Why There Are Few Copies Of The Wicked Bible Left Today

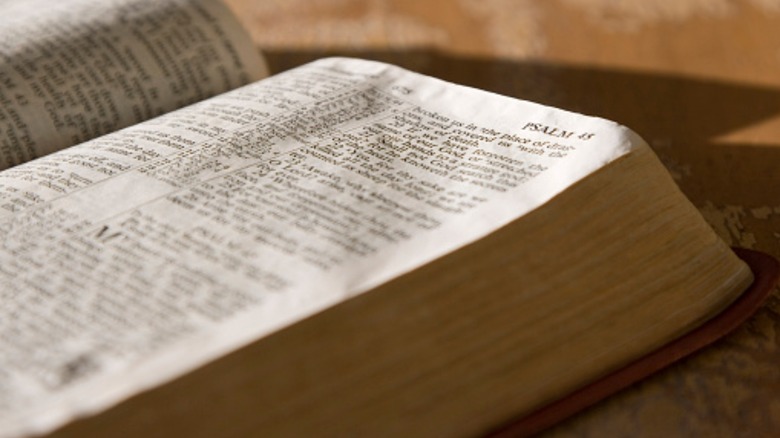

Whether you're a believer, agnostic, or atheist, it is fair to say there are a few life lessons that can be learned from a copy of the Bible, which is considered a holy text in several world religions. The commandment "Thou shalt not kill" feels like something everyone can use, even though it's arguably self-evident from a moral perspective.

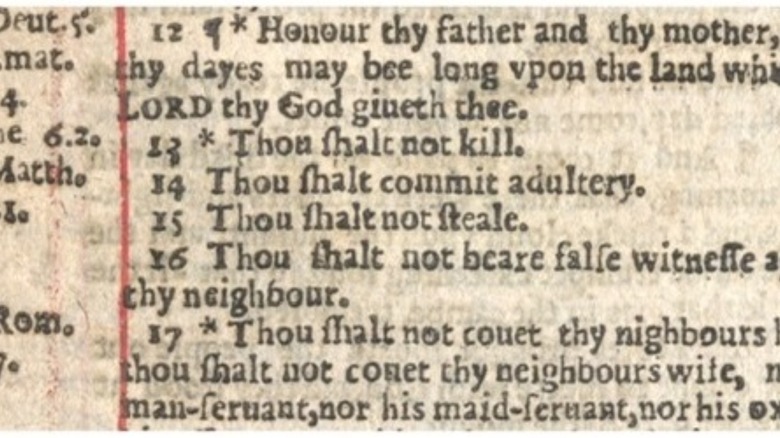

However, one infamous version of the text which has come to be known as the "Wicked" Bible goes against the grain when it comes to Biblical morality. In it, readers are given the command "Thou shalt commit adultery," subverting the creed of monogamy that exists in most world religions.

The immoral commandment occurred in thousands of copies of the King James Bible printed in the 17th century. Unsurprisingly, in the religious climate of the day, it caused a major stir, leading to the recalling and mass destruction of the offending copies. But not all copies of the "Wicked Bible," as it has since been dubbed, were given up, and today, the few that remain are priceless collectors' items.

A costly mistake

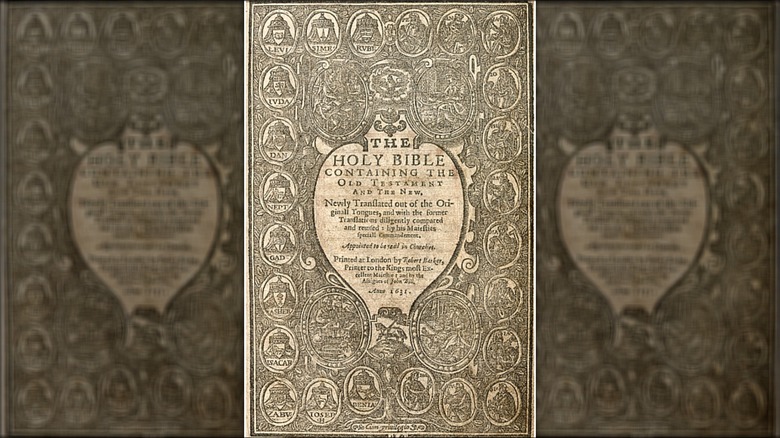

The origins of the Wicked Bible go all the way back to 1631, just two decades after the first publication of the King James Version of the Bible, which is considered a landmark English translation. It was the work of Robert Barker and Martin Lucas, two London printers who were entrusted with producing a new print run of the holy text. Though the Guttenberg Bible had been around for two centuries by that point, printing was still a laborious and expensive affair compared to printing today and required a great deal of skill on behalf of the printers.

The edition's commandment was in fact a misprint, which according to The Atlantic was only discovered a year after the print run began. By that point, around 1,000 of the offending Bibles had been printed, which were ordered to be gathered up under royal decree and, being considered blasphemous, summarily burnt. Barker and Lucas were taken to court, stripped of their printing licenses, and fined a sum of £300, a fortune at the time. Per The Guardian, some historians question whether the misprint was accidental or in fact a bit of intentional mischief.

Auctioning adultery

Despite the order to destroy all copies of the Wicked Bible, by the 2010s around 10 copies were known to remain in existence. By then, those copies that remained had come to be considered important historical objects, both of interest to academics and private collectors willing to pay big money for them in the rare book market.

In 2015, several news outlets reported that a copy had come up for auction at London's prestigious Bonhams auction house. It was given an estimate of £10,000 to £15,000 ($15,500 to $23,300), though it eventually sold for more than double that: a remarkable £31,250 ($48,700).

Since then, several other copies of the ultra-rare edition have emerged, including a copy uncovered in Christchurch, New Zealand, apparently brought there in the 1950s by a bookbinder named Don Hampshire. It only came to light with Hampshire's death, after which a Kiwi family bought it in a sale and brought it to the city's university for inspection. It is the first known copy to have been discovered in the southern hemisphere, one of around 20 that are now believed to exist.

A second blasphemy?

According to several sources, the invitation to commit adultery isn't the only thing wicked about the Wicked Bible. One widespread story claims that the 1631 not-so-holy text — which was reportedly riddled with other printing errors — contained another eyebrow-raising misprint that would have similarly outraged readers of the day.

The Salt Lake Tribune claims that the misprint was found in a line of Deuteronomy 5:24, which is supposed to read: "And ye said, Behold, the LORD our God hath shewed [shown] us his glory and his greatnesse." However, per the source, an error in the last word of the sentence means that the Wicked Bible tells readers that God showed his "great-asse" ... though "ass" would only have been interpreted by 17th-century readers to mean an animal.

While there has been some academic discussion of a second major misprint in the Wicked Bible, not everyone is convinced. Rob Ainsley of the British Library, for example, wrote a letter to the London Review of Books in 2009 claiming that the story is nothing more than a humorous fallacy.