factions in recent years, concerned parties have sounded warnings drawn from the recent past. Horror stories of what happened when extremist groups either seized power or were swept into it by the people. A perennial example is the rise of Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party in 1930s Germany. Bernie Sanders raised the specter of Nazism to The Christian Science Monitor in 2015, and Hilary Clinton did the same on "The View" in 2023 (via ABC News). Both included the ominous comment that Hitler had been legally elected in 1932.

That the Nazis were given power by the German electorate is a popular simplification of the history of fascism, one that posits a wave of middle- and working-class resentments elevating Hitler and company to power (per The Atlantic). It's a view not entirely unfounded. But it's one that doesn't account for the peculiarities of German politics in the 1930s, the state and system of the Weimar Republic, the tactics of the Nazis, and what surviving records show about their supporters. The whole picture looks less like a despot swept in by a frenzy of disgruntled voters and more like an opportunistic gaming of politics and media — backed up by violence. Read on for the story of how Adolf Hitler really came into power.

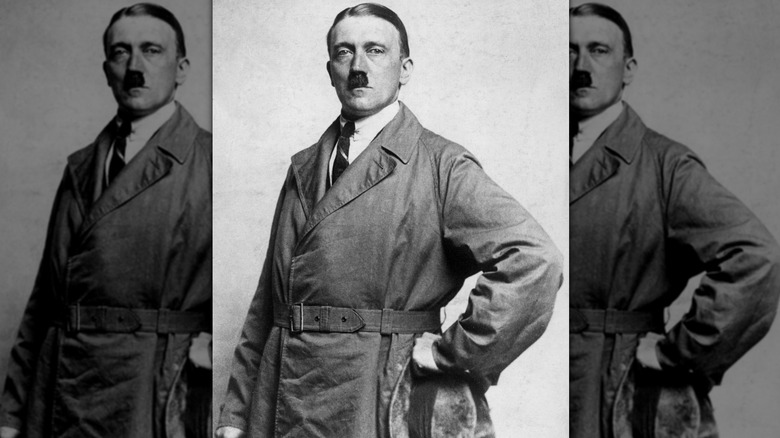

Hitler took control of the Nazi party over 10 years before becoming chancellor

The National Socialist German Workers' Party of Weimar Germany was long waiting for a chance at real power. Per Britannica, it began as the German Workers' Party in 1919, changing to its more infamous name within a year. Adolf Hitler was an integral force within the party almost from its inception. He was a valued asset thanks to his charismatic speeches, his theatrical rallies, and his 25-point program that repudiated the Treaty of Versailles and combined fierce nationalism with antisemitism. According to The Weiner Holocaust Library, he was considered so important to the party's viability that its leaders dropped their previous opposition to Hitler's demands for total control when he briefly resigned. By 1921, he was the dictatorial chairman of the Nazi Party.

Under Hitler, the Nazis built up their paramilitary arm, the Sturmabteilung (SA), and they attempted a coup with the ill-fated Beer Hall Putsch of 1923. Though the revolt was quickly put down, legal maneuvering kept Hitler from appearing before the supreme court, and his five-year sentence for treason was suspended within months. Upon his release, Hitler worked to build up party membership. He also redirected its energies to obtaining power through the existing system rather than through overt revolution.

The Nazis built up their base throughout the 1920s, reaching 180,000 registered members by the decade's end. Through publications and public speeches, Hitler continued to refine the party's platform. And new organizational schemes allowed the Nazis to infiltrate different professions and better generate political support.

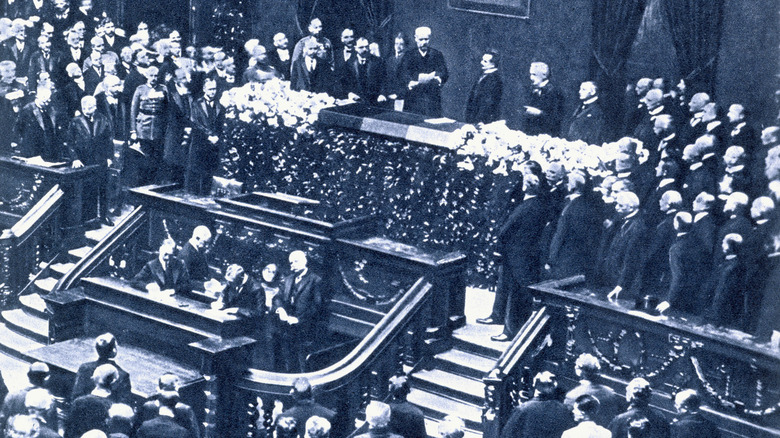

The Weimar Republic was an unstable parliamentary system

The legal system the Nazis sought to infiltrate after the Beer Hall Putsch has become popularly known as the Weimar Republic. The constitution behind the republic, drawn up as World War I ended, was spearheaded by moderate Social Democratic Party leader Friedrich Ebert. According to Britannica, the politician would have preferred a constitutional monarchy but was pushed into a republic by extremist elements. The new government he drew up was a parliamentary system with extensive powers vested in the Reichstag, voting rights extended to anyone over 20, and proportional representation given to political parties.

The republic, however, was insufficiently radical for more extreme socialist and communist parties, and many in the economic sector were opposed to democracy. Per the BBC, revolts from the left and the right plagued the republic almost from its inception. Hyperinflation, the worst in postwar Europe, was also an ongoing concern in the early 1920s, and many of the German people deemed the government's acceptance of the Treaty of Versailles an unforgivable offense. Though accepting the treaty was the least bad of the options available at the end of World War I, the punitive measures of the treaty left Germany severely weakened and exacerbated the economic situation. On the far right especially, the treaty was used as a rallying cry against the government — one the Nazis eagerly exploited.

It's been widely reported, by the BBC and others, that Weimar's proportional representation further weakened the republic. Under that system, no stable majority ever emerged to form a strong government. Such proportional representation allowed smaller parties, like the Nazis, to get a foothold in the Reichstag.

The Great Depression and the Russian Revolution boosted the Nazis' popularity

Per The Weiner Holocaust Library, the Nazi Party's organization, propaganda, and intimidation through the SA didn't immediately translate into electoral success. In 1928, the Nazis won only 12 seats in the Reichstag — less than 3% of the vote. But the Wall Street Crash of 1929 badly affected Germany, dependent as it was on American investment. Collapsing employment and soaring poverty reignited unrest in the country — and gave Adolf Hitler and the Nazis an opening. They won over 18% of the vote in the 1930 elections and almost 38% in 1932, earning them 230 seats in the Reichstag.

Per The Atlantic, an analysis of the 1932 election shows that Hitler's electoral support came largely from rural, historically Protestant areas. The Nazis built up support by undercutting rival parties, bussing in additional supporters to inflate the size of their rallies, and appealing to fears of communism. After all, the Russian Revolution was still a fresh source of anxiety throughout Europe, and the conservative, upper-class segment of the German population saw in Hitler and the Nazis a useful bulwark against such developments at home.

While support for the Nazis was concentrated in the upper class, a certain percentage of nearly all groups of voters was swayed by the party. The traditional parties of the left, right, and center failed to clearly articulate an alternative. They also remained at loggerheads with one another, making the Nazis the largest bloc in the Reichstag despite being collectively outnumbered.

The media handled Hitler with kid gloves

As part of his reorganization of the Nazi party after the Beer Hall Putsch, Adolf Hitler tried to reign in the SA. Per The Weiner Holocaust Library, the brownshirts, largely made up of former soldiers, were left to run wild in their intimidation efforts against other political parties. Hitler appointed a new leader, Franz von Salomon, to instill discipline. But the changes he made were largely of tactics and image, not mission, and the SA remained a violent tool of Nazism.

The violence of the SA, which ranged from implicit intimidation to political assassination, was hardly a secret. But the German press never treated Hitler and the Nazis as a serious threat. According to The Atlantic, Weimar newspapers painted the party and its leader as decisive and well-meaning rapscallions rather than terrorists. Papers of all political stripes offered mild praise for Nazism's stated intentions to improve German fortunes, sometimes with mild rebuke for their tactics. This ginger treatment meant that much of the SA's violence went unreported, or else was mischaracterized.

Not that the German press never reported on violence — if not wholly in thrall to Nazi propaganda, newspapers did echo the party's concerns about the threat of communism. Ironically, the Kommunistische Partei (KPD), Germany's communist party, had begun to moderate by 1932. But the damage had been done by then. Traditional conservative parties, which had initially been opposed to Nazism, began to cooperate with its adherents, dismissing or feigning ignorance of their violent behavior just as the media had.

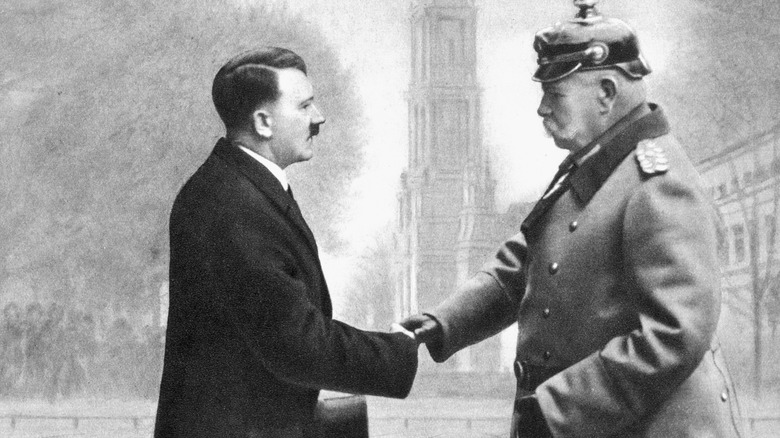

Presidential powers let Hitler become chancellor

Though the Nazi Party was the single largest bloc in the Reichstag after the 1932 elections, it was well short of a majority and even lost votes in a snap election later that same year (per The Washington Post). The snap election was called on account of the inability of parties to form a working coalition — something that had proved elusive in the Reichstag since the onset of the Great Depression. To function, sitting chancellor Heinrich Brüning began to rely on a quirk of the Weimar constitution: Article 48.

Per the BBC, Article 48 granted the German president extensive powers to act without parliamentary authority in an emergency, a poorly defined term. The article allowed Brüning — in cooperation with President Paul von Hindenburg — to enact policy despite heated opposition from both the Nazis and the communists. But by 1932, his position was untenable. His replacement, Franz von Papen, proved unpopular. Yet despite Papen's shortcomings and the Nazis' electoral success, Hindenburg refused to appoint Adolf Hitler chancellor. Papen and the circle of advisors around the president all sought an alternative coalition — one that involved the Nazis as a minor, controllable partner (per Britannica).

Hitler, who had lost the 1932 presidential election to Hindenburg, refused to accept less than the chancellorship. And even after the Nazis' losses later in 1932, it was impossible to form a stable government without them. Hindenburg appointed Hitler chancellor in January 1933. Shortly thereafter, the Reichstag fire allowed Hitler to sway Hindenburg into suspending civil liberties, paving the way for a total dismantling of German democracy (per The National WWII Museum).