Strange Facts About Psilocybin Mushrooms You Never Knew

Some mushrooms are recognized for their tasty properties and others for their interesting aesthetics, but there is a class of fungus that has an altogether different and sometimes infamous reputation. These would be psychedelic mushrooms, which can induce mind-bending and maybe even life-changing symptoms when ingested. Some of the most common varieties contain a chemical compound known as psilocybin and were consumed by people for thousands of years before they were studied in labs.

Starting around the mid-20th century, psilocybin mushrooms quickly entered the cultural consciousness of many Western folks, became a promising research topic, and then got so associated with the countercultural movement of the 1960s that conservative parents and the U.S. federal government both classified psilocybin as a dangerous drug. While you may choose to ignore the warnings of Mom, Dad, and Richard Nixon, the government's classification of the compounds in psilocybin mushrooms as heavily regulated Schedule 1 drugs put a serious damper on further research.

But while psilocybin mushrooms may carry the tie-dyed reputation of blissed-out hippies, there's more to this fungus than cultural stereotypes or the federal government would have you believe. Besides a complex family tree and a history of human use that stretches over millennia, psilocybin mushrooms may now hold the key to helping some people in dire need of mental health support and allowing scientists to understand the complexities of the human brain further. With U.S. states increasingly decriminalizing psilocybin possession and consumption, it's time to learn more about this unique mushroom.

Many mushroom species contain psychedelic substances

Though you may be forgiven for thinking there's only one sort of psychedelic mushroom, the reality is that there are hundreds. More specifically, there are around 300 different species of mushrooms worldwide that contain psychedelic substances, typically psilocybin. Given how many there are, it's no surprise that this class of mushrooms presents a diverse range of shapes, colors, and other bits of fungal morphology, though many do turn a bluish color when cut or bruised due to the oxidation of psilocybin. However, it's worth noting that anyone who's foraging for any sort of mushrooms can come across poisonous or even deadly varieties, so it's always smart to consult with a mycologist or other expert before consuming.

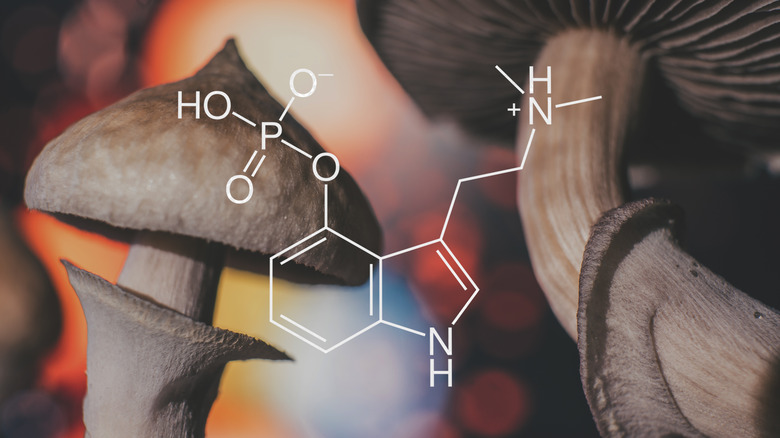

While it's fairly well-known, psilocybin isn't the only psychedelic compound that might be in a mushroom. Other species might contain psilocin, another relatively common psychedelic tryptamine, or less common ones such as baeocystin, norbaeocystin, and aeruginascin. Technically, baeocystin and norbaeocystin aren't psychedelic on their own but can be chemically transformed into psychoactive compounds. And as much as psilocybin and psilocin have been regularly neglected in scientific studies, the effects of the other three compounds have been even less studied.

As if that weren't already a pretty complicated soup of chemicals inside a little fungus, a 2020 study published in Chemistry found that psychedelic mushrooms can contain a suite of monoamine oxidase inhibitors that could make the effect of psilocybin and its like all the more powerful.

Psychedelic mushrooms alter connectivity in the brain

Once a person has consumed a mushroom with psilocybin, how does that compound start to work on their brain? First, psilocybin gets into one's neural pathways via the brain's serotonin receptors. Serotonin is a hormone that can induce warm, happy feelings and also has a role in regulating basic biological programs like sleep patterns. Once in the brain, psilocybin can increase connectivity between different parts of the brain, as a 2014 paper published in Interface, a journal of The Royal Society, found. Compared to a group of subjects given a placebo, those who ingested psilocybin also experienced the effects of this increased neural connectivity for longer periods. However, the exact mechanism by which psilocybin does this remains unclear.

Researchers have suggested that, though psilocybin may appear to scramble up brain activity, it's actually still fairly organized in there, if unusual compared to everyday brain organization. Similarly, regular low doses of psilocybin administered to rats appeared to increase connectivity in the animal subjects, as per a 2023 paper in Molecular Psychiatry.

But it doesn't stop there. Other research indicates that psilocybin from mushrooms can actually restrict activity in some parts of the brain. A 2022 study in Neuroimage found that psilocybin appeared to modestly increase connectivity in the brain's thalamus, but that it also decreased the function of parts of the brain related to spatial organization.

Ancient people used psilocybin mushrooms

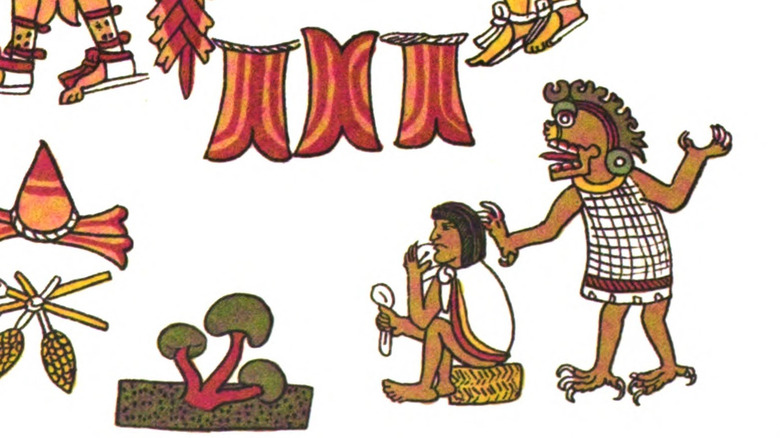

Psilocybin mushrooms have been consumed by humans for millennia, with some researchers even claiming that our ape ancestors likely chowed down on psychedelic fungi. One of the earliest depictions of what may be hallucinogenic mushrooms comes from southeastern Algeria, where the Tassili n'Ajjer site contains approximately 15,000 examples of rock art. Archaeological evidence indicates that humans used the site as early as 10,000 B.C. Amongst the many carvings and paintings at Tassili n'Ajjer is the striking figure of what's now popularly called the "mushroom shaman," seemingly outlined in the fungus. Researchers have since suggested that this figure has a religious purpose — and what other mushroom could be so important but one with psychedelic properties?

The Neolithic people of North Africa wouldn't have been alone in their use of psychedelic fungi. The mystical Eleusinian rites of ancient Greece included a wheat drink that may have been inoculated with hallucinogenic ergot (which, besides causing visions, can also induce intense vomiting, convulsions, and even gangrene once the fungus causes blood vessels to constrict in extremities).

In Mesoamerica, Spanish priests who accompanied 16th-century colonizers wrote of native people who consumed mushrooms and experienced intense visions. Mesoamerican art also appears to depict mushrooms in a religious context, with mushroom-consuming humans visited by gods and artworks of deities that appear to include the distinctive shape of psilocybin mushrooms native to the region. It may have also had a role in ritualized war and human sacrifice in some Mesoamerican cultures.

They weren't widely known in the West until the 20th century

Though there is abundant evidence that ancient people across the globe consumed hallucinogenic mushrooms for many generations, they were decidedly low-profile in Western society for a long time. Many even thought they were entirely fictional until samples were collected and identified in the 1930s.

Then, in the 1950s, things changed even further. Married couple and very enthusiastic amateur mycologists Gordon and Valentina Wasson traveled to Mexico in 1955 and, with the indigenous people of a remote village, consumed psilocybin mushrooms. Gordon, a banker, published his account in a May 1957 issue of Life magazine. Valentina, a doctor, wrote of her experiences on the trip that same month in This Week. Both spoke of dramatic visions that included bright, swirling colors, an altered perception of time, and, for Valentina, "several handsome gold dragons" that she observed crawling in the bottom of a vase.

The Wassons weren't discovering anything new, as the indigenous folks who supplied the mushrooms could have told you. Indeed, it later became clear that the CIA was keen on the topic and had partially funded their travel, though apparently without the Wassons' knowledge. They did, however, bring wider recognition to the subject of psilocybin mushrooms at a time when many Westerners (including physicians and research scientists) were beginning to experiment with psychedelics.

Psilocybin mushrooms were researched in the 1950s

By the mid-20th century, a few scientists were just beginning to investigate the potential of psychedelic drugs. In the United States, some mental health professionals were even giving patients doses of hallucinogens such as mescaline and LSD, the last of which had been synthesized in a lab in 1938. They observed that these psychedelics dramatically altered a person's experience of the world, sometimes bringing a new sense of connectedness, allowing others to battle addiction, and also mimicking the symptoms of mental disorders like schizophrenia.

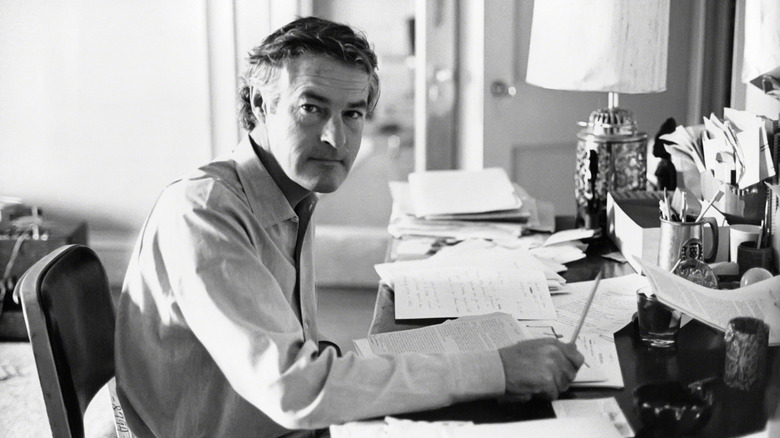

In 1958, Swiss chemist Albert Hofmann, who had helped synthesize LSD and examined its effects in the 1940s, received a sample of psilocybin mushrooms from mycologist Roger Heim. Heim had accompanied Valentina and Gordon Wasson on a 1957 trip to Mexico to further study psychedelic mushrooms, where he had gathered a fungi sample that he was able to continue growing back in France. He sent a sample along to Hofmann's lab.

Hofmann — who decided to ingest some of Heim's dried mushroom powder to see if it was really psychoactive — was eventually able to isolate the chemical components of the mushroom. After some more sampling, volunteers in Hofmann's lab were able to identify one chemical as the main hallucinogenic culprit. Hofmann deemed it psilocybin. Another smaller psychoactive compound isolated from the sample was named psilocin.

There was once a Harvard Psilocybin Project

It's all but impossible to talk about psychedelics without mentioning Timothy Leary. To some, he was a wild-eyed psychologist who pushed the boundaries of his field too far, especially when it came to his championing of psychedelics and lax take on informed consent. To others, he was a trailblazer. To Harvard, he was a faculty member. Leary joined the university as a lecturer in 1959, soon establishing the Harvard Psilocybin Project with fellow psychologist Richard Alpert. Both administered psilocybin to volunteers, who were mostly told what was going on and then recorded subjects' reactions.

Leary and Alpert were fired from Harvard in 1963, in part because the Harvard Psilocybin Project allegedly gave undergraduates psychedelics. Other faculty members also questioned both the legitimacy of the research and the safety procedures (or lack thereof) put in place by Leary and Alpert. Leary eventually became a countercultural figure who focused on popularizing LSD (to the chagrin of many, including President Richard Nixon and academic researchers who wanted to seriously study psychedelics). After a prison sentence and jailbreak, Leary was also briefly an international fugitive before settling down in California and dying of prostate cancer in 1996.

If he were still alive, Leary would surely take great interest in Harvard's recently renewed stake in psychedelic research. In October 2023, the university enthusiastically announced that it would create a world-class program for the Study of Psychedelics in Society and Culture.

Psilocybin ran into serious legal issues

Though some scientists were keying into the therapeutic potential of psilocybin mushrooms by the 1950s, one major roadblock would soon appear: the federal government. If confronted, officials in the government would probably have shifted the blame onto a hippie counterculture movement that they believed threatened regular Americans. Whatever the reality, psilocybin mushrooms became an object of federal suspicion.

So, under the 1970 Controlled Substances Act, psilocybin and psilocin were designated as Schedule 1 drugs by the U.S. Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA), a status they still hold today. This means that the DEA maintains that psilocybin has no "currently accepted medical use and a high potential for abuse," though there is no evidence that people can become physically dependent on the substance.

This change in status for psilocybin and other psychedelics effectively slammed the door shut on medical and academic research for decades, as researchers would have to jump through a series of highly regulated hoops to examine psilocybin and test it on human subjects. Ironically enough, psilocybin is now being investigated as a way to help patients overcome substance use disorder.

How people experience psilocybin mushrooms depends on many factors

So many factors can influence someone's experience with psilocybin mushrooms that you may feel like you need a mycology degree to understand it all. Even scientists will admit that there are many factors that can lead to dramatically different trips, few of which we fully understand. What species was consumed, for instance? That alone is no small task, given the hundreds of psychoactive mushroom species out there, all of which can have different levels and combinations of compounds. What kind of environment did those individual mushrooms grow in? How were they prepared and consumed? Is anyone keeping careful notes of their experience?

That's not even getting into less easily defined psychological factors. What state of mind is a person in? If they're not in the most stable of psychological realms to start, then chowing down on psilocybin mushrooms or any other psychedelic could exacerbate existing mental health issues. Even without preexisting conditions, psilocybin mushrooms can induce unpleasant symptoms like nausea and emotional upset. While scientists are pretty united in saying that psilocybin can make noticeable changes in a person's brain, it's still unclear how that happens or what can produce the sometimes very dramatic differences in experience amongst individual mushroom consumers.

Animals have been observed consuming psychedelic mushrooms

Close observations of both domestic and wild animals have pretty strongly indicated that quite a few other species know about psychoactive mushrooms. Reindeer in Siberia reportedly consumed Amanita muscaria caps often enough that they inspired people to try the mushroom (also known as fly agaric) for themselves. They've even been observed doing so by modern camera crews. Technically, A. muscaria doesn't contain psilocybin as its active ingredient. Instead, the psychoactive compounds appear to be muscimol and ibotenic acid (muscarine was thought to be part of the group, too, but A. muscaria doesn't appear to contain much of it). People who consume fly agaric can experience serious side effects that might be as bad as seizures, coma, and death, so it's best just to appreciate its distinct look and leave the eating to the reindeer.

It's not just reindeer who are interested in psychedelic mushrooms, either. Writing in "Animals and Psychedelics," ethnobotanist Giorgio Samorini relates the tale of his encounter with a male goat in the Italian Alps. The animal was aggressively interested in the psilocybin mushrooms Samorini had just collected. After knocking Samorini down, the goat ate the mushrooms. Then, the whole herd descended and mowed through the mushroom patch Samorini had just visited. He has since learned that goat herds appear to claim some patches, intentionally consume psilocybin mushrooms, and appear to be under a psychedelic effect afterward.

Psilocybin mushrooms may alter personality long-term

Many people who consume psychedelics likely expect their experience to have a short duration, lasting a few hours or, at most, a day, depending on the particular compound and how much was ingested. But modern research indicates that the psychological effects of psilocybin mushrooms may be much, much longer-lasting than the average 24 hours that the mushroom's compounds linger in one's body.

How long? One study published in a 2018 issue of Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica found that test subjects with treatment-resistant depression who were given either a 10 or 25-milligram dose of psilocybin showed markedly lowered neurotic tendencies and increased rates of extroversion — three months after their single dose. This study only included 20 participants, but other research indicates that a carefully managed psilocybin mushroom trip (that is, under the supervision of doctors and mental health professionals) can produce significant psychological changes that can last for weeks or months at a time.

A 2020 study published in Scientific Reports, this time with 12 subjects who had no known depression or other health issues, also showed significant personality changes one month after a relatively hefty 25-milligram dose of psilocybin. More specifically, troublesome issues were briefly reduced, while positive outlooks and increased neural connectivity appeared to last when subjects were reexamined a month after their single dose.

Psilocybin mushrooms show promise in treating depression

Though psilocybin mushrooms are still very much considered a Schedule 1 drug by the FDA, they are once again the subject of growing scientific interest despite the existing hurdles of federal regulation and research funding. And if you've heard of psilocybin in a research context, then chances are that you've heard of its promise as part of treatment for depression. Psilocybin has been especially interesting for those looking into treatment-resistant depression, currently defined as depression that persists even after a patient has tried at least two courses of more standard medications.

Research published in a 2023 issue of The New England Journal of Medicine described the use of psilocybin in a trial of 233 subjects with treatment-resistant depression. All received a single dose of psilocybin, with 79 receiving 25 milligrams, 75 consuming 10 milligrams, and 79 consuming just 1 milligram. Three weeks out, all had fewer depressive symptoms, with the 25-milligram group experiencing the largest change when compared to the 1-milligram control group.

The tricky part: even now, no one's sure just what psilocybin is doing in the brain. Yes, researchers are confident that it does something to or with a person's serotonin receptors, but beyond that, it's not obvious what this compound is doing or why it has helped numerous people with difficult-to-treat depression.

Psilocybin mushrooms may alleviate mortal fear

We all experience fear throughout our lives, but for some, that emotion can become debilitating. From generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) to post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), a variety of conditions can make navigating emotions and the everyday world seem impossible. This is where psilocybin mushrooms may be able to help. A study involving mice indicated that a psilocybin derivative, 4-OH-DiPT, may have anxiety-reducing effects on a faster but potentially less long-lasting timescale compared to mushroom-derived psilocybin (via Neuropsychopharmacology). Human trials, like those described in a 2022 issue of Current Topics in Behavioral Neurosciences, indicate much the same, though medical practitioners caution that stressful psychedelic experiences can exacerbate trauma, making it all the more important that patients receive psilocybin under the care of medical and mental health professionals.

For terminally ill people, psychedelics may help to increase their sense of connectedness and soothe fears related to what may or may not await a person after their physical death. A study published in 2022 in PLoS One surveyed 3,192 adults, of which 933 had near-death experiences, while the remainder had consumed psychedelics. Many of the latter group described psychedelic experiences that were remarkably similar to non-drug-induced near-death experiences. The psychedelics used by the subjects included psilocybin, as well as LSD, ayahuasca, and DMT. Both groups reported that they were less afraid of death after their experiences, an effect that lasted long beyond the initial event and which a majority of subjects found to be deeply meaningful.