Plans Napoleon Made That Never Happened

Napoleon accomplished a lot in his lifetime, conquering most of Europe and bringing the continent under a brief period of French domination. The French emperor had plenty of other lofty dreams, though many remained just that. He wanted to conquer Russia and split it up, but he did not seem to have had any concrete plans on how to do that. He wanted to emulate Alexander the Great and conquer India the hard way — by marching across Asia, despite the immense difficulties. In one fascinating case, he envisioned the state of Israel 150 years before it came into being.

Even after his final defeat in 1815, he never stopped dreaming. Napoleon remained a striver to the bitter end. But after such a rise to power, his fall from grace was rather anticlimactic — dying in exile on the remote Atlantic island of St. Helena in 1821.

He (allegedly) envisioned a Jewish state in the Holy Land

Napoleon's invasion of Egypt in 1798 was supposed to extend French control over trade routes to India. After the British destroyed his navy at the Battle of the Nile and left his army stranded in Egypt, however, Napoleon marched north into the Levant and Syria to attack the Ottoman Turks -– Egypt's nominal rulers. Once there, perhaps seeing an opportunity to create a political entity sympathetic to France, he allegedly adopted the cause of Zionism.

In 1940, a letter of disputed authenticity (via Jewish Virtual Library) from Napoleon to Jews everywhere was published, advocating for the creation of a Jewish state in the Holy Land. Peppered with references to the Old Testament prophets, the letter praised Jewish steadfastness and faith, despite persecution. He called for Jews to claim their "political existence as a nation among the nations, and the unlimited natural right to worship Jehovah in accordance with [their] faith, publicly and most probably forever" — before the opportunity fizzled out.

In 1800, Napoleon remarked that if he had been in charge of a Jewish state, he would have rebuilt the temple of Solomon, so Zionist sympathies to further his interest in the Middle East are plausible. Regardless, it was never disseminated. He allegedly planned to issue the letter from Jerusalem on Passover April 20, 1799. Instead, a plague forced him back to Egypt, and it appears he shelved the idea once it was no longer politically expedient.

Destruction of the British monarchy

Napoleon hated Britain and wanted to conquer it. He wanted nothing less than the total destruction of the monarchy and the British aristocracy that had given him and France so much trouble. Napoleon's physician on St. Helena, Irishman Edward O'Meara, told St. Helena Gov. Hudson Lowe in an 1817 letter how Napoleon had envisioned achieving this.

Napoleon's strategy, per O'Meara's account (via Fondation Napoleon), was to win over British commoners with the French revolutionary ideals of liberty, equality, and fraternity. Napoleon would have abolished the monarchy, the nobility, and House of Lords, and confiscated their property to solidify popular support. Britain would have become a republic for the first time since 1649. Obviously these were just promises –- Napoleon said that the whole point was to play the British public for fools by making them think he cared, so he could settle his score with the king.

O'Meara questioned whether the British public would have fallen for Napoleon's scam, noting they probably hated him and France as much as he hated Britain. A French invasion would have united British society against a common enemy. Some, O'Meara said, might even have torched London rather than see it fall to France. The emperor replied that he might have pulled off the conquest had he been able to seize London. He never got a chance to try, however, as trouble broke out between Austria and Bavaria that required his intervention.

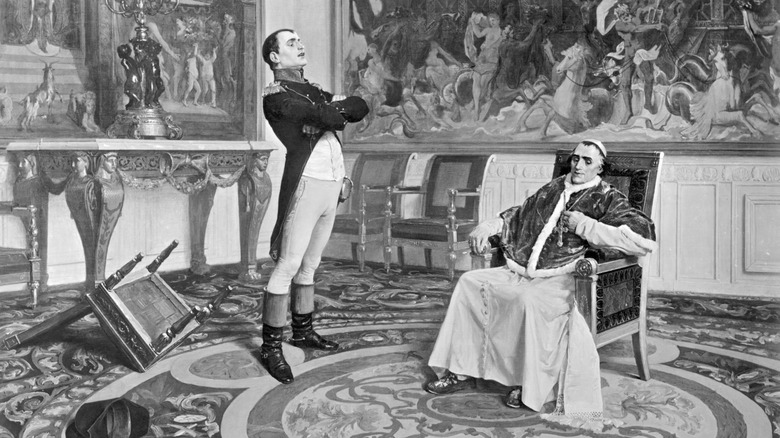

Subjugation of the Catholic Church

Napoleon, who had halted the French Revolution's persecution of Catholicism with the Concordat of 1801, considered Pope Pius VII (pictured above with Napoleon) his subject. He demanded the Papal States break off relations with France's enemies and allow Napoleon to run the French church. Pius refused, so Napoleon embarked on an attempt to subjugate the Catholic Church.

Napoleon started off by seizing church lands. Pius retaliated by rejecting Napoleon's nominees to French bishoprics. Napoleon upped the ante by threatening to reorganize the Catholic Church himself without the pope's input, annexing Rome and the Papal States, and threatening the pope with arrest. Although Napoleon had intended the arrest to be an empty threat, Gen. Etienne Radet went through with it in 1809. The guilt-ridden general was said to have remarked, "At that moment, my first communion flashed before my eyes!" (via Fondation Napoleon). Pius then excommunicated the emperor.

Napoleon subjected Pius to some five years of imprisonment, stressing the pontiff so much that he was given last rites just in case. But he survived, returning to Rome a hero after Napoleon's first defeat in 1814. Despite the ill-treatment, however, Pius did not hold bitterness against Napoleon, viewing him instead as a prodigal son. His efforts to return Napoleon to Catholicism paid off after Napoleon was imprisoned at St. Helena. Upon the emperor's request, the pope sent a chaplain who helped Napoleon return to the church with a deathbed confession, communion, and last rites.

His plans for a Russian bride were rejected

Before attempting his failed 1812 invasion of Russia, Napoleon tried to conquer the country through marriage after divorcing his first wife, Josephine, for failing to conceive an heir. Napoleon's first choice was Ekaterina Pavlovna, Russian Czar Alexander I's sister. Napoleon tempted the czar by offering to consider partitioning Russia's hated foe –- the Ottoman Empire. Alexander, however, delayed, saying he needed his mother's consent, while Ekaterina refused, preferring to marry a Russian commoner. In the end, she married the rather unappealing prince of Oldenburg.

Unfazed, Napoleon pursued Anna Pavlovna, Alexander's younger, 15-year-old sister. Ekaterina, her mother Maria, and the czar were caught between a rock and a hard place. If Anna married Napoleon and failed to conceive, she risked being set aside for a mistress or divorced at a very young age. Refusal, however, risked war with France. "If we refuse, Alexander, as monarch, will suffer a lot. If we agree, we would ruin my daughter. Only God knows would it be possible to avoid the distress for the State," Maria wrote to Ekaterina (via Gatchina Through the Centuries).

In the end, Napoleon grew sick of waiting and broke off the courtship, citing the inconvenience of bringing a Russian Orthodox priest to Paris, and married Marie-Louise, daughter of Francis I of Austria.

He never got to emulate Alexander the Great

Among Napoleon's more ambitious plans was the conquest of British India, which provided his hated rival with much of its wealth. After trying to curry favor with anti-British Indian rulers, he settled on emulating Alexander the Great by attacking India through Iran.

The idea was not originally Napoleon's –- it originated with Fath Ali Shah of Iran's Qajar dynasty. The shah needed an ally to protect his lands from Anglo-Russian encroachment. He saw Napoleon as that ally and sent dignitaries to negotiate an alliance. Under their agreement, Napoleon would assist the Iranians against Russia, while Iran would break ties with the British and allow French soldiers onto Iranian territory.

The plan failed because Napoleon could not keep his commitments. After war broke out between Russia and Iran in 1804, Napoleon, likely distracted with his wars in Europe against Russia, Austria, and Prussia, did not send Iran the promised aid. After rumors of 12,000 French soldiers marching into Iran dissipated, the shah was left disillusioned with Napoleon and quickly patched up relations with Britain before Russia could grab more of his territory. In the Anglo-Persian Treaties of 1809 and 1814, Iran agreed to sever relations with countries hostile to Britain. At the time, that meant France, meaning Napoleon's dream of emulating Alexander the Great was dead for good.

The Suez Canal failed due to a surveyor error

Napoleon wanted France to dominate trade with India and the Far East, which required control of Egypt and the Isthmus of Suez, where eastern luxuries had traveled from the Red Sea to the Mediterranean since antiquity. If the two bodies of water could be linked by canal, cutting out the overland journey through the desert, trade would be safer, faster, and cheaper.

According to S.C. Burchell's "Building the Suez Canal," Napoleon visited the Isthmus of Suez with engineer Jean-Baptise Lepere and ordered him to survey the land and determine the project's feasibility. Lepere calculated it was not possible, because the Red Sea's water level was 30 feet higher than the Mediterranean's, which would result in the Red Sea flooding into the Mediterranean and sweeping Egypt's coastline away.

French scientists protested, saying Lepere was wrong; it was unlikely two bodies of water so close to each other would have such an altitude differential. Lepere refused to publicly concede the error but was privately troubled. The ancient Egyptians somehow managed to link the two bodies of water with a canal that connected the Red Sea to the Nile around 2000 B.C. without any problems. Due to his error, Napoleon shelved the project, which was resumed after he died after Lepere's mistake was corrected. The canal officially opened in 1869, with the blessing of Napoleon's nephew, Emperor Napoleon III.

Learning to speak English

While on St. Helena, Napoleon decided to learn English with Count Emmanuel de las Cases who gave him daily lessons. He progressed from word lists to full sentences and eventually longer works such as letters, making the usual learner mistakes along the way.

Napoleon's English exercises show that when it came to language learning, he was like most people. He often transposed French/Italian syntax directly into English. For instance, according to the Fondation Napoleon, he wrote, "j write you this letter for say to you" instead of "to say" -– a clear example of a French/Italian intrusion. In another instance, he wrote, "time has not wings." Although this can be a poetic way of saying "time does not have wings" in English, it is more likely Napoleon directly translated the French. English spelling also tripped him up, writing "heavi," for "heavy," "somme" for "some," and in two cases of apparent German influence, "trink" for "drink" and "schal" for "shall."

De las Cases got Napoleon reading-proficient and taught him how to spell decently –- an admirable achievement for a man in his 40s locked up on a remote island. But he never gained full fluency. Napoleon's English friend, Betsy Balcombe, said he never abandoned his odd (likely Italo-French) inflections, while even de las Casas admitted native speakers could not understand him. Still not bad considering Napoleon made all that progress in just one year.

Going back home one last time, even in death

As Napoleon was dying on St. Helena in 1821 he requested in his last will to be buried in Paris, near the Seine River. But he also said, "If they forbid my corpse, as they have forbidden my body, a small piece of land in which to be laid, I desire to be buried with my ancestors in [the] Ajaccio cathedral in Corsica," as per Fondation Napoleon. That is engraved on a plaque on the wall of the cathedral today.

Napoleon's request must be contextualized in his final years, which were a journey back to his childhood. On St. Helena, the emperor had returned to Catholicism, which no doubt revived memories of his youth in Corsica and of the cathedral. After all, he had been baptized there and attended as a child. His uncle Luciano had been a deacon, and most of his family was buried there. So it makes sense that Napoleon wanted to go home where it all started -– even in death.

Unfortunately for Napoleon, this homecoming dream never materialized. The restored French monarchy did not want his tomb to become a magnet for its enemies, so the British gave him a military funeral on St. Helena. His remains eventually returned to France in 1840 for burial at l'Hotel des Invalides, meaning he never returned to Corsica even in death.

Uniting Europe

Napoleon claimed he wanted to unite Europe, writing, "I wished to found a European System, a European Code of Laws, a European judiciary; there would be but one people in Europe," according to historian Tigran Yepremyan, writing in Napoleonica: La Revue. The ideal advocated replacing Europe's monarchies with ethno-national states, based around some French Revolutionary ideals. He merged Italy and Germany's small states into larger kingdoms and republics. Countries like Spain saw the rise of constitutionalism, the abolition of feudalism, and other liberalizing reforms.

For all his high-sounding rhetoric, however, Napoleon only seemed interested in European unity if he and his family were in charge. He replaced the old aristocracy with a new one coincidentally made up of his relatives and supporters, like King Joseph Bonaparte of Spain, King Jérôme Bonaparte of Westphalia, King Joachim Murat of Naples, and ... Emperor Napoleon of France. He sidelined revolutionary ideals when convenient, turning republics he founded into kingdoms for himself and his allies. He was sometimes a republican, other times a monarchist, and at all times, an opportunist.

Napoleon's plan for European unity failed because he lost. After his defeat at Waterloo, his enemies met at the 1815 Vienna Congress to discuss how to prevent the ideas of the French Revolution that Napoleon had unleashed from making a comeback. But there was no putting the genie back in the bottle. As Yepremyan notes, Napoleon's legacy in the unification of European nation-states was there to stay.

Irish independence

"I would have separated Ireland from England, the former of which I would have made an independent republic," Napoleon bitterly remarked while in exile on St. Helena, according to Arthur Griffith's "Napoleon and Ireland." The Emerald Isle had always been of interest to the opponents of Great Britain, due to Irish resistance to British rule. Thus, promoting unrest in Ireland, and even Irish independence, was seen as an easy way to weaken Britain, something Napoleon attempted to exploit at least twice.

Following the 1798 Treaty of Campo Formio, which ended hostilities with Austria, Napoleon and France only faced Britain. Irish nationalists such as Wolfe Tone urged the French government to send Napoleon, then general in chief, to invade Britain and Ireland, promising the French would have local aid from Irish insurgents. Griffith claims, however, that Britain had bribed a handful of government officials, while others worried Napoleon would overthrow them. So, they sent him to invade Egypt instead. Three days after Napoleon left, the Irish rebelled, having fully expected aid from French forces. It failed.

After 1799, the invasion of Ireland never got beyond the fuzzy planning stage. Napoleon organized an Irish Legion in 1803, which was meant to grow into a full-fledged Irish army when an invasion of Britain eventually did happen. Napoleon promised Irish nationalists that he would make their independence a condition of peace. But Napoleon was never able to defeat the British, who ended up defeating him at Waterloo in 1815 and postponing hopes of Irish independence for another century.

Living the American Dream

After his defeat at Waterloo in 1815, Napoleon realized the game was up and began making plans for his post-imperial life. He decided, according to Ines Murat's "Napoleon and the American Dream," to become a natural scientist in the United States. "I want to embark on a new career," he wrote, "to leave worthy undertakings and discoveries behind me." He even had two ships ready to make the voyage but had to make it past the British navy.

In the end, Napoleon made the last-minute decision to surrender to the British, hoping they would grant him safe passage to the U.S. While in captivity, he busied himself with a biography of his hero, George Washington. The British, however, shattered his American dream by exiling him to the remote Atlantic island of St. Helena. After the British evaded American privateer True Blooded Yankee, which sought to rescue Napoleon and bring him to America, the former emperor's fate was sealed.

Reforging New France

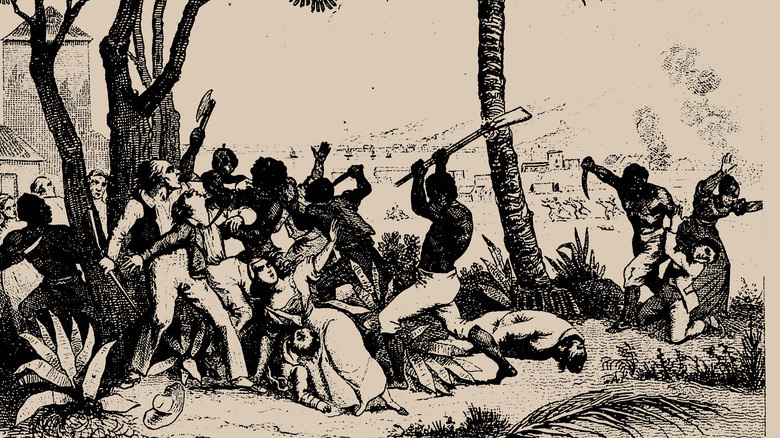

Napoleon had wanted to bring France back into play in the Americas, where its position had been greatly weakened with the loss of Saint-Domingue (modern Haiti), following the 1791 Haitian Revolution, a slave uprising that turned into an independence war. Pursuant to his goal, he engineered the reacquisition of Louisiana, which had been ceded to Spain decades earlier, and sent an expedition to recapture Haiti.

Napoleon's plans ran into two hurdles. First was the U.S., which wanted access to the port city of New Orleans for commercial purposes. French refusal to open the port to American vessels had spurred calls for war in Washington –- something Napoleon could not afford to deal with. Furthermore, because the territory spanned from the modern state of Louisiana to the Rockies and was sparsely inhabited, it was likely to fall to American settlers or the British anyway. France was better off selling it and using the money elsewhere. In 1803, France and Thomas Jefferson's administration agreed to the Louisiana Purchase, wherein the U.S. bought the territory for $15 million.

Napoleon's plans to retake Haiti, meanwhile, faltered when the Haitians defeated the French expedition sent to put down the revolution in 1802 and proclaimed an independent republic. However, in one of history's greatest twists, the Haitians offered some of the Polish soldiers in Napoleon's expedition citizenship and the opportunity to stay in Haiti. A handful took up the offer, and their descendants survive as a distinct cultural group within Haitian society to this day.

The conquest of Spain

In 1810, Napoleon seemed to have conquered Spain, as his brother Joseph triumphantly strode into Seville as the country's next king. The Spanish ex-king was in jail, Spain's war industries were in French hands, and the bloody revolt of 1807 was mostly suppressed. All that was left was to seize the final rebel stronghold of Cadiz. Napoleon's commanders figured Cadiz could wait –- the likelihood of the remaining insurgents resisting was slim.

Napoleon's delay proved to be a fatal mistake, although it was impossible to realize at the time. Spanish troops under the Central Junta did defend the city, turtling their remaining forces alongside British reinforcements in the heavily fortified town. Together, they held out for almost two years against continuous French bombardment.

Although Napoleon had defeated British Gen. Sir Arthur Wellesley's forces in Spain, the general had regrouped in Portugal, where he made a counterattack against Madrid. Napoleon, meanwhile, was planning his invasion of Russia. Thus, as British forces advanced on Madrid, Napoleon needed soldiers for the invasion of Russia, taking them from the siege of Cadiz and weakening the effort. Once Wellesley captured Madrid, the French forces withdrew to defend their rear. Not only had Wellesley kicked Napoleon out of Spain and torpedoed his plan to conquer the country at the 11th hour, he chased French forces into France itself and defeated them at Bayonne.