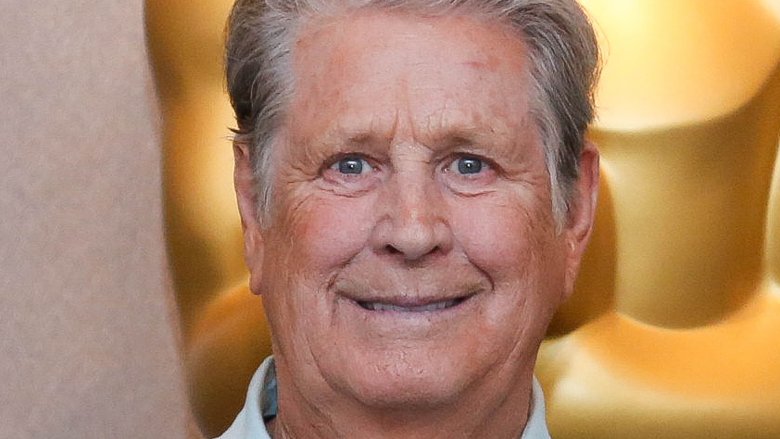

The Untold Truth Of Brian Wilson

When one thinks of the Beach Boys, there are usually a few specific things that come to mind. Things like catching a wave, needing some help from some woman named Rhonda, and having fun, fun, fun 'til her daddy takes the T-Bird away. Much of the band's formidable output over the decades has skewed toward the lighter side of the musical and lyrical spectrum, which is a touch ironic. The band's de facto leader (and, for most of their existence, chief composer, songwriter, and producer) Brian Wilson has never exactly been a happy-go-lucky guy.

A great deal of Wilson's life has been one big struggle — against his bandmates, addiction, mental illness, and his own limitations — and considering everything he's gone through, it's kind of a miracle that a) he's still kicking around, and b) he literally changed the way pop music is recorded and produced forever. He's repeatedly been labeled a genius, and even though he himself has consistently rejected that label, you know what they say about what one should do when the shoe fits. Let's take a deep dive into the life, career, and endless struggle of one of the flat-out greatest artists the world of pop music has ever seen: the untold truth of the legendary Brian Wilson.

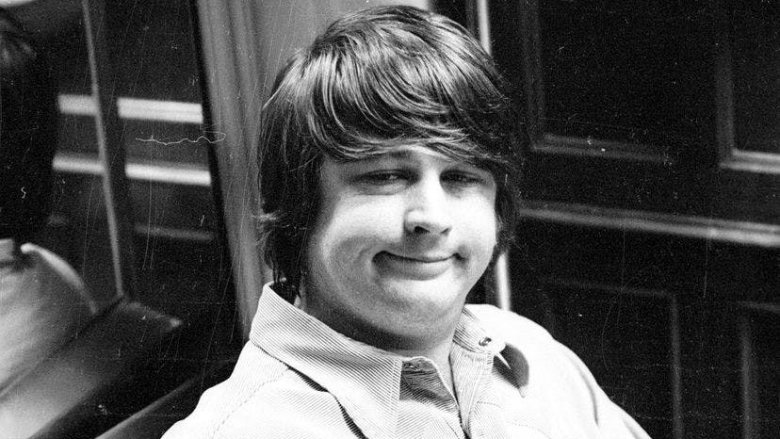

A prodigy from the start

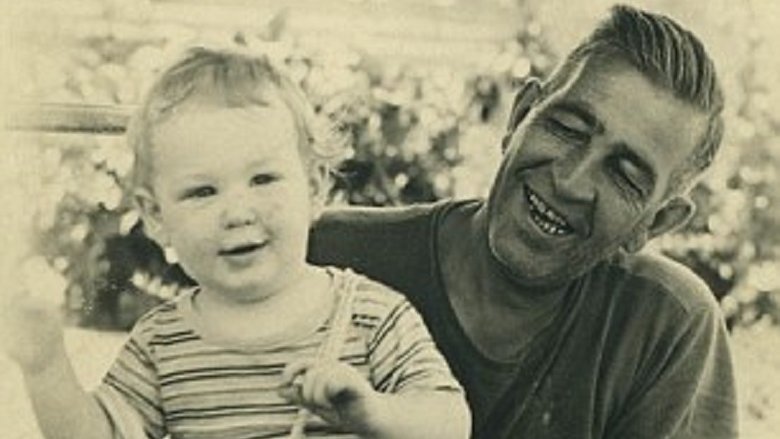

Wilson grew up in a musical family; his father, Murry, was a small-time songwriter and pianist, and his mother, Audree, also played the piano. Unfortunately, Murry was short-tempered and abusive, and Audree was an alcoholic. As a result, Wilson and his brothers, Dennis and Carl, had a mixed bag of a childhood, with their parents regularly alternating between engaging their budding musical talents (the brothers learned to sing and harmonize at home at an early age) and physically smacking them around; Wilson once said in an interview that he "had a good childhood, except for my Dad beating me up all the time."

The boy dealt with his situation by becoming prodigiously gifted on the piano, beginning to write his own compositions as a teenager. Over the years, he and his brothers' harmonies also became startlingly cohesive — all of which is much more impressive for the fact that Wilson was (and still is) almost completely deaf in one ear. In his 1991 autobiography Wouldn't It Be Nice, he summed up his trajectory succinctly: "An abused child, I turned myself into a boy wonder piano player and wrote the Beach Boys into rock and roll's Hall of Fame." Indeed he did — but before his famous band could get off the ground, there were a couple of early false starts.

Early group efforts and a well-timed fad

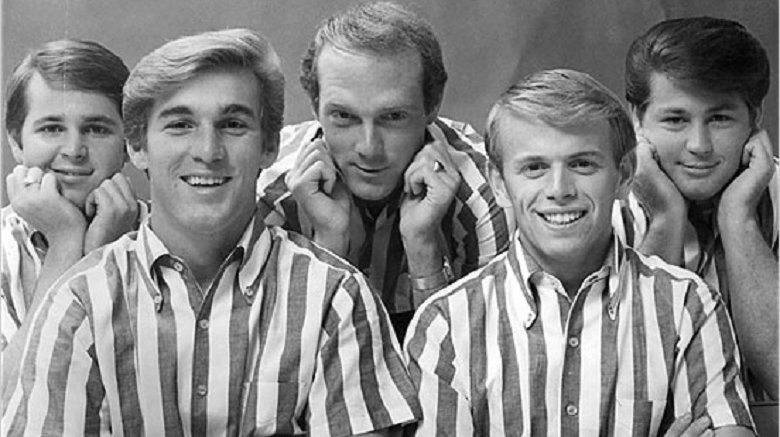

As teenagers, Brian and his brothers formed their first group with friends Mike Love and Al Jardine — but this being the early '60s, they cycled through a few band names that were wholly of their time before finding their identity. They began their career as Carl and the Passions (a moniker they would later revisit on the 1972 release So Tough) before taking on the name The Pendletones, in reference to a popular style of shirt (the "Pendleton") worn by those crazy kids at the time. This trend had largely been established by the beach-going teens of the Wilsons' native southern California, and when the Pendletones somehow failed to make much noise on the music scene, Dennis suggested that the band lean into a popular watersport fad that these Pendleton-wearing dudes were crazy into.

The result: the 1961 single "Surfin'," the first single released under the Beach Boys name. While the tune peaked at #75 on the national chart, it exploded in popularity regionally, and the brothers figured they might as well ride out the wave, so to speak. It turned out to be a far bigger wave than anybody could have reasonably expected.

Huge success, and an even bigger crash

The success of "Surfin'" prompted Capitol Records to come knocking, and with Murry acting as their manager, the Boys set about recording their first album, 1962's Surfin' Safari. With nine of its dozen songs written or co-written by Brian, the record broke into the top 40 on the U.S. charts — and even though the British Invasion was beginning to ramp up in earnest, the Boys kept the streak going. Over the next few years, classic albums such as Surfin' U.S.A., Surfer Girl, and All Summer Long kept the hits coming. Between 1962 and 1966, the band notched no fewer than 20 top 40 singles.

Unfortunately, things were going on behind the scenes which belied the band's simple, wholesome image. Brian fired his father as manager after a blow-up in the studio in 1964, and even as the mental health issues that would plague him for the rest of his life were beginning to make themselves known, Brian was beginning to lean toward a more complex, sophisticated style of songwriting and production that didn't always sit well with his bandmates. In the middle of a 1964 tour, Wilson suffered a panic attack while on a flight to Houston, an incident that led him to recuse himself from touring with the band. His resulting isolation had a couple notable effects: His mental state became increasingly fragile, and his musical ideas became increasingly advanced.

Fear of the stage

Wilson wasn't just panicking over nothing on that fateful flight; he had never felt entirely comfortable performing onstage, and at the height of the Beach Boys' popularity, he had developed a downright aversion to it. For a famous rock star, he had the distinct look of a man who would literally rather be anywhere else on Earth whenever he was performing, and his tremendous workload in writing and producing all those hit singles was contributing to a mental state that was growing more tenuous by the day.

After quitting touring, Wilson immersed himself fully in the studio, and it appeared to be a pretty good deal for everybody; the Beach Boys were free to tour without an extremely reluctant member, and Wilson — completely in his element — was free to let his creativity run wild, experimenting with new ideas and techniques without any input or interference from the rest of the band. He was, however, also doing a little experimenting of another sort, which turned out to be the mother of all double-edged swords.

A lifelong struggle

In case you're not a ridiculously talented musician suffering the effects of a childhood filled with abuse whose ideas are so far ahead of their time that even your closest musical partners struggle to understand them, just know that it can be tough. It also doesn't help, in such a situation, to become involved with psychedelic drugs. But that's exactly the path Brian Wilson took, and in his already delicate mental state, his experimentation took a rapid and permanent toll. In an interview, he said that shortly after his first bout with psychedelics at the age of 25, he began to hear voices in his head, and they weren't saying nice things.

"I knew right from the start something was wrong," Wilson said. "[The voices] say things like, 'You are going to die soon,' and I have to deal with those negative thoughts. ... It does dull you a little bit at first, but once you get used to it, it doesn't bother your creative process." Wilson never even thought about receiving treatment until he was in his 40s, and he says that to this day, those voices have never gone away — he's simply learned to deal with them. One of the ways he did this was to create mind-blowing music capable of making freakin' John Lennon phone to explain that Pet Sounds was the greatest album ever made, and that's not an exaggeration.

Brian's masterpiece

While his bandmates were out on the road, Wilson sought inspiration in the form of new music, and in 1965, the record that was turning his (and everyone else's) crank was the Beatles' Rubber Soul. "[It] blew my mind," he would recall years later. "I liked the way it all went together, the way it was all one thing. It was a challenge to me to do something similar. ... I didn't want to do the same kind of music, but on the same level." Wilson enlisted world-famous L.A. studio musicians the Wrecking Crew to help him lay down the compositions forming in his head, and the result was something darn near otherworldly.

That would be the Beach Boys' 1966 classic album Pet Sounds, on which Wilson definitively blew up pop music's conventions in regard to chord progressions, song structure, recording techniques, and pretty much everything else. The record redefined what was possible to achieve in a studio, especially in terms of stereo recordings. (And don't forget, its mastermind only had one good ear.) Pet Sounds directly inspired the Beatles to up their game with their '66 album Revolver, which prompted Wilson to respond with the single "Good Vibrations," almost certainly the most complex pop recording ever at the time. The Fab Four's next volley was a little album called Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band, considered by many to be the greatest album of all time ... except by those who would award the title to Pet Sounds.

Brian's other masterpiece

The bulk of the album that would've been the follow-up to Pet Sounds wouldn't see the light of day for almost four decades. Wilson recruited lyricist Van Dyke Parks to help him write Smile, an interwoven, unconventional ode to Americana unlike anything he, or anyone else, had ever done. With lyrics bordering on surrealism and arrangements more in line with classical music than pop, Smile may have changed the course of rock — had the Beach Boys not hated most of it. Mike Love in particular was incredibly hostile toward the material, and so — plagued by self-doubt and without the support of his bandmates — Brian abandoned the project.

While many of its songs made it onto future releases — such as the completely rejiggered Smiley Smile from 1967 and Surf's Up from 1971 — the album that might have been remained the stuff of legend until 2004, when Wilson, Parks, and Wilson's live musical director Darian Sahanaja reconstructed the original vision from a series of old tapes and their memories. The entire album was arranged for live performance, and after a series of successful presentations in London, the trio took to the studio to put it down properly. While the result demystified the legend a bit, there was no denying its immense ambition and artistry; had it been released in the '60s, there's no telling what a towering influence it may have had (or how it might have prompted the Beatles to respond).

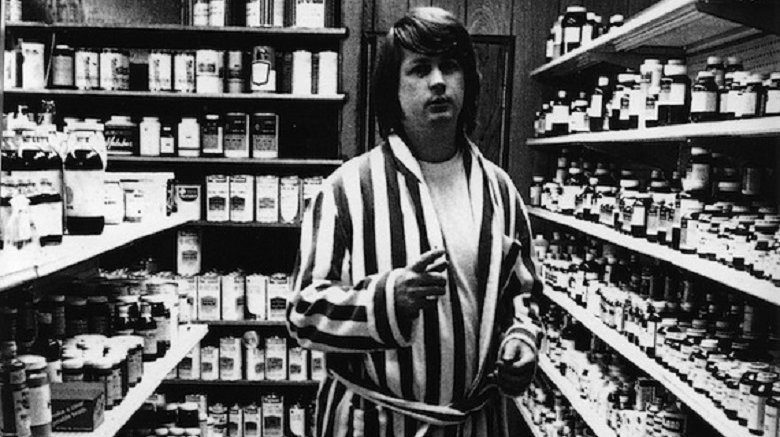

He literally dug his own grave

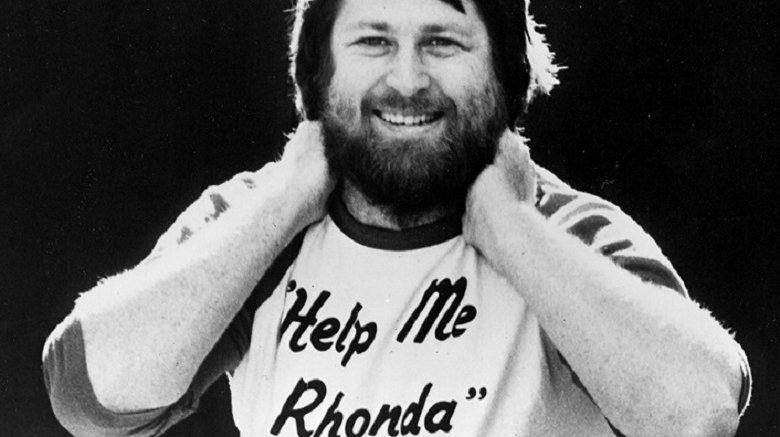

During the recording of the ironically titled 1968 album Friends, Brian Wilson's erratic behavior and perfectionism in the studio had him so at odds with the rest of the Beach Boys that they were all pretty much ready to strangle each other. Wilson finally decided to address his anxiety by checking himself in to an institution, but this didn't last long; upon his departure, he went home and stayed there for about three years.

He continued to write music regularly during this period, and while some compositions trickled down to the Beach Boys, many of them simply vanished into the ether. Touring Beach Boy Bruce Johnston recalled, "Brian went through a period where he would write songs and play them for a few people in his living room, and that's the last you'd hear of them. He would disappear back up to his bedroom, and the song with him." Wilson's non-musical activities during this time amounted to hanging out with the likes of Alice Cooper and Iggy Pop, and just doing all of the drugs. Friends grew concerned that he might be suicidal, owing to such incidents as the time he literally dug a grave in his backyard and asked his wife, Marilyn, to push him in. Instead, she decided to seek the help of a therapist — a very good decision that totally went haywire.

A shady therapist

Marilyn sought out self-styled therapist to the stars Eugene Landy (pictured, right, with Brian) in 1975, who used an odd combination of aggressive medication and forced physical fitness to attempt to rehabilitate Wilson. He was fired after a year due to his outrageous fees (north of $400,000 per year) but rehired by the Beach Boys' manager in 1982; in the intervening years, Brian had divorced, ballooned to over 300 pounds, and increased his drug intake in earnest.

Landy's solution to Wilson's every problem seemed to be more drugs, and the extent to which he was insinuating himself into the star's life started to look excessive, if not downright unethical. By the mid-'80s, he had proclaimed himself Wilson's manager and creative partner, accompanying his charge to interviews dressed like a more flamboyant Rod Stewart and accepting songwriting credits on several of Wilson's solo albums. Fortunately, while out shopping for a new ride, Wilson met car saleswoman Melinda Ledbetter, who was familiar with Wilson's past and knew an abusive situation when she saw it. "There was a total parallel between Murry and Landy," she would later say. "Because Brian came from such dysfunction, it was hard for him to recognize how dysfunctional the situation with Landy was." Ledbetter joined forces with Brian's family to free him from the grasp of Landy, who had gone so far as to make himself the sole beneficiary of Brian's estate. Their efforts were successful, and the quack was banned from contact with Wilson by the courts in 1992.

Sweet Insanity

Perhaps the single most bizarre thing to come from Wilson's association with Landy is the unreleased 1989 album Sweet Insanity. (Pro tip: If your therapist encourages you to record and participates in the creation of an album by that title, you may not have the most responsible therapist.) We may never know what wonders the complete album held because according to Wilson, the master tapes were stolen by some benevolent soul who rightly decided that it need not be inflicted upon the world. But of course, portions have made their way online in recent years — and this is how we know that, at the age of 47, Brian Wilson decided it was time to rap.

Shockingly, the track — titled "Smart Girls" — was produced by Delicious Vinyl co-founder and one-time Dust Brother Matt Dike, but it's safe to say it bears little resemblance to the Beastie Boys' Dust Brothers-produced masterpiece Paul's Boutique. Over the jankiest beat 1989 had to offer, Wilson spit hot rhymes ("My name is Brian and I'm the man / I write hit songs with a wave of my hand") as extremely ill-fitting snatches of Beach Boys tunes occasionally intruded upon the track to back up his boasts. The song might just as well have been used against Landy in court as proof that he was unnecessarily medicating Wilson because only massive amounts of drugs could have made anyone think "Smart Girls" was a good idea.

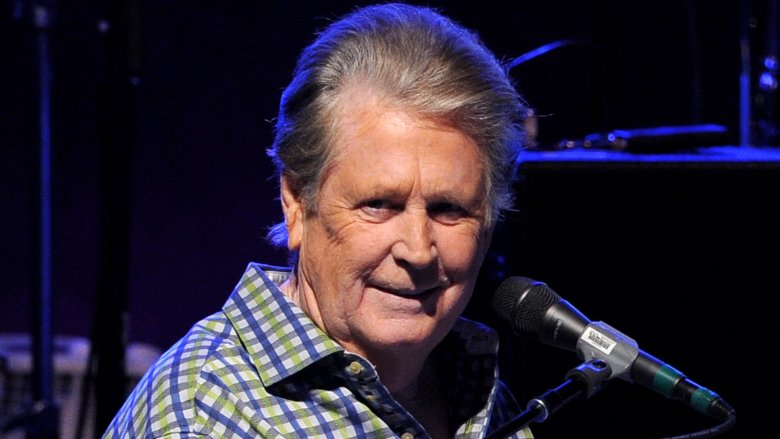

Back to life

Fortunately, along with Landy's departure from his life came something of a personal and professional resurgence for Wilson. He married Ledbetter in 1995 and released the well-received solo albums Orange Art Crate ('95) and Imagination ('98). He overcame his fear, self-doubt, stage fright, and those nagging voices to finish off Smile and perform it for adoring crowds. He was inducted into the Songwriters' Hall of Fame in 2000 (he and the Beach Boys had already made the Rock Hall in 1988), and in 2005 he picked up a Grammy for Best Rock Instrumental for "Mrs. O'Leary's Cow," a number from Smile he had started working on way back in the '60s.

Though the Beach Boys had officially called it quits after the death of Carl Wilson in 1998, Love and Johnston had carried on touring under the name, while Jardine joined Brian on the road for a 2006 tour in which he performed his masterpiece Pet Sounds in its entirety. Then, in 2012, came a small miracle — Wilson joined Love, Jardine, Johnston, and original guitarist David Marks (who had left the band in 1963) for a reunion tour and a new album, That's Why God Made the Radio.

Mind of a genius

Brian Wilson has always been a man fueled by his demons: his difficult childhood, his tendency to second-guess himself at every turn, his struggles with virtually every drug known to man, and those amazingly persistent voices. But one listen to Pet Sounds will tell you everything you need to know about his most valuable form of therapy in dealing with those demons: his music, without which he probably wouldn't have survived to adulthood, let alone old age. His ability to make the complex appear simple in constructing his "teenage symphonies to God" is unsurpassed in the world of pop, and the composition and recording techniques he pioneered have embedded themselves so deeply that his influence has certainly been felt by multitudes of artists who didn't even realize where their awesome ideas originated.

He's been called America's Mozart (although he himself was always partial to Bach), and even though he's now in his 70s, his process remains largely the same, and he won't be going anywhere anytime soon. When Rolling Stone asked him what he thought about retirement, he said, "Retirement? Oh, man. No retiring. If I retired I wouldn't know what to do with my time. What would I do? Sit there and go, 'Oh, I don't want to be [old]?' I'd rather get on the road and do concerts and take airplane flights." Spoken like a man who has kicked the crap out of a demon or two.