Did George Washington Approve Of The Boston Tea Party?

The Declaration of Independence was written and proclaimed in Philadelphia, but Massachusetts has long been deemed the birthplace of the American Revolution. Per The American Revolution Institute, it was the colony with the greatest autonomy, not only in America but in the whole of the British Empire, and its people were the least shy in resisting measures imposed by the mother country. Brief overviews of the lead-up to the Revolution in school curriculums and timelines like Britannica's lean heavily on developments in Massachusetts and particularly in Boston: protests against the Townshend Acts, the Boston Massacre, and the Boston Tea Party of 1773.

In simplified presentations, these acts can seem like defiance on behalf of all the colonies, answered with oppression by Britain. But Massachusetts was not the whole of America. There were sharp divisions between the colonies so profound that, once the business of revolution was over, some observers were convinced that their union would fall apart (per Balkanized America). And if the cream of American society, those men who would become the Founding Fathers, all had grievances with Great Britain, they did not uniformly approve of all that went on in Massachusetts before the Revolution began.

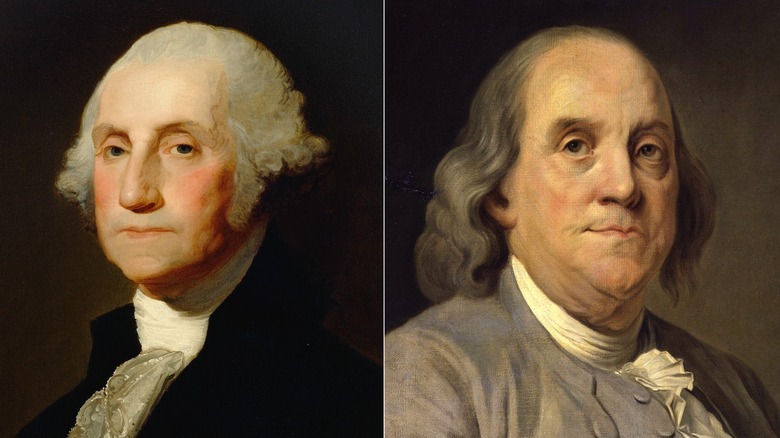

The Boston Tea Party provoked quite disparate reactions among the future leaders of the Revolution. John Adams of Massachusetts wrote an enthusiastic endorsement of it in his diary (via the American Battlefield Trust) — "the most magnificent movement of all," he called it. But in Virginia, George Washington's private correspondence (via the National Archives) shows a slightly more critical attitude, one that may have evolved in the lead-up to the revolution.

George Washington and other Founders supported Boston (but not the Tea Party)

George Washington's letter, addressed to George William Fairfax, was not a blanket condemnation of the Boston Tea Party. Written a year after the fact, he addressed the harsh measures imposed by Britain in response to the riot and declared that "the cause of Boston ... now is and ever will be considered as the cause of America," at least when it came to the response to such measures. He did, however, make his feelings on the specific act behind the Tea Party clear in a parenthetical aside: "not that we approve [the Bostonians'] conduct in destroying the tea."

If unambiguous, Washington's sentiments represent a mild rebuke. More critical was Benjamin Franklin of Philadelphia. Per the Boston Tea Party Ships & Museum, Franklin was considered a moderate until well into the conflict between Britain and its colonies, and even in 1773, he sought a nonviolent resolution. Writing from London, where he was acting as a representative of Pennsylvania (per Mount Vernon), Franklin told Samuel Adams and John Hancock that the East India Company, whose tea was destroyed, was not the colonists' enemy and that reparations should be paid for the damaged tea.

Even in his criticisms, Franklin meant to support his homeland. And after a humiliating appearance before the British privy council in the wake of the Tea Party (per The Benjamin Franklin Tercentenary), his moderation fell away. He returned to America and became a leading figure in the move toward independence.

The Founders believed that private property was sacrosanct

According to Harlow G. Unger's "American Tempest: How the Boston Tea Party Sparked a Revolution," George Washington's private feelings immediately after the Boston Tea Party may have been more intense than he later expressed to George William Fairfax. Unger claims that Washington considered the Bostonians behind the protest "mad," guilty of an unconscionable attack on private property, and he was of the same mind as Benjamin Franklin in thinking that the East India Company deserved to be compensated. This more critical stance of Washington's was played up by historical reenactors in Williamsburg in 2010 when the 21st-century political movement that appropriated the Tea Party name put questions about the event to the man playing Washington (per The Washington Post).

His private correspondence the year after the event suggests an evolution in Washington's views, but his and Franklin's criticism of the Tea Party — a point of contention for many of its critics — stemmed from their feelings on the value of private property. Apart from the material cost (the ruined tea came to between $1 and 2.5 million in today's currency according to the New England Historical Society) Washington and other American founders viewed property as an essential right.

Per the Pacific Legal Foundation, Washington considered property rights inseparable from the notion of personal liberty; per the University of Chicago, Franklin felt it was a "natural right" for a man to have enough private property to sustain himself. The threat posed to private property by protests or riots like the Boston Tea Party was unpalatable to such men — at least, until the British responded as they did.